Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seismic Philately

Seismic Philately adapted from the 2008 CUREE Calendar introduction by David J. Leeds © 2007 - All Rights Reserved. Stamps shown on front cover (left to right): • Label created by Chicago businessmen to help raise relief for the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake • Stamp commemorating the 1944 San Juan, Argentina Earthquake • Stamp commemorating the 1954 Orleansville, Algeria Earthquake • Stamp commemorating the 1953 Zante, Greece Earthquake • Stamp from 75th Anniversary stamp set commemorating the 1931 Hawkes Bay, New Zealand Earthquake • Stamp depicting a lake formed by a landslide triggered by the 1923 Kanto, Japan Earthquake Consortium of Universities for Research in Earthquake Engineering 1301 South 46th Street, Richmond, CA 94804-4600 tel: 510-665-3529 fax: 510-665-3622 CUREE http://www.curee.org Seismic Philately by David J. Leeds Introduction Philately is simply the collection and the study of postage stamps. Some of the Secretary of the Treasury, and as a last resort, bisected stamps could stamp collectors (philatelists) collect only from their native country, others be used for half their face value. (see March) collect from the stamp-issuing countries around the world. Other philately collections are defined by topic, such as waterfalls, bridges, men with beards, FDC, first day cover, or Covers, are sometimes created to commerate the nudes, maps, flowers, presidents, Americans on foreign stamps, etc. Many first day a new stamp is issued. As part of the presentation, an envelope of the world’s stamps that are related to the topic of earthquakes have been with the new postage stamp is cancelled on the first day of issue. Additional compiled in this publication. -

885-5,000 Years of Postal History, Pt 1

Sale 885 Tuesday, November 9, 2004 5,000 Years of Postal History THE DR. ROBERT LEBOW COLLECTION Part One: FOREIGN COUNTRIES AUCTION GALLERIES, INC. www.siegelauctions.com Sale 885 Tuesday, November 9, 2004 Lot 2109 Arrangement of Sale Afternoon session (Lots 2001-2181) Tuesday, November 9, at 2:30 p.m. Earliest Written Communication....pages 5 5,000 Years of Postal History Courier Mail and Early Postal Systems .. 6-14 Royal Mail and Documents...................... 15-17 The Dr. Robert LeBow Collection Pre-Stamp Postal Markings by Country.. 18-24 Stamped Mail by Country........................ 25-50 Part One: Foreign Offered without reserves Pre-sale exhibiton Monday, November 8 — 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. or by appointment (please call 212-753-6421) On-line catalogue, e-mail bid form, resources and the Siegel Encyclopedia are available on our web site: On the cover www.siegelauctions.com Mauritius (lot 2137) Dr. Robert LeBow R. ROBERT LEBOW, KNOWN TO HIS MANY FRIENDS SIMPLY AS “BOB”, Ddevoted his life to providing affordable health care to people in America and developing countries. Bob passed away on November 29, 2003, as a result of injuries sustained in July 2002 in an accident while bicycling to work at a community health center in Idaho, where he had been the medical director for more than 25 years. Bob was paralyzed as a result of the accident, and though he was not able to actively participate in philately, he still kept up by reading Linn’s and all of the stamp auction catalogues that came his way. -

