Lipid Metabolic Reprogramming: Role in Melanoma Progression and Therapeutic Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"This Is the Peer Reviewed Version of the Following Article: Murray, M., Dyari, H

"This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Murray, M., Dyari, H. R. E., Allison, S. E. and Rawling, T. (2014), Lipid analogues as potential drugs for the regulation of mitochondrial cell death. British Journal of Pharmacology, 171: 2051–2066. doi: 10.1111/bph.12417 which has been published in final form at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.12417/abstract;jsessionid= 1A6A774DBD2AA9859B823125976041F6.f03t01 . This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving." 1 Revised manuscript 2013-BJP-0609-RCT-G Lipid analogues as potential drugs for the regulation of mitochondrial cell death Michael Murray1, Herryawan Ryadi Eziwar Dyari1, Sarah E. Allison1 and Tristan Rawling2 1Pharmacogenomics and Drug Development Group, Discipline of Pharmacology, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia, and 2School of Pharmacy, Graduate School of Health, University of Technology, Sydney, PO Box 123, Broadway NSW 2007, Australia. Address for correspondence: Dr Michael Murray Pharmacogenomics and Drug Development Group, Discipline of Pharmacology, Medical Foundation Building, Room 105, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Tel: (61-2-9036-3259) Fax (61-2-9036-3244) Email: [email protected] Running title: Lipids drugs to target mitochondrial cell death 2 Abstract The mitochondrion has fundamental roles in the production of energy as ATP, the regulation of cell viability and apoptosis, and the biosynthesis of major structural and regulatory molecules, such as lipids. During ATP production reactive oxygen species are generated that alter the intracellular redox state and activate apoptosis. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a well recognized component of the pathogenesis of diseases such as cancer. -

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B Activin a Receptor, Type IB

Table S1. Kinase clones included in human kinase cDNA library for yeast two-hybrid screening Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B activin A receptor, type IB ADCK2 aarF domain containing kinase 2 ADCK4 aarF domain containing kinase 4 AGK multiple substrate lipid kinase;MULK AK1 adenylate kinase 1 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 like 1 AK3L1 adenylate kinase 3 ALDH18A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1;ALDH18A1 ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) ALPK1 alpha-kinase 1 ALPK2 alpha-kinase 2 AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II ARAF v-raf murine sarcoma 3611 viral oncogene homolog 1 ARSG arylsulfatase G;ARSG AURKB aurora kinase B AURKC aurora kinase C BCKDK branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase BMPR1A bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA BMPR2 bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) BRAF v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 BRD4 bromodomain containing 4 BTK Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase BUB1 BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog (yeast) BUB1B BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog beta (yeast) C9orf98 chromosome 9 open reading frame 98;C9orf98 CABC1 chaperone, ABC1 activity of bc1 complex like (S. pombe) CALM1 calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM2 calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM3 calmodulin 3 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CAMK1 calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I CAMK2A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II alpha CAMK2B calcium/calmodulin-dependent -

