D.C.'S Disconnect Between Citywide Enrollment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROUTES LINE NAME Sunday Supplemental Service Note 1A,B Wilson Blvd-Vienna Sunday 1C Fair Oaks-Fairfax Blvd Sunday 2A Washington

Sunday Supplemental ROUTES LINE NAME Note Service 1A,B Wilson Blvd-Vienna Sunday 1C Fair Oaks-Fairfax Blvd Sunday 2A Washington Blvd-Dunn Loring Sunday 2B Fair Oaks-Jermantown Rd Sunday 3A Annandale Rd Sunday 3T Pimmit Hills No Service 3Y Lee Highway-Farragut Square No Service 4A,B Pershing Drive-Arlington Boulevard Sunday 5A DC-Dulles Sunday 7A,F,Y Lincolnia-North Fairlington Sunday 7C,P Park Center-Pentagon No Service 7M Mark Center-Pentagon Weekday 7W Lincolnia-Pentagon No Service 8S,W,Z Foxchase-Seminary Valley No Service 10A,E,N Alexandria-Pentagon Sunday 10B Hunting Point-Ballston Sunday 11Y Mt Vernon Express No Service 15K Chain Bridge Road No Service 16A,C,E Columbia Pike Sunday 16G,H Columbia Pike-Pentagon City Sunday 16L Annandale-Skyline City-Pentagon No Service 16Y Columbia Pike-Farragut Square No Service 17B,M Kings Park No Service 17G,H,K,L Kings Park Express Saturday Supplemental 17G only 18G,H,J Orange Hunt No Service 18P Burke Centre Weekday 21A,D Landmark-Bren Mar Pk-Pentagon No Service 22A,C,F Barcroft-South Fairlington Sunday 23A,B,T McLean-Crystal City Sunday 25B Landmark-Ballston Sunday 26A Annandale-East Falls Church No Service 28A Leesburg Pike Sunday 28F,G Skyline City No Service 29C,G Annandale No Service 29K,N Alexandria-Fairfax Sunday 29W Braeburn Dr-Pentagon Express No Service 30N,30S Friendship Hghts-Southeast Sunday 31,33 Wisconsin Avenue Sunday 32,34,36 Pennsylvania Avenue Sunday 37 Wisconsin Avenue Limited No Service 38B Ballston-Farragut Square Sunday 39 Pennsylvania Avenue Limited No Service 42,43 Mount -

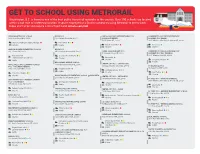

GET to SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C

GET TO SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C. is home to one of the best public transit rail networks in the country. Over 100 schools are located within a half mile of a Metrorail station. If you’re employed at a District school, try using Metrorail to get to work. Rides start at $2 and require a SmarTrip® card. wmata.com/rail AIDAN MONTESSORI SCHOOL BRIYA PCS CARLOS ROSARIO INTERNATIONAL PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 2700 27th Street NW, 20008 100 Gallatin Street NE, 20011 (SONIA GUTIERREZ) ACADEMY PCS (MAIN) 514 V Street NE, 20002 2405 Martin Luther King Jr Avenue SE, 20020 Woodley Park-Zoo Adams Morgan Fort Totten Private Charter Rhode Island Ave Anacostia Charter Charter AMIDON-BOWEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BRIYA PCS 401 I Street SW, 20024 3912 Georgia Avenue NW, 20011 CEDAR TREE ACADEMY PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 701 Howard Road SE, 20020 ACADEMY PCS (MC TERRELL) Waterfront Georgia Ave Petworth 3301 Wheeler Road SE, 20032 Federal Center SW Charter Anacostia Public Charter Congress Heights BROOKLAND MIDDLE SCHOOL Charter APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 1150 Michigan Avenue NE, 20017 CENTER CITY PCS - CAPITOL HILL PCS - COLUMBIA HEIGHTS 1503 East Capitol Street SE, 20003 DC BILINGUAL PCS 2750 14th Street NW, 20009 Brookland-CUA 33 Riggs Road NE, 20011 Stadium Armory Public Columbia Heights Charter Fort Totten Charter Charter BRUCE-MONROE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL @ PARK VIEW CENTER CITY PCS - PETWORTH 3560 Warder Street NW, 20010 510 Webster Street NW, 20011 DC PREP PCS - ANACOSTIA MIDDLE APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 2405 Martin Luther -

