Th E Ex Odusof He a Lt H Pr Ofessionals Fr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

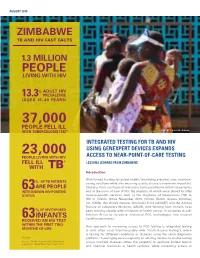

Integrated Testing for TB and HIV Zimbabwe

AUGUST 2019 ZIMBABWE TB AND HIV FAST FACTS 1.3 MILLION PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV % ADULT HIV 13.3 PREVALENCE (AGES 15–49 YEARS) 37,000 PEOPLE FELL ILL WITH TUBERCULOSIS (TB)* © UNICEF/Costa/Zimbabwe INTEGRATED TESTING FOR TB AND HIV 23,000 USING GENEXPERT DEVICES EXPANDS PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV ACCESS TO NEAR-POINT-OF-CARE TESTING FELL ILL * LESSONS LEARNED FROM ZIMBABWE WITH TB Introduction With limited funding for global health, identifying practical, cost- and time- OF TB PATIENTS % saving solutions while also ensuring quality of care is evermore important. 63ARE PEOPLE Globally, there are fleets of molecular testing platforms within laboratories WITH KNOWN HIV-POSITIVE and at the point of care (POC), the majority of which were placed to offer STATUS disease-specific services such as the diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) or HIV in infants. Since November 2015, Clinton Health Access Initiative, Inc. (CHAI), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the African Society of Laboratory Medicine (ASLM), with funding from Unitaid, have % OF HIV-EXPOSED been working closely with ministries of health across 10 countries in sub- Saharan Africa to introduce innovative POC technologies into national INFANTS 1 63 health programmes. RECEIVED AN HIV TEST WITHIN THE FIRST TWO One approach to increasing access to POC testing is integrated testing MONTHS OF LIFE (a term often used interchangeably with “multi-disease testing”), which is testing for different conditions or diseases using the same diagnostic *Annually platform.2 Leveraging excess capacity on existing devices to enable testing Sources: UNAIDS estimates 2019; World Health across multiple diseases offers the potential to optimize limited human Organization, ‘Global Tuberculosis Report 2018’ and financial resources at health facilities, while increasing access to rapid testing services. -

Grant Assistance for Grassroots Human Projects in Zimbabwe

Grant Assistance for Grassroots Human Projects in Zimbabwe Amount Amount No Year Project Title Implementing Organisation District (US) (yen) 1 1989 Mbungu Primary School Development Project Mbungu Primary School Gokwe 16,807 2,067,261 2 1989 Sewing and Knitting Project Rutowa Young Women's Club Gutu 5,434 668,382 3 1990 Children's Agricultural Project Save the Children USA Nyangombe 8,659 1,177,624 Mbungo Uniform Clothing Tailoring Workshop 4 1990 Mbungo Women's Club Masvingo 14,767 2,008,312 Project Construction of Gardening Facilities in 5 1991 Cold Comfort Farm Trust Harare 42,103 5,431,287 Support of Small-Scale Farmers 6 1991 Pre-School Project Kwayedza Cooperative Gweru 33,226 4,286,154 Committee for the Rural Technical 7 1992 Rural Technical Training Project Murehwa 38,266 4,936,314 Training Project 8 1992 Mukotosi Schools Project Mukotosi Project Committee Chivi 20,912 2,697,648 9 1992 Bvute Dam Project Bvute Dam Project Committee Chivi 3,558 458,982 10 1992 Uranda Clinic Project Uranda Clinic Project Committee Chivi 1,309 168,861 11 1992 Utete Dam Project Utete Dam Project Committee Chivi 8,051 1,038,579 Drilling of Ten Boreholes for Water and 12 1993 Irrigation in the Inyathi and Tsholotsho Help Age Zimbabwe Tsholotsho 41,574 5,072,028 PromotionDistricts of ofSocialForestry Matabeleland andManagement Zimbabwe National Conservation 13 1993 Buhera 46,682 5,695,204 ofWoodlands inCommunalAreas ofZimbabwe Trust Expansion of St. Mary's Gavhunga Primary St. Mary's Gavhunga Primary 14 1994 Kadoma 29,916 3,171,096 School School Tsitshatshawa -

