The Impact of Ancient Tree Form on Modern Landscape Preferences T ⁎ Joseph B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masondentinger Umn 0130E 1

The Nature of Defense: Coevolutionary Studies, Ecological Interaction, and the Evolution of 'Natural Insecticides,' 1959-1983 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Rachel Natalie Mason Dentinger IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Mark Borrello December 2009 © Rachel Natalie Mason Dentinger 2009 Acknowledgements My first thanks must go to my advisor, Mark Borrello. Mark was hired during my first year of graduate school, and it has been my pleasure and privilege to be his first graduate student. He long granted me a measure of credit and respect that has helped me to develop confidence in myself as a scholar, while, at the same time, providing incisive criticism and invaluable suggestions that improved the quality of my work and helped me to greatly expand its scope. My committee members, Sally Gregory Kohlstedt, Susan Jones, Ken Waters, and George Weiblen all provided valuable insights into my dissertation, which will help me to further develop my own work in the future. Susan has given me useful advice on teaching and grant applications at pivotal points in my graduate career. Sally served as my advisor when I first entered graduate school and has continued as my mentor, reading nearly as much of my work as my own advisor. She never fails to be responsive, thoughtful, and generous with her attention and assistance. My fellow graduate students at Minnesota, both past and present, have been a huge source of encouragement, academic support, and fun. Even after I moved away from Minneapolis, I continued to feel a part of this lively and cohesive group of colleagues. -

Behavioral Flexibility in Primates: Causes and Consequences DEVELOPMENTS in PRIMATOLOGY: PROGRESS and PROSPECTS

Behavioral Flexibility in Primates: Causes and Consequences DEVELOPMENTS IN PRIMATOLOGY: PROGRESS AND PROSPECTS Series Editor: Russell H. Tuttle University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois This peer-reviewed book series will meld the facts of organic diversity with the continuity of the evolutionary process. The volumes in this series will exemplify the diversity of theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches currently employed by primatologists and physical anthropologists. Specific coverage includes: primate behavior in natural habitats and captive settings; primate ecology and conservation; functional morphology and developmental biology of primates; primate systematics; genetic and phenotypic differences among living primates; and paleoprimatology. ALL APES GREAT AND SMALL VOLUME I: AFRICAN APES Edited by Biruté M.F. Galdikas, Nancy Erickson Briggs, Lori K. Sheeran, Gary L. Shapiro and Jane Goodall THE GUENONS: DIVERSITY AND ADAPTATION IN AFRICAN MONKEYS Edited by Mary E. Glenn and Marina Cords ANIMAL MINDS, HUMAN BODIES By W.A. Hillix and Duane Rumbaugh COMPARATIVE VERTEBRATE COGNITION Edited by Lesley J. Rogers and Gisela Kaplan ANTHROPOID ORIGINS: NEW VISIONS Edited by Callum F. Ross and Richard F. Kay MODERN MORPHOMETRICS IN PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY Edited by Dennis E. Slice BEHAVIORAL FLEXIBILITY IN PRIMATES: CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES By Clara B. Jones Behavioral Flexibility in Primates: Causes and Consequences CLARA B. JONES Fayetteville State University Fayetteville, North Carolina Theoretical Primatology Project Fayetteville, North Carolina Community Conservation, Inc. Gays Mills, Wisconsin Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jones, Clara B. Behavioral flexibility in primates : causes and consequences / Clara B. Jones. p. cm.—(Developments in primatology) Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-387-23297-4 1. Primates—Behavior. -

Nhbs Monthly Catalogue New and Forthcoming Titles Issue: 2013/01 January 2013 [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913