Diapositiva 1

ns 10 A Unmethylated C Methylated ) 8 Normal Normal Tissue Cervix Esophagus 4 cervical esophageal a.u. * *** * *** ( 6 TargetID MAPINFO Position Ca-Ski HeLa SW756 tissue COLO-680N KYSE-180 OACM 5.1C tissue cg04255070 22851591 TSS1500 0.896 0.070 0.082 0.060 0.613 0.622 0.075 0.020 2 (log2) 4 cg01593340 22851587 TSS1500 0.826 0.055 0.051 0.110 0.518 0.518 0.034 0.040 cg16113692 22851502 TSS200 0.964 0.073 0.072 0.030 0.625 0.785 0.018 0.010 2 0 cg26918510 22851422 TSS200 0.985 0.019 0.000 0.000 0.711 0.961 0.010 0.060 expression cg26821579 22851416 TSS200 0.988 0.083 0.058 0.000 0.387 0.955 0.021 0.050 TRMT12 mRNA Expression mRNA TRMT12 0 cg01129966 22851401 TSS200 0.933 0.039 0.077 0.020 0.815 0.963 0.078 0.010 -2 cg25421615 22851383 TSS200 0.958 0.033 0.006 0.000 0.447 0.971 0.037 0.020 mRNA cg17953636 22851321 1stExon 0.816 0.092 0.099 0.080 0.889 0.750 0.136 0.030 -4 Methylated SVIP Unmethylated SVIP relative expression (a.u.) expression relative SVIP D Cervix Esophagus HNC Meth ) HNC Unmeth Cervix Meth 3.0 *** Cervix Unmeth *** Esophagus Meth a.u. ( 2.5 CaCaEsophagus-Ski-Ski Unmeth COLO-680N Haematological Meth TSS B TSS Haematological Unmeth 2.0 -244 bp +104 bp 244 bp +104 bp 1.5 ** * expression -SVIP 1.0 HeLa KYSE-180 HeLa TSS TSS 0.5 -ACTB 244 bp +104 bp - 244 bp +104 bp mRNA 0.0 HeLa SW756 Ca-Ski SW756 SW756 OACM 5.1C TSS KYSE-180 TSS COLO-680NOACM 5.1 C - 244 bp +104 bp 244 bp +104 bp E ) 3.0 * Ca-Ski COLO-680N WT TSS TSS 2.0 a.u. -

Altered Expression and Function of Mitochondrial Я-Oxidation Enzymes

0031-3998/01/5001-0083 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 50, No. 1, 2001 Copyright © 2001 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Printed in U.S.A. Altered Expression and Function of Mitochondrial -Oxidation Enzymes in Juvenile Intrauterine-Growth-Retarded Rat Skeletal Muscle ROBERT H. LANE, DAVID E. KELLEY, VLADIMIR H. RITOV, ANNA E. TSIRKA, AND ELISA M. GRUETZMACHER Department of Pediatrics, UCLA School of Medicine, Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA, Los Angeles, California 90095, U.S.A. [R.H.L.]; and Departments of Internal Medicine [D.E.K., V.H.R.] and Pediatrics [R.H.L., A.E.T., E.M.G.], University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Magee-Womens Research Institute, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Uteroplacental insufficiency and subsequent intrauterine creased in IUGR skeletal muscle mitochondria, and isocitrate growth retardation (IUGR) affects postnatal metabolism. In ju- dehydrogenase activity was unchanged. Interestingly, skeletal venile rats, IUGR alters skeletal muscle mitochondrial gene muscle triglycerides were significantly increased in IUGR skel- expression and reduces mitochondrial NADϩ/NADH ratios, both etal muscle. We conclude that uteroplacental insufficiency alters of which affect -oxidation flux. We therefore hypothesized that IUGR skeletal muscle mitochondrial lipid metabolism, and we gene expression and function of mitochondrial -oxidation en- speculate that the changes observed in this study play a role in zymes would be altered in juvenile IUGR skeletal muscle. To test the long-term morbidity associated with IUGR. (Pediatr Res 50: this hypothesis, mRNA levels of five key mitochondrial enzymes 83–90, 2001) (carnitine palmitoyltransferase I, trifunctional protein of -oxi- dation, uncoupling protein-3, isocitrate dehydrogenase, and mi- Abbreviations tochondrial malate dehydrogenase) and intramuscular triglycer- CPTI, carnitine palmitoyltransferase I ides were quantified in 21-d-old (preweaning) IUGR and control IUGR, intrauterine growth retardation rat skeletal muscle. -

