From Proletarian Internationalism to Populist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War Communism and Bolshevik Ideals" Is Devoted to a Case I N Point: the Dispute Over the Motivation of War Communism (The Name Given T O

TITLE : WAR COMMUNISM AND BOLSHEVIK IDEAL S AUTHOR : LARS T . LIH THE NATIONAL COUNCI L FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEA N RESEARC H TITLE VIII PROGRA M 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 PROJECT INFORMATION : ' CONTRACTOR : Wellesley Colleg e PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Lars T. Li h COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 807-1 9 DATE : January 25, 199 4 COPYRIGHT INFORMATIO N Individual researchers retain the copyright on work products derived from research funded b y Council Contract. The Council and the U.S. Government have the right to duplicate written reports and other materials submitted under Council Contract and to distribute such copies within th e Council and U.S. Government for their own use, and to draw upon such reports and materials for their own studies; but the Council and U.S. Government do not have the right to distribute, o r make such reports and materials available, outside the Council or U.S. Government without th e written consent of the authors, except as may be required under the provisions of the Freedom o f information Act 5 U.S. C. 552, or other applicable law. The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research, made available by the U. S. Department of State under Title VIII (th e Soviet-Eastern European Research and Training Act of 1983) . The analysis and interpretations contained in th e report are those of the author. NCSEER NOTE This interpretive analysis of War Communism (1918-1921) may be of interest to those wh o anticipate further decline in the Russian economy and contemplate the possible purposes an d policies of a more authoritarian regime . -

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

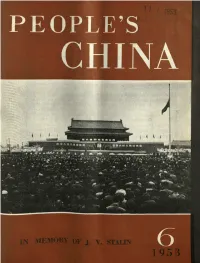

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

Colloquium Paper January 12, 1984 STALINISM VERSUS

Colloquium Paper January 12, 1984 STALINISM VERSUS BOLSHEVISM? A Reconsideration by Robert C. Tucker Princeton University with comment by Peter Reddaway London School of Economics and Political Science Fellows Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Draft paper not for publication or quotation without written permission from the authors. STALINISM VERSUS BOLSHEVISM? A Reconsideration Although not of ten openly debated~ the issue I propose to address is probably the deepest and most divisive in Soviet studies. There is good ground for Stephen Cohen's characterization of it as a "quintessential his torical and interpretive question"! because it transcends most of the others and has to do with the whole of Russia's historical development since the Bolshevik Revolution. He formulates it as the question of the relationship "between Bolshevism and Stalinism.'' Since the very existence of something properly called Stalinism is at issue here, I prefer a somewhat different mode of formulation. There are two (and curiously, only two) basically opposed positions on the course of development that Soviet Russia took starting around 1929 when Stalin, having ousted his opponents on the Left and the Right, achieved primacy, although not yet autocratic primacy, within the Soviet regime. The first position, Which may be seen as the orthodox one, sees that course of development as the fulfillment, under new conditions, of Lenin's Bolshevism. All the main actions taken by the Soviet regime under Stalin's leadership were, in other words, the fulfillment of what had been prefigured in Leninism (as Lenin's Bolshevism came to be called after Lenin died). -

The Russian Revolutions: the Impact and Limitations of Western Influence

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications 2003 The Russian Revolutions: The Impact and Limitations of Western Influence Karl D. Qualls Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Qualls, Karl D., "The Russian Revolutions: The Impact and Limitations of Western Influence" (2003). Dickinson College Faculty Publications. Paper 8. https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications/8 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Karl D. Qualls The Russian Revolutions: The Impact and Limitations of Western Influence After the collapse of the Soviet Union, historians have again turned their attention to the birth of the first Communist state in hopes of understanding the place of the Soviet period in the longer sweep of Russian history. Was the USSR an aberration from or a consequence of Russian culture? Did the Soviet Union represent a retreat from westernizing trends in Russian history, or was the Bolshevik revolution a product of westernization? These are vexing questions that generate a great deal of debate. Some have argued that in the late nineteenth century Russia was developing a middle class, representative institutions, and an industrial economy that, while although not as advanced as those in Western Europe, were indications of potential movement in the direction of more open government, rule of law, free market capitalism. Only the Bolsheviks, influenced by an ideology imported, paradoxically, from the West, interrupted this path of Russian political and economic westernization. -

A Crisis of Commitment: Socialist Internationalism in British Columbia During the Great War

A Crisis of Commitment: Socialist Internationalism in British Columbia during the Great War by Dale Michael McCartney B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2004 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of History © Dale Michael McCartney 2010 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2010 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Dale Michael McCartney Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: A Crisis of Commitment: Socialist Internationalism in British Columbia during the Great War Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Emily O‘Brien Assistant Professor of History _____________________________________________ Dr. Mark Leier Senior Supervisor Professor of History _____________________________________________ Dr. Karen Ferguson Supervisor Associate Professor of History _____________________________________________ Dr. Robert A.J. McDonald External Examiner Professor of History University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: ________4 March 2010___________________________ ii Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

