Goldman Nationallly Informed Full Draft 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

Edinburgh International Festival 1962

WRITING ABOUT SHOSTAKOVICH Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Edinburgh Festival 1962 working cover design ay after day, the small, drab figure in the dark suit hunched forward in the front row of the gallery listening tensely. Sometimes he tapped his fingers nervously against his cheek; occasionally he nodded Dhis head rhythmically in time with the music. In the whole of his productive career, remarked Soviet Composer Dmitry Shostakovich, he had “never heard so many of my works performed in so short a period.” Time Music: The Two Dmitrys; September 14, 1962 In 1962 Shostakovich was invited to attend the Edinburgh Festival, Scotland’s annual arts festival and Europe’s largest and most prestigious. An important precursor to this invitation had been the outstanding British premiere in 1960 of the First Cello Concerto – which to an extent had helped focus the British public’s attention on Shostakovich’s evolving repertoire. Week one of the Festival saw performances of the First, Third and Fifth String Quartets; the Cello Concerto and the song-cycle Satires with Galina Vishnevskaya and Rostropovich. 31 DSCH JOURNAL No. 37 – July 2012 Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya in Edinburgh Week two heralded performances of the Preludes & Fugues for Piano, arias from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Sixth, Eighth and Ninth Symphonies, the Third, Fourth, Seventh and Eighth String Quartets and Shostakovich’s orches- tration of Musorgsky’s Khovanschina. Finally in week three the Fourth, Tenth and Twelfth Symphonies were per- formed along with the Violin Concerto (No. 1), the Suite from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Three Fantastic Dances, the Cello Sonata and From Jewish Folk Poetry. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

From Proletarian Internationalism to Populist

from proletarian internationalism to populist russocentrism: thinking about ideology in the 1930s as more than just a ‘Great Retreat’ David Brandenberger (Harvard/Yale) • [email protected] The most characteristic aspect of the newly-forming ideology... is the downgrading of socialist elements within it. This doesn’t mean that socialist phraseology has disappeared or is disappearing. Not at all. The majority of all slogans still contain this socialist element, but it no longer carries its previous ideological weight, the socialist element having ceased to play a dynamic role in the new slogans.... Props from the historic past – the people, ethnicity, the motherland, the nation and patriotism – play a large role in the new ideology. –Vera Aleksandrova, 19371 The shift away from revolutionary proletarian internationalism toward russocentrism in interwar Soviet ideology has long been a source of scholarly controversy. Starting with Nicholas Timasheff in 1946, some have linked this phenomenon to nationalist sympathies within the party hierarchy,2 while others have attributed it to eroding prospects for world This article builds upon pieces published in Left History and presented at the Midwest Russian History Workshop during the past year. My eagerness to further test, refine and nuance this reading of Soviet ideological trends during the 1930s stems from the fact that two book projects underway at the present time pivot on the thesis advanced in the pages that follow. I’m very grateful to the participants of the “Imagining Russia” conference for their indulgence. 1 The last line in Russian reads: “Bol’shuiu rol’ v novoi ideologii igraiut rekvizity istoricheskogo proshlogo: narod, narodnost’, rodina, natsiia, patriotizm.” V. -

IBA Academic League - March - Round 4

IBA Academic League - March - Round 4 1. In 1697, he went incognito as a part of a grand embassy to secureallies in western Europe for a revolt against the Turks. He returnedto Moscow to suppress a revolt, and then began his reforms. He centralized the administration, abolished the old council of the boyars, established a senate, and encouraged trade, industry, and education. Name this Russian Tsar who ruled until his death in 1725,after which his second wife, Catherine I, ascended to the throne. Answer: Peter I or The Great 2. Born in Brookline, Massachusetts, she was privately educated andwidely traveled, but did not turn to poetry until the age of twenty-eight. Many of her poems describe the pastoral settings of NewEngland, and her posthumous collection of poems, What's O'Clock, wonthe Pulitzer Prize in 1925. Name this influential Imagist of the early 20th century whose major collections include Can Grande's Castle, Legends,and Sword Blades and Poppy Seeds. Answer: Amy Lowell 3. This country's legends claim that the hero Maui yanked its Pacific islands from the sea with a fishhook acquired from the Samoans. Cookvisited the islands in 1773, 1774, and 1777, calling them "The FriendlyIslands". The island groups of Vava'u, Nomaku, and Ha'apai comprise parts of this country, and its capital means "abode of love". What is country with its capital at Nuku'alofa? Answer: Tonga 4. In Babylonian mythology, this goddess ventured into the kingdom ofdeath when one of her lovers, Tammuz, died. She was imprisoned thereand assaulted with sixty illnesses by the queen of the dead, Ereshkigal.In her absence the Earth withered and became barren, but when Ea, the god of wisdom, allowed her to leave along with her lover, the Earth changed from winter into spring. -