Dc Homeowners' Property Taxes Remain Lowest in The

An Affiliate of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 820 First Street NE, Suite 460 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 408-1080 Fax (202) 408-8173 www.dcfpi.org February 27, 2009 DC HOMEOWNERS’ PROPERTY TAXES REMAIN LOWEST IN THE REGION By Katie Kerstetter This week, District homeowners will receive their assessments for 2010 and their property tax bills for 2009. The new assessments are expected to decline modestly, after increasing significantly over the past several years. The new assessments won’t impact homeowners’ tax bills until next year, because this year’s bills are based on last year’s assessments. Yet even though 2009’s tax bills are based on a period when average assessments were rising, this analysis shows that property tax bills have decreased or risen only moderately for many homeowners in recent years. DC homeowners continue to enjoy the lowest average property tax bills in the region, largely due to property tax relief policies implemented in recent years. These policies include a Homestead Deduction1 increase from $30,000 to $67,500; a 10 percent cap on annual increases in taxable assessments; and an 11-cent property tax rate cut. The District also adopted a “calculated rate” provision that decreases the tax rate if property tax collections reach a certain target. As a result of these measures, most DC homeowners have seen their tax bills fall — or increase only modestly — over the past four years. In 2008, DC homeowners paid lower property taxes on average than homeowners in surrounding counties. Among homes with an average sales price of $500,000, DC homeowners paid an average tax of $2,725, compared to $3,504 in Montgomery County, $4,752 in PG County, and over $4,400 in Arlington and Fairfax counties. -

22206 18Th Street Flyer

Washington, DC 10 Minute Drive Time Crestwood Melvin Hazen Park The Catholic University of America McLean Gardens American University Po rte r S tr ee t N W Old Soldiers’ Home Golf Course Mount Pleasant Smithsonian National Zoological Columbia Heights MedStar M Cathedral Heights a Park Washington ss ac h C u Hospital s o e n tt n Center s e A c v t e i n c u u e t Woodley Park N A W v e n u Rock Creek e N Park Glover W Howard Archbold Park University United States Naval Observatory Adams F Glover Park o x Morgan h a l l R o a d N W W N e Bloomingdale nu ve A a rid Kalorama lo W Burleith F N e u n e v A e ir Eckington h s Reservoir Road p m Shaw a 1 H 6 t w h e N S t r e e t Foxhall Logan Circle Truxton Circle M Georgetown E a NW N cArt ue ue hur en ven Bl Av A vd Dupont Circle nd ork sla Y e I ew od N Rh Can al Road NW M Street West End Mount Vernon Square Downtown Wa K Street shington Memorial Parkway 7 t W h e N S nu t ve r A e ork e w Y t Chinatown Ne Penn Quarter Residential RosslynTotal Average Daytime Population Households Household Population Judiciary Square Income The White House 161,743 85,992 $134,445 344,027 Wells Fargo Bank Star Trading Starbucks Osteria Al Volo W N Epic Philly Steaks Neighborhood some of DC’s liveliestnightspots. -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

Stream Health at Select Tributaries of Rock Creek in Washington, DC 2010-2018

Report on Stream Health at Select Tributaries of Rock Creek in Washington, DC 2010-2018 Audubon Naturalist Society Water Quality Monitoring Program Cathy Wiss, Program Coordinator December 2018 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 2 II. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 3 III. Site Descriptions ............................................................................................................................... 4 Pinehurst Branch ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Melvin Hazen Run ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Normanstone Run ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Broad Branch........................................................................................................................................... 11 IV. Benthic Macroinvertebrate Monitoring ......................................................................................... 11 V. Stream Health Ratings ....................................................................................................................... -

Compiled Public Comments Wednesday, August 7 | Mt

PHASE 2 COMPILED PUBLIC COMMENTS WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 7 | MT. PLEASANT LIBRARY 1 WORKBOOK COMMENTS Staff did their best to transcribe all handwritten comments. Originals are available upon request at the offices of the National Capital Planning Commission. Frederic Harwood | Shaw, DC Approach 1: Leaves the skyline looking like a pancake with a pencil sticking out of it. Limits the city’s economic growth, jobs, retail. Limits the development of the “creative city,” a place where creative people meet, interact, cross‐fertilize to create technology, ideas, the future. Limits taxes to help lower income residents—taxes from increased densities of professionals and creative types generate tax revenue to build schools, recreation, and low income housing. Approach 2: The relationship of height to streeth width is irrelevant. Philadelphia has 1,000 foot tall buildings in 2 & 3 lane streets (40‐60 feet). What matters is the quality of what goes on at street level—restaurants, retail, theaters, open spaces, plazas—not how high the buildings are. We are over‐planning and over‐engineering the building heights. New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, do not tie building height to street width—put something interesting on the street and building heights will be irrelevant. Approach 3: Yes to all three. Eliminating height limits would especially benefit under‐developed areas such as Benning Road, Anacostia—where the economic benefits of high commercial towers would trickle into the surrounding neighborhoods and provide jobs, both professional and service jobs. L’Enfant city would benefit because it is nearly 100% built out and economic growth stagnating. The bowl outside L’Enfant city would benefit with housing, people, residents who would support retail, creating creative jobs, and pay income and real estate taxes to benefit all residents. -

