GRECHANINOV Complete Music for Viola and Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sofia Gubaidulina AUSSERDEM Prokofjew, Denissow, Kantscheli, Geringas, Chatschaturjan U.A

AUSGABE 1. 2020 GEBURTS- UND GEDENKTAGE 90. GEBURTSTAG 2021 Sofia Gubaidulina AUSSERDEM Prokofjew, Denissow, Kantscheli, Geringas, Chatschaturjan u.a. INHALT / CONTENT Liebe Leserinnen, 03 / 22 liebe Leser, Sofia Gubaidulina 90. Geburtstag im Jahr 2021 die russische Komponistin Jelena Firssowa sagte ein- 06 / 24 mal über die von ihr bewunderte Sofia Gubaidulina, Georgische Musik sie sei eine „Schamanin in der Musik”, eine der tief- des 20. Jahrhunderts gründigsten und interessantesten Komponistinnen Kantscheli, Zinzadse, der Gegenwart. Im Jahr 2021 begeht Gubaidulina Nassidse ihren 90. Geburtstag. In diesem Magazin, das Kompo- nistenjubiläen der bervorstehenden Jahre 2021 und 08 / 26 2022 zum Inhalt hat, berichten wir von neuesten Sergej Prokofjew Werken Gubaidulinas und veröffentlichen zudem ein zum 130. Geburtstag dieser Komponistin gewidmetes Exklusiv-Interview 12 mit dem Dirigenten Kent Nagano. 100. Geburtstage von Francisco Tanzer & Stanisław Lem Ein weiteres Jubiläum steht uns mit Sergej Prokof- jews 130. Geburtstag im April 2021 bevor. Wir ver- 14 / 29 binden einen Rückblick auf die spektakuläre Neuin- 10. Todestag von szenierung von Prokofjews Oper „Die Verlobung im Karen Chatschaturjan Kloster” an der Staatsoper Berlin 2019 mit Kurzdar- stellungen ausgewählter Werke. 15 / 29 Edison Denissow Der 25. Todestag des Russen Edison Denissow, aus- 25. Todestag am 24. November 2021 gewählte Gedenktage von Komponisten aus Georgien 18 / 30 und zwei 100. Geburtstage von bedeutenden Text- Jubiläen litauischer dichtern wie Stanisław Lem und Francisco Tanzer Interpreten und Komponisten sind weitere Themen dieser Ausgabe. David Geringas & Bronius Kutavičius Wir wünschen Ihnen eine interessante Lektüre und viele Entdeckungen, 20 / 32 News Winfried Jacobs 19 Geschäftsführer Geburts- und Kennen Sie auch die anderen Gedenktage 2021 Hefte des SIKORSKI Magazins? 21 Vorschau 2022 IMPRESSUM FOTONACHWEISE Titel Sofia Gubaidulina © Priska Ketterer S. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

From Folk Source to Professional Creation

GESJ: Musicology and Cultural Science 2019|No.1(19) ISSN 1512-2018 UDC - 78 FROM FOLK SOURCE TO PROFESSIONAL CREATION: ON ONE TUSHETIAN TUNE Zumbadze Natalia, Matiashvili Ketevan Vano Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire, 8-10 Griboedov st. Summary: The article discusses the distribution area and development of one Tushetian tune mostly known as Mtsqemsuri. Today unison performance of this polyphonic melody, by nature, is explained as a decline of the process of Georgian traditional polyphonic thinking. The article also touches upon the examples of academic music, folk-jazz, author’s folklore, popular genre, which are successful or unsuccessful attempts of arranging the folk source. Keywords: Georgian (Tushetian) music, mtsqemsuri, Arjevnishvili, Tsintsadze, Erkomaishvili, Ebralidze. When researching Georgian-North Caucasian parallels in addition to archival materials preserved at the Georgian Folk Music Laboratory we got familiarized with the audio recordings copied by ethnomusicologist Manana Shilakadze from the archives of Dagestan State Television and Radio Committee in 1981. These included a panduri piece entitled “Georgian motive” performed by renowned Avarian folk professional Ramazan Magomedov (audio ex. N1). This is the tune that Sulkhan Tsintsadze used in one of his quartet miniatures “Mtsqemsuri” (Shepherd’s song), which is the final fifth part (Simghera; Gaprindi, shavo mertskhalo; Satsekvao; Khumroba, Mtsqemsuri) of the quartet suite composed in 1951 (audio ex. N2). Sulkhan Tsintsadze’s miniatures are more or less discussed in musicological literature. All authors unanimously recognize their folk basis, but the specific source of Mtsqemsuri is not indicated anywhere [1:47]; [2:107, 111]; [3:74, 75, 90, 94]. The notated version of the tune published by the Republican House of Folk Art in 1964 is entitled Tushuri satrpialo (Tushetian love song), with well-known singer, choir master and virtuoso panduri player Mariam Arjevnishvili (1918-1958) indicated as the author (her husband Geronti Tughushi is the author of the verbal text) (notated ex. -

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One 1 Ballade, Op. 49 (1939, rev. 1958)* 9:40 Romantic Episodes, Op. 88 (1962) 19:39 15 No. 1 Moderato 1:38 Four Narratives, Op. 48 (1939)* 11:25 16 No. 2 Allegro molto 1:15 2 No. 1 Andante 3:12 17 No. 3 Sostenuto, severo 3:35 3 No. 2 ‘What the sea spoke about 18 No. 4 Andantino, molto grazioso during the storm’: e rubato 0:57 Allegro impetuoso 2:00 19 No. 5 Allegro 0:49 4 No. 3 ‘What the sea spoke of on the 20 No. 6 Adagio, cantabile 3:19 morning after the storm’: 21 No. 7 Andante 1:48 Andantino, un poco con moto 3:48 22 No. 8 Allegro giocoso 2:47 5 No. 4 ‘In memory of A. M. Dianov’: 23 No. 9 Sostenuto, lugubre 1:35 Andante, molto cantabile 2:25 24 No. 10 Tempestoso e maestoso 1:56 Piano Sonata No. 8 in B flat, Op. 50 TT 71:01 (1939–44)** 15:00 6 I Allegretto giocoso 4:21 Kyung-Ah Noh, piano 7 II Andante cantabile e pensieroso 3:24 8 III Energico. Con moto assai 7:15 *FIRST RECORDING; **FIRST RECORDING ON CD Echoes of the Theatre, Op. 60 (mid-1940s)* 14:59 9 No. 1 Aria: Adagio molto cantabile 2:27 10 No. 2 Galliarde and Pavana: Vivo 3:20 11 No. 3 Chorale and Polka: Andante 2:57 12 No. 4 Waltz: Tempo di valse tranquillo 1:32 13 No. 5 Dances in the Square and Siciliana: Quasi improvisata – Allegretto 2:24 14 No. -

