Spitting in the Soup Mark Johnson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Titel Interpret

Titel Interpret 15 MILJOEN MENSEN FLUITSMA & VAN THIJN 1948 GERARD COX 24 ROZEN TOON HERMANS AAN DIE AMSTERDAMSE GRACHTEN WIM ZONNEVELD AAN DE KUST BLOF ADEM MIJN ADEM PETER SSHAAP ADEMNOOD LINDA, ROOS & JESSICA ALLE DUIVEN OP DE DAM GERT & HERMIEN ALS STERREN STRALEN MARIANNE WEBER ANNABEL HANS DE BOOIJ ANNE HERMAN VAN VEEN ANTON AUS TIROL DE ZWARE JONGENS BANGER HART ROB DE NIJS BEESTJES RONNIE EN DE RONNIES BEN IK TE MIN ARMAND BIG CITY TOL HANSEN BIJ ONS STAAT OP DE KEUKENDEUR DE TWEE PINTEN BIJNA EDDY ZOEY BINNEN MARCO BORSATO BLIJF BIJ MIJ RUTH JACOTT BRABANTSE NACHTEN ZIJN LANG ARIE RIBBENS COMMENT CA VA THE SHORTS DAAR GAAT ZE CLOUSEAU DANS JE DE HELE NACHT MET MIJ DE JONNIES DAT AFGEZAAGDE ZINNETJE WILLY & WILLEKE ALBERTI DE BOM DOE MAAR DE CLOWN BEN CRAMER DE HEILSOLDAAT ZANGERES ZONDER NAAM ROZEN NAAR SANDRA RONNY TOBER DE NOZEM EN DE NON CORNELIS VREESWIJK DE OUDE MUZIKANT VADER ABRAHAM DE REGENBOOG FRANS BAUER & MARIANNE WEBER DE TWEE MOTTEN DORUS DE VEERPONT DRS. P DE VERZONKEN STAD FRANK & MIRELLA DE WAARHEID MARCO BORSATO DE WANDELCLUB SUGAR LEE HOOPER DE WILDE BOERNDOCHTERE IVAN HEYLEN DE ZEE TRIJNTJE OOSTERHUIS DIE LAAIELICHTER GERARD COX DIKKERTJE DAP HERMAN VAN VEEN DODENRIT DRS. P DROMEN ZIJN BEDROG MARCO BORSATO EEN PIKKETANUSSIE JOHNNY JORDAAN EEN ROOSJE M'N ROOSJE CONNY VANDENBOS FREKIE JOOST PRINSEN GEEF M'N HOOP JOMANDA GIJP GEWOON EEN VROLIJK LIEDJE DENNIS GOEDE TIJDEN SLECHTE TIJDEN LISA BORAY GROETEN UIT MAAIVELD ACDA & DE MUNNIK GUUS ALEXANDER CURLY HEB JE EVEN VOOR MIJ FRANS BAUER HET DORP WIM SONNEVELD -

Armstrong.Pdf

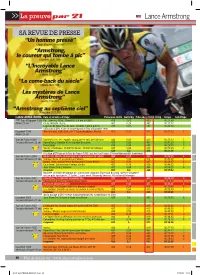

>> La preuve par 21 Lance Armstrong SA REVUE DE PRESSE “Un homme pressé” L’Equipe Magazine, 04.09.1993 “Armstrong, le coureur qui tombe à pic” L’Humanité, 05.07.1999 “L’Incroyable Lance Armstrong” L’Equipe, 12.07.1999 “Le come-back du siècle” L’Equipe, 26.07.1999 “Les mystères de Lance Armstrong” Le JDD, 27.06.2004 “Armstrong au septième ciel” Le Midi Libre, 25.07.2005 Lance ARMSTRONG Cols et victoires d’étape Puissance réelle watts/kg Puissance étalon 78 kg temps Cols Etape Tour Tour d’Espagne 1998 Pal. Jimenez 433w, 20min30s, 8,4 km à 6,49%, 418 5,65 400 00:21:49 4ème-27 ans Cerler. Montée courte. 462 6,24 442 00:11:33 Lagunas de Neila. Peu de vent, en forêt, 7 km à 8,57%, 415 5,61 397 00:22:18 Utilisation d’EPO et de cortisone durant le Tour d’Espagne 1998 Dauphiné 1999 Mont Ventoux CLM. ‘Battu de 1’1s par Vaughters. Record. 455 6,15 432 00:57:52 1 8ème-28 ans Tour de France 2004 La Mongie. 2ème derrière Basso 487 6,58 462 00:23:15 2 Tour de France 1999 Sestrières 1er. 1er «exploit» marquant en solo. Vent de face 448 6,05 420 00:27:13 5 1er puis déclassé-33 ans Beille 1er. En solitaire. 438 5,92 416 00:45:40 6 1er puis déclassé-28 ans Alpe d’Huez. Contrôle et se contente de suivre. 436 5,89 407 00:41:20 3 Chalimont 1er. Victoire à Villard de Lans 410 5,54 392 00:19:05 3 Piau Engaly 395 5,34 385 00:26:15 5 Alpe d’Huez CLM 1er. -