ANALYSIS of SPATIAL PATTERNS of SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, and WELFARE INEQUALITY in ZIMBABWE 1 Analysis of Spatial

ANALYSIS OF SPATIAL PATTERNS OF SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, AND WELFARE INEQUALITY IN ZIMBABWE 1 Analysis of Spatial Public Disclosure Authorized Patterns of Settlement, Internal Migration, and Welfare Inequality in Zimbabwe Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Rob Swinkels Therese Norman Brian Blankespoor WITH Nyasha Munditi Public Disclosure Authorized Herbert Zvirereh World Bank Group April 18, 2019 Based on ZIMSTAT data Zimbabwe District Map, 2012 Zimbabwe Altitude Map ii ANALYSIS OF SPATIAL PATTERNS OF SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, AND WELFARE INEQUALITY IN ZIMBABWE TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii ABSTRACT v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ix ABBREVIATIONS xv 1. INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES 1 2. SPATIAL ELEMENTS OF SETTLEMENT: WHERE DID PEOPLE LIVE IN 2012? 9 3. RECENT POPULATION MOVEMENTS 27 4. REASONS BEHIND THE SPATIAL SETTLEMENT PATTERN AND POPULATION MOVEMENTS 39 5. CONSEQUENCES OF THE POPULATION’S SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION 53 6. POLICY DISCUSSION 71 AREAS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH 81 REFERENCES 83 APPENDIX A. SUPPLEMENTAL MAPS AND CHARTS 87 APPENDIX B. RESULTS OF REGRESSION ANALYSIS 99 APPENDIX C. EXAMPLE OF LOCAL DEVELOPMENT INDEX 111 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by a team led by Rob Swinkels, comprising Therese Norman and Brian Blankespoor. Important background work was conducted by Nyasha Munditi and Herbert Zvirereh. Wishy Chipiro provided valuable technical support. Overall guidance was provided by Andrew Dabalen, Ruth Hill, and Mukami Kariuki. Peer reviewers were Luc Christiaensen, Nagaraja Rao Harshadeep, Hans Hoogeveen, Kirsten Hommann, and Marko Kwaramba. Tawanda Chingozha commented on an earlier draft and shared the shapefiles of the Zimbabwe farmland use types. Yondela Silimela, Carli Bunding-Venter, Leslie Nii Odartey Mills, and Aiga Stokenberga provided inputs to the policy section. -

Original Research Article the Spatial Dimension of Health Service

Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences (SJAMS) ISSN 2320-6691 (Online) Sch. J. App. Med. Sci., 2016; 4(1C):201-204 ISSN 2347-954X (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publisher (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) www.saspublisher.com Original Research Article The Spatial Dimension of Health Service Provision in Mashonaland West Province, Zimbabwe Takudzwa Mhandu, Dr Evans Chazireni Great Zimbabwe University, P O Box 1235, Masvingo, Zimbabwe *Corresponding author Dr Evans Chazireni Email: Abstract: Zimbabwe like many other developing countries has serious problems in its healthcare system. The quality of health service provision in Zimbabwe is generally poor Chazireni. Different parts of the country have serious healthcare problems. Mashonaland West, like other provinces in Zimbabwe, experiences numerous healthcare challenges. The research examines health service provision in Mashonaland West province in Zimbabwe. Data for this study was collected from ZIMSTAT published census reports and Ministry of health and Child Welfare published national health profiles. The analysis of the data was done through the composite index method. The calculated composite indices were used to rank the districts according to the level of health service provision. The researcher found out that there overall, the conditions of health service provision in Mashonaland West province is poor and that there are health service disparities among administrative districts in Mashonaland West province of Zimbabwe. There are many reasons which contribute to disparities in health care services at different levels (global, continental, regional, national and district level). It emerged from the research that the disparities are due to social, economic, physical and political factors. -

