The Musical Partnership of Sergei Prokofiev And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club Since you’re reading this booklet, you’re obviously someone who likes to explore music more widely than the mainstream offerings of most other labels allow. Toccata Classics was set up explicitly to release recordings of music – from the Renaissance to the present day – that the microphones have been ignoring. How often have you heard a piece of music you didn’t know and wondered why it hadn’t been recorded before? Well, Toccata Classics aims to bring this kind of neglected treasure to the public waiting for the chance to hear it – from the major musical centres and from less-well-known cultures in northern and eastern Europe, from all the Americas, and from further afield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, Toccata Classics is exploring it. To link label and listener directly we run the Toccata Discovery Club, which brings its members substantial discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings, whether CDs or downloads, and also on the range of pioneering books on music published by its sister company, Toccata Press. A modest annual membership fee brings you, free on joining, two CDs, a Toccata Press book or a number of album downloads (so you are saving from the start) and opens up the entire Toccata Classics catalogue to you, both new recordings and existing releases as CDs or downloads, as you prefer. Frequent special offers bring further discounts. If you are interested in joining, please visit the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com and click on the ‘Discovery Club’ tab for more details. -

The Synthesis of Jazz and Classical Styles in Three Piano Works of Nikolai Kapustin

THE SYNTHESIS OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL STYLES IN THREE PIANO WORKS OF NIKOLAI KAPUSTIN __________________________________________________ A monograph Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board __________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS __________________________________________________________ by Tatiana Abramova August 2014 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Charles Abramovic, Advisory Chair, Professor of Piano Harvey Wedeen, Professor of Piano Dr. Cynthia Folio, Professor of Music Studies Richard Oatts, External Member, Professor, Artistic Director of Jazz Studies ABSTRACT The Synthesis of Jazz and Classical Styles in Three Piano Works of Nikolai Kapustin Tatiana Abramova Doctor of Musical Arts Temple University, 2014 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Dr. Charles Abramovic The music of the Russian-Ukrainian composer Nikolai Kapustin is a fascinating synthesis of jazz and classical idioms. Kapustin has explored many existing traditional classical forms in conjunction with jazz. Among his works are: 20 piano sonatas, Suite in the Old Style, Op.28, preludes, etudes, variations, and six piano concerti. The most significant work in this regard is a cycle of 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 82, which was completed in 1997. He has also written numerous works for different instrumental ensembles and for orchestra. Well-known artists, such as Steven Osborn and Marc-Andre Hamelin have made a great contribution by recording Kapustin's music with Hyperion, one of the major recording companies. Being a brilliant pianist himself, Nikolai Kapustin has also released numerous recordings of his own music. Nikolai Kapustin was born in 1937 in Ukraine. He started his musical career as a classical pianist. In 1961 he graduated from the Moscow Conservatory, studying with the legendary pedagogue, Professor of Moscow Conservatory Alexander Goldenweiser, one of the greatest founders of the Russian piano school. -

Aram Khachaturian

Boris Berezovsky ARAM KHACHATURIAN Boris Berezovsky has established a great reputation, both as the most powerful of Violin Sonata and Dances from Gayaneh & Spartacus virtuoso pianists and as a musician gifted with a unique insight and a great sensitivity. Born in Moscow, Boris Berezovsky studied at the Moscow Conservatory with Eliso Hideko Udagawa violin Virsaladze and privately with Alexander Satz. Subsequent to his London début at the Wigmore Hall in 1988, The Times described him as "an artist of exceptional promise, a player of dazzling virtuosity and formidable power". Two years later he won the Gold Boris Berezovsky piano Medal at the 1990 International Tchaïkovsky Competition in Moscow. Boris Berezovsky is regularly invited by the most prominent orchestras including the Philharmonia of London/Leonard Slatkin, the New York Philharmonic/Kurt Mazur, the Munich Philharmonic, Oslo Philharmonic, the Danish National Radio Symphony/Leif Segerstam, the Frankfurt Radio Symphony/Dmitri Kitaenko, the Birmingham Sympho- ny, the Berlin Symphonic Orchestra/ Marek Janowski, the Rotterdam Philharmonic, the Orchestre National de France. His partners in Chamber Music include Brigitte Engerer, Vadim Repin, Dmitri Makhtin, and Alexander Kniazev. Boris Berezovsky is often invited to the most prestigious international recitals series: The Berlin Philharmonic Piano serie, Concertgebouw International piano serie and the Royal Festival Hall Internatinal Piano series in London and to the great stages as the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris, the Palace of fine Arts in Brussells, the Konzerthaus of Vienna, the Megaron in Athena. 12 NI 6269 NI 6269 1 Her recent CD with the Philharmonia Orchestra was released by Signum Records in 2010 to coincide with her recital in Cadogan Hall. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

There's Even More to Explore!