Housing in the Nation's Capital

Housing in the Nation’s2005 Capital Foreword . 2 About the Authors. 4 Acknowledgments. 4 Executive Summary . 5 Introduction. 12 Chapter 1 City Revitalization and Regional Context . 15 Chapter 2 Contrasts Across the District’s Neighborhoods . 20 Chapter 3 Homeownership Out of Reach. 29 Chapter 4 Narrowing Rental Options. 35 Chapter 5 Closing the Gap . 43 Endnotes . 53 References . 56 Appendices . 57 Prepared for the Fannie Mae Foundation by the Urban Institute Margery Austin Turner G. Thomas Kingsley Kathryn L. S. Pettit Jessica Cigna Michael Eiseman HOUSING IN THE NATION’S CAPITAL 2005 Foreword Last year’s Housing in the Nation’s Capital These trends provide cause for celebration. adopted a regional perspective to illuminate the The District stands at the center of what is housing affordability challenges confronting arguably the nation’s strongest regional econ- Washington, D.C. The report showed that the omy, and the city’s housing market is sizzling. region’s strong but geographically unbalanced But these facts mask a much more somber growth is fueling sprawl, degrading the envi- reality, one of mounting hardship and declining ronment, and — most ominously — straining opportunity for many District families. Home the capacity of working families to find homes price escalation is squeezing families — espe- they can afford. The report provided a portrait cially minority and working families — out of of a region under stress, struggling against the city’s housing market. Between 2000 and forces with the potential to do real harm to 2003, the share of minority home buyers in the the quality of life throughout the Washington District fell from 43 percent to 37 percent. -

Art All Night History

ART ALL NIGHT HISTORY Art All Night: Nuit Blanche DC was first produced in 2011 by Ariana Austin and Alexander Padro of Shaw Main Streets, and funded with a grant from the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities. Ms. Austin and Mr. Padro’s goal was to bring Paris’ famed Nuit Blanche overnight arts and culture festival to Washington, DC and to produce an event that would unite the creative, cultural and international capital of our city. They redesigned the original festival and transformed it from an exclusively arts focused activity into a creative placemaking opportunity that gave equal importance to the art and to the places where it took place. In short, they created a promotional event that maximized its impact on neighborhood businesses. Curated by Ms. Austin and a team of volunteers, the first festival exceeded all expectations and attracted 15,000 attendees. A Taste of Art All Night followed in 2012 in the Penn Quarter, presented by the Downtown BID. In 2013, Shaw Main Streets brought back the full festival for an encore, with funding from the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities and the Department of Small and Local Business Development. In both 2011 and 2013, the event brought unprecedented attention to the DC metropolitan area’s art scene through the live indoor and outdoor musical performances and art installations which were presented in vacant commercial spaces and warehouses, in public spaces (libraries, recreation centers, and parks), and in theaters and art galleries. Notably, programming even took place inside businesses, some of which had never opened at night. -

DC Kids Count E-Databook

DC ACTION FOR CHILDREN DC KIDS COUNT e-Databook “People I meet... the effect upon me of my early life... of the ward and city I live in... of the nation” —Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass Every city has many identities, depending on But Washington, aka DC, is also simply a who you ask. A legislator, a police officer, a hometown, where many people live their daily coach or a clerk might describe the same lives, raise their children and create community city’s people, culture and reputation in starkly and the future together. different terms. Washington is home to 100,000 children We are the nation’s capital, the official under 18. They are one in six DC residents. Washington that so many politicians run The number of children under the age of 5 has campaigns against. We are an international started to grow again after almost a decade of center of power, featuring stately embassies and decline.1 serving as the temporary home to diplomats. This DC KIDS COUNT e-databook is for and For some Americans, Washington is a code about them. word for the bubble where politicians hobnob with “fat cats,” bureaucrats operate and media Why Place Matters in the Lives of swarm over the latest scandal. Children (and Families) For some Americans, Washington is a place to Children grow up (and families live) in specific visit with their children to learn about history, places: neighborhoods. How well these read the original Declaration of Independence, neighborhoods are doing affects how well the stand on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and children and their families who live in them are 1. -

