The Caucasus Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

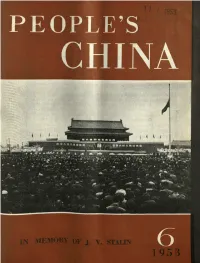

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

A Short History of Georgian Architecture

A SHORT HISTORY OF GEORGIAN ARCHITECTURE Georgia is situated on the isthmus between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. In the north it is bounded by the Main Caucasian Range, forming the frontier with Russia, Azerbaijan to the east and in the south by Armenia and Turkey. Geographically Georgia is the meeting place of the European and Asian continents and is located at the crossroads of western and eastern cultures. In classical sources eastern Georgia is called Iberia or Caucasian Iberia, while western Georgia was known to Greeks and Romans as Colchis. Georgia has an elongated form from east to west. Approximately in the centre in the Great Caucasian range extends downwards to the south Surami range, bisecting the country into western and eastern parts. Although this range is not high, it produces different climates on its western and eastern sides. In the western part the climate is milder and on the sea coast sub-tropical with frequent rains, while the eastern part is typically dry. Figure 1 Map of Georgia Georgian vernacular architecture The different climates in western and eastern Georgia, together with distinct local building materials and various cultural differences creates a diverse range of vernacular architectural styles. In western Georgia, because the climate is mild and the region has abundance of timber, vernacular architecture is characterised by timber buildings. Surrounding the timber houses are lawns and decorative trees, which rarely found in the rest of the country. The population and hamlets scattered in the landscape. In eastern Georgia, vernacular architecture is typified by Darbazi, a type of masonry building partially cut into ground and roofed by timber or stone (rarely) constructions known as Darbazi, from which the type derives its name. -

The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961) Nikolaos Biziouras Published Online: 14 Apr 2013

This article was downloaded by: [US Naval Academy] On: 25 June 2013, At: 06:09 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Journal of the Middle East and Africa Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujme20 The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961) Nikolaos Biziouras Published online: 14 Apr 2013. To cite this article: Nikolaos Biziouras (2013): The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961), The Journal of the Middle East and Africa, 4:1, 21-46 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21520844.2013.771419 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection -

Musefication of the Architectural Legacy of Medieval Alania

MATEC Web of Conferences 106, 01008 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/ matecconf/201710601008 SPbWOSCE-2016 Musefication of the architectural legacy of Medieval Alania Julia Treyman1,* 1Don State Technical University, pl. Gagarina, 1, Rostov-on-Don, 344010, Russia Abstract. The article is devoted to the particularities of the process of musefication of the historic and cultural legacy of Medieval Alania, an integral part of natural landscapes of the North Caucasus. It turned up that the natural and spacial carcass of the North Depression pot hole was the particular scenario for the development of territorial and spacial organization of settlements. The carcass is also the basis for the development of the museum exposition. Museum and touristic routes can be created following ancient trade routes, along which the alans created their settlements. The alans animated the nature and created a network of sacred objects. It can be represented in the form of a carcass structure consisting of sacral objects (such as sacred mountains, trees, groves, springs, lakes, separate stones, caves etc.). The sacred objects and the routes to them formed sacred topography of Alania. They can be used as the centerpieces of the museum and tourist routes. The alani settlements situated along the roads can be the main elements of expositions. Revealing and preserving spacial structure and historic connections between the objects of the main exposition should be the basis of our conception of musefication of the historic and cultural landscape of Medieval Alania. This decision will let us demonstrate the unique objects of region’s cultural legacy including the historic landscape in the best possible way. -