Bitstream 46447.Pdf

I/2021 Музичка критика у Русији и Источној Европи У знак сећања на Стјуарта Кембела (1949–2018) Music Criticism in Russia and Eastern Europe In memoriam Stuart Campbell (1949–2018) Гост уредник Ивана Медић Guest Editor Ivana Medić Музикологија Часопис Музиколошког института САНУ Musicology Jоurnal of the Institute of Musicology SASA ~ 30 (I/2021) ~ ГЛАВНИ И ОДГОВОРНИ УРЕДНИК / EDITOR-IN-CHIЕF Александар Васић / Aleksandar Vasić РЕДАКЦИЈА / ЕDITORIAL BOARD Ивана Весић, Јелена Јовановић, Данка Лајић Михајловић, Ивана Медић, Биљана Милановић, Весна Пено, Катарина Томашевић / Ivana Vesić, Jelena Jovanović, Danka Lajić Mihajlović, Ivana Medić, Biljana Milanović, Vesna Peno, Katarina Tomašević СЕКРЕТАР РЕДАКЦИЈЕ / ЕDITORIAL ASSISTANT Милош Браловић / Miloš Bralović МЕЂУНАРОДНИ УРЕЂИВАЧКИ САВЕТ / INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL COUNCIL Светислав Божић (САНУ), Џим Семсон (Лондон), Алберт ван дер Схоут (Амстердам), Јармила Габријелова (Праг), Разија Султанова (Лондон), Денис Колинс (Квинсленд), Сванибор Петан (Љубљана), Здравко Блажековић (Њујорк), Дејв Вилсон (Велингтон), Данијела Ш. Берд (Кардиф) / Svetislav Božić (SASA), Jim Samson (London), Albert van der Schoot (Amsterdam), Jarmila Gabrijelova (Prague), Razia Sultanova (Cambridge), Denis Collins (Queensland), Svanibor Pettan (Ljubljana), Zdravko Blažeković (New York), Dave Wilson (Wellington), Danijela S. Beard (Cardiff) Музикологија је рецензирани научни часопис у издању Музиколошког института САНУ. Посвећен је проучавању музике као естетског, културног, историјског и друштвеног феномена и примарно усмерен на музиколошка и етномузиколошка истраживања. Редакција такође прихвата интердисциплинарне радове у чијем је фокусу музика. Часопис излази два пута годишње. Упутства за ауторе се могу преузети овде: https://music.sanu.ac.rs/en/instructions-for-authors/ Musicology is a peer-reviewed journal published by the Institute of Musicology SASA (Belgrade). It is dedicated to the research of music as an aesthetical, cultural, historical and social phenomenon and primarily focused on musicological and ethnomusicological research. -

Adjara Group Hospitality

CATALOGUE OF BUSINESS COOPERATION PROFILES OF COMPANIES BY SECTORS OPERATING IN GEORGIA October, 2019 www.eugbc.net Contents Energy, Oil & Gas.............................................................................................................................................. 4 Banks................................................................................................................................................................ 15 Free Industrial Zones & Investment Opportunities ......................................................................................... 19 Legal Services/Consulting/Auditing ................................................................................................................ 23 Tourism & Hospitality ..................................................................................................................................... 39 Food & Beverages/Animal Feed ...................................................................................................................... 49 Construction & Industrial Products ................................................................................................................. 58 Transport & Logistics ...................................................................................................................................... 69 Communications & IT ..................................................................................................................................... 75 Medicine & Insurance ..................................................................................................................................... -

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

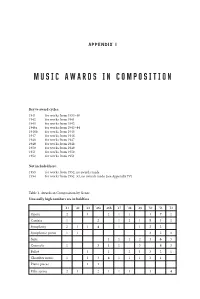

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

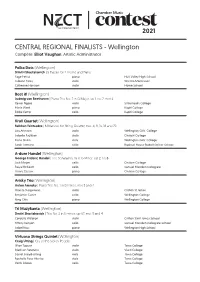

CENTRAL REGIONAL FINALISTS - Wellington Compère: Elliot Vaughan, Artistic Administrator