G on Page 6- ‘ MANCHESTER, CONK., FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 4V 1927: Riisasn' PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS

VOL. XLI., NO. 107. Classified AdTertising on Page 6- ‘ MANCHESTER, CONK., FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 4v 1927: riisaSN' PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS THIS PADLOCK NO Bury Politics in Exploration B O J m WORK BOOZE,BARRIER FIGHTINGPLANS Protected from Cops 2 Boys GROWS: GIVES Who Passed Hooch Through OUST ECONOMY Hole in Floor. ' TOWNraOBLQi New Britain Feb. 4.— John A T W « G T 0 N Smi'gel, 42, of 24 Orange street, was found guilty in po lice court today bn two counts Retirement of All Selectmen of liquor law violations. Ac Administration Quits Its cording to the police who raid-, FREAKISH BIG GALE U. 5 . Pact. ed his home last night, when - - I Next Year Would Serious the officers tried to enter the Fight With Preparedness cellar of Smigel’g home they ROUGH IN PRANKS For Defense is Reported found the door of the cellar Men in Congress on Army ly Handicap Town; Likely padlocked and an iron bar <?> placed to block their entrance. Candidates Sought. The police sent to a fire de and Marine Corps. DOING TALES TO partment station, procured Bombards New Haven Train, Fang, Defender o f Shanghai crowbars and broke the door PAY 3 MILLION Wlietlier or not Manchester has down. In the cellar they found Washington, Feb. 4.— ^Virtually Plays Hob at Boston and Against Cantonese, SaU outgiown its present form of gov two young sons of Smigel nine Young Vanderbilt Says He abandoning its fight with the pre ernment -will be thoroughly tested and twelve, whose duties were Will Settle Up If it Takes during the next year when the reins to hand up the liquor as fast paredness bloc in Congress, the-ad Elsewhere. -

Lance Armstrong Has Something to Get Off His Chest

Texas Monthly July 2001: Lanr^ Armstrong Has Something to . Page 1 of 17 This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. For public distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, contact [email protected] for reprint information and fees. (EJiiPfflNITHIS Lance Armstrong Has Something to Get Off His Chest He doesn't use performance-enhancing drugs, he insists, no matter what his critics in the European press and elsewhere say. And yet the accusations keep coming. How much scrutiny can the two-time Tour de France winner stand? by Michael Hall In May of last year, Lance Armstrong was riding in the Pyrenees, preparing for the upcoming Tour de France. He had just completed the seven-and-a-half-mile ride up Hautacam, a treacherous mountain that rises 4,978 feet above the French countryside. It was 36 degrees and raining, and his team's director, Johan Bruyneel, was waiting with a jacket and a ride back to the training camp. But Lance wasn't ready to go. "It was one of those moments in my life I'll never forget," he told me. "Just the two of us. I said, 'You know what, I don't think I got it. I don't understand it.1 Johan said, 'What do you mean? Of course you got it. Let's go.' I said, 'No, I'm gonna ride all the way down, and I'm gonna do it again.' He was speechless. And I did it again." Lance got it; he understood Hautacam—in a way that would soon become very clear. -

Radio 2 Paradeplaat Last Change Artiest: Titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley

Radio 2 Paradeplaat last change artiest: titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley Moody Blue 10 2 David Dundas Jeans On 15 3 Chicago Wishing You Were Here 13 4 Julie Covington Don't Cry For Me Argentina 1 5 Abba Knowing Me Knowing You 2 6 Gerard Lenorman Voici Les Cles 51 7 Mary MacGregor Torn Between Two Lovers 11 8 Rockaway Boulevard Boogie Man 10 9 Gary Glitter It Takes All Night Long 19 10 Paul Nicholas If You Were The Only Girl In The World 51 11 Racing Cars They Shoot Horses Don't they 21 12 Mr. Big Romeo 24 13 Dream Express A Million In 1,2,3, 51 14 Stevie Wonder Sir Duke 19 15 Champagne Oh Me Oh My Goodbye 2 16 10CC Good Morning Judge 12 17 Glen Campbell Southern Nights 15 18 Andrew Gold Lonely Boy 28 43 Carly Simon Nobody Does It Better 51 44 Patsy Gallant From New York to L.A. 15 45 Frankie Miller Be Good To Yourself 51 46 Mistral Jamie 7 47 Steve Miller Band Swingtown 51 48 Sheila & Black Devotion Singin' In the Rain 4 49 Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers Egyptian Reggae 2 1978 11 Chaplin Band Let's Have A Party 19 1979 47 Paul McCartney Wonderful Christmas time 16 1984 24 Fox the Fox Precious little diamond 11 52 Stevie Wonder Don't drive drunk 20 1993 24 Stef Bos & Johannes Kerkorrel Awuwa 51 25 Michael Jackson Will you be there 3 26 The Jungle Book Groove The Jungle Book Groove 51 27 Juan Luis Guerra Frio, frio 51 28 Bis Angeline 51 31 Gloria Estefan Mi tierra 27 32 Mariah Carey Dreamlover 9 33 Willeke Alberti Het wijnfeest 24 34 Gordon t Is zo weer voorbij 15 35 Oleta Adams Window of hope 13 36 BZN Desanya 15 37 Aretha Franklin Like -

Handbook of Sports and Media

Job #: 106671 Author Name: Raney Title of Book: Handbook of Sports & Media ISBN #: 9780805851892 HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA LEA’S COMMUNICATION SERIES Jennings Bryant/Dolf Zillmann, General Editors Selected titles in Communication Theory and Methodology subseries (Jennings Bryant, series advisor) include: Berger • Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action Dennis/Wartella • American Communication Research: The Remembered History Greene • Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory Hayes • Statistical Methods for Communication Science Heath/Bryant • Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges, Second Edition Riffe/Lacy/Fico • Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Second Edition Salwen/Stacks • An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA Edited by Arthur A.Raney College of Communication Florida State University Jennings Bryant College of Communication & Information Sciences The University of Alabama LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS Senior Acquisitions Editor: Linda Bathgate Assistant Editor: Karin Wittig Bates Cover Design: Tomai Maridou Photo Credit: Mike Conway © 2006 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. Copyright © 2006 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of sports and media/edited by Arthur A.Raney, Jennings Bryant. p. cm.–(LEA’s communication series) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

How to Maximize Your Baseball Practices

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the author. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ii DEDICATED TO ••• All baseball coaches and players who have an interest in teaching and learning this great game. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to\ thank the following individuals who have made significant contributions to this Playbook. Luis Brande, Bo Carter, Mark Johnson, Straton Karatassos, Pat McMahon, Charles Scoggins and David Yukelson. Along with those who have made a contribution to this Playbook, I can never forget all the coaches and players I have had the pleasure tf;> work with in my coaching career who indirectly have made the biggest contribution in providing me with the incentive tQ put this Playbook together. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS BASEBALL POLICIES AND REGULATIONS ......................................................... 1 FIRST MEETING ............................................................................... 5 PLAYER INFORMATION SHEET .................................................................. 6 CLASS SCHEDULE SHEET ...................................................................... 7 BASEBALL SIGNS ............................................................................. 8 Receiving signs from the coach . 9 Sacrifice bunt. 9 Drag bunt . 10 Squeeze bunt. 11 Fake bunt and slash . 11 Fake bunt slash hit and run . 11 Take........................................................................................ 12 Steal ....................................................................................... -

FROM BULLDOGS to SUN DEVILS the EARLY YEARS ASU BASEBALL 1907-1958 Year ...Record