Background artwork: SPECIAL COLLECTIONS UCHICAGO LIBRARY Kaplan and Fridkin, Agit No. 2 MUSIC THEATER ART MUSIC THEATER LECTURE / CLASS MUSIC MUSIC MUSIC / FILM LECTURE / CLASS MUSIC University of Chicago Presents University Theater/Theater and Performance Studies The University of Chicago Library Symphony Center Presents Goodman Theatre University of Chicago Presents Roosevelt University Rockefeller Chapel University of Chicago Presents TOKYO STRING QUARTET THEATER 24 PLAY SERIES: GULAG ART Orchestra Series CHEKHOv’S THE SEAGULL LECTURE / DEmoNSTRATioN PAciFicA QUARTET: 19TH ANNUAL SILENT FiLM LECTURE / DEmoNSTRATioN BY MARiiNskY ORCHESTRA FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 A CLOUD WITH TROUSERS THROUGH DECEMBER 2010 OCTOber 16 – NOVEMBER 14, 2010 BY PACIFICA QUARTET SHOSTAKOVICH CYCLE WITH ORGAN AccomPANimENT: MAsumi RosTAD, VioLA, AND (FORMERLY KIROV ORCHESTRA) Mandel Hall, 1131 East 57th Street SATURDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2010, 8 PM The Joseph Regenstein Library, 170 North Dearborn Street SATURDAY, OCTOBER 16, 2 PM SUNDAY OCTOBER 17, 2010, 2 AND 7 PM AELITA: QUEEN OF MARS AMY BRIGGS, PIANO th nd chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 First Floor Theater, Reynolds Club, 1100 East 57 Street, 2 Floor Reading Room Valery Gergiev, conductor Goodmantheatre.org, 312.443.3800 Fulton Recital Hall, 1010 East 59th Street SUNDAY OCTOBER 31, 2010, 2 AND 7 PM Jay Warren, organ SATURDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2 PM 5706 South University Avenue Lib.uchicago.edu Denis Matsuev, piano Chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2010, 8 PM Fulton Recital Hall, 1010 East 59th Street Mozart: Quartet in C Major, K. 575 As imperialist Russia was falling apart, playwright Anton SUNDAY JANUARY 30, 2011, 2 AND 7 PM ut.uchicago.edu TUESDAY, OCTOBER 12, 2010, 8 PM Rockefeller Chapel, 5850 South Woodlawn Avenue Chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 Lera Auerbach: Quartet No. -

95.3 Fm 95.3 Fm

October/NovemberMarch/April 2013 2017 VolumeVolume 41, 46, No. No. 3 1 !"#$%&'95.3 FM Brahms: String Sextet No. 2 in G, Op. 36; Marlboro Ensemble Saeverud: Symphony No. 9, Op. 45; Dreier, Royal Philharmonic WHRB Orchestra (Norwegian Composers) Mozart: Clarinet Quintet in A, K. 581; Klöcker, Leopold Quartet 95.3 FM Gombert: Missa Tempore paschali; Brown, Henry’s Eight Nielsen: Serenata in vano for Clarinet,Bassoon,Horn, Cello, and October-November, 2017 Double Bass; Brynildsen, Hannevold, Olsen, Guenther, Eide Pokorny: Concerto for Two Horns, Strings, and Two Flutes in F; Baumann, Kohler, Schröder, Concerto Amsterdam (Acanta) Barrios-Mangoré: Cueca, Aire de Zamba, Aconquija, Maxixa, Sunday, October 1 for Guitar; Williams (Columbia LP) 7:00 am BLUES HANGOVER Liszt: Grande Fantaisie symphonique on Themes from 11:00 am MEMORIAL CHURCH SERVICE Berlioz’s Lélio, for Piano and Orchestra, S. 120; Howard, Preacher: Professor Jonathan L. Walton, Plummer Professor Rickenbacher, Budapest Symphony Orchestra (Hyperion) of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in The Memorial 6:00 pm MUSIC OF THE SOVIET UNION Church,. Music includes Kodály’s Missa brevis and Mozart’s The Eve of the Revolution. Ave verum corpus, K. 618. Scriabin: Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” and Sonata No. 9, 12:30 pm AS WE KNOW IT Op. 68, “Black Mass”; Hamelin (Hyperion) 1:00 pm CRIMSON SPORTSTALK Glazounov: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B, Op. 100; Ponti, Landau, 2:00 pm SUNDAY SERENADE Westphalian Orchestra of Recklinghausen (Turnabout LP) 6:00 pm HISTORIC PERFORMANCES Rachmaninoff: Vespers, Op. 37; Roudenko, Russian Chamber Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No. 2 in g, Op. -