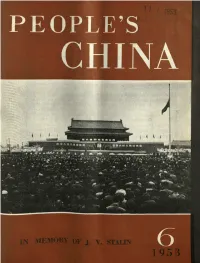

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

A History of Mail Classification and Its Underlying Policies and Purposes

A HISTORY OF MAIL CLASSIFICATION AND ITS UNDERLYING POLICIES AND PURPOSES Richard B. Kielbowicz AssociateProfessor School of Commuoications, Ds-40 University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195 (206) 543-2660 &pared For the Postal Rate Commission’s Mail ReclassificationProceeding, MC95-1. July 17. 1995 -- /- CONTENTS 1. Introduction . ._. ._.__. _. _, __. _. 1 2. Rate Classesin Colonial America and the Early Republic (1690-1840) ............................................... 5 The Colonial Mail ................................................................... 5 The First Postal Services .................................................... 5 Newspapers’ Mail Status .................................................... 7 Postal Policy Under the Articles of Confederation .............................. 8 Postal Policy and Practice in the Early Republic ................................ 9 Letters and Packets .......................................................... 10 Policy Toward Newspapers ................................................ 11 Recognizing Magazines .................................................... 12 Books in the Mail ........................................................... 17 3. Toward a Classitication Scheme(1840-1870) .................................. 19 Postal Reform Act of 1845 ........................................................ 19 Letters and the First Class, l&IO-l&?70 .............................. ............ 19 Periodicals and the Second Class ................................................ 21 Business -

Postal History Timeline

Postal History Timeline Early Romans and Persians had message and relay systems. 1775 Continental Congress creates a postal system and names Ben Franklin the Postmaster General. He had also been a postmaster for the crown. Among his achievements as Postmaster for the Crown were establishing new postal routes, establishing mile markers, and speeding up service. IMPORTANCE: In early times, correspondents depended on friends, merchants, and Native Americans to carry messages. In 1639 a tavern in Boston was designated as a mail repository. England had appointed Benjamin Franklin as Joint Postmaster General for the Crown in 1753. Franklin inspected all the post offices, and created new shorter routes. However, in 1774 Franklin was dismissed because his actions were sympathetic to the cause of the colonies. 1832 First time railroads were used by the Postal Service to carry the mail. In 1864, railroad cars were set up to carry mail and equipped so that mail could be sorted on the railroad car. Railroad mail service ended in 1977. IMPORTANCE: Apart from the employees, transportation was the single most important element in mail delivery. 1840 The first adhesive postage stamp is created in England as part of a postal reform movement spearheaded by Roland Hill. Quickly, other countries started using this system of ensuring letters were paid for. Before this system, people would send letters postage due, with codes in the address or as a blank letter. This way the message would be received, but the recipient would not pay for the letter. 1847 The first U.S. postage stamp is issued. 1858 Butterfield Overland Mail provides service between Missouri and California. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

From Proletarian Internationalism to Populist

from proletarian internationalism to populist russocentrism: thinking about ideology in the 1930s as more than just a ‘Great Retreat’ David Brandenberger (Harvard/Yale) • [email protected] The most characteristic aspect of the newly-forming ideology... is the downgrading of socialist elements within it. This doesn’t mean that socialist phraseology has disappeared or is disappearing. Not at all. The majority of all slogans still contain this socialist element, but it no longer carries its previous ideological weight, the socialist element having ceased to play a dynamic role in the new slogans.... Props from the historic past – the people, ethnicity, the motherland, the nation and patriotism – play a large role in the new ideology. –Vera Aleksandrova, 19371 The shift away from revolutionary proletarian internationalism toward russocentrism in interwar Soviet ideology has long been a source of scholarly controversy. Starting with Nicholas Timasheff in 1946, some have linked this phenomenon to nationalist sympathies within the party hierarchy,2 while others have attributed it to eroding prospects for world This article builds upon pieces published in Left History and presented at the Midwest Russian History Workshop during the past year. My eagerness to further test, refine and nuance this reading of Soviet ideological trends during the 1930s stems from the fact that two book projects underway at the present time pivot on the thesis advanced in the pages that follow. I’m very grateful to the participants of the “Imagining Russia” conference for their indulgence. 1 The last line in Russian reads: “Bol’shuiu rol’ v novoi ideologii igraiut rekvizity istoricheskogo proshlogo: narod, narodnost’, rodina, natsiia, patriotizm.” V. -

