Lietuvos Muzikologija 20.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

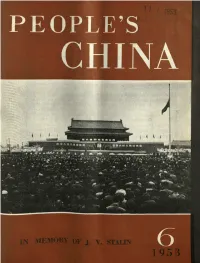

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

Sofia Gubaidulina AUSSERDEM Prokofjew, Denissow, Kantscheli, Geringas, Chatschaturjan U.A

AUSGABE 1. 2020 GEBURTS- UND GEDENKTAGE 90. GEBURTSTAG 2021 Sofia Gubaidulina AUSSERDEM Prokofjew, Denissow, Kantscheli, Geringas, Chatschaturjan u.a. INHALT / CONTENT Liebe Leserinnen, 03 / 22 liebe Leser, Sofia Gubaidulina 90. Geburtstag im Jahr 2021 die russische Komponistin Jelena Firssowa sagte ein- 06 / 24 mal über die von ihr bewunderte Sofia Gubaidulina, Georgische Musik sie sei eine „Schamanin in der Musik”, eine der tief- des 20. Jahrhunderts gründigsten und interessantesten Komponistinnen Kantscheli, Zinzadse, der Gegenwart. Im Jahr 2021 begeht Gubaidulina Nassidse ihren 90. Geburtstag. In diesem Magazin, das Kompo- nistenjubiläen der bervorstehenden Jahre 2021 und 08 / 26 2022 zum Inhalt hat, berichten wir von neuesten Sergej Prokofjew Werken Gubaidulinas und veröffentlichen zudem ein zum 130. Geburtstag dieser Komponistin gewidmetes Exklusiv-Interview 12 mit dem Dirigenten Kent Nagano. 100. Geburtstage von Francisco Tanzer & Stanisław Lem Ein weiteres Jubiläum steht uns mit Sergej Prokof- jews 130. Geburtstag im April 2021 bevor. Wir ver- 14 / 29 binden einen Rückblick auf die spektakuläre Neuin- 10. Todestag von szenierung von Prokofjews Oper „Die Verlobung im Karen Chatschaturjan Kloster” an der Staatsoper Berlin 2019 mit Kurzdar- stellungen ausgewählter Werke. 15 / 29 Edison Denissow Der 25. Todestag des Russen Edison Denissow, aus- 25. Todestag am 24. November 2021 gewählte Gedenktage von Komponisten aus Georgien 18 / 30 und zwei 100. Geburtstage von bedeutenden Text- Jubiläen litauischer dichtern wie Stanisław Lem und Francisco Tanzer Interpreten und Komponisten sind weitere Themen dieser Ausgabe. David Geringas & Bronius Kutavičius Wir wünschen Ihnen eine interessante Lektüre und viele Entdeckungen, 20 / 32 News Winfried Jacobs 19 Geschäftsführer Geburts- und Kennen Sie auch die anderen Gedenktage 2021 Hefte des SIKORSKI Magazins? 21 Vorschau 2022 IMPRESSUM FOTONACHWEISE Titel Sofia Gubaidulina © Priska Ketterer S. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

From Proletarian Internationalism to Populist

from proletarian internationalism to populist russocentrism: thinking about ideology in the 1930s as more than just a ‘Great Retreat’ David Brandenberger (Harvard/Yale) • [email protected] The most characteristic aspect of the newly-forming ideology... is the downgrading of socialist elements within it. This doesn’t mean that socialist phraseology has disappeared or is disappearing. Not at all. The majority of all slogans still contain this socialist element, but it no longer carries its previous ideological weight, the socialist element having ceased to play a dynamic role in the new slogans.... Props from the historic past – the people, ethnicity, the motherland, the nation and patriotism – play a large role in the new ideology. –Vera Aleksandrova, 19371 The shift away from revolutionary proletarian internationalism toward russocentrism in interwar Soviet ideology has long been a source of scholarly controversy. Starting with Nicholas Timasheff in 1946, some have linked this phenomenon to nationalist sympathies within the party hierarchy,2 while others have attributed it to eroding prospects for world This article builds upon pieces published in Left History and presented at the Midwest Russian History Workshop during the past year. My eagerness to further test, refine and nuance this reading of Soviet ideological trends during the 1930s stems from the fact that two book projects underway at the present time pivot on the thesis advanced in the pages that follow. I’m very grateful to the participants of the “Imagining Russia” conference for their indulgence. 1 The last line in Russian reads: “Bol’shuiu rol’ v novoi ideologii igraiut rekvizity istoricheskogo proshlogo: narod, narodnost’, rodina, natsiia, patriotizm.” V. -