Read Book Sergei Prokofiev Peter and Wolf Pdf Free Download

SERGEI PROKOFIEV PETER AND WOLF PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sergei Prokofiev | 40 pages | 14 Sep 2004 | Random House USA Inc | 9780375824302 | English | New York, United States Sergei Prokofiev Peter and Wolf PDF Book Prokofiev had been considering making an opera out of Leo Tolstoy 's epic novel War and Peace , when news of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June made the subject seem all the more timely. This article contains a list of works that does not follow the Manual of Style for lists of works often, though not always, due to being in reverse-chronological order and may need cleanup. William F. You have entered an incorrect email address! The cat quickly climbs into the tree with the bird, but the duck, who has jumped out of the pond, is chased, overtaken, and swallowed by the wolf. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. To this day, elementary school children hear Peter and the Wolf during school assemblies or at concerts for young people. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. The Independent. However, Prokofiev was dissatisfied with the rhyming text produced by Antonina Sakonskaya, a then popular children's author. The Lives of Ingolf Dahl. Russian composer — Explore more from this episode More. Each character of this tale is represented by a corresponding instrument in the orchestra: the bird by a flute, the duck by an oboe, the cat by a clarinet playing staccato in a low register, the grandfather by a bassoon, the wolf by three horns, Peter by the string quartet, the shooting of the hunters by the kettle drums and bass drum. -

The Story of Peter and the Wolf

The Story of Peter and the Wolf Early one morning, Peter opened the gate and walked out into the big green meadow. On a branch of a big tree sat a little bird, Peter's friend. "All is quiet" chirped the bird happily. Just then a duck came waddling round. She was glad that Peter had not closed the gate and decided to take a nice swim in the deep pond in the meadow. Seeing the duck, the little bird flew down upon on the grass, settled next to her and shrugged his shoulders. "What kind of bird are you if you can't fly?" said he. To this the duck replied "What kind of bird are you if you can't swim?" and dived into the pond. They argued and argued, the duck swimming in the pond and the little bird hopping along Just then grandfather came out. He was upset the shore. because Peter had gone in the meadow. Suddenly, something caught Peter's attention. "It's a dangerous place. If a wolf should come He noticed a cat crawling through the grass. out of the forest, The cat thought; then what would "That little bird is you do?" busy arguing, I'll But Peter paid just grab him. no attention to Stealthily, the cat his grandfather's crept towards him on words. Boys like her velvet paws. him are not "Look out!" shouted Peter and the bird afraid of wolves. immediately flew up into the tree, while the But grandfather duck quacked angrily at the cat, from the took Peter by middle of the pond. -

Critical Success Factors in Cello Training a Comparative Study

Critical success factors in cello training a comparative study by Anzél Gerber Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PhD Music (Performance Practice) in the Department of Music Goldsmiths College, University of London Supervisor Professor Alexander Ivashkin 2008 (ii) DECLARATION I, Anzél Gerber, the undersigned, hereby declare that this dissertation, submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree PhD Music (Performance Practice), is my own original work. Signed: _______________________ Anzél Gerber (iii) ABSTRACT The research focused on the identification and ranking of critical success factors that contribute most significantly towards the training of a cello student. The empirical study was based on a sample of cello teachers in four countries selected for the study, namely Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. A literature study, identifying a broad category of factors that could contribute towards successful cello training, formed the basis of the questionnaire. These critical success factors included the quality of the teacher, acquired skills, the talent and giftedness of the student, support rendered to the student, and the curriculum. Each of these factors comprised five sub factors. The respondents were required to rank these factors in order of importance. In the final analysis, they were requested to rank the five main factors. A statistical process of ranking (forced ranking) and Kruskal-Wallis was applied to rank and analyse the responses of the cello teachers in the survey. The critical success factors that contribute the most significantly towards successful cello training were identified and compared. ________________________________ (iv) PREFACE This study is in partial fulfilment for the degree PhD Music Performance at Goldsmiths College, University of London. -

