Second Report of the Portfolio Committee On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres Chirumhanzu District Team 1 Ward Centre Dates 18 Mwire primary school 10/06/13-11/06/13 18 Tokwe 4 clinic 12/06/13-13/06/13 18 Chingegomo primary school 14/06/13-15/06/13 16 Chishuku Seondary school 16/06/13-18/06/13 9 Upfumba Secondary school 19/06/13-21/06/13 3 Mutya primary school 22/06/13-24/06/13 2 Gonawapotera secondary school 25/06/13-27/06/13 20 Wildegroove primary school 28/06/13-29/06/13 15 Kushinga primary school 30/06/13-02/07/13 12 Huchu compound 03/07/13-04/-07/13 12 Central estates HQ 5/7/13 20 Mtao/Fair Field compound 6/7/13 12 Chiudza homestead 07/07/13-08/06/13 14 Njerere primary school 9/7/13 Team 2 Ward Centre Dates 22 Hillview Secondary school 10/07/13-12/07/13 17 Lalapanzi Secondary school 13/07/13-15/07/13 16 Makuti homestead 16/06/13-17/06/13 1 Mapiravana Secondary school 18/06/13-19/06/13 9 Siyahukwe Secondary school 20/06/13-23/06/13 4 Chizvinire primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 21 Mukomberana Seconadry school 26/06/13-29/06/13 20 Union primary school 30/06/13-01/07/13 15 Nyikavanhu primary school 02/07/13-03/07/13 19 Musens primary school 04/07/13-06/07/13 16 Utah primary school 07/7/13-09/07/13 Team 3 Ward Centre Dates 11 Faerdan primary school 10/07/13-11/07/13 11 Chamakanda Secondary school 12/07/13-14/07/13 11 Chamakanda primary school 15/07/13-16/07/13 5 Chizhou Secondary school 17/06/13-16/06/13 3 Chilimanzi primary school 21/06/13-23/06/13 25 Maponda primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 6 Holy Cross seconadry school 26/06/13-28/06/13 20 New England Secondary -

Integrated Testing for TB and HIV Zimbabwe

AUGUST 2019 ZIMBABWE TB AND HIV FAST FACTS 1.3 MILLION PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV % ADULT HIV 13.3 PREVALENCE (AGES 15–49 YEARS) 37,000 PEOPLE FELL ILL WITH TUBERCULOSIS (TB)* © UNICEF/Costa/Zimbabwe INTEGRATED TESTING FOR TB AND HIV 23,000 USING GENEXPERT DEVICES EXPANDS PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV ACCESS TO NEAR-POINT-OF-CARE TESTING FELL ILL * LESSONS LEARNED FROM ZIMBABWE WITH TB Introduction With limited funding for global health, identifying practical, cost- and time- OF TB PATIENTS % saving solutions while also ensuring quality of care is evermore important. 63ARE PEOPLE Globally, there are fleets of molecular testing platforms within laboratories WITH KNOWN HIV-POSITIVE and at the point of care (POC), the majority of which were placed to offer STATUS disease-specific services such as the diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) or HIV in infants. Since November 2015, Clinton Health Access Initiative, Inc. (CHAI), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the African Society of Laboratory Medicine (ASLM), with funding from Unitaid, have % OF HIV-EXPOSED been working closely with ministries of health across 10 countries in sub- Saharan Africa to introduce innovative POC technologies into national INFANTS 1 63 health programmes. RECEIVED AN HIV TEST WITHIN THE FIRST TWO One approach to increasing access to POC testing is integrated testing MONTHS OF LIFE (a term often used interchangeably with “multi-disease testing”), which is testing for different conditions or diseases using the same diagnostic *Annually platform.2 Leveraging excess capacity on existing devices to enable testing Sources: UNAIDS estimates 2019; World Health across multiple diseases offers the potential to optimize limited human Organization, ‘Global Tuberculosis Report 2018’ and financial resources at health facilities, while increasing access to rapid testing services. -