From Folk Source to Professional Creation

GESJ: Musicology and Cultural Science 2019|No.1(19) ISSN 1512-2018 UDC - 78 FROM FOLK SOURCE TO PROFESSIONAL CREATION: ON ONE TUSHETIAN TUNE Zumbadze Natalia, Matiashvili Ketevan Vano Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire, 8-10 Griboedov st. Summary: The article discusses the distribution area and development of one Tushetian tune mostly known as Mtsqemsuri. Today unison performance of this polyphonic melody, by nature, is explained as a decline of the process of Georgian traditional polyphonic thinking. The article also touches upon the examples of academic music, folk-jazz, author’s folklore, popular genre, which are successful or unsuccessful attempts of arranging the folk source. Keywords: Georgian (Tushetian) music, mtsqemsuri, Arjevnishvili, Tsintsadze, Erkomaishvili, Ebralidze. When researching Georgian-North Caucasian parallels in addition to archival materials preserved at the Georgian Folk Music Laboratory we got familiarized with the audio recordings copied by ethnomusicologist Manana Shilakadze from the archives of Dagestan State Television and Radio Committee in 1981. These included a panduri piece entitled “Georgian motive” performed by renowned Avarian folk professional Ramazan Magomedov (audio ex. N1). This is the tune that Sulkhan Tsintsadze used in one of his quartet miniatures “Mtsqemsuri” (Shepherd’s song), which is the final fifth part (Simghera; Gaprindi, shavo mertskhalo; Satsekvao; Khumroba, Mtsqemsuri) of the quartet suite composed in 1951 (audio ex. N2). Sulkhan Tsintsadze’s miniatures are more or less discussed in musicological literature. All authors unanimously recognize their folk basis, but the specific source of Mtsqemsuri is not indicated anywhere [1:47]; [2:107, 111]; [3:74, 75, 90, 94]. The notated version of the tune published by the Republican House of Folk Art in 1964 is entitled Tushuri satrpialo (Tushetian love song), with well-known singer, choir master and virtuoso panduri player Mariam Arjevnishvili (1918-1958) indicated as the author (her husband Geronti Tughushi is the author of the verbal text) (notated ex. -

Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921) by Dr

UDC 9 (479.22) 34 Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921) by Dr. Levan Z. Urushadze (Tbilisi, Georgia) ISBN 99940-0-539-1 The Democratic Republic of Georgia (DRG. “Sakartvelos Demokratiuli Respublika” in Georgian) was the first modern establishment of a Republic of Georgia in 1918 - 1921. The DRG was established after the collapse of the Russian Tsarist Empire that began with the Russian Revolution of 1917. Its established borders were with Russia in the north, and the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus, Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan in the south. It had a total land area of roughly 107,600 km2 (by comparison, the total area of today's Georgia is 69,700 km2), and a population of 2.5 million. As today, its capital was Tbilisi and its state language - Georgian. THE NATIONAL FLAG AND COAT OF ARMS OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF GEORGIA A Trans-Caucasian house of representatives convened on February 10, 1918, establishing the Trans-Caucasian Democratic Federative Republic, which existed from February, 1918 until May, 1918. The Trans-Caucasian Democratic Federative Republic was managed by the Trans-Caucasian Commissariat chaired by representatives of Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia. On May 26, 1918 this Federation was abolished and Georgia declared its independence. Politics In February 1917, in Tbilisi the first meeting was organised concerning the future of Georgia. The main organizer of this event was an outstanding Georgian scientist and public benefactor, Professor Mikheil (Mikhako) Tsereteli (one of the leaders of the Committee -