2021 CENTRAL REGIONAL FINALISTS - Wellington Compère: Elliot Vaughan, Artistic Administrator Polka Dots (Wellington) Dimitri Shostakovich | 5 Pieces for 2 Violins and Piano Sage Pettus piano Hutt Valley High School Aubane Farcy violin Wa Ora Montessori Catherine Harrison violin Home School Beet it! (Wellington) Ludwig van Beethoven | Piano Trio No. 2 in G Major, op 1, no 2, mvt 4 Xavier Ngaro violin St Bernard’s College Maria Ward piano Kapiti College Eddie Kemp cello Kapiti College Krull Quartet (Wellington) Sulkhan Tsintsadze | Miniatures for String Quartet, nos. 4, 9, 15, 18 and 20 Lisa Artmann violin Wellington Girls’ College Isabelle Faulkner violin Onslow College Fiona Quinn viola Wellington Girls’ College Sarah Artmann cello Raphael House Rudolf Steiner School A-dore Handel (Wellington) George Frideric Handel | Trio Sonata No. 16 in G Minor, op 2, no 8 Jack Moyer cello Onslow College Freya McKeich cello Samuel Marsden Collegiate Henry Zaslow piano Onslow College Arisky Trio (Wellington) Anton Arensky | Piano Trio No. 1 in D Minor, mvt 3 and 4 Shanita Sungsuwan violin Chilton St James Benjamin Carter cello Wellington College Ning Chin piano Wellington College Tri Muzykanta (Wellington) Dmitri Shostakovich | Trio No. 2 in E minor, op 67, mvt 3 and 4 Cordelia Waldron violin Chilton Saint James School Tiffany Kenyon cello Samuel Marsden Collegiate School Isabel Ross piano Wellington High School Virtuoso Strings Quintet (Wellington) Craig Utting | Cry of the Stolen People Jillian Tupuse violin Tawa College Madison Setefano violin Viard College Daniel Sneyd-Utting viola Tawa College Rochelle Pese Akerise viola Tawa College Veititi Alapati cello Tawa College. -

Sulkhan Tsintsadze Georgian Dance Khorumi Viola and Piano Sheet Music

Sulkhan Tsintsadze Georgian Dance Khorumi Viola And Piano Sheet Music Download sulkhan tsintsadze georgian dance khorumi viola and piano sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 5 pages partial preview of sulkhan tsintsadze georgian dance khorumi viola and piano sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 12618 times and last read at 2021-09-23 08:53:37. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of sulkhan tsintsadze georgian dance khorumi viola and piano you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Viola Solo, Piano Accompaniment Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Joshuas Glasgow A Suite Of Seven Pieces For String Quartet By Scottish Georgian Composer Joshua Campbell Joshuas Glasgow A Suite Of Seven Pieces For String Quartet By Scottish Georgian Composer Joshua Campbell sheet music has been read 3268 times. Joshuas glasgow a suite of seven pieces for string quartet by scottish georgian composer joshua campbell arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 08:31:00. [ Read More ] Georgian March Mvt Iv From Caucasian Sketches No 2 Opus 42 Georgian March Mvt Iv From Caucasian Sketches No 2 Opus 42 sheet music has been read 5149 times. Georgian march mvt iv from caucasian sketches no 2 opus 42 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-22 21:52:18. [ Read More ] Georgian National Anthem Tavisupleba For Brass Quintet Georgian National Anthem Tavisupleba For Brass Quintet sheet music has been read 4203 times. -

Lietuvos Muzikologija 20.Indd

Lietuvos muzikologija, t. 20, 2019 Nana SHARIKADZE Nana SHARIKADZE Georgian Musical Criticism of the Soviet and Post-Soviet Eras Gruzinų muzikos kritika sovietmečiu ir posovietiniu laikotarpiu V. Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire, Griboedov St. 8-10, 0108 Tbilisi, Georgia Email: [email protected] Abstract This article examines the problem of music criticism in Georgia during the Soviet and post-Soviet eras. Criticism and music criticism, in par- ticular, as an “art of discussion and analysis” became “destructive” and dangerous for totalitarian regimes. Authentic criticism was replaced by “quasi-criticism,” which was driven by the do’s and don’ts of the regime. Thus, the following issues are discussed in the article: how development of music criticism reflected the social-political changes in Georgia after occupation (since 1921) and to what extent musical processes have been influenced there. Consequently, attention is drawn to the decades from the 1920s to the 1950s and from the 1960s to the 1980s, and the situation is analyzed through the lens of Soviet aesthetics. In that regard, Grigory Orjonikidze’s works are identified as the most influential and mind-opening examples in the development of Georgian music criticism under Soviet rule. The reconsideration of music criticism became topical at the end of the last century (the late ‘90s, after the Soviet Union collapsed). In the postmodern reality, musical criticism had to rediscover its role, redesign its values, and regain its place through the perspective of both local and global realities. The following issues are discussed: the influence of the mass media; social media’s effects on the development of music criticism; and coexistence of “description-” as well as the “analysis-” based attitude towards the musical processes. -