BÖLGESEL Sayı | Issue: 01 ARAŞTIRMALAR Mayıs | May 2017 DERGİSİ

Cilt | Volume: 01 BÖLGESEL Sayı | Issue: 01 ARAŞTIRMALAR Mayıs | May 2017 DERGİSİ Russian Hybrid Warfare and its Implications in the Black Sea Şafak OĞUZ Globalization and its Impact on the Post-Cold War Era Ethiopia’s Foreign Policy Muzeyin Hawas SEBSEBE اﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﺔ اﻟﺨﺎرﺟﻴﺔ اﻟﻌﺮاﻗﻴﺔ ﺑ اﻟﻨﻈﺮﻳﺔ واﻟﺘﻄﺒﻴﻖ دراﺳﺔ ﺣﺎﻟﺔ اﻟﻌﻼﻗﺎت اﻟﻌﺮاﻗﻴﺔ–اﻟﺴﻌﻮدﻳﺔ ﺣﺘﻰ ﻋﺎم 2014 وآﻓﺎﻗﻬﺎ اﳌﺴﺘﻘﺒﻠﻴﺔ Ali Bashar AGWAN Jeltoksan Ayaklanması ve Bu Ayaklanmanın Kazakistan’ın Bağımsızlığındaki Rolü Doğacan BAŞARAN Turkish President Turgut Özal’s Impact on Nursultan Nazarbayev’s Perception of Turkey Dinmuhammed AMETBEK روﺳﻴﺎ اﻻﺗﺤﺎدﻳﺔ اﻟﻘﻮة اﻟﺼﺎﻋﺪة: ﻣﻘﻮﻣﺎت اﻟﻘﻮة وﻧﻘﺎط اﻟﻀﻌﻒ Ahmed Yousif KIETAN ANKARA KRİZ VE SİYASET ARAŞTIRMALARI MERKEZİ ANKASAM ANKARA CENTER FOR CRISIS AND POLICY STUDIES AHKACAM Анкарский центр исследований кризисных ситуаций и политики ﻣﺮﻛــﺰ ا ﻧﻘــﺮ ة ﻟـﺪ ر ا ﺳـــــﺔ ا ﻻ ز ﻣــﺎ ت و ا ﻟﺴــﻴﺎ ﺳــــــﺎ ت ﻣﺮﮐــﺰ ﭘﮋوﻫﺸـــﻬﺎى ﺑﺤـــﺮان و ﺳﯿﺎﺳــﺖ آﻧﮑــــــــــﺎرا اﻧﮑﺎﺳـــــــــﺎم Cilt: 1 • Sayı: 1 • Mayıs 2017 Bölgesel Araştırmalar Dergisi Yılda İki Defa Yayımlanır SAHIBI Prof. Dr. Mehmet Seyfettin EROL EDITÖR Prof. Dr. Mehmet Seyfettin EROL EDITÖR YARDIMCISI Dr. Dinmuhammed AMETBEK SORUMLU YAZI IŞLERI MÜDÜRÜ Kadir Ertaç ÇELİK YAYINA HAZIRLAYANLAR Sami BURGAZ Firas ELİAS İbrahim NASSİR Muzeyyin SEBSEBE Cenk TAMER Sezen Sıla ZÜLBAHAR YAYIN KURULU Prof. Dr. Muthana AL-MAHDAWİ • Bağdat Üniversitesi Prof. Dr. İbrahim Ethem ATNUR • Atatürk Üniversitesi Prof. Dr. Hacı DURAN • Adıyaman Üniversitesi Prof. Dr. Hacı Mustafa ERAVCI • Yıldırım Beyazıt Prof. Dr. Temuçin Faik ERTAN • Ankara Üniversitesi Prof. Dr. Bilgehan Atsız GÖKDAĞ • Kırıkkale Üniversitesi Prof. Dr. Osman KARATAY • Ege Üniversitesi Prof. Dr. Güray KIRPIK • Gazi Üniversitesi Prof. Dr. Hasan KÖNİ • İstanbul Kültür Üniversitesi Prof. Dr. -

An Essay in Universal History

AN ESSAY IN UNIVERSAL HISTORY From an Orthodox Christian Point of View VOLUME VI: THE AGE OF MAMMON (1945 to 1992) PART 2: from 1971 to 1992 Vladimir Moss © Copyright Vladimir Moss, 2018: All Rights Reserved 1 The main mark of modern governments is that we do not know who governs, de facto any more than de jure. We see the politician and not his backer; still less the backer of the backer; or, what is most important of all, the banker of the backer. J.R.R. Tolkien. It is time, it is the twelfth hour, for certain of our ecclesiastical representatives to stop being exclusively slaves of nationalism and politics, no matter what and whose, and become high priests and priests of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church. Fr. Justin Popovich. The average person might well be no happier today than in 1800. We can choose our spouses, friends and neighbours, but they can choose to leave us. With the individual wielding unprecedented power to decide her own path in life, we find it ever harder to make commitments. We thus live in an increasingly lonely world of unravelling commitments and families. Yuval Noah Harari, (2014). The time will come when they will not endure sound doctrine, but according to their own desires, because they have itching ears, will heap up for themselves teachers, and they will turn their ears away from the truth, and be turned aside to fables. II Timothy 4.3-4. People have moved away from ‘religion’ as something anchored in organized worship and systematic beliefs within an institution, to a self-made ‘spirituality’ outside formal structures, which is based on experience, has no doctrine and makes no claim to philosophical coherence. -

