“Out of Many, One:”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin

TEACHER WORKSHEET CYCLE 3 / 10–11 YR • HISTORY AND ART HISTORY THE 1936 OLYMPIC GAMES IN BERLIN OVERVIEW EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES: • Art history: • Remember that after World War I, peace in Relate characteristics of a work of art to usage Europe remained fragile. and to the historical and cultural context in which it was created. • Understand that Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party, which came to power legally in 1933, was racist and had plans to dominate the world. INTERDISCIPLINARY SKILLS: • Understand that by hosting the 1936 Olympic • Geography: Games in Berlin, the Nazi Party sought to Determine one’s place in space. demonstrate the superiority of the German race • Moral and civic education: and used the event as a means of propaganda. Understand the principles and values of a • Understand that the victories of Jesse Owens, democratic society. an African-American athlete, helped to disprove Nazi propaganda. SCHEDULE FOR SESSIONS: • Understand the values of the Olympic Games: • Launch project. encourage physical activity and the brotherhood • Gather initial student project feedback. of peoples, rejecting all forms of discrimination. • Read documents aloud as a class. • Familiarize oneself with a few Olympic athletics • Do three reading-comprehension activities in disciplines. pairs (text and image). • Share with class and review. ANNUAL PROGRAM GUIDELINES: • Extend activity. Topic 3: Two world wars in the 20th century DURATION: The Olympic Games under Hitler’s Germany in the pre-war period. • 2 sessions (2 × 45 minutes). ORGANIZATION: SPECIFIC SKILLS: • Work in pairs, then share as a class. • History: Determine one’s place in time: develop historical points of reference. -

Handbook of Sports and Media

Job #: 106671 Author Name: Raney Title of Book: Handbook of Sports & Media ISBN #: 9780805851892 HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA LEA’S COMMUNICATION SERIES Jennings Bryant/Dolf Zillmann, General Editors Selected titles in Communication Theory and Methodology subseries (Jennings Bryant, series advisor) include: Berger • Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action Dennis/Wartella • American Communication Research: The Remembered History Greene • Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory Hayes • Statistical Methods for Communication Science Heath/Bryant • Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges, Second Edition Riffe/Lacy/Fico • Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Second Edition Salwen/Stacks • An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA Edited by Arthur A.Raney College of Communication Florida State University Jennings Bryant College of Communication & Information Sciences The University of Alabama LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS Senior Acquisitions Editor: Linda Bathgate Assistant Editor: Karin Wittig Bates Cover Design: Tomai Maridou Photo Credit: Mike Conway © 2006 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. Copyright © 2006 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of sports and media/edited by Arthur A.Raney, Jennings Bryant. p. cm.–(LEA’s communication series) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Olympic Rowing Regatta Beijing, China 9-17 August

2008 Olympic Rowing Regatta Beijing, China 9-17 August MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTEnts 1. Introduction 3 2. FISA 5 2.1. What is FISA? 5 2.2. FISA contacts 6 3. Rowing at the Olympics 7 3.1. History 7 3.2. Olympic boat classes 7 3.3. How to Row 9 3.4. A Short Glossary of Rowing Terms 10 3.5. Key Rowing References 11 4. Olympic Rowing Regatta 2008 13 4.1. Olympic Qualified Boats 13 4.2. Olympic Competition Description 14 5. Athletes 16 5.1. Top 10 16 5.2. Olympic Profiles 18 6. Historical Results: Olympic Games 27 6.1. Olympic Games 1900-2004 27 7. Historical Results: World Rowing Championships 38 7.1. World Rowing Championships 2001-2003, 2005-2007 (current Olympic boat classes) 38 8. Historical Results: Rowing World Cup Results 2005-2008 44 8.1. Current Olympic boat classes 44 9. Statistics 54 9.1. Olympic Games 54 9.1.1. All Time NOC Medal Table 54 9.1.2. All Time Olympic Multi Medallists 55 9.1.3. All Time NOC Medal Table per event (current Olympic boat classes only) 58 9.2. World Rowing Championships 63 9.2.1. All Time NF Medal Table 63 9.2.2. All Time NF Medal Table per event 64 9.3. Rowing World Cup 2005-2008 70 9.3.1. Rowing World Cup Medal Tables per year 2005-2008 70 9.3.2. All Time Rowing World Cup Medal Tables per event 2005-2008 (current Olympic boat classes) 72 9.4. -