Print This Article

Number 2301 Alexander Kolchinsky Stalin on Stamps and other Philatelic Materials: Design, Propaganda, Politics Number 2301 ISSN: 2163-839X (online) Alexander Kolchinsky Stalin on Stamps and other Philatelic Materials: Design, Propaganda, Politics This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This site is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program, and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Alexander Kolchinsky received his Ph. D. in molecular biology in Moscow, Russia. During his career in experimental science in the former USSR and later in the USA, he published more than 40 research papers, reviews, and book chapters. Aft er his retirement, he became an avid collector and scholar of philately and postal history. In his articles published both in Russia and in the USA, he uses philatelic material to document the major historical events of the past century. Dr. Kolchinsky lives in Champaign, Illinois, and is currently the Secretary of the Rossica Society of Russian Philately. No. 2301, August 2013 2013 by Th e Center for Russian and East European Studies, a program of the Uni- versity Center for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh ISSN 0889-275X (print) ISSN 2163-839X (online) Image from cover: Stamps of Albania, Bulgaria, People’s Republic of China, German Democratic Republic, and the USSR reproduced and discussed in the paper. The Carl Beck Papers Publisher: University Library System, University of Pittsburgh Editors: William Chase, Bob Donnorummo, Robert Hayden, Andrew Konitzer Managing Editor: Eileen O’Malley Editorial Assistant: Tricia J. -

Adjara Group Hospitality

CATALOGUE OF BUSINESS COOPERATION PROFILES OF COMPANIES BY SECTORS OPERATING IN GEORGIA October, 2019 www.eugbc.net Contents Energy, Oil & Gas.............................................................................................................................................. 4 Banks................................................................................................................................................................ 15 Free Industrial Zones & Investment Opportunities ......................................................................................... 19 Legal Services/Consulting/Auditing ................................................................................................................ 23 Tourism & Hospitality ..................................................................................................................................... 39 Food & Beverages/Animal Feed ...................................................................................................................... 49 Construction & Industrial Products ................................................................................................................. 58 Transport & Logistics ...................................................................................................................................... 69 Communications & IT ..................................................................................................................................... 75 Medicine & Insurance ..................................................................................................................................... -

Ip Georgia Journal Hiha1wc.Pdf

Tavmjdomaris sveti Chairman’s COLUMN Zvirfaso mkiTxvelo, dameTanxmebiT, metad sapasuxismgebloa saTaveSi edge im uwyebas, romelic icavs inteleqtualur sakuTrebas _ qveynisTvis yvelaze Rirebul aqtivs warsulSi, awmyosa da momavalSi. kidev ufro sapasuxismgebloa, roca es qveyana saqarTveloa _ saxelmwifo, romlisTvisac inteleq tualuri sa kuTrebis yvela obieqtis dacva Tanabar mniSvnelobas atarebs; qveyana, romelsac istoriulad aqvs udidesi inteleqtualuri aqtivi da mudmivi swrafva siaxlisa da inovaciisaken. saerTaSoriso eqspertebi adastureben, rom dRevandel msoflioSi msxvili kompaniebis qonebis 6070%s ara materialuri, aramed inteleqtualuri Dear Reader, aqtivebi (patentebi, sasaqonlo niSnebi, nouhau da As you may agree, it is a great responsibility to lead the sxv.) Seadgens. arc is aris siaxle, rom Tanamedrove agency that protects intellectual property – the most valuable msoflio ekonomikaSi, mkacri konkurenciis pirobebSi, asset for any country from the point of view of past, present gansakuTrebul warmatebas aRweven inovaciur teq and future. The fact that this country is Georgia makes my job nologiebze orientirebuli kompaniebi (Microsoft, Apple even more responsible; the country where protection of all ob- da a.S.). inteleqtualuri sakuTrebis sfero yvela jects of intellectual property is equally important; the country Cvenganis cxovrebis nawilia. zogi qmnis inteleq with the greatest historical intellectual asset and a constant tualur sakuTrebis obieqts _ `produqts~, zogi ki strive for novelty and innovation. moixmars mas. Cveni movaleobaa am procesis kanonierad It has been confirmed by intellectual experts that intellectu- da saerTaSorisod miRebuli wesebiT warmarTvis uz al assets (patents, trademarks, know-how and etc.) as opposed runvelyofa. to material ones make up 60-70% of property of major com- damoukidebel saqarTveloSi inteleqtualuri sa panies in the contemporary world. It is a common knowledge kuTrebis dacvas ukve 20wliani istoria aqvs.