Acceptance and Rejection of Foreign Influence in the Church Architecture of Eastern Georgia

The Churches of Mtskheta: Acceptance and Rejection of Foreign Influence in the Church Architecture of Eastern Georgia Samantha Johnson Senior Art History Thesis December 14, 2017 The small town of Mtskheta, located near Tbilisi, the capital of the Republic of Georgia, is the seat of the Georgian Orthodox Church and is the heart of Christianity in the country. This town, one of the oldest in the nation, was once the capital and has been a key player throughout Georgia’s tumultuous history, witnessing not only the nation’s conversion to Christianity, but also the devastation of foreign invasions. It also contains three churches that are national symbols and represent the two major waves of church building in the seventh and eleventh centuries. Georgia is, above all, a Christian nation and religion is central to its national identity. This paper examines the interaction between incoming foreign cultures and deeply-rooted local traditions that have shaped art and architecture in Transcaucasia.1 Nestled among the Caucasus Mountains, between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, present-day Georgia contains fewer than four million people and has its own unique alphabet and language as well as a long, complex history. In fact, historians cannot agree on how Georgia got its English exonym, because in the native tongue, kartulad, the country is called Sakartvelo, or “land of the karvelians.”2 They know that the name “Sakartvelo” first appeared in texts around 800 AD as another name for the eastern kingdom of Kartli in Transcaucasia. It then evolved to signify the unified eastern and western kingdoms in 1008.3 Most scholars agree that the name “Georgia” did not stem from the nation’s patron saint, George, as is commonly thought, but actually comes 1 This research addresses the multitude of influences that have contributed to the development of Georgia’s ecclesiastical architecture. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

From Proletarian Internationalism to Populist

from proletarian internationalism to populist russocentrism: thinking about ideology in the 1930s as more than just a ‘Great Retreat’ David Brandenberger (Harvard/Yale) • [email protected] The most characteristic aspect of the newly-forming ideology... is the downgrading of socialist elements within it. This doesn’t mean that socialist phraseology has disappeared or is disappearing. Not at all. The majority of all slogans still contain this socialist element, but it no longer carries its previous ideological weight, the socialist element having ceased to play a dynamic role in the new slogans.... Props from the historic past – the people, ethnicity, the motherland, the nation and patriotism – play a large role in the new ideology. –Vera Aleksandrova, 19371 The shift away from revolutionary proletarian internationalism toward russocentrism in interwar Soviet ideology has long been a source of scholarly controversy. Starting with Nicholas Timasheff in 1946, some have linked this phenomenon to nationalist sympathies within the party hierarchy,2 while others have attributed it to eroding prospects for world This article builds upon pieces published in Left History and presented at the Midwest Russian History Workshop during the past year. My eagerness to further test, refine and nuance this reading of Soviet ideological trends during the 1930s stems from the fact that two book projects underway at the present time pivot on the thesis advanced in the pages that follow. I’m very grateful to the participants of the “Imagining Russia” conference for their indulgence. 1 The last line in Russian reads: “Bol’shuiu rol’ v novoi ideologii igraiut rekvizity istoricheskogo proshlogo: narod, narodnost’, rodina, natsiia, patriotizm.” V. -

