Toccata Classics TOCC0186 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Musical Partnership of Sergei Prokofiev And

THE MUSICAL PARTNERSHIP OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AND MSTISLAV ROSTROPOVICH A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PERFORMANCE BY JIHYE KIM DR. PETER OPIE - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2011 Among twentieth-century composers, Sergei Prokofiev is widely considered to be one of the most popular and important figures. He wrote in a variety of genres, including opera, ballet, symphonies, concertos, solo piano, and chamber music. In his cello works, of which three are the most important, his partnership with the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was crucial. To understand their partnership, it is necessary to know their background information, including biographies, and to understand the political environment in which they lived. Sergei Prokofiev was born in Sontovka, (Ukraine) on April 23, 1891, and grew up in comfortable conditions. His father organized his general education in the natural sciences, and his mother gave him his early education in the arts. When he was four years old, his mother provided his first piano lessons and he began composition study as well. He studied theory, composition, instrumentation, and piano with Reinhold Glière, who was also a composer and pianist. Glière asked Prokofiev to compose short pieces made into the structure of a series.1 According to Glière’s suggestion, Prokofiev wrote a lot of short piano pieces, including five series each of 12 pieces (1902-1906). He also composed a symphony in G major for Glière. When he was twelve years old, he met Glazunov, who was a professor at the St. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008). -

Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin's Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowsk

Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin’s Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowski BMUS, University of Victoria, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Music Monika Zaborowski, 2013 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin’s Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowski BMUS, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Susan Lewis-Hammond, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Bruce Vogt, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Michelle Fillion, (School of Music) Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Susan Lewis-Hammond, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Bruce Vogt, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Michelle Fillion, (School of Music) Departmental Member One of the major problems faced by performers of Chopin’s mazurkas is recapturing the elements that Chopin drew from Polish folk music. Although scholars from around 1900 exaggerated Chopin’s quotation of Polish folk tunes in their mixed agendas that related ‘Polishness’ to Chopin, many of the rudimentary and more complex elements of Polish folk music are present in his compositions. These elements affect such issues as rhythm and meter, tempo and tempo fluctuation, repetitive motives, undulating melodies, function of I and V harmonies. During his vacations in Szafarnia in the Kujawy region of Central Poland in his late teens, Chopin absorbed aspects of Kujaw performing traditions which served as impulses for his compositions. -

Vi Saint Petersburg International New Music Festival Artistic Director: Mehdi Hosseini

VI SAINT PETERSBURG INTERNATIONAL NEW MUSIC FESTIVAL ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: MEHDI HOSSEINI 21 — 25 MAY, 2019 facebook.com/remusik.org vk.com/remusikorg youtube.com/user/remusikorg twitter.com/remusikorg instagram.com/remusik_org SPONSORS & PARTNERS GENERAL PARTNERS 2019 INTERSECTIO A POIN OF POIN A The Organizing Committee would like to express its thanks and appreciation for the support and assistance provided by the following people: Eltje Aderhold, Karina Abramyan, Anna Arutyunova, Vladimir Begletsov, Alexander Beglov, Sylvie Bermann, Natalia Braginskaya, Denis Bystrov, Olga Chukova, Evgeniya Diamantidi, Valery Fokin, Valery Gergiev, Regina Glazunova, Andri Hardmeier, Alain Helou, Svetlana Ibatullina, Maria Karmanovskaya, Natalia Kopich, Roger Kull, Serguei Loukine, Anastasia Makarenko, Alice Meves, Jan Mierzwa, Tatiana Orlova, Ekaterina Puzankova, Yves Rossier, Tobias Roth Fhal, Olga Shevchuk, Yulia Starovoitova, Konstantin Sukhenko, Anton Tanonov, Hans Timbremont, Lyudmila Titova, Alexei Vasiliev, Alexander Voronko, Eva Zulkovska. 1 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall 4 Masterskaya M. K. Anikushina FESTIVAL CALENDAR Dekabristov St., 37 Vyazemsky Ln., 8 mariinsky.ru vk.com/sculptorstudio 2 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre 5 “Lumiere Hall” creative space TUESDAY / 21.05 19:00 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall Fontanka River Embankment 49, Lit A Obvodnogo Kanala emb., 74А ensemble für neue musik zürich (Switzerland) alexandrinsky.ru lumierehall.ru 3 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov 6 The Concert Hall “Jaani Kirik” Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Dekabristov St., 54A Glinka St., 2, Lit A jaanikirik.ru WEDNESDAY / 22.05 13:30 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov conservatory.ru Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Composer meet-and-greet: Katharina Rosenberger (Switzerland) 16:00 Lumiere Hall Marcus Weiss, Saxophone (Switzerland) Ensemble for New Music Tallinn (Estonia) 20:00 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre Around the Corner (Spain, Switzerland) 4 Vyazemsky Ln. -