Vi Saint Petersburg International New Music Festival Artistic Director: Mehdi Hosseini

VI SAINT PETERSBURG INTERNATIONAL NEW MUSIC FESTIVAL ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: MEHDI HOSSEINI 21 — 25 MAY, 2019 facebook.com/remusik.org vk.com/remusikorg youtube.com/user/remusikorg twitter.com/remusikorg instagram.com/remusik_org SPONSORS & PARTNERS GENERAL PARTNERS 2019 INTERSECTIO A POIN OF POIN A The Organizing Committee would like to express its thanks and appreciation for the support and assistance provided by the following people: Eltje Aderhold, Karina Abramyan, Anna Arutyunova, Vladimir Begletsov, Alexander Beglov, Sylvie Bermann, Natalia Braginskaya, Denis Bystrov, Olga Chukova, Evgeniya Diamantidi, Valery Fokin, Valery Gergiev, Regina Glazunova, Andri Hardmeier, Alain Helou, Svetlana Ibatullina, Maria Karmanovskaya, Natalia Kopich, Roger Kull, Serguei Loukine, Anastasia Makarenko, Alice Meves, Jan Mierzwa, Tatiana Orlova, Ekaterina Puzankova, Yves Rossier, Tobias Roth Fhal, Olga Shevchuk, Yulia Starovoitova, Konstantin Sukhenko, Anton Tanonov, Hans Timbremont, Lyudmila Titova, Alexei Vasiliev, Alexander Voronko, Eva Zulkovska. 1 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall 4 Masterskaya M. K. Anikushina FESTIVAL CALENDAR Dekabristov St., 37 Vyazemsky Ln., 8 mariinsky.ru vk.com/sculptorstudio 2 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre 5 “Lumiere Hall” creative space TUESDAY / 21.05 19:00 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall Fontanka River Embankment 49, Lit A Obvodnogo Kanala emb., 74А ensemble für neue musik zürich (Switzerland) alexandrinsky.ru lumierehall.ru 3 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov 6 The Concert Hall “Jaani Kirik” Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Dekabristov St., 54A Glinka St., 2, Lit A jaanikirik.ru WEDNESDAY / 22.05 13:30 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov conservatory.ru Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Composer meet-and-greet: Katharina Rosenberger (Switzerland) 16:00 Lumiere Hall Marcus Weiss, Saxophone (Switzerland) Ensemble for New Music Tallinn (Estonia) 20:00 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre Around the Corner (Spain, Switzerland) 4 Vyazemsky Ln. -

MUSICAL CENSORSHIP and REPRESSION in the UNION of SOVIET COMPOSERS: KHRENNIKOV PERIOD Zehra Ezgi KARA1, Jülide GÜNDÜZ

SAYI 17 BAHAR 2018 MUSICAL CENSORSHIP AND REPRESSION IN THE UNION OF SOVIET COMPOSERS: KHRENNIKOV PERIOD Zehra Ezgi KARA1, Jülide GÜNDÜZ Abstract In the beginning of 1930s, institutions like Association for Contemporary Music and the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians were closed down with the aim of gathering every study of music under one center, and under the control of the Communist Party. As a result, all the studies were realized within the two organizations of the Composers’ Union in Moscow and Leningrad in 1932, which later merged to form the Union of Soviet Composers in 1948. In 1948, composer Tikhon Khrennikov (1913-2007) was appointed as the frst president of the Union of Soviet Composers by Andrei Zhdanov and continued this post until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Being one of the most controversial fgures in the history of Soviet music, Khrennikov became the third authority after Stalin and Zhdanov in deciding whether a composer or an artwork should be censored or supported by the state. Khrennikov’s main job was to ensure the application of socialist realism, the only accepted doctrine by the state, on the feld of music, and to eliminate all composers and works that fell out of this context. According to the doctrine of socialist realism, music should formalize the Soviet nationalist values and serve the ideals of the Communist Party. Soviet composers should write works with folk music elements which would easily be appreciated by the public, prefer classical orchestration, and avoid atonality, complex rhythmic and harmonic structures. In this period, composers, performers or works that lacked socialist realist values were regarded as formalist. -

Program Notes by Dr

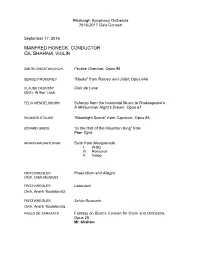

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits.