Housing in the Nation's Capital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

Government of the District of Columbia Advisory Neighborhood Commission 3B Glover Park and Cathedral Heights

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ADVISORY NEIGHBORHOOD COMMISSION 3B GLOVER PARK AND CATHEDRAL HEIGHTS ANC – 3B Minutes November 13, 2008 A quorum was established and the meeting was called to order at 7:05 p.m. The Chair asked if there were any changes to the agenda. Under New Business, liquor license renewal requests for Whole Foods and Glover Park Market were tabled as well as the administrative item on “Consideration of Proposed Changes to the ANC Grant Guidelines.” The agenda was modified, moved, properly seconded, and passed by unanimous consent. All Commissioners were present: 3B01 – Cathy Fiorillo 3B02 – Alan Blevins 3B01 – Melissa Lane 3B04 – Howie Kreitzman, absent 3B05 – Brian Cohen 2nd District Police Report Crime and Traffic Reports. Crime is slightly up over last year with the police blaming the economy. During October there were 42 thefts from autos, half of them were GPS’s. As always, police recommended that citizens lock their cars and do not leave anything out in plain view. Citizens should do the same with their homes and garages. There have been a number of thefts from garages when the home owner left their garage door open. Officer Bobby Finnel is being transferred into PSA 204 from the PSA that encompasses Friendship Heights. Officer Dave Baker gave the traffic report. Every month, Officer Baker plans to give a tip for citizens. This month he talked about license tags for non-traditional motor vehicles. Officer Baker distributed a tip sheet on this subject. Any motorcycle that has wheels less than 16” in diameter and a motorized bicycle that has wheels greater than 16” are required to register. -

ROUTES LINE NAME Sunday Supplemental Service Note 1A,B Wilson Blvd-Vienna Sunday 1C Fair Oaks-Fairfax Blvd Sunday 2A Washington

Sunday Supplemental ROUTES LINE NAME Note Service 1A,B Wilson Blvd-Vienna Sunday 1C Fair Oaks-Fairfax Blvd Sunday 2A Washington Blvd-Dunn Loring Sunday 2B Fair Oaks-Jermantown Rd Sunday 3A Annandale Rd Sunday 3T Pimmit Hills No Service 3Y Lee Highway-Farragut Square No Service 4A,B Pershing Drive-Arlington Boulevard Sunday 5A DC-Dulles Sunday 7A,F,Y Lincolnia-North Fairlington Sunday 7C,P Park Center-Pentagon No Service 7M Mark Center-Pentagon Weekday 7W Lincolnia-Pentagon No Service 8S,W,Z Foxchase-Seminary Valley No Service 10A,E,N Alexandria-Pentagon Sunday 10B Hunting Point-Ballston Sunday 11Y Mt Vernon Express No Service 15K Chain Bridge Road No Service 16A,C,E Columbia Pike Sunday 16G,H Columbia Pike-Pentagon City Sunday 16L Annandale-Skyline City-Pentagon No Service 16Y Columbia Pike-Farragut Square No Service 17B,M Kings Park No Service 17G,H,K,L Kings Park Express Saturday Supplemental 17G only 18G,H,J Orange Hunt No Service 18P Burke Centre Weekday 21A,D Landmark-Bren Mar Pk-Pentagon No Service 22A,C,F Barcroft-South Fairlington Sunday 23A,B,T McLean-Crystal City Sunday 25B Landmark-Ballston Sunday 26A Annandale-East Falls Church No Service 28A Leesburg Pike Sunday 28F,G Skyline City No Service 29C,G Annandale No Service 29K,N Alexandria-Fairfax Sunday 29W Braeburn Dr-Pentagon Express No Service 30N,30S Friendship Hghts-Southeast Sunday 31,33 Wisconsin Avenue Sunday 32,34,36 Pennsylvania Avenue Sunday 37 Wisconsin Avenue Limited No Service 38B Ballston-Farragut Square Sunday 39 Pennsylvania Avenue Limited No Service 42,43 Mount -

