From Folk Source to Professional Creation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sofia Gubaidulina AUSSERDEM Prokofjew, Denissow, Kantscheli, Geringas, Chatschaturjan U.A

AUSGABE 1. 2020 GEBURTS- UND GEDENKTAGE 90. GEBURTSTAG 2021 Sofia Gubaidulina AUSSERDEM Prokofjew, Denissow, Kantscheli, Geringas, Chatschaturjan u.a. INHALT / CONTENT Liebe Leserinnen, 03 / 22 liebe Leser, Sofia Gubaidulina 90. Geburtstag im Jahr 2021 die russische Komponistin Jelena Firssowa sagte ein- 06 / 24 mal über die von ihr bewunderte Sofia Gubaidulina, Georgische Musik sie sei eine „Schamanin in der Musik”, eine der tief- des 20. Jahrhunderts gründigsten und interessantesten Komponistinnen Kantscheli, Zinzadse, der Gegenwart. Im Jahr 2021 begeht Gubaidulina Nassidse ihren 90. Geburtstag. In diesem Magazin, das Kompo- nistenjubiläen der bervorstehenden Jahre 2021 und 08 / 26 2022 zum Inhalt hat, berichten wir von neuesten Sergej Prokofjew Werken Gubaidulinas und veröffentlichen zudem ein zum 130. Geburtstag dieser Komponistin gewidmetes Exklusiv-Interview 12 mit dem Dirigenten Kent Nagano. 100. Geburtstage von Francisco Tanzer & Stanisław Lem Ein weiteres Jubiläum steht uns mit Sergej Prokof- jews 130. Geburtstag im April 2021 bevor. Wir ver- 14 / 29 binden einen Rückblick auf die spektakuläre Neuin- 10. Todestag von szenierung von Prokofjews Oper „Die Verlobung im Karen Chatschaturjan Kloster” an der Staatsoper Berlin 2019 mit Kurzdar- stellungen ausgewählter Werke. 15 / 29 Edison Denissow Der 25. Todestag des Russen Edison Denissow, aus- 25. Todestag am 24. November 2021 gewählte Gedenktage von Komponisten aus Georgien 18 / 30 und zwei 100. Geburtstage von bedeutenden Text- Jubiläen litauischer dichtern wie Stanisław Lem und Francisco Tanzer Interpreten und Komponisten sind weitere Themen dieser Ausgabe. David Geringas & Bronius Kutavičius Wir wünschen Ihnen eine interessante Lektüre und viele Entdeckungen, 20 / 32 News Winfried Jacobs 19 Geschäftsführer Geburts- und Kennen Sie auch die anderen Gedenktage 2021 Hefte des SIKORSKI Magazins? 21 Vorschau 2022 IMPRESSUM FOTONACHWEISE Titel Sofia Gubaidulina © Priska Ketterer S. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

Adjara Group Hospitality

CATALOGUE OF BUSINESS COOPERATION PROFILES OF COMPANIES BY SECTORS OPERATING IN GEORGIA October, 2019 www.eugbc.net Contents Energy, Oil & Gas.............................................................................................................................................. 4 Banks................................................................................................................................................................ 15 Free Industrial Zones & Investment Opportunities ......................................................................................... 19 Legal Services/Consulting/Auditing ................................................................................................................ 23 Tourism & Hospitality ..................................................................................................................................... 39 Food & Beverages/Animal Feed ...................................................................................................................... 49 Construction & Industrial Products ................................................................................................................. 58 Transport & Logistics ...................................................................................................................................... 69 Communications & IT ..................................................................................................................................... 75 Medicine & Insurance ..................................................................................................................................... -

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

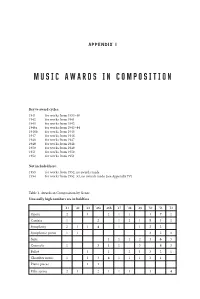

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

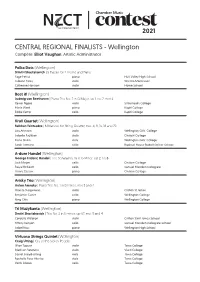

CENTRAL REGIONAL FINALISTS - Wellington Compère: Elliot Vaughan, Artistic Administrator

2021 CENTRAL REGIONAL FINALISTS - Wellington Compère: Elliot Vaughan, Artistic Administrator Polka Dots (Wellington) Dimitri Shostakovich | 5 Pieces for 2 Violins and Piano Sage Pettus piano Hutt Valley High School Aubane Farcy violin Wa Ora Montessori Catherine Harrison violin Home School Beet it! (Wellington) Ludwig van Beethoven | Piano Trio No. 2 in G Major, op 1, no 2, mvt 4 Xavier Ngaro violin St Bernard’s College Maria Ward piano Kapiti College Eddie Kemp cello Kapiti College Krull Quartet (Wellington) Sulkhan Tsintsadze | Miniatures for String Quartet, nos. 4, 9, 15, 18 and 20 Lisa Artmann violin Wellington Girls’ College Isabelle Faulkner violin Onslow College Fiona Quinn viola Wellington Girls’ College Sarah Artmann cello Raphael House Rudolf Steiner School A-dore Handel (Wellington) George Frideric Handel | Trio Sonata No. 16 in G Minor, op 2, no 8 Jack Moyer cello Onslow College Freya McKeich cello Samuel Marsden Collegiate Henry Zaslow piano Onslow College Arisky Trio (Wellington) Anton Arensky | Piano Trio No. 1 in D Minor, mvt 3 and 4 Shanita Sungsuwan violin Chilton St James Benjamin Carter cello Wellington College Ning Chin piano Wellington College Tri Muzykanta (Wellington) Dmitri Shostakovich | Trio No. 2 in E minor, op 67, mvt 3 and 4 Cordelia Waldron violin Chilton Saint James School Tiffany Kenyon cello Samuel Marsden Collegiate School Isabel Ross piano Wellington High School Virtuoso Strings Quintet (Wellington) Craig Utting | Cry of the Stolen People Jillian Tupuse violin Tawa College Madison Setefano violin Viard College Daniel Sneyd-Utting viola Tawa College Rochelle Pese Akerise viola Tawa College Veititi Alapati cello Tawa College. -

Sulkhan Tsintsadze Georgian Dance Khorumi Viola and Piano Sheet Music

Sulkhan Tsintsadze Georgian Dance Khorumi Viola And Piano Sheet Music Download sulkhan tsintsadze georgian dance khorumi viola and piano sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 5 pages partial preview of sulkhan tsintsadze georgian dance khorumi viola and piano sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 12618 times and last read at 2021-09-23 08:53:37. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of sulkhan tsintsadze georgian dance khorumi viola and piano you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Viola Solo, Piano Accompaniment Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Joshuas Glasgow A Suite Of Seven Pieces For String Quartet By Scottish Georgian Composer Joshua Campbell Joshuas Glasgow A Suite Of Seven Pieces For String Quartet By Scottish Georgian Composer Joshua Campbell sheet music has been read 3268 times. Joshuas glasgow a suite of seven pieces for string quartet by scottish georgian composer joshua campbell arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 08:31:00. [ Read More ] Georgian March Mvt Iv From Caucasian Sketches No 2 Opus 42 Georgian March Mvt Iv From Caucasian Sketches No 2 Opus 42 sheet music has been read 5149 times. Georgian march mvt iv from caucasian sketches no 2 opus 42 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-22 21:52:18. [ Read More ] Georgian National Anthem Tavisupleba For Brass Quintet Georgian National Anthem Tavisupleba For Brass Quintet sheet music has been read 4203 times. -

Lietuvos Muzikologija 20.Indd

Lietuvos muzikologija, t. 20, 2019 Nana SHARIKADZE Nana SHARIKADZE Georgian Musical Criticism of the Soviet and Post-Soviet Eras Gruzinų muzikos kritika sovietmečiu ir posovietiniu laikotarpiu V. Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire, Griboedov St. 8-10, 0108 Tbilisi, Georgia Email: [email protected] Abstract This article examines the problem of music criticism in Georgia during the Soviet and post-Soviet eras. Criticism and music criticism, in par- ticular, as an “art of discussion and analysis” became “destructive” and dangerous for totalitarian regimes. Authentic criticism was replaced by “quasi-criticism,” which was driven by the do’s and don’ts of the regime. Thus, the following issues are discussed in the article: how development of music criticism reflected the social-political changes in Georgia after occupation (since 1921) and to what extent musical processes have been influenced there. Consequently, attention is drawn to the decades from the 1920s to the 1950s and from the 1960s to the 1980s, and the situation is analyzed through the lens of Soviet aesthetics. In that regard, Grigory Orjonikidze’s works are identified as the most influential and mind-opening examples in the development of Georgian music criticism under Soviet rule. The reconsideration of music criticism became topical at the end of the last century (the late ‘90s, after the Soviet Union collapsed). In the postmodern reality, musical criticism had to rediscover its role, redesign its values, and regain its place through the perspective of both local and global realities. The following issues are discussed: the influence of the mass media; social media’s effects on the development of music criticism; and coexistence of “description-” as well as the “analysis-” based attitude towards the musical processes. -