Obstetrics and Gynecology on Postage Stamps

Obstetrics and Gynecology on Postage Stamps: A Philatelic Study TURKAN GURSU1 and Alper Eraslan2 1SBU Zeynep Kamil Maternity and Pediatric Research and Training Hospital, Istanbul, TURKEY 2Dunya IVF, Kyrenia, Cyprus May 5, 2020 Abstract Objective:We tried to provide an overview of philatelic materials related to Gynecology and Obstetrics. Design:Sample philatelic materials including stamps, first day covers and stamped postcards, all related to obstetrics and gynecology, from the senior author’s personal archive were grouped according to their titles and evaluated in detail. Setting:We examine how stamp designers use visual imagery to convey information to those who see, collect, and use stamps. Method:Sample philatelic materials, related to obstetrics and gynecology, were grouped according to their titles and evaluated in detail. Main outcome measures:Stamps dedicated to the Obstetrics and Gynecology are usually printed in order to (a)pay tribute to the pioneers of Obstetrics and Gynecology, (b)commemorate important Obstetrics and Gynecology Facilities&Hospitals, (c)announce solid improvements and innovations in the field or (d)memorialize important meetings. Results:The initial use of postage stamps was solely to pay the fare of a postal service. Later on it was discovered that by using stamps it was possible to distribute ideas and news among people and also to inform them about developments, inventions, achievements and historical facts. Collecting Gynecology related philatelic materials is a very specialized branch of medical philately. In general, the subjects of the stamps dedicated to Obstetrics and Gynecology are, pioneers of Obstetrics and Gynecology, important Obstetrics and Gynecology Facilities&Hospitals, solid improvements and innovations in the field and important meetings. -

Bulletin 10-Final Cover

COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN Issue 10 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. March 1998 Leadership Transition in a Fractured Bloc Featuring: CPSU Plenums; Post-Stalin Succession Struggle and the Crisis in East Germany; Stalin and the Soviet- Yugoslav Split; Deng Xiaoping and Sino-Soviet Relations; The End of the Cold War: A Preview COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN 10 The Cold War International History Project EDITOR: DAVID WOLFF CO-EDITOR: CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN ADVISING EDITOR: JAMES G. HERSHBERG ASSISTANT EDITOR: CHRISTA SHEEHAN MATTHEW RESEARCH ASSISTANT: ANDREW GRAUER Special thanks to: Benjamin Aldrich-Moodie, Tom Blanton, Monika Borbely, David Bortnik, Malcolm Byrne, Nedialka Douptcheva, Johanna Felcser, Drew Gilbert, Christiaan Hetzner, Kevin Krogman, John Martinez, Daniel Rozas, Natasha Shur, Aleksandra Szczepanowska, Robert Wampler, Vladislav Zubok. The Cold War International History Project was established at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C., in 1991 with the help of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and receives major support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Smith Richardson Foundation. The Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to disseminate new information and perspectives on Cold War history emerging from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side”—the former Communist bloc—through publications, fellowships, and scholarly meetings and conferences. Within the Wilson Center, CWIHP is under the Division of International Studies, headed by Dr. Robert S. Litwak. The Director of the Cold War International History Project is Dr. David Wolff, and the incoming Acting Director is Christian F. -

What About Those Attractive Postage Stamps? Are They Copyrighted? Judith Nierman

Copyright Lore what about those attractive Postage stamps? are they Copyrighted? JuDith nieRman The job of postmaster general, first held by Benjamin Franklin, became a presidential cabinet position in 1829. The U.S. Post office operated continuously until the Postal Reorganization Act (P.L. 91-375) took effect in 1971, and the old Post office Department became the U.S. Postal Service (USPS). The comprehensive reorganization cost the Post office its position on the cabinet. Because postage stamps printed under used an unauthorized image Images, was not that of the the U.S. Post office were works of the U.S. of his sculptures on a postage iconic statue in New york’s government, stamps dating from before stamp and on merchandise harbor but of a recent replica created by Davidson that 1971 were not subject to copyright and sold by the USPS. The contractor is standing in front of a Las Vegas hotel. he registered are today in the public domain. responsible for designing and his claim to “Las Vegas Lady Liberty” in January 2012, and however, USPS stamps are constructing the memorial did it is recorded as VAu001090876. The suit was filed in copyrighted. The Compendium of not acquire the sculptor’s rights November 2013 in the Court of Federal Claims. The USPS Copyright Practices II says that “works in the work and thus could not has sold more than 4 billion copies of the stamp, according of the U.S. Postal Service, as now transfer them to the government. to the Washington Post. 1 constituted, are not considered U.S. -