5. Calling for International Solidarity: Hanns Eisler’S Mass Songs in the Soviet Union

From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry 2014 Abstract Group songs with direct political messages rose to enormous popularity during the interwar period (1918-1939), particularly in recently-defeated Germany and in the newly- established Soviet Union. This dissertation explores the musical relationship between these two troubled countries and aims to explain the similarities and differences in their approaches to collective singing. The discussion of the very complex and problematic relationship between the German left and the Soviet government sets the framework for the analysis of music. Beginning in late 1920s, as a result of Stalin’s abandonment of the international revolutionary cause, the divergences between the policies of the Soviet government and utopian aims of the German communist party can be traced in the musical propaganda of both countries. -

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One 1 Ballade, Op. 49 (1939, rev. 1958)* 9:40 Romantic Episodes, Op. 88 (1962) 19:39 15 No. 1 Moderato 1:38 Four Narratives, Op. 48 (1939)* 11:25 16 No. 2 Allegro molto 1:15 2 No. 1 Andante 3:12 17 No. 3 Sostenuto, severo 3:35 3 No. 2 ‘What the sea spoke about 18 No. 4 Andantino, molto grazioso during the storm’: e rubato 0:57 Allegro impetuoso 2:00 19 No. 5 Allegro 0:49 4 No. 3 ‘What the sea spoke of on the 20 No. 6 Adagio, cantabile 3:19 morning after the storm’: 21 No. 7 Andante 1:48 Andantino, un poco con moto 3:48 22 No. 8 Allegro giocoso 2:47 5 No. 4 ‘In memory of A. M. Dianov’: 23 No. 9 Sostenuto, lugubre 1:35 Andante, molto cantabile 2:25 24 No. 10 Tempestoso e maestoso 1:56 Piano Sonata No. 8 in B flat, Op. 50 TT 71:01 (1939–44)** 15:00 6 I Allegretto giocoso 4:21 Kyung-Ah Noh, piano 7 II Andante cantabile e pensieroso 3:24 8 III Energico. Con moto assai 7:15 *FIRST RECORDING; **FIRST RECORDING ON CD Echoes of the Theatre, Op. 60 (mid-1940s)* 14:59 9 No. 1 Aria: Adagio molto cantabile 2:27 10 No. 2 Galliarde and Pavana: Vivo 3:20 11 No. 3 Chorale and Polka: Andante 2:57 12 No. 4 Waltz: Tempo di valse tranquillo 1:32 13 No. 5 Dances in the Square and Siciliana: Quasi improvisata – Allegretto 2:24 14 No. -

The War to End War — the Great War

GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE GIVING WAR A CHANCE, THE NEXT PHASE: THE WAR TO END WAR — THE GREAT WAR “They fight and fight and fight; they are fighting now, they fought before, and they’ll fight in the future.... So you see, you can say anything about world history.... Except one thing, that is. It cannot be said that world history is reasonable.” — Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoevski NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND “Fiddle-dee-dee, war, war, war, I get so bored I could scream!” —Scarlet O’Hara “Killing to end war, that’s like fucking to restore virginity.” — Vietnam-era protest poster HDT WHAT? INDEX THE WAR TO END WAR THE GREAT WAR GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1851 October 2, Thursday: Ferdinand Foch, believed to be the leader responsible for the Allies winning World War I, was born. October 2, Thursday: PM. Some of the white Pines on Fair Haven Hill have just reached the acme of their fall;–others have almost entirely shed their leaves, and they are scattered over the ground and the walls. The same is the state of the Pitch pines. At the Cliffs I find the wasps prolonging their short lives on the sunny rocks just as they endeavored to do at my house in the woods. It is a little hazy as I look into the west today. The shrub oaks on the terraced plain are now almost uniformly of a deep red. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE WAR TO END WAR THE GREAT WAR GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1914 World War I broke out in the Balkans, pitting Britain, France, Italy, Russia, Serbia, the USA, and Japan against Austria, Germany, and Turkey, because Serbians had killed the heir to the Austrian throne in Bosnia. -

