Activation of Sphingosine Kinase 1 by ERK1/2Mediated Phosphorylation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B Activin a Receptor, Type IB

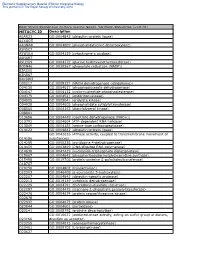

Table S1. Kinase clones included in human kinase cDNA library for yeast two-hybrid screening Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B activin A receptor, type IB ADCK2 aarF domain containing kinase 2 ADCK4 aarF domain containing kinase 4 AGK multiple substrate lipid kinase;MULK AK1 adenylate kinase 1 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 like 1 AK3L1 adenylate kinase 3 ALDH18A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1;ALDH18A1 ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) ALPK1 alpha-kinase 1 ALPK2 alpha-kinase 2 AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II ARAF v-raf murine sarcoma 3611 viral oncogene homolog 1 ARSG arylsulfatase G;ARSG AURKB aurora kinase B AURKC aurora kinase C BCKDK branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase BMPR1A bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA BMPR2 bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) BRAF v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 BRD4 bromodomain containing 4 BTK Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase BUB1 BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog (yeast) BUB1B BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog beta (yeast) C9orf98 chromosome 9 open reading frame 98;C9orf98 CABC1 chaperone, ABC1 activity of bc1 complex like (S. pombe) CALM1 calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM2 calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM3 calmodulin 3 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CAMK1 calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I CAMK2A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II alpha CAMK2B calcium/calmodulin-dependent -

Supplementary Materials

1 Supplementary Materials: Supplemental Figure 1. Gene expression profiles of kidneys in the Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice. (A) A heat map of microarray data show the genes that significantly changed up to 2 fold compared between Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice (N=4 mice per group; p<0.05). Data show in log2 (sample/wild-type). 2 Supplemental Figure 2. Sting signaling is essential for immuno-phenotypes of the Fcgr2b-/-lupus mice. (A-C) Flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes isolated from wild-type, Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice at the age of 6-7 months (N= 13-14 per group). Data shown in the percentage of (A) CD4+ ICOS+ cells, (B) B220+ I-Ab+ cells and (C) CD138+ cells. Data show as mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001). 3 Supplemental Figure 3. Phenotypes of Sting activated dendritic cells. (A) Representative of western blot analysis from immunoprecipitation with Sting of Fcgr2b-/- mice (N= 4). The band was shown in STING protein of activated BMDC with DMXAA at 0, 3 and 6 hr. and phosphorylation of STING at Ser357. (B) Mass spectra of phosphorylation of STING at Ser357 of activated BMDC from Fcgr2b-/- mice after stimulated with DMXAA for 3 hour and followed by immunoprecipitation with STING. (C) Sting-activated BMDC were co-cultured with LYN inhibitor PP2 and analyzed by flow cytometry, which showed the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IAb expressing DC (N = 3 mice per group). 4 Supplemental Table 1. Lists of up and down of regulated proteins Accession No. -

Lipid Metabolic Reprogramming: Role in Melanoma Progression and Therapeutic Perspectives