The Communist Party of Great Britain Since 1920 Also by David Renton

The Communist Party of Great Britain since 1920 Also by David Renton RED SHIRTS AND BLACK: Fascism and Anti-Fascism in Oxford in the ‘Thirties FASCISM: Theory and Practice FASCISM, ANTI-FASCISM AND BRITAIN IN THE 1940s THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: A Century of Wars and Revolutions? (with Keith Flett) SOCIALISM IN LIVERPOOL: Episodes in a History of Working-Class Struggle THIS ROUGH GAME: Fascism and Anti-Fascism in European History MARX ON GLOBALISATION CLASSICAL MARXISM: Socialist Theory and the Second International The Communist Party of Great Britain since 1920 James Eaden and David Renton © James Eaden and David Renton 2002 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2002 978-0-333-94968-9 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2002 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. -

The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Legacies

1 The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Legacies Vladimir Tismaneanu The revolutions of 1989 were, no matter how one judges their nature, a true world-historical event, in the Hegelian sense: they established a historical cleavage (only to some extent conventional) between the world before and after 89. During that year, what appeared to be an immutable, ostensibly indestructible system collapsed with breath-taking alacrity. And this happened not because of external blows (although external pressure did matter), as in the case of Nazi Germany, but as a consequence of the development of insuperable inner tensions. The Leninist systems were terminally sick, and the disease affected first and foremost their capacity for self-regeneration. After decades of toying with the ideas of intrasystemic reforms (“institutional amphibiousness”, as it were, to use X. L. Ding’s concept, as developed by Archie Brown in his writings on Gorbachev and Gorbachevism), it had become clear that communism did not have the resources for readjustment and that the solution lay not within but outside, and even against, the existing order.1 The importance of these revolutions cannot therefore be overestimated: they represent the triumph of civic dignity and political morality over ideological monism, bureaucratic cynicism and police dictatorship.2 Rooted in an individualistic concept of freedom, programmatically skeptical of all ideological blueprints for social engineering, these revolutions were, at least in their first stage, liberal and non-utopian.3 The fact that 1 See Archie Brown, Seven Years that Changed the World: Perestroika in Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 157-189. In this paper I elaborate upon and revisit the main ideas I put them forward in my introduction to Vladimir Tismaneanu, ed., The Revolutions of 1989 (London and New York: Routledge, 1999) as well as in my book Reinventing Politics: Eastern Europe from Stalin to Havel (New York: Free Press, 1992; revised and expanded paperback, with new afterword, Free Press, 1993). -

Mainstreaming Radical Politics in Sri Lanka: the Case of JVP Post-1977

Mainstreaming Radical Politics in Sri Lanka: The case of JVP post-1977 Nirmal Ranjith Dewasiri Abstract This article provides a critical understanding of dynamics behind the roles of the People’s Liberation Front (JVP) in post-1977 Sri Lankan politics. Having suffered a severe setback in the early 1970s, the JVP transformed itself into a significant force in electoral politics that eventually brought the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) to power. This article explains the transformation by examining the radical political setting and mapping out the actors and various movements which allowed the JVP to emerge as a dominant player within the hegemonic political mainstream in Sri Lanka. Furthermore, it also highlights the structural changes in JVP politics and its challenges for future consolidation. Introduction The 1977 general election marked a major turning point in the history of post-colonial Sri Lanka. While the landslide victory of the United National Party (UNP) was the most important highlight of the election results, the shocking defeat for the old leftist parties was equally important. Both the victory of the UNP and the defeat of the left were symbolic. The left’s electoral defeat was soon followed by the introduction of new macro-economic policy framework under the UNP’s rule, which replaced protective economic policy framework that was endorsed by the Left.1 Ironically enough, as if to dig its own grave, the same UNP government helped People’s Liberation Front (JVP), which became a formidable threat to the smooth implementation of the new economic policies, to re-enter into the political mainstream by way of freeing its leadership from the prison. -

BOLSHEVISM at a DEADLOCK by Th~ Sam8 A11thor the Labour Revolutiol\ Translated by H

BOLSHEVISM AT A DEADLOCK By th~ sam8 A11thor The Labour Revolutiol\ Translated by H. J. STI!.NNING Crown 6vo "ExtreJnely intere-sting and sugg('stive. "-Star "An able stntcment."-AI~t~d((n Pms Joumal Foundations of Christianity A STUDY IN CHRISTIAN ORIOINS ROJ•al !lr•o "It is n very intt•rrsting nnd n vrry competent book, informed, nli\'c, and challenging from end to em!. "-E1posilory Timu BOLSHEVISM AT A DEADLOCK by KARL KAUTSKY Translated by B. PRITCHARD LONDON GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD :MUSEUM STREET The German original, "Der Bolschewismus in der Sackgassa" was first published in September 1930 FIRST PUBLISHED IN ENGLISH IN APRI~ 1931 All rigllls merued PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY UNWIN BROTHERS LTD., WOKlNG PREFACE When I began to write this book, the Kolhosi con· troversy was already · causing great excitement in Soviet Russia. Nothing has happened since to induce me to change my stafements. The most important event in Soviet Russia since the publication of the original German edition of this book is undoubtedly the monstrous comedy of the Moscow trial which began on Novem· her 25, 1930. It was directed against eight engineers, who were most unusually anxious not only to denounce themselves'as counter-revolutionaries and wreckers but ... also as unprincipled rascals. This trial clearly proved to anybody who could see, and who wished to see, that Stalin and his associates • expect the Five Year Plan to be a failure, and that they are already seeking for scapegoats on whom to put the blame. This trial, however, has not helped the present rulers of Soviet Russia; it has made their position only more precarious. -