THE TRADITION CONTINUES ASUBASEBALL 2005 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 2 There comes a time in a little boy’s life when baseball is introduced to him. Thus begins the long journey for those meant to play the game at a higher level, for those who love the game so much they strive to be a part of its history. Sun Devil Baseball! NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONS: 1965, 1967, 1969, 1977, 1981 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 3 ASU AND THE GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD > For the past 26 years, USA Baseball has honored the top amateur baseball player in the country with the Golden Spikes Award. (See winners box.) The award is presented each year to the player who exhibits exceptional athletic ability and exemplary sportsmanship. Past winners of this prestigious award include current Major League Baseball stars J. D. Drew, Pat Burrell, Jason Varitek, Jason Jennings and Mark Prior. > Arizona State’s Bob Horner won the inaugural award in 1978 after hitting .412 with 20 doubles and 25 RBI. Oddibe McDowell (1984) and Mike Kelly (1991) also won the award. > Dustin Pedroia was named one of five finalists for the 2004 Golden Spikes Award. He became the seventh all-time final- ist from ASU, including Horner (1978), McDowell (1984), Kelly (1990), Kelly (1991), Paul Lo Duca (1993) and Jacob Cruz (1994). ODDIBE MCDOWELL > With three Golden Spikes winners, ASU ranks tied for first with Florida State and Cal State Fullerton as the schools with the most players to have earned college baseball’s top honor. BOB HORNER GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD WINNERS 2004 Jered Weaver Long Beach State 2003 Rickie Weeks Southern 2002 Khalil Greene Clemson 2001 Mark Prior Southern California 2000 Kip Bouknight South Carolina 1999 Jason Jennings Baylor 1998 Pat Burrell Miami 1997 J.D. -

Juniors Hommes

CHAMPIONNATS DU MONDE ROUTE UCI 16 au 24 septembre 2017 DOSSIER DE PRESSE Bergen, NORVEGE BERGEN (NORVEGE) Bergen est une ville du Sud-Ouest de la Norvège, capitale du comté de Hordaland. Elle est la deuxième ville du pays avec ses 280’000 habitants. C’est une cité internationale possédant le charme et l’atmosphère d’un petit village. “Porte d’entrée des Fjords de Norvège”, Bergen est classée patrimoine mondial par l’UNESCO et a le statut de Ville Européenne de la Culture. La côte de la région de Bergen est parsemée de milliers de petites îles. L’archipel et les majestueux fjords forment un paysage très varié. La ville est comme un spectaculaire amphithéâtre grimpant sur les flancs de la montagne, surplombant la mer et entourant ses visiteurs. La tradition et l’histoire se côtoient avec une scène culturelle très dynamique. L’héritage de la période hanséatique va de pair avec le statut actuel de Bergen comme Ville Européenne de la Culture. Les deux sont très visibles lorsqu’on se promène dans la ville. Bergen est protégée de la Mer du Nord par les îles Askøy, Holsnøy (la municipalité de Meland) et Sotra (les municipalités de Fjell, Sund et Øygarden). De par sa proximité avec la Mer du Nord et les Fjords, Bergen et sa région sont habituées à des conditions climatiques variées. Du ciel bleu clair à la joie de la pluie, les habitants de l’Ouest de la Norvège vivent avec la nature. Grâce au Gulf Stream (“courant du golfe”), le climat est bien meilleur que la latitude ne l’indique. -

The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2016 The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W. Cody Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the European History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cody, Nathan W., "The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany" (2016). Student Publications. 434. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/434 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 434 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Abstract The aN zis utilized the Berlin Olympics of 1936 as anti-Semitic propaganda within their racial ideology. When the Nazis took power in 1933 they immediately sought to coordinate all aspects of German life, including sports. The process of coordination was designed to Aryanize sport by excluding non-Aryans and promoting sport as a means to prepare for military training. The 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin became the ideal platform for Hitler and the Nazis to display the physical superiority of the Aryan race. However, the exclusion of non-Aryans prompted a boycott debate that threatened Berlin’s position as host. -