cancers Review Lipid metabolic Reprogramming: Role in Melanoma Progression and Therapeutic Perspectives 1, 1, 1 2 1 Laurence Pellerin y, Lorry Carrié y , Carine Dufau , Laurence Nieto , Bruno Ségui , 1,3 1, , 1, , Thierry Levade , Joëlle Riond * z and Nathalie Andrieu-Abadie * z 1 Centre de Recherches en Cancérologie de Toulouse, Equipe Labellisée Fondation ARC, Université Fédérale de Toulouse Midi-Pyrénées, Université Toulouse III Paul-Sabatier, Inserm 1037, 2 avenue Hubert Curien, tgrCS 53717, 31037 Toulouse CEDEX 1, France; [email protected] (L.P.); [email protected] (L.C.); [email protected] (C.D.); [email protected] (B.S.); [email protected] (T.L.) 2 Institut de Pharmacologie et de Biologie Structurale, CNRS, Université Toulouse III Paul-Sabatier, UMR 5089, 205 Route de Narbonne, 31400 Toulouse, France; [email protected] 3 Laboratoire de Biochimie Métabolique, CHU Toulouse, 31059 Toulouse, France * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.R.); [email protected] (N.A.-A.); Tel.: +33-582-7416-20 (J.R.) These authors contributed equally to this work. y These authors jointly supervised this work. z Received: 15 September 2020; Accepted: 23 October 2020; Published: 27 October 2020 Simple Summary: Melanoma is a devastating skin cancer characterized by an impressive metabolic plasticity. Melanoma cells are able to adapt to the tumor microenvironment by using a variety of fuels that contribute to tumor growth and progression. In this review, the authors summarize the contribution of the lipid metabolic network in melanoma plasticity and aggressiveness, with a particular attention to specific lipid classes such as glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, sterols and eicosanoids. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Building a Metabolic Bridge Between Glycolysis and Sphingolipid Biosynthesis : Implications in Cancer

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2014 Building a metabolic bridge between glycolysis and sphingolipid biosynthesis : implications in cancer. Morgan L. Stathem University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Stathem, Morgan L., "Building a metabolic bridge between glycolysis and sphingolipid biosynthesis : implications in cancer." (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1374. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1374 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUILDING A METABOLIC BRIDGE BETWEEN GLYCOLYSIS AND SPHINGOLIPID BIOSYNTHESIS: IMPLICATIONS IN CANCER By Morgan L. Stathem B.S., University of Georgia, 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Medicine of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology University of Louisville Louisville, KY August 2014 BUILDING A METABOLIC BRIDGE BETWEEN GLYCOLYSIS AND SPHINGOLIPID BIOSYNTHESIS: IMPLICATIONS IN CANCER By Morgan L. Stathem B.S., University of Georgia, 2010 Thesis Approved on 08/07/2014 by the following Thesis Committee: __________________________________ Leah Siskind, Ph.D. __________________________________ Levi Beverly, Ph.D. -

Targeting the Sphingosine Kinase/Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Signaling Axis in Drug Discovery for Cancer Therapy

cancers Review Targeting the Sphingosine Kinase/Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Signaling Axis in Drug Discovery for Cancer Therapy Preeti Gupta 1, Aaliya Taiyab 1 , Afzal Hussain 2, Mohamed F. Alajmi 2, Asimul Islam 1 and Md. Imtaiyaz Hassan 1,* 1 Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Basic Sciences, Jamia Millia Islamia, Jamia Nagar, New Delhi 110025, India; [email protected] (P.G.); [email protected] (A.T.); [email protected] (A.I.) 2 Department of Pharmacognosy, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia; afi[email protected] (A.H.); [email protected] (M.F.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Cancer is the prime cause of death globally. The altered stimulation of signaling pathways controlled by human kinases has often been observed in various human malignancies. The over-expression of SphK1 (a lipid kinase) and its metabolite S1P have been observed in various types of cancer and metabolic disorders, making it a potential therapeutic target. Here, we discuss the sphingolipid metabolism along with the critical enzymes involved in the pathway. The review provides comprehensive details of SphK isoforms, including their functional role, activation, and involvement in various human malignancies. An overview of different SphK inhibitors at different phases of clinical trials and can potentially be utilized as cancer therapeutics has also been reviewed. Citation: Gupta, P.; Taiyab, A.; Hussain, A.; Alajmi, M.F.; Islam, A.; Abstract: Sphingolipid metabolites have emerged as critical players in the regulation of various Hassan, M..I. Targeting the Sphingosine Kinase/Sphingosine- physiological processes. Ceramide and sphingosine induce cell growth arrest and apoptosis, whereas 1-Phosphate Signaling Axis in Drug sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) promotes cell proliferation and survival. -