Zimbabwe Rapid Response Drought 2015

Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the use of CERF funds RESIDENT / HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS ZIMBABWE RAPID RESPONSE DROUGHT 2015 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR Bishow Parajuli REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. The CERF After Action Review took place on 25 May 2016. The review brought together focal points from the following key sectors and agencies: Health and Nutrition: UNICEF and WHO, Agriculture: FAO, Food Security: WFP and WASH: UNICEF. Considering the importance of the lessons learnt element, some sectors which did not benefit from the funding did nevertheless participate in order to gain a better understanding of CERF priorities, requirements and implementation strategies. b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team and by cluster/sector coordinators as outlined in the guidelines. YES X NO Sector focal points were part of the CERF consultation from inception through to final reporting. In addition, a CERF update was a standing agenda item discussed during the monthly Humanitarian Country Team meetings. c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders as recommended in the guidelines (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant government counterparts)? YES X NO All -

Structure and Condition of Zambezi Valley Dry Forests and Thickets

SSTTRRUUCCTTUURREE AANNDD CCOONNDDIITTIIOONN OOFF ZZAAMMBBEEZZII VVAALLLLEEYY DDRRYY FFOORREESSTTSS AANNDD TTHHIICCKKEETTSS January 2002 Published by The Zambezi Society STRUCTURE AND CONDITION OF ZAMBEZI VALLEY DRY FORESTS AND THICKETS by R.E. Hoare, E.F. Robertson & K.M. Dunham January 2002 Published by The Zambezi Society The Zambezi Society is a non- The Zambezi Society P O Box HG774 governmental membership Highlands agency devoted to the Harare conservation of biodiversity Zimbabwe and wilderness and the Tel: (+263-4) 747002/3/4/5 sustainable use of natural E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.zamsoc.org resources in the Zambezi Basin Zambezi Valley dry forest biodiversity i This report has a series of complex relationships with other work carried out by The Zambezi Society. Firstly, it forms an important part of the research carried out by the Society in connection with the management of elephants and their habitats in the Guruve and Muzarabani districts of Zimbabwe, and the Magoe district of Mozambique. It therefore has implications, not only for natural resource management in these districts, but also for the transboundary management of these resources. Secondly, it relates closely to the work being carried out by the Society and the Biodiversity Foundation for Africa on the identification of community-based mechanisms FOREWORD for the conservation of biodiversity in settled lands. Thirdly, it represents a critically important contribution to the Zambezi Basin Initiative for Biodiversity Conservation (ZBI), a collaboration between the Society, the Biodiversity Foundation for Africa, and Fauna & Flora International. The ZBI is founded on the acquisition and dissemination of good biodiversity information for incorporation into developmental and other planning initiatives. -

Zimbabwe Annual Budget Review for 2016 and the 2017 Outlook

ZIMBABWE ANNUAL BUDGET REVIEW FOR 2016 AND THE 2017 OUTLOOK Presented to the Parliament of Zimbabwe on Thursday, July 20, 2017 by The Hon. P. A. Chinamasa, M.P. Minister of Finance and Economic Development 1 1 2 FOREWORD In presenting the 2017 National Budget on 8 December 2016, I indicated the need to strengthen the outline of the Budget Statement presentation as an instrument of Budget accountability and fiscal transparency, in the process improving policy engagement and accessibility for a wider range of public and targeted audiences. Accordingly, I presented a streamlined Budget Statement, and advised that extensive economic review material, which historically was presented as part of the National Budget Statement, would now be provided through a new publication called the Annual Budget Review. I am, therefore, pleased to unveil and Table the first Annual Budget Review, beginning with Fiscal Year 2016. This reports on revenue and expenditure outturn for the full fiscal year, 2016. Furthermore, the Annual Budget Review also allows opportunity for reporting on other recent macro-economic developments and the outlook for 2017. As I indicated to Parliament in December 2016, the issuance of the Annual Budget Review, therefore, makes the issuance of the Mid-Term Fiscal Policy Review no longer necessary, save for exceptional circumstances requiring Supplementary Budget proposals. 3 Treasury will, however, continue to provide Quarterly Treasury Bulletins, capturing quarterly macro-economic and fiscal developments, in addition to the Consolidated Monthly Financial Statements published monthly in line with the Public Finance Management Act. This should avail the public with necessary information on relevant economic developments, that way enhancing and supporting their decision making processes, activities and engagement with Government on overall economic policy issues. -