1 Soulsister the Way to Your Heart 1988 2 Two Man Sound Disco

1 Soulsister The Way To Your Heart 1988 2 Two Man Sound Disco Samba 1986 3 Clouseau Daar Gaat Ze 1990 4 Isabelle A He Lekker Beest 1990 5 Katrina & The Waves Walking On Sunshine 1985 6 Blof & Geike Arnaert Zoutelande 2017 7 Marianne Rosenberg Ich Bin Wie Du 1976 8 Kaoma Lambada 1989 9 George Baker Selection Paloma Blanca 1975 10 Helene Fischer Atemlos Durch Die Nacht 2014 11 Mavericks Dance The Night Away 1998 12 Elton John Nikita 1985 13 Vaya Con Dios Nah Neh Nah 1990 14 Dana Winner Westenwind 1995 15 Patrick Hernandez Born To Be Alive 1979 16 Roy Orbison You Got It 1989 17 Benny Neyman Waarom Fluister Ik Je Naam Nog 1985 18 Andre Hazes Jr. Leef 2015 19 Radio's She Goes Nana 1993 20 Will Tura Hemelsblauw 1994 21 Sandra Kim J'aime La Vie 1986 22 Linda De Suza Une Fille De Tous Les Pays 1982 23 Mixed Emotions You Want Love (Maria, Maria) 1987 24 John Spencer Een Meisje Voor Altijd 1984 25 A-Ha Take On Me 1985 26 Erik Van Neygen & Sanne Veel Te Mooi 1990 27 Al Bano & Romina Power Felicita 1982 28 Queen I Want To Break Free 1984 29 Adamo Vous Permettez Monsieur 1964 30 Frans Duijts Jij Denkt Maar Dat Je Alles Mag Van Mij 2008 31 Piet Veerman Sailin' Home 1987 32 Creedence Clearwater Revival Bad Moon Rising 1969 33 Andre Hazes Ik Meen 't 1985 34 Rob De Nijs Banger Hart 1996 35 VOF De Kunst Een Kopje Koffie 1987 36 Radio's I'm Into Folk 1989 37 Corry Konings Mooi Was Die Tijd 1990 38 Will Tura Mooi, 't Leven Is Mooi 1989 39 Nick MacKenzie Hello Good Morning 1980/1996 40 Noordkaap Ik Hou Van U 1995 41 F.R. -

Lorenzo Fabiano – Matteo Fontana IL DUELLO Absolutely Free Editore, 2017, Euro 15,00

Lorenzo Fabiano – Matteo Fontana IL DUELLO Absolutely Free Editore, 2017, euro 15,00 US Vicarello 1919 www.usv1919.it giugno 2021 L’episodio al centro di questo libro è ormai entrato nella leggenda del ciclismo: 10 giugno 1984, ultima tappa del Giro, cronometro da Soave a Verona. Laurent Fignon, maglia rosa, deve difendersi dall’ultimo attacco di Francesco Moser, secondo in classifica. Moser trionferà nella cronometro e vincerà il Giro d’Italia dopo tanti tentativi falliti. Ma il lavoro di Lorenzo Fabiano e Matteo Fontana, racconta molto di più che non la storia di quell’ormai mitico Giro: ricostruisce la storia ciclistica di Moser e Fignon ma ci fa rivivere anche il ciclismo degli anni ‘80 con le sue vicende e i suoi tanti protagonisti. FRANCESCO MOSER … Come si legge su Wikipedia: “Professionista dal 1973 al 1988, è stato soprannominato Lo Sceriffo per la capacità di gestire il gruppo durante la corsa; in carriera ha vinto un Giro d'Italia e diverse classiche, tra cui tre Parigi-Roubaix, due Giri di Lombardia, una Freccia Vallone, una Gand-Wevelgem e US Vicarello 1919 www.usv1919.it giugno 2021 una Milano-Sanremo, oltre ad un campionato del mondo su strada ed uno su pista nell'inseguimento individuale. Con 273 vittorie su strada da professionista risulta a tutt'oggi il ciclista italiano con il maggior numero di successi, precedendo Giuseppe Saronni (193) e Mario Cipollini (189); è inoltre terzo assoluto a livello mondiale alle spalle di Eddy Merckx (426) e Rik Van Looy (379) e davanti a Rik Van Steenbergen (270) e Roger De Vlaeminck (255).” Fabiano e Fontana ricordano questa enorme carriera ma concentrano la loro attenzione soprattutto sugli avvenimenti del 1983.