2015 Program Book

MAY 8, 9 & 10, 2015 DeBartolo Performing Arts Center University of Notre Dame Forty-second Annual 2014 Grand Prize Winner, Telegraph Quartet National Chamber Music Competition AMERICA’S PREMIER EDUCATIONAL CHAMBER MUSIC COMPETITION Welcome to the Fischoff Elected Officials Letters .......................................................2-3 President and Artistic Director Letters .................................... 4 Board of Directors ................................................................... 5 2014 Senior Wind Division Gold Medal Winner, Akropolis Reed Quintet Welcome to Notre Dame Letter from Father Jenkins ....................................................... 6 Campus Map ........................................................................... 7 The Fischoff National Chamber Music Association History, Mission and Financial Retrospective ......................... 8 Staff and Competition Staff .................................................... 9 National Advisory Council ..............................................10-11 Educator Award Residency .............................................. 12-13 Double Gold Tours ...........................................................14-15 Emilia Romagna Festival ........................................................ 17 Chamber Music Mentoring Project .................................18-19 Peer Ambassadors for Chamber Music (PACMan) .............. 20 The 42nd Annual Fischoff Competition 2014 Junior Gold Medal Winner, Quartet Fuoco History of the Competition ................................................. -

The Komitas Legacy: Armenian Piano Trios

THE KOMITAS LEGACY: ARMENIAN PIANO TRIOS Arno Babajanian (Yerevan, 1921–Moscow, 1983) Piano Trio in F sharp minor (1952) 25:15 Dedicated to David Oistrakh and Sviatoslav Knushevitsky 1 I Largo 10:32 2 II Andante 7:11 3 III Allegro vivace 7:32 (Soghomon Soghomonian) Komitas (Kütahya, Turkey, 1869–Paris, 1935) Six Armenian Miniatures* 21:06 arranged (2016) for piano trio by Varoujan Bartikian 4 Shogher jan (‘Dear Shogher’) 3:56 5 Chinar es (‘You are as slender as a plane-tree’) 3:28 6 Hov arek (‘Give me a cool breeze’) 2:30 7 Krunk (‘The Crane’) 4:18 8 Dzayn tour, ov tsovak (‘Dear lake, answer me’) 4:10 9 Kele kele (‘Let’s walk’) 2:44 Nina Grigoryan (Derzhavinsk, Kazakhstan, 1976) Aeternus (2018)* 10:35 Dedicated to Trio Aeternus 10 I Andante maestoso 3:37 11 II Allegro con brio 2:25 12 III Andante spiritoso 4:33 2 Ardashes Agoshian (Istanbul, Turkey, 1977) Piano Trio, Homage to Komitas (2017)* 21:55 Dedicated to Trio Aeternus 13 I Broken Bells – 2:54 14 II Broken Dance – 1:15 15 III Possession (Shamanioso) – 0:58 16 IV Deus Internus – 6:53 17 V Broken Dance 2 – 2:43 18 VI Sitie (‘Thirst’) 7:12 Trio Aeternus TT 78:53 Alexander Stewart, violin Varoujan Bartikian, cello *FIRST RECORDINGS João Paulo Santos, piano 3 THE KOMITAS LEGACY: ARMENIAN PIANO TRIOS by William Melton Komitas (Gomidas) Vardapet bore the name Soghomon Soghomonian after his birth in the city of Kütahya in western Turkey on 8 October 1869. His father, Kevork, was a cobbler, but he and his wife, Takuhi, also cultivated poetry and music. -