Generated by SRI International Pathway Tools Version 25.0, Authors S

Authors: Pallavi Subhraveti Peter D Karp Ingrid Keseler An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Anamika Kothari Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. Gcf_000442315Cyc: Rubellimicrobium thermophilum DSM 16684 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. Ron Caspi lipid II (meso phosphate diaminopimelate sn-glycerol containing) phosphate dCTP 3-phosphate predicted ABC RS07495 RS12165 RS03605 transporter RS13105 of phosphate lipid II (meso dCTP sn-glycerol diaminopimelate phosphate 3-phosphate containing) phosphate Secondary Metabolite Degradation Storage Compound Biosynthesis Tetrapyrrole Biosynthesis Hormone Biosynthesis Aromatic Compound Aldehyde Degradation UDP-N-acetyl- Biosynthesis undecaprenyl- a mature (4R)-4-hydroxy- an L-glutamyl- a [protein]-L- queuosine at Macromolecule Modification myo-inositol degradation I α-D-glucosamine adenosylcobinamide a purine L-canavanine 5'-deoxyadenosine sec Metabolic Regulator Biosynthesis Amine and Polyamine Biosynthesis polyhydroxybutanoate biosynthesis siroheme biosynthesis methylglyoxal degradation I diphospho-N- peptidoglycan 2-oxoglutarate Gln β-isoaspartate glu position 34 ser a tRNA indole-3-acetate -

Kinase-Targeted Cancer Therapies: Progress, Challenges and Future Directions Khushwant S

Bhullar et al. Molecular Cancer (2018) 17:48 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-018-0804-2 REVIEW Open Access Kinase-targeted cancer therapies: progress, challenges and future directions Khushwant S. Bhullar1, Naiara Orrego Lagarón2, Eileen M. McGowan3, Indu Parmar4, Amitabh Jha5, Basil P. Hubbard1 and H. P. Vasantha Rupasinghe6,7* Abstract The human genome encodes 538 protein kinases that transfer a γ-phosphate group from ATP to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues. Many of these kinases are associated with human cancer initiation and progression. The recent development of small-molecule kinase inhibitors for the treatment of diverse types of cancer has proven successful in clinical therapy. Significantly, protein kinases are the second most targeted group of drug targets, after the G-protein- coupled receptors. Since the development of the first protein kinase inhibitor, in the early 1980s, 37 kinase inhibitors have received FDA approval for treatment of malignancies such as breast and lung cancer. Furthermore, about 150 kinase-targeted drugs are in clinical phase trials, and many kinase-specific inhibitors are in the preclinical stage of drug development. Nevertheless, many factors confound the clinical efficacy of these molecules. Specific tumor genetics, tumor microenvironment, drug resistance, and pharmacogenomics determine how useful a compound will be in the treatment of a given cancer. This review provides an overview of kinase-targeted drug discovery and development in relation to oncology and highlights the challenges and future potential for kinase-targeted cancer therapies. Keywords: Kinases, Kinase inhibition, Small-molecule drugs, Cancer, Oncology Background Recent advances in our understanding of the fundamen- Kinases are enzymes that transfer a phosphate group to a tal molecular mechanisms underlying cancer cell signaling protein while phosphatases remove a phosphate group have elucidated a crucial role for kinases in the carcino- from protein. -

The Effects of Bone Marrow Adipocytes on Metabolic Regulation in Metastatic Prostate Cancer" (2017)