National China Garden Foundation

MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT AMONG THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICER, THE NATIONAL CAPITAL PLANNING COMMISSION, AND THE NATIONAL CHINA GARDEN FOUNDATION REGARDING THE NATIONAL CHINA GARDEN AT THE U.S. NATIONAL ARBORETUM, WASHINGTON, D.C. This Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) is made as of this 18th day of November 2016, by and among the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Agricultural Research Service (ARS), the District of Columbia State Historic Preservation Officer (DCSHPO), the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), and the National China Garden Foundation (NCGF), (referred to collectively herein as the “Parties” or “Signatories” or individually as a “Party” or “Signatory”) pursuant to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), 16 U.S.C. §470f and its implementing regulations 36 CFR Part 800, and Section 110 of the NHPA, 16 U.S.C. § 470h-2. WHEREAS, the United States National Arboretum (USNA) is a research and education institution, public garden and living museum, whose mission is to enhance the economic, environmental, and aesthetic value of landscape plants through long-term, multidisciplinary research, conservation of genetic resources, and interpretative gardens and educational exhibits. Established in 1927, and opened to the public in 1959, the USNA is the only federally-funded arboretum in the United States and is open to the public free of charge; and, WHEREAS, the USNA, located at 3501 New York Avenue, NE, is owned by the United States government and under the administrative jurisdiction of the USDA’s ARS and occupies approximately 446 acres in Northeast Washington, DC and bound by Bladensburg Road on the west, New York Avenue on the north, and M Street on the south. -

Sheridan-Kalorama Historical Association (“SKHA”)

Sheridan-Kalorama Historical Association, Inc. 2330 California St. NW Washington, D.C. 20008 January 19, 2018 Mr. Frederick L. Hill, Chairperson District of Columbia Board of Zoning Adjustment 441 4th Street NW Suite 210S Washington, DC 20001 RE: BZA # 19659 Zone District R-3 Square 2531 Lot 0049 2118 Leroy Place NW (the “Property”) Dear Chairperson Hill and Honorable Members of the Board: Sheridan-Kalorama Historical Association (“SKHA”) respectfully requests that the Board of Zoning Adjustment deny the variance and special exception relief requested by the applicant in the above-referenced case (the “Applicant”). If granted, the relief would permit the property at 2118 Leroy Place NW (the “Property”) to be used as offices for the Federation of State Medical Boards (“FSMB”). 1: Sheridan-Kalorama Historic District is a Residential Neighborhood. The Property is located within the Sheridan-Kalorama Historic District, which was created in 1989 (the “Historic District”) and “by the 1910s, the neighborhood was firmly established as an exclusive residential neighborhood.” See HPO’s brochure on the Historic District, attached here at Exhibit “A”.1 Further, the National Park Service Historic District Nomination, a copy of the relevant pages are attached here at Exhibit “B” establishes the Historic District’s “residential character”, stating in relevant part: Sheridan-Kalorama is comprised of a network of cohesive town-and suburb-like streetscapes. The streets are lined with a variety of housing forms, each of which contributes to the sophisticated residential image that is unique within Washington, DC. This distinctive area, a verdant residential enclave nestled in the midst of the city, contains a total of 608 primary buildings erected between 1890 and 1988. -

Appendices for the Maternal Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIEHCV) Needs Assessment for Washington DC September 2020

Appendices for the Maternal Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIEHCV) Needs Assessment for Washington DC September 2020 Prepared by: Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development Prepared for: District of Columbia Department of Health Child and Adolescent Health Division Child, Adolescent, School Health Bureau Community Health Administration 899 North Capitol Street, NE Washington, DC 20002 September 20, 2020 Copy for HRSA Review and Comment Only Do Not Disseminate Without Permission 1 Table of Contents for Appendices Appendix 1: Defining At-Risk Communities Appendix #1a………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 Appendix #1b………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Appendix #1c………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Appendix #1d……………………………………………………………………………………………………..…..7 Appendix #1e……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…8 Appendix #1f………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Appendix #1g…………………………………………………………………………………………………….….11 Appendix 2: Home Visiting Capacity Assessment Appendix #2a……………………………………………………………………………………………………….12 Appendix #2b……………………………………………………………………………………………………….18 Appendix #2c……………………………………………………………………………………………………….20 Appendix 3: SUD/MH Capacity Assessment Appendix #3a……………………………………………………………………………………………………….22 Appendix #3b………………………………………………………………………………………………….……26 Appendix #3c……………………………………………………………………………………………………….30 Appendix 4: Interim Findings from the American Community Survey …………………….…………..32 2 Appendix 1: Defining At-Risk Communities Appendix #1a: Original HRSA/UIC Domains and -

H/Benning Historic Architectural Survey

H Street/Benning Road Streetcar Project Historic Architectural Survey Prepared for: District Department of Transportation Prepared by: Jeanne Barnes HDR Engineering, Inc. 2600 Park Tower Drive Suite 100 Vienna, VA 22180 FINAL SUBMITTAL April 2013 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Project Background ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.1.1. Overhead Catenary System ................................................................................................... 2 1.1.2. Car Barn Training Center ....................................................................................................... 4 1.1.3. Traction Power Sub‐Stations ................................................................................................. 5 1.1.4. Interim Western Destination ................................................................................................ 6 1.2. Regulatory Context ....................................................................................................................... 7 1.2.1. DC Inventory of Historic Sites ............................................................................................... 7 1.2.2. National Register cof Histori Places ...................................................................................... 8 1.3. District of Columbia Preservation Process ................................................................................... -