Upregulation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Α And

Upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and the lipid metabolism pathway promotes carcinogenesis of ampullary cancer Chih-Yang Wang, Ying-Jui Chao, Yi-Ling Chen, Tzu-Wen Wang, Nam Nhut Phan, Hui-Ping Hsu, Yan-Shen Shan, Ming-Derg Lai 1 Supplementary Table 1. Demographics and clinical outcomes of five patients with ampullary cancer Time of Tumor Time to Age Differentia survival/ Sex Staging size Morphology Recurrence recurrence Condition (years) tion expired (cm) (months) (months) T2N0, 51 F 211 Polypoid Unknown No -- Survived 193 stage Ib T2N0, 2.41.5 58 F Mixed Good Yes 14 Expired 17 stage Ib 0.6 T3N0, 4.53.5 68 M Polypoid Good No -- Survived 162 stage IIA 1.2 T3N0, 66 M 110.8 Ulcerative Good Yes 64 Expired 227 stage IIA T3N0, 60 M 21.81 Mixed Moderate Yes 5.6 Expired 16.7 stage IIA 2 Supplementary Table 2. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of an ampullary cancer microarray using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID). This table contains only pathways with p values that ranged 0.0001~0.05. KEGG Pathway p value Genes Pentose and 1.50E-04 UGT1A6, CRYL1, UGT1A8, AKR1B1, UGT2B11, UGT2A3, glucuronate UGT2B10, UGT2B7, XYLB interconversions Drug metabolism 1.63E-04 CYP3A4, XDH, UGT1A6, CYP3A5, CES2, CYP3A7, UGT1A8, NAT2, UGT2B11, DPYD, UGT2A3, UGT2B10, UGT2B7 Maturity-onset 2.43E-04 HNF1A, HNF4A, SLC2A2, PKLR, NEUROD1, HNF4G, diabetes of the PDX1, NR5A2, NKX2-2 young Starch and sucrose 6.03E-04 GBA3, UGT1A6, G6PC, UGT1A8, ENPP3, MGAM, SI, metabolism -

Stimulating the Expression of Sphingosine Kinase 1 (Sphk1) Is Bene�Cial to Reduce Acrylamide-Induced Nerve Cell Damage

Stimulating the Expression of Sphingosine Kinase 1 (SphK1) is Benecial to Reduce Acrylamide-Induced Nerve Cell Damage Yong-Hui Wu ( [email protected] ) Harbin Medical University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4838-2947 Sheng-Yuan Wang Harbin Medical University Xiao-Li Wang Harbin Medical University Rui Xin Harbin Medical University Ye Xin Harbin Medical University Rui Wang Harbin Medical University Kun Ma Harbin Medical University Cui-Ping Yu Harbin Medical University Dan Zhang Harbin Medical University Xiao-Rong Zhou Harbin Medical University Wei-Wei Ma Harbin Medical University Chao Wang Harbin Medical University Research Keywords: Acrylamide, SphKl, Neurotoxicity, Apoptosis, MAPK pathway Posted Date: September 28th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-80914/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Stimulating the expression of sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1) is beneficial to reduce acrylamide-induced nerve cell damage Sheng-Yuan Wang1, Xiao-Li Wang1, Rui Xin1, Ye Xin1, Rui Wang1, Kun Ma2, Cui-Ping Yu1, Dan Zhang1, Xiao-Rong Zhou1, Wei-Wei Ma3, Chao Wang4, Yong-Hui Wu1* 1 Department of Occupational Health, Public Health College, Harbin Medical University, Harbin, P. R. 2 Department of Hygienic Toxicology, Public Health College, Harbin Medical University, Harbin, P. R. 3 Harbin Railway Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Harbin, P. R. 4 Health Commission of Heilongjiang Province. * Address correspondence to this author at: The Department of Occupational Health, Public Health College, Harbin Medical University, 157 Baojian Road, Nan gang District, Harbin, People’s Republic of China 150086. Phone: +86-451-8750-2827, Fax: +86-451-8750-2827, E-mail: [email protected]. -