Behind the Scenes of the Fiery Angel: Prokofiev's Character

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ASU Digital Repository Behind the Scenes of The Fiery Angel: Prokofiev's Character Reflected in the Opera by Vanja Nikolovski A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved March 2018 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Brian DeMaris, Chair Jason Caslor James DeMars Dale Dreyfoos ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 ABSTRACT It wasn’t long after the Chicago Opera Company postponed staging The Love for Three Oranges in December of 1919 that Prokofiev decided to create The Fiery Angel. In November of the same year he was reading Valery Bryusov’s novel, “The Fiery Angel.” At the same time he was establishing a closer relationship with his future wife, Lina Codina. For various reasons the composition of The Fiery Angel endured over many years. In April of 1920 at the Metropolitan Opera, none of his three operas - The Gambler, The Love for Three Oranges, and The Fiery Angel - were accepted for staging. He received no additional support from his colleagues Sergi Diaghilev, Igor Stravinsky, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Pierre Souvchinsky, who did not care for the subject of Bryusov’s plot. Despite his unsuccessful attempts to have the work premiered, he continued working and moved from the U.S. to Europe, where he continued to compose, finishing the first edition of The Fiery Angel. He married Lina Codina in 1923. Several years later, while posing for portrait artist Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva, the composer learned about the mysteries of a love triangle between Bryusov, Andrey Bely and Nina Petrovskaya. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0127 Notes

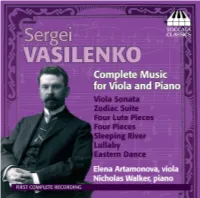

SERGEI VASILENKO AND THE VIOLA by Elena Artamonova The viola is occasionally referred to as ‘the Cinderella of instruments’ – and, indeed, it used to take a fairy godmother of a player to allow this particular Cinderella to go to the ball; the example usually cited in the liberation of the viola in a solo role is the British violist Lionel Tertis. Another musician to pay the instrument a similar honour – as a composer rather than a player – was the Russian Sergei Vasilenko (1872–1956), all of whose known compositions for viola, published and unpublished, are to be heard on this CD, the fruit of my investigations in libraries and archives in Moscow and London. None is well known; some are not even included in any of the published catalogues of Vasilenko’s music. Only the Sonata was recorded previously, first in the 1960s by Georgy Bezrukov, viola, and Anatoly Spivak, piano,1 and again in 2007 by Igor Fedotov, viola, and Leonid Vechkhayzer, piano;2 the other compositions receive their first recordings here. Sergei Nikiforovich Vasilenko had a long and distinguished career as composer, conductor and pedagogue in the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in Moscow on 30 March 1872 into an aristocratic family, whose inner circle of friends consisted of the leading writers and artists of the time, but his interest in music was rather capricious in his early childhood: he started to play piano from the age of six only to give it up a year later, although he eventually resumed his lessons. In his mid-teens, after two years of tuition on the clarinet, he likewise gave it up in favour of the oboe. -