Fire Report 2014

ANNUAL FIRE REPORT 2014 FIRE Hay bailing along the Victoria Falls- Kazungula Road to reduce road side fires Page 1 of 24 ANNUAL FIRE REPORT 2014 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Fire Prediction Modelling ..................................................................................................................... 3 3.0 Fire Monitoring .................................................................................................................................... 7 4.0 Environmental Education and Training ................................................................................................ 8 5.0 EMA/ZRP Fire Management Awards ................................................................................................. 14 6.0 Law enforcement ............................................................................................................................... 17 7.0 Impacts of Fires .................................................................................................................................. 18 7.0 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................................... 21 8.0 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................. 22 Annex 1: Pictures .................................................................................................................................... -

“Operation Murambatsvina”

AN IN -DEPTH STUDY ON THE IMPACT OF OPERATION MUR AMBATSVINA/RESTORE ORDER IN ZIMBABWE “Primum non Nocere”: The traumatic consequences of “Operation Murambatsvina”. ActionAid International in collaboration with the Counselling Services Unit (CSU), Combined Harare Residents’ Association (CHRA) and the Zimbabwe Peace Project (ZPP) Novemberi 2005 PREFACE The right to govern is premised upon the duty to protect the governed: governments are elected to provide for the security of their citizens, that is, to promote and protect the physical and livelihood security of their citizens. In return for such security the citizens agree to surrender the powers to govern themselves by electing representatives to govern them. This is the moral contract between those who govern and those who are governed. For any government to knowingly and deliberately undermine the security of its citizens is a breach of this contract and the principle of democracy. Indeed, it removes the very foundation upon which the legitimacy of government is based. Just as there is an injunction upon health workers not to harm their patients - ‘primum non nocere”, “first do no harm” - so there must be an injunction upon governments that they ensure that any action that they take or policy that they implement will not be harmful. This is the very reason why there was formed in 2001 the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty of the United Nations promulgating the “Responsibility to Protect”: States have an obligation to protect their citizens, and the international community has an obligation to intervene when it is evident that a state cannot or will not protect its people. -

Grant Assistance for Grassroots Human Projects in Zimbabwe

Grant Assistance for Grassroots Human Projects in Zimbabwe Amount Amount No Year Project Title Implementing Organisation District (US) (yen) 1 1989 Mbungu Primary School Development Project Mbungu Primary School Gokwe 16,807 2,067,261 2 1989 Sewing and Knitting Project Rutowa Young Women's Club Gutu 5,434 668,382 3 1990 Children's Agricultural Project Save the Children USA Nyangombe 8,659 1,177,624 Mbungo Uniform Clothing Tailoring Workshop 4 1990 Mbungo Women's Club Masvingo 14,767 2,008,312 Project Construction of Gardening Facilities in 5 1991 Cold Comfort Farm Trust Harare 42,103 5,431,287 Support of Small-Scale Farmers 6 1991 Pre-School Project Kwayedza Cooperative Gweru 33,226 4,286,154 Committee for the Rural Technical 7 1992 Rural Technical Training Project Murehwa 38,266 4,936,314 Training Project 8 1992 Mukotosi Schools Project Mukotosi Project Committee Chivi 20,912 2,697,648 9 1992 Bvute Dam Project Bvute Dam Project Committee Chivi 3,558 458,982 10 1992 Uranda Clinic Project Uranda Clinic Project Committee Chivi 1,309 168,861 11 1992 Utete Dam Project Utete Dam Project Committee Chivi 8,051 1,038,579 Drilling of Ten Boreholes for Water and 12 1993 Irrigation in the Inyathi and Tsholotsho Help Age Zimbabwe Tsholotsho 41,574 5,072,028 PromotionDistricts of ofSocialForestry Matabeleland andManagement Zimbabwe National Conservation 13 1993 Buhera 46,682 5,695,204 ofWoodlands inCommunalAreas ofZimbabwe Trust Expansion of St. Mary's Gavhunga Primary St. Mary's Gavhunga Primary 14 1994 Kadoma 29,916 3,171,096 School School Tsitshatshawa -