A Golden Opportunity: Scoping Study of Artisanal and Small Scale Gold Mining in Zimbabwe

pactworld.orgpactworld.org July 2015July 2015 pactworld.orgpactworld.org JulyJuly 20152015 AA Golden Golden Opportunity:Opportunity: ScopingScoping Study Study of Artisanal of Artisanal and Small Scale Gold Mining and Small Scale Gold Mining inin Zimbabwe in Zimbabwe SUBMITTED TO Phil Johnston Economic Adviser UK Department for International Development Zimbabwe British Embassy 3 Norfolk Road, Mount Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe TEL: +263 (0)4 8585 5375 E-MAIL: [email protected] UPDATED DOCUMENT SUBMITTED ON 22 June2015 SUBMITTED BY Pact Institute, 1828 L Street, NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20036, USA TEL: +1-202-466-5666 FAX: +1-202-466-5665 [email protected] CONTACT Peter Mudzwiti, ASM Scoping Study Lead E-MAIL: [email protected] Trevor Maisiri Country Director, Pact Zimbabwe TEL: +263 (0)4 250 942, +263 (0)772 414 465 E-MAIL: [email protected] ii Foreword Dear reader, We all rely on stereotypes to make sense of the world around us. The problem, of course, is that stereotypes aren’t always accurate. Many people believe that the typical artisanal gold miner in Zimbabwe is a single, migratory man in his early 20s who has no education, gambles away his money, and is likely to contract HIV. But the picture of the miners who participated in this study is rather different. In fact, mining is carried out by men, women, youth and children. The average miner is older and married with more children than non-miners in their community. They have more formal education, and earn and save more money than non-miners. And despite assumptions about lifestyles, miners are no more likely to be HIV-positive than non-miners. -

Zimbabwe Health Cluster Bulletin

Zimbabwe Health Cluster bulletin Bulletin No 9 15-23 March 2009 Highlights: Cholera outbreak situational update • About 92,037 cases and From the beginning of the cholera out- 4050 deaths, CFR 4.4% break in August 2008 to date, all prov- and I-CFR 1.8% inces and 56 districts have been af- fected. By 21 March, a total of 92, 037 • Outbreak appears to be on the decrease cases and 4,105 deaths had been re- ported, giving a crude Case Fatality Ratio • Cholera hotspots now in (CFR) of 4.4%. This week, 51% of all 62 Harare and Chitungwiza districts have reported. cities Preliminary results from an ongoing • Cholera Command & analysis of the cholera outbreak by WHO Control Centre continue with provincial sup- epidemiologists indicate that the out- port and monitoring visits break is indeed slowing down. While this is good news, some areas remain hot- spots especially Chitungwiza and Harare city, which are affected by water short- ages and poor waste disposal systems. Chitungwiza is of particular interest be- cause it was the initial focus of the out- Inside this issue: break in August 2008. A further risk analysis in Chitungwiza and Cholera situation 1 Harare is being carried out by a monitor- ing and evaluation team from the cholera Missions to Zimbabwe 2 command and control centre. Coordination updates 2 Mashonaland west province has also re- ported, Kadoma district specifically, is C4 weekly meetings 2 experiencing an upsurge in cases. A team from the C4 has been dispatched Who, what, where, 3 this week to investigate this. -