The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2016 The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W. Cody Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the European History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cody, Nathan W., "The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany" (2016). Student Publications. 434. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/434 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 434 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Abstract The aN zis utilized the Berlin Olympics of 1936 as anti-Semitic propaganda within their racial ideology. When the Nazis took power in 1933 they immediately sought to coordinate all aspects of German life, including sports. The process of coordination was designed to Aryanize sport by excluding non-Aryans and promoting sport as a means to prepare for military training. The 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin became the ideal platform for Hitler and the Nazis to display the physical superiority of the Aryan race. However, the exclusion of non-Aryans prompted a boycott debate that threatened Berlin’s position as host. -

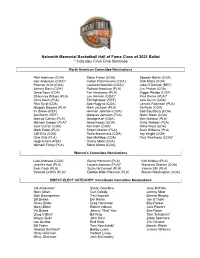

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

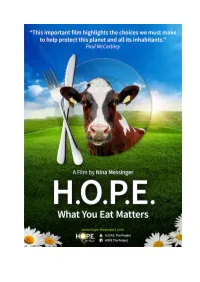

HOPE PRESSKIT.Pdf

H.O.P.E. What You Eat Matters A Film by Nina Messinger Documentary. Austria 2017. Running Time: 92 minutes. Language: English (with subtitles). Frame Rate: 25 fps. Shooting Format: HD. Sound: Dolby Digital 5.1, Stereo 2.0. www.hope-theproject.com H.O.P.E. What You Eat Matters I Press Kit SYNOPSIS (short) Obesity, allergies, diabetes, heart disease, or cancer: More than half of all people living in the industrialized world suffer from chronic diseases. Animals are reared for our consumption under abysmal conditions. Industrial-size livestock breeding facilities contribute to world hunger and the destruction of our natural environment and climate. The documentary H.O.P.E. shows how simply changing what we put on our plates and moving towards a plant-based diet can restore our body´s health and our planet´s balance. It has a clear message: By changing our eating habits, we can change the world! (long) Half of the population in Western society suffers from being overweight. Cardio- vascular diseases, diabetes and cancer are epidemic. Our meat consumption has quintupled over the past 50 years. 65 billion land animals are being slaughtered every year for food consumption. One third of the global grain production is fed to animals for fattening while 1.8 billion people worldwide suffer from hunger and starvation. Can there really be a solution to all these problems? It was the search for an answer to this question that led Austrian author and filmmaker Nina Messinger on a journey through Europe, India and the US to investigate the consequences of our diet and to meet with leading experts in nutrition, medicine, science, and agriculture, as well as with farmers and people who have recovered from severe illnesses by simply changing their eating habits. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 117 230 Relating to Racism, Blacks

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 117 230 ID015 623 TITLE A Selected Annotated Bibliography of .Material Relating to Racism, Blacks, Chicanos, Native Americans and Multi-Ethnicity. Vol-. 2. INSTITUTION Michigan Education Association, East Lansing. iv.'of Minority Affairs. PUB DATE 73 , NOTE 105p.; For volumes 1, 3, and 4; see ED 069 445, VD 015 624 and UD 015 718 respectively EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$5.70 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; *American Indians; *Annotated Bibliographies; Cultural Background; Cultural Factors; Ethnic'Groups; Ethnic Origins;, Ethnic Status Films; .Filmstrips; Instructional MaterialsC*Mexican Americans; *Negroes; Negro fiistory; Race'Relations; Racial Discrimination; Racial Factors; *Racism; Tape Recordings IDENTIFIERS Third World ABSTRACT The' second in the series, this selected annotated hihliography deals with new and recently discovered materials that address racism, BlackS, Chicanos,'native Americans, and multi - ethnicity. This bibliography is considered to be not all . inclusive but to reflect only on that material which,is considered to be most representative of the realities that relate to the involvemeiA and contributions of Third World groupS in'the development of the United States, and the climate of the times during which such involvement and contributions ocdurred.,Listing of materials usable at the elementary level are increased over those in Volume I. Contents deal with racism, including printed.materials, film, filmstrips, records and tapes; Black materials, including printed matter, films and filmstrips; Latino materials, including printed matter, films and filmstrips; native American materials, k. including printed matter, films and filmstrips; 'and multi-ethnic printed material. A list of Third World publishers is included. , (Author/AM) ********************************************************************* Documents acquired by ERIC include,many .informal Unpublished * materials not available from other sources. -