DCPLUG ANC 3E Brief 4.11.19 FINAL

District of Columbia Power Line Undergrounding (DC PLUG) Initiative Presented to: ANC 3E Presented by: Anthony Soriano and Laisha Dougherty April 11, 2019 www.dcpluginfo.com Agenda • Background and History • Biennial Plan Feeder Locations • Feeder 308 Proposed Scope of Work • Customer Outreach • Contact Us 2 Background Background & Timeline Budget Aug 2012 Pepco Portion DC PLUG will provide resiliency The Mayor’s Power Line Undergrounding against major storms and improve the Task Force establishment $250 Million reliability of the electric system May 2013 * Recovered through Pepco The Task Force recommended Pepco and Underground Project Charge DDOTs partnership May 2014 District Portion The Electric Company Infrastructure $187.5 Million Improvement Financing Act became law Multi–year program to underground May 2017 * Recovered through Underground Rider up to 30 of the most vulnerable Council of the District of Columbia overhead distribution lines, spanning amended the law DDOT over 6-8 years with work beginning in July 2017 mid 2019 Pepco and DDOT filed a joint Biennial Plan up to $62.5 Million Nov 2017 DDOT Capital Improvement Funding Received Approval from D.C. Public Service Commission on the First Biennial Plan 3 Biennial Plan • In accordance with the Act, Pepco and DDOT filed a joint Biennial Plan on July 3, 2017 covering the two-year period, 2017-2019. The next Biennial Plan is planned to be filed September 2019. • Under the Biennial Plan, DDOT primarily will construct the underground facilities, and Pepco primarily will install -

Historic District Vision Faces Debate in Burleith

THE GEORGETOWN CURRENT Wednesday, June 22, 2016 Serving Burleith, Foxhall, Georgetown, Georgetown Reservoir & Glover Park Vol. XXV, No. 47 D.C. activists HERE’S LOOKING AT YOU, KID Historic district vision sound off on faces debate in Burleith constitution ciation with assistance from Kim ■ Preservation: Residents Williams of the D.C. Historic By CUNEYT DIL Preservation Office. The goal of Current Correspondent divided at recent meeting the presentation, citizens associa- By MARK LIEBERMAN tion members said, was to gather Hundreds of Washingtonians Current Staff Writer community sentiments and turned out for two constitutional address questions about the impli- convention events over the week- Burleith took a tentative step cations of an application. Many at end to give their say on how the toward historic district designa- the meeting appeared open to the District should function as a state, tion at a community meeting benefits of historic designation, completing the final round of pub- Thursday — but not everyone was while some grumbled that the pre- lic comment in the re-energized immediately won over by the sentation focused too narrowly on push for statehood. prospect. positive ramifications and not The conventions, intended to More than 40 residents of the enough on potential negative ones. hear out practical tweaks to a draft residential neighborhood, which Neighborhood feedback is cru- constitution released last month, lies north and west of George- cial to the process of becoming a brought passionate speeches, and town, turned out for a presentation historic district, Williams said dur- even songs, for the cause. The from the Burleith Citizens Asso- See Burleith/Page 2 events at Wilson High School in Tenleytown featured guest speak- ers and politicians calling on the city to seize recent momentum for Shelter site neighbors seek statehood. -