FROM the RUSSIAN MUSICAL HERITAGE Evseyev Taneyev

Evseyev Taneyev Tchaikovsky Wielhorski Davydov Nikolayeva FROM THE RUSSIAN MUSICAL HERITAGE Natalia Zagorinskaya, soprano Alexander Zagorinsky, cello Marina Evseyeva, piano SMC CD 0137 DDD/STEREO TT: 79.51 Sergey Vasilyevich Evseyev (1894 – 1956) Karl Yulyevich Davydov (1838 – 1889) 1 Sonate dramatique for Cello and Piano in C minor, ор. 38 10.46 15 “By the Fountain” for Cello and Piano in D major, op. 20 No. 2 4.22 Four Songs, ор. 1 Tatiana Petrovna Nikolayeva (1924 – 1993) 2 “It is tiresome and sad ” ( Mikhail Lermontov ) 3.06 3 “Dedication ” ( Mikhail Lermontov ) 2.02 16 Poem for Cello and Piano in E flat major, op. 20 8.22 4 “Russian Song ” ( Spiridon Drozhzhin ) 2.34 5 “Night ” ( K.R. – Konstantin Romanov ) 2.08 Natalia Zagorinskaya, soprano 6 Nocturne for Cello and Piano in A major, op. 68 5.08 Alexander Zagorinsky, cello 7 Sonata No.1 for Piano in G major, op. 2 6.30 Marina Evseyeva, piano Sergey Ivanovich Taneyev (1856 – 1915) Recorded at the Small Hall of the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory, 8 Adagio cantabile from the Sonata for Violin and Piano in A minor 8.05 February – April, 2012 (arrangement for Cello and Piano by A. Egorov) Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893) 9 “The Lights in the Rooms were Already Dimmed”, op. 63 No. 5 (K.R.) 2.36 Sound engineer: Mikhail Spassky 10 “I Wished to Say one Single Word” (Lev Mey, from Heinrich Heine) 1.46 Editing and mastering: Mikhail Spassky 11 “Charmer”, op. 65 No. 6 (Paul Collin, translated by A. Gorchakova) 1.24 Recording engineers: Svetlana Spasskaya, Andrey Lebedev 12 “Night”, op. -

2015 Program Book

MAY 8, 9 & 10, 2015 DeBartolo Performing Arts Center University of Notre Dame Forty-second Annual 2014 Grand Prize Winner, Telegraph Quartet National Chamber Music Competition AMERICA’S PREMIER EDUCATIONAL CHAMBER MUSIC COMPETITION Welcome to the Fischoff Elected Officials Letters .......................................................2-3 President and Artistic Director Letters .................................... 4 Board of Directors ................................................................... 5 2014 Senior Wind Division Gold Medal Winner, Akropolis Reed Quintet Welcome to Notre Dame Letter from Father Jenkins ....................................................... 6 Campus Map ........................................................................... 7 The Fischoff National Chamber Music Association History, Mission and Financial Retrospective ......................... 8 Staff and Competition Staff .................................................... 9 National Advisory Council ..............................................10-11 Educator Award Residency .............................................. 12-13 Double Gold Tours ...........................................................14-15 Emilia Romagna Festival ........................................................ 17 Chamber Music Mentoring Project .................................18-19 Peer Ambassadors for Chamber Music (PACMan) .............. 20 The 42nd Annual Fischoff Competition 2014 Junior Gold Medal Winner, Quartet Fuoco History of the Competition .................................................