International Olympic Committee, Lausanne, Switzerland

A PROJECT OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE, LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND. WWW.OLYMPIC.ORG TEACHING VALUESVALUES AN OLYYMPICMPIC EDUCATIONEDUCATION TOOLKITTOOLKIT WWW.OLYMPIC.ORG D R O W E R O F D N A S T N E T N O C TEACHING VALUES AN OLYMPIC EDUCATION TOOLKIT A PROJECT OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE, LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The International Olympic Committee wishes to thank the following individuals for their contributions to the preparation of this toolkit: Author/Editor: Deanna L. BINDER (PhD), University of Alberta, Canada Helen BROWNLEE, IOC Commission for Culture & Olympic Education, Australia Anne CHEVALLEY, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Charmaine CROOKS, Olympian, Canada Clement O. FASAN, University of Lagos, Nigeria Yangsheng GUO (PhD), Nagoya University of Commerce and Business, Japan Sheila HALL, Emily Carr Institute of Art, Design & Media, Canada Edward KENSINGTON, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Ioanna MASTORA, Foundation of Olympic and Sport Education, Greece Miquel de MORAGAS, Centre d’Estudis Olympics (CEO) Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), Spain Roland NAUL, Willibald Gebhardt Institute & University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany Khanh NGUYEN, IOC Photo Archives, Switzerland Jan PATERSON, British Olympic Foundation, United Kingdom Tommy SITHOLE, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Margaret TALBOT, United Kingdom Association of Physical Education, United Kingdom IOC Commission for Culture & Olympic Education For Permission to use previously published or copyrighted -

Spitting in the Soup Mark Johnson

SPITTING IN THE SOUP INSIDE THE DIRTY GAME OF DOPING IN SPORTS MARK JOHNSON Copyright © 2016 by Mark Johnson All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100 Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA (303) 440-0601 · Fax (303) 444-6788 · E-mail [email protected] Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-1-937715-27-4 For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210, ext. 2138, or visit www.velopress.com. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Art direction by Vicki Hopewell Cover: design by Andy Omel; concept by Mike Reisel; illustration by Jean-Francois Podevin Text set in Gotham and Melior 16 17 18 / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Introduction ...................................... 1 1 The Origins of Doping ............................ 7 2 Pierre de Coubertin and the Fair-Play Myth ...... 27 3 The Fall of Coubertin’s Ideal ..................... 41 4 The Hot Roman Day When Doping Became Bad ..................................... 55 5 Doping Becomes a Crime........................ 75 6 The Birth of the World Anti-Doping Agency ..... 85 7 Doping and the Cold War........................ 97 8 Anabolic Steroids: Sports as Sputnik .......... -

Suburbanization Historic Context and Survey Methodology

INTRODUCTION The geographical area for this project is Maryland’s 42-mile section of the I-95/I- 495 Capital Beltway. The historic context was developed for applicability in the broad area encompassed within the Beltway. The survey of historic resources was applied to a more limited corridor along I-495, where resources abutting the Beltway ranged from neighborhoods of simple Cape Cods to large-scale Colonial Revival neighborhoods. The process of preparing this Suburbanization Context consisted of: • conducting an initial reconnaissance survey to establish the extant resources in the project area; • developing a history of suburbanization, including a study of community design in the suburbs and building patterns within them; • defining and delineating anticipated suburban property types; • developing a framework for evaluating their significance; • proposing a survey methodology tailored to these property types; • and conducting a survey and National Register evaluation of resources within the limited corridor along I-495. The historic context was planned and executed according to the following goals: • to briefly cover the trends which influenced suburbanization throughout the United States and to illustrate examples which highlight the trends; • to present more detail in statewide trends, which focused on Baltimore as the primary area of earliest and typical suburban growth within the state; • and, to focus at a more detailed level on the local suburbanization development trends in the Washington, D.C. suburbs, particularly the Maryland counties of Montgomery and Prince George’s. Although related to transportation routes such as railroad lines, trolley lines, and highways and freeways, the location and layout of Washington’s suburbs were influenced by the special nature of the Capital city and its dependence on a growing bureaucracy and not the typical urban industrial base. -