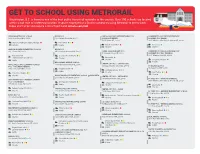

GET to SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C

GET TO SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C. is home to one of the best public transit rail networks in the country. Over 100 schools are located within a half mile of a Metrorail station. If you’re employed at a District school, try using Metrorail to get to work. Rides start at $2 and require a SmarTrip® card. wmata.com/rail AIDAN MONTESSORI SCHOOL BRIYA PCS CARLOS ROSARIO INTERNATIONAL PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 2700 27th Street NW, 20008 100 Gallatin Street NE, 20011 (SONIA GUTIERREZ) ACADEMY PCS (MAIN) 514 V Street NE, 20002 2405 Martin Luther King Jr Avenue SE, 20020 Woodley Park-Zoo Adams Morgan Fort Totten Private Charter Rhode Island Ave Anacostia Charter Charter AMIDON-BOWEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BRIYA PCS 401 I Street SW, 20024 3912 Georgia Avenue NW, 20011 CEDAR TREE ACADEMY PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 701 Howard Road SE, 20020 ACADEMY PCS (MC TERRELL) Waterfront Georgia Ave Petworth 3301 Wheeler Road SE, 20032 Federal Center SW Charter Anacostia Public Charter Congress Heights BROOKLAND MIDDLE SCHOOL Charter APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 1150 Michigan Avenue NE, 20017 CENTER CITY PCS - CAPITOL HILL PCS - COLUMBIA HEIGHTS 1503 East Capitol Street SE, 20003 DC BILINGUAL PCS 2750 14th Street NW, 20009 Brookland-CUA 33 Riggs Road NE, 20011 Stadium Armory Public Columbia Heights Charter Fort Totten Charter Charter BRUCE-MONROE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL @ PARK VIEW CENTER CITY PCS - PETWORTH 3560 Warder Street NW, 20010 510 Webster Street NW, 20011 DC PREP PCS - ANACOSTIA MIDDLE APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 2405 Martin Luther -

Dc Homeowners' Property Taxes Remain Lowest in The

An Affiliate of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 820 First Street NE, Suite 460 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 408-1080 Fax (202) 408-8173 www.dcfpi.org February 27, 2009 DC HOMEOWNERS’ PROPERTY TAXES REMAIN LOWEST IN THE REGION By Katie Kerstetter This week, District homeowners will receive their assessments for 2010 and their property tax bills for 2009. The new assessments are expected to decline modestly, after increasing significantly over the past several years. The new assessments won’t impact homeowners’ tax bills until next year, because this year’s bills are based on last year’s assessments. Yet even though 2009’s tax bills are based on a period when average assessments were rising, this analysis shows that property tax bills have decreased or risen only moderately for many homeowners in recent years. DC homeowners continue to enjoy the lowest average property tax bills in the region, largely due to property tax relief policies implemented in recent years. These policies include a Homestead Deduction1 increase from $30,000 to $67,500; a 10 percent cap on annual increases in taxable assessments; and an 11-cent property tax rate cut. The District also adopted a “calculated rate” provision that decreases the tax rate if property tax collections reach a certain target. As a result of these measures, most DC homeowners have seen their tax bills fall — or increase only modestly — over the past four years. In 2008, DC homeowners paid lower property taxes on average than homeowners in surrounding counties. Among homes with an average sales price of $500,000, DC homeowners paid an average tax of $2,725, compared to $3,504 in Montgomery County, $4,752 in PG County, and over $4,400 in Arlington and Fairfax counties. -

ANC 7E Submission

Government of the District of Columbia ADVISORY NEIGHBORHOOD COMMISSION 7E Marshall Heights ▪ Benning Ridge ▪ Capitol View ▪ Fort Davis 3939 Benning Rd. NE 7E01 – Veda Rasheed Washington, D.C. 20019 7E02 – Linda S. Green, Vice-Chair [email protected] 7E03 – Ebbon Allen www.anc7e.us 7E04 – Takiyah “TN” Tate Twitter: @ANC7E 7E05 – Victor Horton, 7E06 – Delia Houseal, Chair 7E07 – Yolanda Fields, Secretary/Treasurer Executive Assistant, Jemila James RESOLUTION #: 7E-20-002 Recommendations on the DC Comprehensive Plan January 14, 2020 WHEREAS, Advisory Neighborhood Commissions (ANCs) were created to “advise the Council of the District of Columbia, the Mayor, and each executive agency with respect to all proposed matters of District government policy,” including education; WHEREAS, the government of the District of Columbia by law is required to give “great weight” to comments from ANCs; WHEREAS, the Bowser Administration is committed to ensuring the public’s voices and views are reflected in the update of the Comprehensive Plan; WHEREAS, Advisory Neighborhood Commission (ANC) 7E has conducted several public engagement activities to gather feedback from residents; THEREFORE BEFORE IT RESOLVED: The Advisory Neighborhood Commission (ANC) 7E puts forward the following recommendations: FAR SOUTHEAST/NORTHEAST ELEMENT Recommendations After careful review and consideration, ANC7E Recommends that language be added to the Far Northeast/Southeast Element to address the following issues: 1702. Land Use 1702.4. We recommend the following text updates: Commercial uses are clustered in nodes along Minnesota Avenue, East Capitol Street, Naylor Road, Pennsylvania Avenue, Nannie Helen Burroughs Avenue, Division Avenue, Central Avenue SE, H Street SE, and Benning Road (NE and SE).