For Human Dignity

ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION For Human Dignity REPORT ON: APRIL 2020 i DISTRIBUTED BY VERITAS e-mail: [email protected]; website: www.veritaszim.net Veritas makes every effort to ensure the provision of reliable information, but cannot take legal responsibility for information supplied. NATIONAL INQUIRY REPORT NATIONAL INQUIRY REPORT ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION For Human Dignity For Human Dignity TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................. vii ACRONYMS.................................................................................................................................................... ix GLOSSARY OF TERMS .................................................................................................................................. xi PART A: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL INQUIRY PROCESS ................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Establishment of the National Inquiry and its Terms of Reference ....................................................... 2 1.2 Methodology ..................................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 2: THE NATIONAL INQUIRY PROCESS ......................................................................................... -

Zimbabwe.Beef.20190321.Approved V2

Value Chain Analysis for Development (VCA4D) is a tool funded by the European Commission / DEVCO and is implemented in partnership with Agrinatura. Agrinatura (http://agrinatura-eu.eu) is the European AllianCe of Universities and Research Centers involved in agricultural researCh and CapaCity building for development. The information and knowledge produCed through the value Chain studies are intended to support the Delegations of the European Union and their partners in improving poliCy dialogue, investing in value Chains and better understanding the Changes linked to their aCtions VCA4D uses a systematiC methodologiCal framework for analysing value Chains in agriCulture, livestoCk, fishery, aquaCulture and agroforestry. More information inCluding reports and communication material Can be found at: https://europa.eu/CapaCity4dev/value-chain-analysis-for- development-vca4d- Team Composition Ben Bennett, Team Leader and eConomist (NRI) Muriel Figué, social expert (CIRAD) Mathieu Vigne, environmental expert (CIRAD) Charles Chakoma, national consultant (independent) Pamela KatiC, support to economist (NRI) The report was produCed through the finanCial support of the European Union. Its content is the sole responsibility of its authors and does not neCessarily refleCt the views of the European Union. The report has been realised within a projeCt finanCed by the European Union (VCA4D CTR 2016/375-804). Citation of this report: Bennett, B., Chakoma, C., Figué, M, Vigne, M., KatiC, P.; 2019. Beef Value Chain Analysis in Zimbabwe. Report for the -

ANALYSIS of SPATIAL PATTERNS of SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, and WELFARE INEQUALITY in ZIMBABWE 1 Analysis of Spatial