HUSKY OLYMPIANS Washington Rowers Have Been a Fixture in Olympic Competition, Dating Back to the 1936 Men’S Eight-Oared Boat That Won the Gold Medal in Berlin

HUSKY OLYMPIANS Washington rowers have been a fixture in Olympic competition, dating back to the 1936 men’s eight-oared boat that won the gold medal in Berlin. Altogether, Washington Men Husky men and women have participated in 10 Olympic Games. in the Olympics Washington was represented in the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games by former Huskies Marc Schneider, Jason Scott, Roberto Blanda, Hana Dariusova and Gordon Adam 1936 eight, Gold medal current Husky Sabina Telenska. Schneider was a part of the lightweight four Roberto Blanda 1992,96 eight (Italy) (without coxswain) that won the bronze medal. Scott also rowed in a four without Charles Day 1936 eight, Gold medal a coxswain and Blanda represented Italy in the men’s eight. Al Forney 1984 four, silver medal Telenska rowed for the Czech Republic as a part of the women’s eight in 1992 Gordon Giovanelli 1948 four, Gold medal and as a coxless pair, with Dariusova, in 1996. Husky coach Bob Ernst worked Blair Horn 1984 eight (Canada), gold medal the Olympic Games as a commentator for NBC Television. Jan Harville served Donald Hume 1936 eight, Gold medal as the coach of the U.S. Women’s Quad while Eleanor McElvaine was manager George Hunt 1936 eight, Gold medal of water activities at the rowing venue. Ed Ives 1984 four, silver medal Phil Leanderson 1952 four, Bronze medal Carl Lovsted 1952 four, Bronze medal James McMillin 1936 eight, Gold medal Robert Martin 1948 four, Gold medal Robert Moch 1936 eight, Gold medal Allen Morgan 1948 four, Gold medal Herbert Morris 1936 eight, Gold medal Scott Munn 1992 eight Joseph Rantz 1936 eight, Gold medal Albert Rossi 1952 four, Bronze medal Chad Rudolph 1972 four Charles Ruthford 1972 four John Sayre 1960 four without coxswain, Gold medal Marc Schneider 1996 lightweight four w/o coxswain, Bronze Jason Scott 1996 four without coxswain Robert Shepard 1992 eight Alvin Ulbrickson, Jr. -

Caldwell Esselstyn, M.D

Experts to Follow Caldwell Esselstyn, M.D. ʺDr. Esselstyn is a physician, author and former Olympic rowing champion. He is the author of Prevent and Reverse Heart Disease in which he demonstrates the benefits of a whole- foods, plant-based diet.ʺ To learn more about Dr. Esselstynʹs amazing work visit his website at http://www.dresselstyn.com/ Caldwell B. Esselstyn, Jr., received his B.A. from Yale University and his M.D. from Western Reserve University. In 1956, pulling the No. 6 oar as a member of the victorious United States rowing team, he was awarded a gold medal at the Olympic Games. He was trained as a surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic and at St. Georgeʹs Hospital in London. In 1968, as an Army surgeon in Vietnam, he was awarded the Bronze Star. Dr. Esselstyn has been associated with the Cleveland Clinic since 1968. During that time, he has served as President of the Staff and as a member of the Board of Governors. He chaired the Clinicʹs Breast Cancer Task Force and headed its Section of Thyroid and Parathyroid Surgery. He is a Fellow of the American College of Cardiology. Website: https://www.pbhw.com 1 Email: [email protected] In 1991, Dr. Esselstyn served as President of the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons. That same year he organized the first National Conference on the Elimination of Coronary Artery Disease, which was held in Tucson, Arizona. In 1997, he chaired a follow-up conference, the Summit on Cholesterol and Coronary Disease, which brought together more than 500 physicians and health-care workers in Lake Buena Vista, Florida.