Bitstream 46447.Pdf

I/2021 Музичка критика у Русији и Источној Европи У знак сећања на Стјуарта Кембела (1949–2018) Music Criticism in Russia and Eastern Europe In memoriam Stuart Campbell (1949–2018) Гост уредник Ивана Медић Guest Editor Ivana Medić Музикологија Часопис Музиколошког института САНУ Musicology Jоurnal of the Institute of Musicology SASA ~ 30 (I/2021) ~ ГЛАВНИ И ОДГОВОРНИ УРЕДНИК / EDITOR-IN-CHIЕF Александар Васић / Aleksandar Vasić РЕДАКЦИЈА / ЕDITORIAL BOARD Ивана Весић, Јелена Јовановић, Данка Лајић Михајловић, Ивана Медић, Биљана Милановић, Весна Пено, Катарина Томашевић / Ivana Vesić, Jelena Jovanović, Danka Lajić Mihajlović, Ivana Medić, Biljana Milanović, Vesna Peno, Katarina Tomašević СЕКРЕТАР РЕДАКЦИЈЕ / ЕDITORIAL ASSISTANT Милош Браловић / Miloš Bralović МЕЂУНАРОДНИ УРЕЂИВАЧКИ САВЕТ / INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL COUNCIL Светислав Божић (САНУ), Џим Семсон (Лондон), Алберт ван дер Схоут (Амстердам), Јармила Габријелова (Праг), Разија Султанова (Лондон), Денис Колинс (Квинсленд), Сванибор Петан (Љубљана), Здравко Блажековић (Њујорк), Дејв Вилсон (Велингтон), Данијела Ш. Берд (Кардиф) / Svetislav Božić (SASA), Jim Samson (London), Albert van der Schoot (Amsterdam), Jarmila Gabrijelova (Prague), Razia Sultanova (Cambridge), Denis Collins (Queensland), Svanibor Pettan (Ljubljana), Zdravko Blažeković (New York), Dave Wilson (Wellington), Danijela S. Beard (Cardiff) Музикологија је рецензирани научни часопис у издању Музиколошког института САНУ. Посвећен је проучавању музике као естетског, културног, историјског и друштвеног феномена и примарно усмерен на музиколошка и етномузиколошка истраживања. Редакција такође прихвата интердисциплинарне радове у чијем је фокусу музика. Часопис излази два пута годишње. Упутства за ауторе се могу преузети овде: https://music.sanu.ac.rs/en/instructions-for-authors/ Musicology is a peer-reviewed journal published by the Institute of Musicology SASA (Belgrade). It is dedicated to the research of music as an aesthetical, cultural, historical and social phenomenon and primarily focused on musicological and ethnomusicological research. -

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected]

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected] List of Addendums First Addendum – Middle Ages Second Addendum – Modern and Modern Sub-Categories A. 20th Century B. 21st Century C. Modern and High Modern D. Postmodern and Contemporary E. Descrtiption of Categories (alphabetic) and Important Composers Third Addendum – Composers Fourth Addendum – Musical Terms and Concepts 1 First Addendum – Middle Ages A. The Early Medieval Music (500-1150). i. Early chant traditions Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian Church. The simplest, syllabic chants, in which each syllable is set to one note, were probably intended to be sung by the choir or congregation, while the more florid, melismatic examples (which have many notes to each syllable) were probably performed by soloists. Plainchant melodies (which are sometimes referred to as a “drown,” are characterized by the following: A monophonic texture; For ease of singing, relatively conjunct melodic contour (meaning no large intervals between one note and the next) and a restricted range (no notes too high or too low); and Rhythms based strictly on the articulation of the word being sung (meaning no steady dancelike beats). Chant developed separately in several European centers, the most important being Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan and Ireland. Chant was developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating Mass. Each area developed its own chant and rules for celebration. In Spain and Portugal, Mozarabic chant was used, showing the influence of North Afgican music. The Mozarabic liturgy survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy. -

The Performing Style of Alexander Scriabin

Performance Practice Review Volume 18 | Number 1 Article 4 "The eP rforming Style of Alexander Scriabin" by Anatole Leikin Lincoln M. Ballard Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Ballard, Lincoln M. (2013) ""The eP rforming Style of Alexander Scriabin" by Anatole Leikin," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 18: No. 1, Article 4. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.201318.01.04 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol18/iss1/4 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book review: Leikin, Anatole. The Performing Style of Alexander Scriabin. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011. ISBN 978-0-7546-6021-7. Lincoln M. Ballard Nearly a century after the death of Russian pianist-composer Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915), his music remains as enigmatic as it was during his lifetime. His output is dominated by solo piano music that surpasses most amateurs’ capabilities, yet even among concert artists his works languish on the fringes of the standard repertory. Since the 1980s, Scriabin has enjoyed renewed attention from scholars who have contributed two types of studies aside from examinations of his cultural context: theoretical analyses and performance guides. The former group considers Scriabin as an innovative harmoni- cist who paralleled the Second Viennese School’s development of post-tonal procedures, while the latter elucidates the interpretive and technical demands required to deliver compelling performances of his music.