ANALYSIS OF SPATIAL PATTERNS OF SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, AND WELFARE INEQUALITY IN ZIMBABWE 1 Analysis of Spatial Public Disclosure Authorized Patterns of Settlement, Internal Migration, and Welfare Inequality in Zimbabwe Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Rob Swinkels Therese Norman Brian Blankespoor WITH Nyasha Munditi Public Disclosure Authorized Herbert Zvirereh World Bank Group April 18, 2019 Based on ZIMSTAT data Zimbabwe District Map, 2012 Zimbabwe Altitude Map ii ANALYSIS OF SPATIAL PATTERNS OF SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, AND WELFARE INEQUALITY IN ZIMBABWE TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii ABSTRACT v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ix ABBREVIATIONS xv 1. INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES 1 2. SPATIAL ELEMENTS OF SETTLEMENT: WHERE DID PEOPLE LIVE IN 2012? 9 3. RECENT POPULATION MOVEMENTS 27 4. REASONS BEHIND THE SPATIAL SETTLEMENT PATTERN AND POPULATION MOVEMENTS 39 5. CONSEQUENCES OF THE POPULATION’S SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION 53 6. POLICY DISCUSSION 71 AREAS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH 81 REFERENCES 83 APPENDIX A. SUPPLEMENTAL MAPS AND CHARTS 87 APPENDIX B. RESULTS OF REGRESSION ANALYSIS 99 APPENDIX C. EXAMPLE OF LOCAL DEVELOPMENT INDEX 111 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by a team led by Rob Swinkels, comprising Therese Norman and Brian Blankespoor. Important background work was conducted by Nyasha Munditi and Herbert Zvirereh. Wishy Chipiro provided valuable technical support. Overall guidance was provided by Andrew Dabalen, Ruth Hill, and Mukami Kariuki. Peer reviewers were Luc Christiaensen, Nagaraja Rao Harshadeep, Hans Hoogeveen, Kirsten Hommann, and Marko Kwaramba. Tawanda Chingozha commented on an earlier draft and shared the shapefiles of the Zimbabwe farmland use types. Yondela Silimela, Carli Bunding-Venter, Leslie Nii Odartey Mills, and Aiga Stokenberga provided inputs to the policy section. -

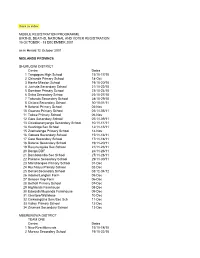

Back to Index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME

Back to index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME BIRTHS, DEATHS, NATIONAL AND VOTER REGISTRATION 15 OCTOBER - 13 DECEMBER 2001 as in Herald 12 October 2001 MIDLANDS PROVINCE SHURUGWI DISTRICT Centre Dates 1 Tongogara High School 15/10-17/10 2 Chironde Primary School 18-Oct 3 Hanke Mission School 19/10-20/10 4 Juchuta Secondary School 21/10-22/10 5 Dombwe Primary School 23/10-24/10 6 Svika Secondary Schoo 25/10-27/10 7 Takunda Secondary School 28/10-29/10 8 Chitora Secondary School 30/10-01/11 9 Batanai Primary School 02-Nov 10 Gwanza Primary School 03/11-05/11 11 Tokwe Primary School 06-Nov 12 Gare Secondary School 07/11-09/11 13 Chivakanenyanga Secondary School 10/11-11/11 14 Kushinga Sec School 12/11-13/11 15 Zvamatenga Primary School 14-Nov 16 Gamwa Secondary School 15/11-16/11 17 Gato Secondary School 17/11-18/11 18 Batanai Secondary School 19/11-20/11 19 Rusununguko Sec School 21/11-23/11 20 Donga DDF 24/11-26/11 21 Dombotombo Sec School 27/11-28/11 22 Pakame Secondary School 29/11-30/11 23 Marishongwe Primary School 01-Dec 24 Ruchanyu Primary School 02-Dec 25 Dorset Secondary School 03/12-04/12 26 Adams/Longton Farm 05-Dec 27 Beacon Kop Farm 06-Dec 28 Bethall Primary School 07-Dec 29 Highlands Farmhouse 08-Dec 30 Edwards/Muponda Farmhouse 09-Dec 31 Glentore/Wallclose 10-Dec 32 Chikwingizha Sem/Sec Sch 11-Dec 33 Valley Primary School 12-Dec 34 Zvumwa Secondary School 13-Dec MBERENGWA DISTRICT TEAM ONE Centre Dates 1 New Resettlements 15/10-18/10 2 Murezu Secondary School 19/10-22/10 3 Chizungu Secondary School 23/10-26/10 4 Matobo Secondary