Line Name Routes Per Line Benning Road-H Street X2 DC Garfield

Routes per Line Name Line Jurisdicti on Benning Road-H Street X2 DC Garfield-Anacostia Loop W6,8 DC East Capitol Street-Cardozo 96,97 DC Connecticut Avenue L1,2 DC Brookland-Fort Lincoln H6 DC Crosstown H2,3,4 DC Fort Totten-Petworth 60,64 DC Benning Heights-Alabama Ave V7,8 DC Hospital Center D8 DC Glover Park-Dupont Circle D2 DC 14th Street 52,54 DC Sibley Hospital - Stadium-Armory D6 DC Ivy City-Franklin Square D4 DC Takoma-Petworth 62,63 DC Massachusetts Avenue N2,4,6 DC Military Road-Crosstown E4 DC Sheriff Road-River Terrace U4 DC Ivy City-Fort Totten E2 DC Mount Pleasant 42,43 DC North Capitol Street 80 DC P Street-LeDroit Park G2 DC Park Road-Brookland H8,9 DC Pennsylvania Avenue 32,34,36 DC Deanwood-Alabama Avenue W4 DC Wisconsin Avenue 31,33 DC Rhode Island Avenue G8 DC Georgia Avenue Limited 79 DC 16th Street S2,4 DC Friendship Heights-Southeast 30N,30S DC Georgia Avenue-7th Street 70 DC Convention Center-Southwest Waterfront 74 DC U Street-Garfield 90,92 DC Capitol Heights-Minnesota Ave V2,4 DC Deanwood-Minnesota Ave Sta U7 DC Mayfair-Marshall Heights U5,6 DC Bladensburg Road-Anacostia B2 DC United Medical Center-Anacostia W2,3 DC Anacostia-Eckington P6 DC Anacostia-Congress Heights A2,6,7,8 DC Anacostia-Fort Drum A4,W5 DC National Harbor-Southern Ave NH1 MD Annapolis Road T18 MD Greenbelt-Twinbrook C2,4 MD Bethesda-Silver Spring J1,2 MD National Harbor-Alexandria NH2 MD Chillum Road F1,2 MD District Heights-Seat Pleasant V14 MD Eastover-Addison Road P12 MD Forestville K12 MD Georgia Avenue-Maryland Y2,7,8 MD Marlboro Pike J12 MD Marlow Heights-Temple Hills H11,12,13 MD College Park 83,83X,86 MD New Hampshire Avenue-Maryland K6 MD Martin Luther King Jr. -

Collections Survey FY 2017 Report and Preliminary Finding Guide

Collections Survey FY 2017 Report and Preliminary Finding Guide DC Oral History Collaborative A project of Humanities DC and the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. for The District of Columbia Public Library Contract No. DCPL-2017-C-0008 Prepared by Anna F. Kaplan Oral History Project Surveyor, DC Oral History Collaborative August 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction, Scope and Purpose………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Methodology …………………………………………….…………………………………………………………. 4 List of Repositories Surveyed and Abberviations.………………………………………………….. 5 Map of Repository Locations ……………………………………………………………….……………….. 6 Summary of Findings at Each Repository ……………………………………………………………… 7 Repository Contact Information ……………………………………………………………….………... 17 Repositories Contacted with No Response ……………………………………………………..…… 21 Additional Repositories to Approach in the Future ………………………………………….….. 21 Organizations Currently Conducting Oral Histories …………………………………………..... 22 Index of Narrator Names with Repository Locations …………………………………………… 23 Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………………………………….... 67 1 INTRODUCTION The DC Oral History Collaborative is an ambitious city-wide initiative to document and preserve the history of Washington’s residents and communities through the collection of oral histories. The project will survey and publicize existing oral history collections, provide grants and training for scholars and amateur historians to launch new oral history projects, and establish an interactive, accessible platform where the city’s memories can benefit residents and scholars for generations to come. Origins of the DC Oral History Collaborative In 2016 D.C. Councilmember David Grosso expressed an interest in helping the citizens of Washington, D.C. gain access to hundreds of oral histories that illuminate our shared history but are difficult to find. In addition, having seen initiatives underway in other cities, the councilmember wanted to encourage the collection of new oral histories from elders and others whose stories need to be told and recorded for future generations.