Print This Article

Number 2301 Alexander Kolchinsky Stalin on Stamps and other Philatelic Materials: Design, Propaganda, Politics Number 2301 ISSN: 2163-839X (online) Alexander Kolchinsky Stalin on Stamps and other Philatelic Materials: Design, Propaganda, Politics This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This site is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program, and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Alexander Kolchinsky received his Ph. D. in molecular biology in Moscow, Russia. During his career in experimental science in the former USSR and later in the USA, he published more than 40 research papers, reviews, and book chapters. Aft er his retirement, he became an avid collector and scholar of philately and postal history. In his articles published both in Russia and in the USA, he uses philatelic material to document the major historical events of the past century. Dr. Kolchinsky lives in Champaign, Illinois, and is currently the Secretary of the Rossica Society of Russian Philately. No. 2301, August 2013 2013 by Th e Center for Russian and East European Studies, a program of the Uni- versity Center for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh ISSN 0889-275X (print) ISSN 2163-839X (online) Image from cover: Stamps of Albania, Bulgaria, People’s Republic of China, German Democratic Republic, and the USSR reproduced and discussed in the paper. The Carl Beck Papers Publisher: University Library System, University of Pittsburgh Editors: William Chase, Bob Donnorummo, Robert Hayden, Andrew Konitzer Managing Editor: Eileen O’Malley Editorial Assistant: Tricia J. -

'Revolutionary' to 'Progressive': Musical Ationalism in Rimsky-Korsakov's

From ‘revolutionary’ to ‘progressive’: Musical ationalism in Rimsky-Korsakov’s Russian Easter Overture © 2006 Helen. K. H. Wong “Can Byelayev’s circle be looked upon as a continuation of Balakirev’s? Was there a certain modicum of similarity between one and the other and what constituted the difference, apart from the change in personnel in the course of time? The similarity indicating that Byelayev’s circle was a continuation of Balakirev’s circle (in addition to the connecting links, consisted of the advanced ideas, the progressivism, common to the both of them. But Balakirev’s circle corresponded to the period of storm and stress in the evolution of Russian music; Byelayev’s circle represented the period of calm and onward march. Balakirev’s circle was revolutionary; Byelayev’s, on the other hand was progressive.” (Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, p. 286) “Who had changed, who had advanced – Balakirev or we? We, I suppose. We had grown, had learned, had been educated, had seen, and had heard; Balakirev, on the other hand, had stood stock-still, if, indeed, he had not slid back a trifle.” (Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, p. 286) By the time Rimsky-Korsakov wrote his “Russian Easter” Overture for Byelayev in 1888, the kuchka group, a group of five St. Petersburg composers which was once considered as “revolutionary” in its aesthetic ideal, was scattered. Musorgsky was no longer among the living, Borodin’s creativity came to a halt with his Prince Igor left unfinished, Cesar Cui no longer counted as a composer. Balakirev, although still a collaborator of Rimsky-Korsakov for their joint duties in the Imperial Court Chapel, was not only socially diverged from his younger colleague for his enmity towards Byelayev, but also had undergone some kind of ideological transformation himself. -

Karnavi Ius Jurgis Karnavičius Jurgis Karnavičius (1884–1941)