Health Cluster Bulletin 11Ver2

Zimbabwe Health Cluster bulletin Bulletin No 11 1-15 April 2009 Highlights: Cholera outbreak situation update • About 96, 473 cases and 4,204 deaths, CFR 4.4% Following a 9 week decline trend in cholera cases, an upsurge was reported during epidemi- • Sustained decline of ological week 15. Batch reporting in three districts may have contributed to this slight in- the outbreak crease. • Cholera hotspots in The cumulative number of Mashonaland west, Cholera in Zimbabwe reported cholera cases was Harare and Chitungwiza 17 Aug 08 to 11th April 09 96, 473 and 4204 deaths with 10,000 cities cumulative Case Fatality Rate 8,000 Cases Deaths (CFR) as of 4.4 as of 15 April. During week 15, a 17% de- 6,000 crease in cases and 5% in- 4,000 crease in deaths was re- Number ported. The crude CFR is 2.7% 2,000 compared to 2.9% of week 14 0 while the I-CFR is 1.8% com- pared to 2.7% of week 14. The w2 w4 w6 w8 w36 w38 w40 w42 w44 w46 w48 w50 w52 w10 w12 w14 CFR has been steadily de- weeks clined although the proportion of deaths in health facilities has increased compared to Cholera in Zimbabw e from 16 Nov 08 to 11th A pril 09 those reported in the commu- W eekly c rude and institutional c ase-fatality ratios 10 nity. CFR 9 This is probably an indication Inside this issue: 8 iCFR 7 of more people accessing 6 treatment and/or the increas- Cholera situation 1 5 ing role of other co- 4 morbidities presenting along- ORPs in cholera 2 3 management percent side cholera. -

33 Internet: Telephone: 202 473 1000

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized © International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Internet: www.worldbank.org; Telephone: 202 473 1000 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or other partner institutions or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colours, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported licence (CC BY 3.0 IGO) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution – Please cite the work as follows: The World Bank. 2018. Estimating the efficiency gains made through the integration of HIV and sexual reproductive health services in Zimbabwe. Washington DC: World Bank. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO. Translations – If you create a translation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an official World Bank translation. -

Zimbabwe – Cholera Outbreak

BUREAU FOR DEMOCRACY, CONFLICT, AND HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (DCHA) OFFICE OF U.S. FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) Zimbabwe – Cholera Outbreak Fact Sheet #13, Fiscal Year (FY) 2009 April 2, 2009 Note: The last fact sheet was dated March 19, 2009. KEY DEVELOPMENTS • Since the cholera outbreak began in August 2008, the disease has spread to 60 of Zimbabwe’s 62 districts. As of April 1, nearly 94,300 reported cases of cholera had caused more than 4,100 deaths, according to the U.N. World Health Organization (WHO). On March 21, the total caseload exceeded 92,000 cases, the previous WHO estimate of the outbreak’s likeliest overall scope. • On April 1, WHO reported a sustained decline in the rates of cholera deaths and new cases over the past eight weeks. On March 27, the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) stressed the ongoing need for vigilant surveillance and robust response activities despite the declining caseload countrywide. • On March 24, WHO recorded the first cholera case in Umzingwane District, Matabeleland South Province. To date, however, the organization has not reported additional cases in the district. NUMBERS AT A GLANCE SOURCE Total Reported Cholera Cases in Zimbabwe 94,277 WHO – April 1, 2009 Total Reported Cholera Deaths in Zimbabwe 4,127 WHO – April 1, 2009 FY 2009 HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Total USAID Humanitarian Assistance to Zimbabwe for the Cholera Outbreak ...........................................$7,305,529 CURRENT SITUATION • On March 30, WHO reported that the outbreak remained uncontrolled, despite the nationwide decline in the weekly rates of cholera deaths and new cases. -