15Th Annual International Student Concert

Monday, April 19, 2021 | 7:30 PM Livestreamed from Gordon K. and Harriet Greenfield Hall and William R. and Irene D. Miller Recital Hall 15th Annual International Student Concert PROGRAM PANCHO VLADIGEROV Three pieces, Op. 15 (1899–1978) I. Prélude III. Humoresque Lulwa Al Shamlan (Kuwaiti and Bulgarian) Pancho Vladigerov was a prominent and influential Bulgarian composer, known for combining Bulgarian folk music with classical music. The Prélude and Humoresque from this suite shows Vladigerov’s range in style. However, what they share is a nationalistic melody. The Humoresque uses elements typically heard in Bulgarian folk music, while the Prélude has a post-Romantic style that was very popular with composers in Eastern Europe and Russia at the time it was composed. Lulwa Al Shamlan is a half Kuwaiti, half Bulgarian pianist. She started learning piano at age four, and at age eight, was accepted to the Wells Cathedral School, one of the four specialized music schools in the U.K. From a young age, Lulwa has traversed the world, performing in the Middle East, Europe, the U.S.A., and Central Asia. Notable performances include her concert with the Uzbekistan State Symphony Orchestra, where she played Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in 2019; solo recitals at Dar Al Athar, Kuwait in 2017 and 2019; and winners’ recitals of various competitions in Weill Recital Hall and Zankel Hall at Carnegie Hall in 2014, 2016, and 2020. A few of Lulwa’s achievements include winning the award for most outstanding pianist at the Mid- Somerset Festival in the U.K. -

Sulkhan Tsintsadze Georgian Dance Khorumi Viola and Piano Sheet Music

Sulkhan Tsintsadze Georgian Dance Khorumi Viola And Piano Sheet Music Download sulkhan tsintsadze georgian dance khorumi viola and piano sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 5 pages partial preview of sulkhan tsintsadze georgian dance khorumi viola and piano sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 26874 times and last read at 2021-10-01 09:42:41. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of sulkhan tsintsadze georgian dance khorumi viola and piano you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Viola Solo, Piano Accompaniment Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Intermediate [ Read Sheet Music ] Other Sheet Music Joshuas Glasgow A Suite Of Seven Pieces For String Quartet By Scottish Georgian Composer Joshua Campbell Joshuas Glasgow A Suite Of Seven Pieces For String Quartet By Scottish Georgian Composer Joshua Campbell sheet music has been read 10907 times. Joshuas glasgow a suite of seven pieces for string quartet by scottish georgian composer joshua campbell arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-30 09:50:51. [ Read More ] Georgian March Mvt Iv From Caucasian Sketches No 2 Opus 42 Georgian March Mvt Iv From Caucasian Sketches No 2 Opus 42 sheet music has been read 11758 times. Georgian march mvt iv from caucasian sketches no 2 opus 42 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-29 14:54:26. [ Read More ] Georgian National Anthem Tavisupleba For Brass Quintet Georgian National Anthem Tavisupleba For Brass Quintet sheet music has been read 10581 times. -

Book Domitille Coppey

Domitille Coppey Violoncelliste Dossier Curriculum Vitae Qualifications Concerts et festivals Enregistrements Activité pédagogique Presse! Répertoire! Recommandations Références www.domitillecoppey.com 1 Domitille Coppey Avenue Vinet 12 CH- 1004 LAUSANNE cell. +41 78 843 81 25 [email protected] www.domitillecoppey.com www.duocoppey.com www.4ygrecs.com née le 22 juillet 1989 à Sion, originaire de Vétroz - Valais - Suisse Curriculum Vitae Issue d'une famille d'artistes persuadés que la complémentarité aide au développement de la personnalité et que la musique peut apporter cette richesse, Domitille Coppey a suivi dès son plus jeune âge une formation musicale vivante et variée lui ayant donné une expérience large de la scène et de l'art en général, ainsi qu'une formation académique structurée, mêlée à la conduite de nomBreux projets divers, tant artistiques que pédagogiques, faisant d'elle une personnalité complète, polyvalente et compétente à de multiples niveaux. Baignée dès sa naissance dans les pédagogies actives Willems et Orff par sa mère Nicole Coppey, elle reçoit très tôt une solide formation musicale de base, et continuera d'exploiter ces approches actives durant tout son cursus musical, notamment à travers la percussion corporelle. DéButant l'étude du violoncelle à 4 ans ainsi que celle du piano l'année suivante, elle obtient à 14 ans, sous la conduite de Philippe Mermoud, son Certificat de violoncelle avec mention «Excellent et félicitations du jury». Elle reçoit le soutien de la Fondation Irène Dénéréaz et poursuit ses études avec Pascal Michel, violoncelle solo de l’Orchestre de ChamBre de Genève. Elle passe son Diplôme DipABRSM « with Distinction », et oBtient également « with Distinction » la Licence de violoncelle LRSM de l'Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music de Londres à 18 ans.