SIBERIA and RUSSIA by SIBIRYAK

SIBERIA AND RUSSIA By SIBIRYAK The preceding article deals with the chances of II Red Siberia to eontintte the present war. The quest-ion arll1es: is there no possibility 0/ a White Siberia? To give an answer to this question frO-in a historical perspective we have reqllested a contribution frO'Jn a Russian who has been and still is 71LOSt intimcttelll connected with Siberia. a7ul who prefers to hide his ident'itll muler a pseudonllm. A large l'iterature, partie/tla'rlll in Russian, exists on Siberia and her role in the civ'il war that foll01lJed the Bolshevist revolution, but we aro not aware of a,ny art'iele that has eve'T 1Jresented in conc'ise form the historll of the Siberian autonomist movement in its relation to Russia and Bolshevism. OUT article ends with the Victo-TlI 0/ the Reds in Siberia in 19f!2; but the stnlggle for a White Sibe-ria has gone on ever since.-K.M. CORTEZ AND YERMAK Moscow, or the periphery that is Two great political events of the Siberia? sixteenth century, taking place on dif In the former case we have an im ferent continents, brought magnificent perialistic policy which regards Siberia results to the states in whose interests simply as a colony existing for the they were undertaken. These events needs of the metropolis, in the latter were the conquest of Central America by the development of an economic and Cortez and that of Siberia by Yermak. political program of the local Siberian Thanks to the efforts of these con population which, with its own pro quistadores, both typical adventurers moters and ideologists, became known eager to get as far away as possible from as the Siberian autonomist movement, the laws of their respective countries, or Siberian regionalism - Sibirskoye Spain and Moscovite Russia became Oblastnitchestvo. -

Jacques Camatte Community and Communism in Russia

Jacques Camatte Community and Communism in Russia Chapter I Chapter II Chapter III Chapter I Publishing Bordiga's texts on Russia and writing an introduction to them was rather repugnant to us. The Russian revolution and its involution are indeed some of the greatest events of our century. Thanks to them, a horde of thinkers, writers, and politicians are not unemployed. Among them is the first gang of speculators which asserts that the USSR is communist, the social relations there having been transformed. However, over there men live like us, alienation persists. Transforming the social relations is therefore insufficient. One must change man. Starting from this discovery, each has 'functioned' enclosed in his specialism and set to work to produce his sociological, ecological, biological, psychological etc. solution. Another gang turns the revolution to its account by proving that capitalism can be humanised and adapted to men by reducing growth and proposing an ethic of abstinence to them, contenting them with intellectual and aesthetic productions, restraining their material and affective needs. It sets computers to work to announce the apocalypse if we do not follow the advice of the enlightened capitalist. Finally there is a superseding gang which declares that there is neither capitalism nor socialism in the USSR, but a kind of mixture of the two, a Russian cocktail ! Here again the different sciences are set in motion to place some new goods on the over-saturated market. That is why throwing Bordiga into this activist whirlpool -

1992 a Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified 1992 A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France Citation: “A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France,” 1992, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Luo Guibo, "Wuchanjieji guojizhuyide guanghui dianfan: yi Mao Zedong he Yuan-Yue Kang-Fa" ("A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France"), in Mianhuai Mao Zedong (Remembering Mao Zedong), ed. Mianhuai Mao Zedong bianxiezhu (Beijing: Zhongyang Wenxian chubanshe, 1992) 286-299. Translated by Emily M. Hill http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/120359 Summary: Luo Guibo recounts China's involvement in the First Indochina War and its assistance to the Viet Minh. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation One Late in 1949, soon after the establishment of New China, Chairman Ho Chi Minh and the Central Committee of the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) wrote to Chairman Mao and the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), asking for Chinese assistance. In January 1950, Ho made a secret visit to Beijing to request Chinaʼs assistance in Vietnamʼs struggle against France. Following Hoʼs visit, the CCP Central Committee made the decision, authorized by Chairman Mao, to send me on a secret mission to Vietnam. I was formally appointed as the Liaison Representative of the CCP Central Committee to the ICP Central Committee. Comrade [Liu] Shaoqi personally composed a letter of introduction, which stated: ʻI hereby recommend to your office Comrade Luo Guibo, who has been a provincial Party secretary and commissar, as the Liaison Representative of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.