Blacks on Stamp

BLACKS ON STAMP This catalog is published by The Africana Studies De- partment , University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Curator for the Blacks on Stamp Exhibition. February 13-17, 2012 Akin Ogundiran ©2012 Charlotte Papers in Africana Studies, Volume 3 2nd Edition Exhibition Manager ISBN 978-0-984-3449-2-5 Shontea L. Smith All rights reserved Presented and Sponsored by Exhibition Consultants Beatrice Cox Esper Hayes Aspen Hochhalter The Africana Studies Department The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Online Exhibition Consultants & Denelle Eads The College of Arts + Architecture Debbie Myers and Heather McCullough The Ebony Society of Philatetic Events and Reflections (ESPER) Office Manager Catalog DeAnne Jenkins by Akin Ogundiran and Shontea L. Smith BLACKS ON STAMP AFRICANA POSTAGE STAMPS WORLDWIDE Exhibition Rowe Arts Side Gallery February 13-17, 2012 CURATOR’S REMARKS About three years ago, Chancellor Philip Dubois introduced me to Dr. Esper Hayes via email. About a fortnight later, Dr. Hayes was in my office. In a meeting that lasted an hour or so, she drew me into her philatetic world. A wonderful friendship began. Since then, we have corresponded scores of times. She has also connected me with her vast network of stamp collectors, especially members of the organization she established for promoting Black-themed stamps all over the world – the Ebony Society of Philatetic Events and Reflec- tions (ESPER). This exhibition is the product of networks of collaborative efforts nurtured over many months. Blacks on Stamp is about preservation of memory and historical reflection. The objectives of the exhibition are to: (1) showcase the relevance of stamps as a form of material culture for the study of the history of the global Black experience; (2) explore the aesthetics and artistry of stamp as a genre of representative art, especially for understanding the Africana achievements globally; and (3) use the personalities and historical issues repre- sented on stamps to highlight some of the defining moments in national and world histories. -

Pitney Bowes Model M Postage Meter 1920

PITNEY BOWES MODEL M POSTAGE METER 1920 An International Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark, September 1986 The American Society of Mechanical Engineers PITNEY BOWES MODEL M POSTAGE METER Designated the 20th International Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers September 17, 1986 The original Pitney Bowes Model M postage meter, circa, 1920. Since its creation in 1789, the Post Office has THE INEFFICIENT POSTAGE STAMP been driven to make the mail move faster, more frequently, and more safely. Private enterprise Less than fifty years after the first conventional provided much of the innovation and success in postage stamps appeared in 1840 in England, improving the efficiency of postal service. Part of designs to eliminate them were well underway. In that history is the Pitney Bowes Model M postage 1884, Carle Bushe had conceived and patented a meter, which on November 16, 1920, became the machine similar to the postage meter but the first commercially used meter in the world. device was never used. In 1898, Elmer Wolf and William Scott experimented with a meter Though today’s meters are more sophisticated, machine for large-scale mailers which offered the the basic principles of the Model M are still in- Post Office security from theft, but no record ex- tact. The postage meter imprints an amount of ists to indicate that a model was built. In 1903, postage, functioning as a postage stamp, a the first government-authorized use of a cancellation mark, and a dated postmark all in mechanical device in place of adhesive stamps one. The well-known eagle meter stamp is proof took place in Norway, but this was abandoned of payment and eliminates the need for adhesive after a two-year trial.