Delegation of Israel Supports Tourism in Georgia

Issue no: 1169 • JULY 19 - 22, 2019 • PUBLISHED TWICE WEEKLY PRICE: GEL 2.50 In this week’s issue... FOCUS Georgian Gov’t Offers Help to Tourism Sector after ON RUSTAVI 2 Russian Travel Ban OWNERSHIP NEWS PAGE 2 The ECHR releases its verdict PAGE 2 Sabkultura: Saba’s Subsidiary Brand for Contemporary Generations NEWS PAGE 3 On Some Issues of the History of Georgia POLITICS PAGE 4 What Are Moscow's Preconditions for Abolishing a Ban on Flights with Georgia? POLITICS PAGE 6 Meet Italian Chef Enzo Neri – Restaurateur, Philanthropist, Designer Delegation of Israel Supports Tourism in Georgia TRANSLATED BY KETEVAN KVARATSKHELIYA BUSINESS PAGE 7 ithin the scope of an offi cial invitation from Israeli House, Capacity Building Trainings the members of the Knesset of Israel and Likud Party of on the Topic of WaSH the Prime Minister Netan- Wyahu, along with the representatives of the Israeli SOCIETY PAGE 12 business sector and media, are paying a visit to Georgia. The delegation, comprising 25 delegates, is headed by Davit Bitan, the Leader of the rul- Nenskra Hydro Launches ing coalition of the Knesset. The aim of the visit is to hold business meet- Info Campaign to Promote ings and explore the tourist potential of Georgia on site. There has been an impressive increase Domestic Tourism in Svaneti in the Israeli tourist infl ow in Georgia in recent years. According to offi cial data, in comparison SOCIETY PAGE 13 with the fi rst half of 2018, in 2019 the number of tourists increased by 28.4%. Itsik Moshe, Presi- dent of the Israel-Georgia Chamber of Business Georgia to Host World- and Chair of the Israeli House, states that the number of travelers from Israel might reach Famous Verdi Festival 200,000 this year. -

International and Civil War Data, 1816-1992 (Wages of War)

UK Data Archive Study Number 3441 Correlates of War Project: International and Civil War Data, 1816-1992 (Wages of War) 1 CORRELATES OF WAR PROJECT: INTERNATIONAL AND CIVIL WAR DATA, 1816-1992 (ICPSR 9905) Principal Investigators J. David Singer University of Michigan Melvin Small Wayne State University First ICPSR Release April 1994 Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research P.O. Box 1248 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 1 1 BIBLIOGRAPHIC CITATION Publications based on ICPSR data collections should acknowledge those sources by means of bibliographic citations. To ensure that such source attributions are captured for social science bibliographic utilities, citations must appear in footnotes or in the reference section of publications. The bibliographic citation for this data collection is: Singer, J. David, and Melvin Small. CORRELATES OF WAR PROJECT: INTERNATIONAL AND CIVIL WAR DATA, 1816-1992 [Computer file]. Ann Arbor, MI: J. David Singer and Melvin Small [producers], 1993. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 1994. REQUEST FOR INFORMATION ON USE OF ICPSR RESOURCES To provide funding agencies with essential information about use of archival resources and to facilitate the exchange of information about ICPSR participants' research activities, users of ICPSR data are requested to send to ICPSR bibliographic citations for each completed manuscript or thesis abstract. Please indicate in a cover letter which data were used. DATA DISCLAIMER The original collector of the data, ICPSR, and the relevant funding agency bear no responsibility for uses of this collection or for interpretations or inferences based upon such uses. 1 1 DATA COLLECTION DESCRIPTION J. -

Report on the Implementation of the State Strategy for Civic Equality And

GOVERNMENT OF GEORGIA STATE INTER-AGENCY COMMISSION OFFICE OF THE STATE MINISTER OF GEORGIA FOR RECONCILIATION AND CIVIC EQUALITY REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF STATE STRATEGY FOR CIVIC EQUALITY AND INTEGRATION AND 2016 ACTION PLAN FEBRUARY 2017 1 Office of the State Minister of Georgia for Reconciliation and Civic Equality Address: 3/5 G. Leonidze Street, Tbilisi 0134 Telephone: (+995 32) 2923299; (+995 32) 2922632 Website: www.smr.gov.ge E-mail: [email protected] 2 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ I. EQUAL AND FULL PARTICIPATION IN CIVIC AND POLITICAL LIFE .......................................................................... 5 SUPPORTING SMALL AND VULNERABLE ETHNIC MINORITY GROUPS ........................................................... 5 GENDER MAINSTREAMING ...................................................................................................................... 7 IMPROVING ACCESS TO STATE ADMINISTRATIONS, LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES AND MECHANISMS FOR REPRESENTATIVES OF EHTNIC MINORITIES .............................................................................................. 9 PROVIDING EQUAL ELECTORAL CONDITIONS FOR ETHNIC MINORITY VOTERS .......................................... 12 PROVIDING ACCESS TO MEDIA AND INFORMATION ................................................................................ 16 II. CREATING EQUAL SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CONDITIONS AND OPPORTUNITIES ..................................................