JURGIS KARNAVI IUS JURGIS KARNAVIČIUS JURGIS KARNAVIČIUS (1884–1941) String Quartet No. 3, Op. 10 (1922) 33:13 I. Andante 8:00 2 II. Allegro 11:41 3 III. Lento tranquillo 13:32 String Quartet No. 4 (1925) 28:43 4 I. Moderato commodo 11:12 5 II. Andante 8:04 6 III. Allegro animato 9:27 World première recordings VILNIUS STRING QUARTET DALIA KUZNECOVAITĖ, 1st violin ARTŪRAS ŠILALĖ, 2nd violin KRISTINA ANUSEVIČIŪTĖ, viola DEIVIDAS DUMČIUS, cello 3 Epoch-unveiling music This album revives Jurgis Karnavičius’ (1884–1941) chamber music after many years of oblivion. It features the last two of his four string quartets, written in 1913–1925 while he was still living in St. Petersburg. Due to the turns and twists of the composer’s life these magnificent 20th-century chamber music opuses were performed extremely rarely after his death, thus the more pleasant discovery awaits all who will listen to these recordings. The Vilnius String Quartet has proceeded with a meaningful initiative to discover and resurrect those pages of Lithuanian quartet music that allow a broader view of Lithuanian music and testify to the internationality of our musical culture and connections with global music communities in momentous moments of the development of both Lithuanian and European music. In early stages of the 20th-century, not only Lithuanian national art, but also the concept of contemporary music and the ideas of international cooperation of musicians were formed on a global scale. Jurgis Karnavičius is a significant figure in Lithuanian music not only as a composer, having produced the first Lithuanian opera of the independence period – Gražina (based on a poem by Adam Mickiewicz) in 1933, but also as a personality, active in the orbit of the international community of contemporary musicians. -

East Asians in Soviet Intelligence and the Chinese-Lenin School of the Russian Far East

East Asians in Soviet Intelligence and the Chinese-Lenin School of the Russian Far East Jon K. Chang Abstract1 This study focuses on the Chinese-Lenin School (also the acronym CLS) and how the Soviet state used the CLS and other tertiary institutions in the Russian Far East to recruit East Asians into Soviet intelligence during the 1920s to the end of 1945. Typically, the Chinese and Korean intelligence agents of the USSR are presented with very few details with very little information on their lives, motivations and beliefs. This article will attempt to bridge some of this “blank spot” and will cover the biographies of several East Asians in the Soviet intelligence services, their raison d’être, their world view(s) and motivations. The basis for this new study is fieldwork, interviews and photographs collected and conducted in Central Asia with the surviving relatives of six East Asian former Soviet intelligence officers. The book, Chinese Diaspora in Vladivostok, Second Edition [Kitaiskaia diaspora vo Vladivostoke, 2-е izdanie] which was written in Russian by two local historians from the Russian Far East also plays a major role in this study’s depth, revelations and conclusions.2 Methodology: (Long-Term) Oral History and Fieldwork My emphasis on “oral history” in situ is based on the belief that the state archives typically chronicle and tell a history in which the state, its officials and its institutions are the primary actors and “causal agents” who create a powerful, actualized people from the common clay of workers, peasants and sometimes, draw from society’s more marginalized elements such as vagabonds and criminals. -

Edison Denisov Contemporary Music Studies

Edison Denisov Contemporary Music Studies A series of books edited by Peter Nelson and Nigel Osborne, University of Edinburgh, UK Volume 1 Charles Koechlin (1867–1950): His Life and Works Robert Orledge Volume 2 Pierre Boulez—A World of Harmony Lev Koblyakov Volume 3 Bruno Maderna Raymond Fearn Volume 4 What’s the Matter with Today’s Experimental Music? Organized Sound Too Rarely Heard Leigh Landy Additional volumes in preparation: Stefan Wolpe Austin Clarkson Italian Opera Music and Theatre Since 1945 Raymond Fearn The Other Webern Christopher Hailey Volume 5 Linguistics and Semiotics in Music Raymond Monelle Volume 6 Music Myth and Nature François-Bernard Mache Volume 7 The Tone Clock Peter Schat Volume 8 Edison Denisov Yuri Kholopov and Valeria Tsenova Volume 9 Hanns Eisler David Blake Cage and the Human Tightrope David Revill Soviet Film Music: A Historical Perspective Tatyana Yegorova This book is part of a series. The publisher will accept continuation orders which may be cancelled at any time and which provide for automatic billing and shipping of each title in the series upon publication. Please write for details. Edison Denisov by Yuri Kholopov and Valeria Tsenova Moscow Conservatoire Translated from the Russian by Romela Kohanovskaya harwood academic publishers Australia • Austria • Belgium • China • France • Germany • India Japan • Malaysia • Netherlands • Russia • Singapore • Switzerland Thailand • United Kingdom • United States Copyright © 1995 by Harwood Academic Publishers GmbH. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

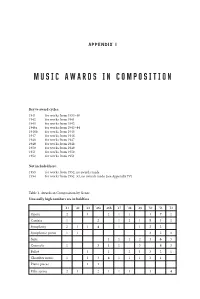

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4.