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2017 The ffecE ts Of Bone Marrow Adipocytes On Metabolic Regulation In Metastatic Prostate Cancer Jonathan Diedrich Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Oncology Commons Recommended Citation Diedrich, Jonathan, "The Effects Of Bone Marrow Adipocytes On Metabolic Regulation In Metastatic Prostate Cancer" (2017). Wayne State University Dissertations. 1797. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/1797 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE EFFECTS OF BONE MARROW ADIPOCYTES ON METASTATIC PROSTATE CANCER CELL METABOLISM AND SIGNALLING by JONATHAN DRISCOLL DIEDRICH DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2017 MAJOR: CANCER BIOLOGY Approved By: Advisor Date © COPYRIGHT BY JONATHAN DIEDRICH 2017 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my Family, Friends, and Wally ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS When I joined the Podgorski laboratory in April of 2014, I had finished my rotations and spent some time in a collaborating laboratory honing my technical and creative thinking skills to become a valuable asset to her team; however, I was still unprepared for the exciting journey it would be through Izabela’s laboratory over the last three years. I was extremely lucky to have landed in Dr. Podgorski’s laboratory and will be forever thankful for the tremendous support she has given me to aid in my development as an independent investigator. -

Intracellular Sphingosine Releases Calcium from Lysosomes

RESEARCH ARTICLE Intracellular sphingosine releases calcium from lysosomes Doris Ho¨ glinger1, Per Haberkant1, Auxiliadora Aguilera-Romero2, Howard Riezman2, Forbes D Porter3, Frances M Platt4, Antony Galione4, Carsten Schultz1* 1Cell Biology and Biophysics Unit, European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Heidelberg, Germany; 2Department of Biochemistry, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland; 3Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, United States; 4Department of Pharmacology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom Abstract To elucidate new functions of sphingosine (Sph), we demonstrate that the spontaneous elevation of intracellular Sph levels via caged Sph leads to a significant and transient calcium release from acidic stores that is independent of sphingosine 1-phosphate, extracellular and ER calcium levels. This photo-induced Sph-driven calcium release requires the two-pore channel 1 (TPC1) residing on endosomes and lysosomes. Further, uncaging of Sph leads to the translocation of the autophagy-relevant transcription factor EB (TFEB) to the nucleus specifically after lysosomal calcium release. We confirm that Sph accumulates in late endosomes and lysosomes of cells derived from Niemann-Pick disease type C (NPC) patients and demonstrate a greatly reduced calcium release upon Sph uncaging. We conclude that sphingosine is a positive regulator of calcium release from acidic stores and that understanding the interplay between Sph homeostasis, calcium -

An Entirely Specific Type I A-Kinase Anchoring Protein That Can

An entirely specific type I A-kinase anchoring PNAS PLUS protein that can sequester two molecules of protein kinase A at mitochondria Christopher K. Meansa, Birgitte Lygrenb, Lorene K. Langeberga, Ankur Jainc, Rose E. Dixond, Amanda L. Vegad, Matthew G. Golda, Susanna Petrosyane, Susan S. Taylorf, Anne N. Murphye, Taekjip Hac,g, Luis F. Santanad, Kjetil Taskenb, and John D. Scotta,1 aHoward Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Pharmacology, University of Washington School of Medicine, 1959 Pacific Avenue NE, Seattle, WA 98195; bBiotechnology Center of Oslo and Center for Molecular Medicine Norway, Nordic European Molecular Biology Laboratory Partnership, University of Oslo, N-0317 Oslo, Norway; cCenter for Biophysics and Computational Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61822; dDepartment of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195; eDepartment of Pharmacology, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093; fHoward Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093; and gHoward Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Physics and Center for the Physics of Living Cells, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61822 Edited by* Joseph A. Beavo, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, and approved October 5, 2011 (received for review May 6, 2011) A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) tether the cAMP-dependent Two C subunit genes encode the ubiquitously expressed Cα and protein kinase (PKA) to intracellular sites where they preferentially Cβ isoforms (14). The four R subunit genes are subdivided into phosphorylate target substrates. Most AKAPs exhibit nanomolar two classes: type I [RI (RIα and RIβ)] and type II [RII (RIIα and affinity for the regulatory (RII) subunit of the type II PKA holoen- RIIβ)] (15–17).