Sanyati District Mashonaland West

Food and Nutrition Security in the Context of COVID-19 in Zimbabwe Documentation of the Role of Traditional Leadership in AddressingSANYATI Food DISTRICT and Nutrition InsecurityResponse in Strategy Zimbabwe Sanyati District Mashonaland West Introduction Sanyati district is one of the two new districts established in 2007 from the larger Kadoma district. It lies in about 120km south west of the city province Chinhoyi and about 140km west of Harare. The district setup covers urban and rural council following the splitting of Kadoma district into Sanyati & Mhondoro Ngezi. The administrative office (DDC’s Office),Documen government ministriest aandtion departments of the Role of are situated in Kadoma city. Sanyati is bordered by Makonde and Gokwe in the north, Kwekwe south, Mhondoro Ngezi and Chegutu in the east. The district comprises Tof theraditional DDC’s office, the urban Leader & rural ship in municipal council and has around 28 ministerial departments which are: Agritex, health, education, forestry, youth, women affairs, livestock, social welfare, AddrSMEs, P.S. C,essing Housing, EMA, F publicood works, and Nutrition justice, prisons, labour employment, lands, mines, transport, veterinary,Insecurity mechanization, ZIMSTAT,in Zimbab we E.M.A, labour and disputes, DDF, Cotton research, ZESA, Tel-one and Home affairs. In developing this profile, the consultants collaborated with the district staff in data collection from the various departments of the district and sectoral ministries. A participatory approach was used with a purpose of creating a relevant capacity among the district officials which can be applied to review or update the profile in the future. This profile provides a peep of the district for just 13 years since it was established. -

Zimbabwe's Irrigation Potential

USAID STRATEGIC ECONOMIC RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS – ZIMBABWE (SERA) PROGRAM ZIMBABWE’S IRRIGATION POTENTIAL: MANAGEMENT MODELS FOR IRRIGATION SCHEMES AND A POLICY FRAMEWORK FOR EFFICIENT IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE CONTRACT NO. AID-613-C-11-00001 SEPTEMBER 2016 This report was produced by Nathan Associates Inc. for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). i USAID STRATEGIC ECONOMIC RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS – ZIMBABWE (SERA) PROGRAM ZIMBABWE’S IRRIGATION POTENTIAL: MANAGEMENT MODELS FOR IRRIGATION SCHEMES AND A POLICY FRAMEWORK FOR EFFICIENT IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE CONTRACT NO. AID-613-C-11-00001 Program Title: USAID Strategic Economic Research & Analysis – Zimbabwe (SERA) Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Zimbabwe Contract Number: AID-613-C-11-00001 Contractor: Nathan Associates Inc. Date of Publication: September 2016 Author: Oniward Svubure DISCLAIMER This document is made possible by the support of the American people through USAID. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. ii Contents LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES .................................................................................................................. v ACRONYMS .............................................................................................................................................. vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... -

Livelihoods and Natural Resource Management Dynamics

LIVELIHOODS AND NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT DYNAMICS IN FAST TRACK LAND RESETTLEMENTS, KWEKWE DISTRICT, ZIMBABWE Farai Mumanyi 2014 A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Agriculture (Extension and Rural Resource Management) In the College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science School of Agricultural, Earth and Environmental Sciences University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg ABSTRACT The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate an Agricultural community and its system of Natural Resource Management (NRM) in the post–Fast Track Land Reform Program (FTLRP) era in Zimbabwe. The study contributes to understanding issues facing Agricultural Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) set ups in two resettlement models. The aim was to establish the influence that the FTLRP had on emergent practice and use of the natural resource base. The main task was to explore the patterns of natural resource use within the dynamics of culture, vulnerability and governance issues. The researcher deliberately enriched the case study with interviews, questionnaires, focus group discussions and participatory observations to promote triangulation (confirmation) of results. The field work for the study was carried out in Kwekwe District in the Midlands Province of Zimbabwe. The main part of the district falls in Agro ecological zone III and the smaller part in zone IV. Agro ecological zone III is a semi-intensive farming area prone to sporadic seasonal droughts, long-lasting, mid-season dry spells and the unpredictable onset of the rainy season. Agro ecological zone IV is subject to drought and dry spells in summer, rendering the area unsuitable for arable farming but favourable for semi-extensive beef production.