ATP-Citrate Lyase Has an Essential Role in Cytosolic Acetyl-Coa Production in Arabidopsis Beth Leann Fatland Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2002 ATP-citrate lyase has an essential role in cytosolic acetyl-CoA production in Arabidopsis Beth LeAnn Fatland Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Molecular Biology Commons, and the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Fatland, Beth LeAnn, "ATP-citrate lyase has an essential role in cytosolic acetyl-CoA production in Arabidopsis " (2002). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 1218. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/1218 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ATP-citrate lyase has an essential role in cytosolic acetyl-CoA production in Arabidopsis by Beth LeAnn Fatland A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Plant Physiology Program of Study Committee: Eve Syrkin Wurtele (Major Professor) James Colbert Harry Homer Basil Nikolau Martin Spalding Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2002 UMI Number: 3158393 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Supplementary Information Material and Methods

MCT-11-0474 BKM120: a potent and specific pan-PI3K inhibitor Supplementary Information Material and methods Chemicals The EGFR inhibitor NVP-AEE788 (Novartis), the Jak inhibitor I (Merck Calbiochem, #420099) and anisomycin (Alomone labs, # A-520) were prepared as 50 mM stock solutions in 100% DMSO. Doxorubicin (Adriablastin, Pfizer), EGF (Sigma Ref: E9644), PDGF (Sigma, Ref: P4306) and IL-4 (Sigma, Ref: I-4269) stock solutions were prepared as recommended by the manufacturer. For in vivo administration: Temodal (20 mg Temozolomide capsules, Essex Chemie AG, Luzern) was dissolved in 4 mL KZI/glucose (20/80, vol/vol); Taxotere was bought as 40 mg/mL solution (Sanofi Aventis, France), and prepared in KZI/glucose. Antibodies The primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-S473P-Akt (#9271), anti-T308P-Akt (#9276,), anti-S9P-GSK3β (#9336), anti-T389P-p70S6K (#9205), anti-YP/TP-Erk1/2 (#9101), anti-YP/TP-p38 (#9215), anti-YP/TP-JNK1/2 (#9101), anti-Y751P-PDGFR (#3161), anti- p21Cip1/Waf1 (#2946), anti-p27Kip1 (#2552) and anti-Ser15-p53 (#9284) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies; anti-Akt (#05-591), anti-T32P-FKHRL1 (#06-952) and anti- PDGFR (#06-495) antibodies were from Upstate; anti-IGF-1R (#SC-713) and anti-EGFR (#SC-03) antibodies were from Santa Cruz; anti-GSK3α/β (#44610), anti-Y641P-Stat6 (#611566), anti-S1981P-ATM (#200-301), anti-T2609 DNA-PKcs (#GTX24194) and anti- 1 MCT-11-0474 BKM120: a potent and specific pan-PI3K inhibitor Y1316P-IGF-1R were from Bio-Source International, Becton-Dickinson, Rockland, GenTex and internal production, respectively. The 4G10 antibody was from Millipore (#05-321MG). -

Supplementary Materials

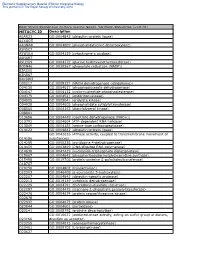

1 Supplementary Materials: Supplemental Figure 1. Gene expression profiles of kidneys in the Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice. (A) A heat map of microarray data show the genes that significantly changed up to 2 fold compared between Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice (N=4 mice per group; p<0.05). Data show in log2 (sample/wild-type). 2 Supplemental Figure 2. Sting signaling is essential for immuno-phenotypes of the Fcgr2b-/-lupus mice. (A-C) Flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes isolated from wild-type, Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice at the age of 6-7 months (N= 13-14 per group). Data shown in the percentage of (A) CD4+ ICOS+ cells, (B) B220+ I-Ab+ cells and (C) CD138+ cells. Data show as mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001). 3 Supplemental Figure 3. Phenotypes of Sting activated dendritic cells. (A) Representative of western blot analysis from immunoprecipitation with Sting of Fcgr2b-/- mice (N= 4). The band was shown in STING protein of activated BMDC with DMXAA at 0, 3 and 6 hr. and phosphorylation of STING at Ser357. (B) Mass spectra of phosphorylation of STING at Ser357 of activated BMDC from Fcgr2b-/- mice after stimulated with DMXAA for 3 hour and followed by immunoprecipitation with STING. (C) Sting-activated BMDC were co-cultured with LYN inhibitor PP2 and analyzed by flow cytometry, which showed the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IAb expressing DC (N = 3 mice per group). 4 Supplemental Table 1. Lists of up and down of regulated proteins Accession No. -

2015 Annual Meeting Abstract Supplement Late-Breaking Abstract Submissions

2015 Annual Meeting Abstract Supplement Late-Breaking Abstract Submissions All Late-Breaking Abstracts will be presented on Thursday, March 26, from 8:30 am–12:00 noon. These abstracts will be available via the mobile event app, online planner, and a downloadable PDF from the SOT website. 54th Annual Meeting and ToxExpoTM San Diego, California March 22–26, 2015 www.toxicology.org THURSDAY POSTER SESSION MAP March 2015—8:30 AM to 12:00 Noon—Sails Pavilion Poster Set Up—7:00 AM to 8:30 AM 260 259 258 257 256 301 302 303 304 305 660 659 658 657 656 251 252 253 254 255 310 309 308 307 306 651 652 653 654 655 250 249 248 247 246 311 312 313 314 315 650 649 648 647 646 241 242 243 244 245 320 319 318 317 316 641 642 643 644 645 240 239 238 237 236 321 322 323 324 325 640 639 638 637 636 231 232 233 234 235 330 329 328 327 326 631 632 633 634 635 230 229 228 227 226 331 332 333 334 335 630 629 628 627 626 221 222 223 224 225 340 339 338 337 336 621 622 623 624 625 220 219 218 217 216 341 342 343 344 345 620 619 618 617 616 211 212 213 214 215 350 349 348 347 346 611 612 613 614 615 210 209 208 207 206 351 352 353 354 355 610 609 608 607 606 201 202 203 204 205 360 359 358 357 356 601 602 603 604 605 170 169 168 167 166 401 402 403 404 405 570 569 568 567 566 161 162 163 164 165 410 409 408 407 406 561 562 563 564 565 160 159 158 157 156 411 412 413 414 415 560 559 558 557 556 151 152 153 154 155 420 419 418 417 416 551 552 553 554 555 150 149 148 147 146 421 422 423 424 425 550 549 548 547 546 141 142 143 144 145 430 429 428 427 426 541 542 -

Extracellular Adenosine Triphosphate and Adenosine in Cancer

Oncogene (2010) 29, 5346–5358 & 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9232/10 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW Extracellular adenosine triphosphate and adenosine in cancer J Stagg and MJ Smyth Cancer Immunology Program, Sir Donald and Lady Trescowthick Laboratories, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is actively released in the mulated the hypothesis of purinergic neurotransmission extracellular environment in response to tissue damage (Burnstock, 1972). Burnstock’s hypothesis that ATP and cellular stress. Through the activation of P2X and could be released by cells to perform intercellular P2Y receptors, extracellular ATP enhances tissue repair, signaling was initially met with skepticism, as it seemed promotes the recruitment of immune phagocytes and unlikely that a molecule that acts as an intracellular dendritic cells, and acts as a co-activator of NLR family, source of energy would also function as an extracellular pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes. messenger. Nevertheless, Burnstock pursued his work The conversion of extracellular ATP to adenosine, in and, together with Che Su and John Bevan, reported contrast, essentially through the enzymatic activity of the that ATP was also released from sympathetic nerves ecto-nucleotidases CD39 and CD73, acts as a negative- during stimulation (Su et al., 1971). Three decades later, feedback mechanism to prevent excessive immune responses. following the cloning and characterization of ATP and Here we review the effects of extracellular ATP and adenosine adenosine cell surface receptors, purinergic signaling is a on tumorigenesis. First, we summarize the functions of well-established concept and constitutes an expanding extracellular ATP and adenosine in the context of tumor field of research in health and disease, including cancer immunity.