nhbs monthly catalogue new and forthcoming titles Issue: 2013/01 January 2013 www.nhbs.com [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913 Welcome to the January 2013 edition of the NHBS Monthly Catalogue. This monthly Zoology: update contains all of the wildlife, science and environment titles added to nhbs.com in Mammals the last month. Birds Editor's Picks - New in Stock this Month Reptiles & Amphibians Fishes ● Africa: Eye to Eye with the Unknown Invertebrates ● The Aloe of Madagascar / Les Aloe de Madagascar Palaeontology ● Guide to the UK Cetaceans and Seals Marine & Freshwater Biology ● Guides sur la Diversite Biologique de Madagascar General Natural History ● Illustrated Guide to Home Biology Experiments Regional & Travel ● The Natural History of Canadian Mammals ● The Natural History of the Crustacea Vol 1: Functional Morphology and Diversity Botany & Plant Science ● Natural History of Rangitoto Island Animal & General Biology ● Mammals of South Asia, Volume 1 Evolutionary Biology ● Moa: The Life and Death of New Zealand's Legendary Bird Ecology ● The R Book (2nd Edition) Habitats & Ecosystems ● RES Handbook, Volume 5, Part 17d: True Weevils (Part III) Conservation & Biodiversity ● Vegetation Ecology ● Walking Sideways: The Remarkable World of Crabs Environmental Science ● The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies? Physical Sciences Sustainable Development Data Analysis Find out more about services for libraries and organisations: NHBS LibraryPro Reference Best wishes, -The NHBS Team View this Monthly Catalogue as a web page or save/print it as a .pdf document. Mammals A Guide to the Mammals of China (Pocket Edition) 432 pages | 384 colour illustrations, 558 Andrew T Smith, Yan Xie and Federico Gemma maps | China's breathtaking diversity of natural habitats – from mountains and deserts to grasslands Paperback | NYP 05/2013 | and lush tropical forests – is home to more than 10 per cent of the world's mammal species. -

I Rtin Itf Sidoiimtiipj Mm Ix% M

C%H I rtin itf SiDoiiMtiipj mm iX% m DIV. 10 AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 2 (1) Involution. Creativity, and Aesthetics (.«re*jor\ I, Feist, Guest Fditor Ernst Haeckel - Kunstformen der Natur. Tafel 74: Cypnpedium (Orchideac. Venusblumen), 1904 Sir Edward Povnter - A Comer of the Villa Emile Mimicr - llcr '.'nai dian ain'cl km Sir l.iiwrcinc Mniu-Tadema f a I iii ihl\ Paradise William Alolplw Bouguereau - L'Anwur an papillon William Adolphv Bougneremt Le Coquillage Bulletin of Psychology and the Arts Vol 2 (1) Contents Evolution, Creativity, and Aesthetics - Gregory J. Feist, Guest Editor 33 Creativity as a Secondary Darwinian Process 2 Three Perspectives on Evolution, Creativity, and Aesthetics Dean Keith Simonton Gregory J. Feist 39 The Role of Creativity in the Dialectical Evolution of Ideas 3 An Evolutionary Perspective on the Nature of Art Robert J. Sternberg Nancy E. Aiken 7 Ars Brevis, Vita Longa: The Possible Evolutionary Antecedents of 44 Division 10 News Art and Aesthetics Message from the President John L. Bradshaw Sandra W. Russ 11 Natural and Sexual Selection in the Evolution of Creativity Message from the Past President Gregory J. Feist Robert J. Sternberg 16 Fit To Be Eyed: Genes, Culture and Creative Minds Charles J. Lumsden Editorial 20 Aesthetic Fitness: How Sexual Selection shaped Artistic Virtuosity Colin Martindale as a Fitness Indicator and Aesthetic Preferences as Mate Choice Criteria Div. 10 Executive Committee endorses Bob Sternberg for Goeffrey F. Miller APA President 25 An Evolutionary Perspective on Aesthetics Announcements Gordon H. Orians 30 Creativity in Art: Stylistic Waves and Monotonic Evolutionary Division 10 2001 APA Program Trends (Information Approach) Vladimir M. -

Views Expressed Are Those of the Publication Date of the Issue

Dædalus coming up in Dædalus: Dædalus on capitalism Joyce Appleby, John C. Bogle, Lucian Bebchuk, Robert W. Fogel, & democracy Jerry Z. Muller, Richard Epstein, Benjamin M. Friedman, John Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Dunn, Robin Blackburn, and Gerhard Loewenberg Spring 2007 on the public interest William Galston, E. J. Dionne, Jr., Seyla Benhabib, Jagdish Bhagwati, Adam Wolfson, Lance Taylor, Gary Hart, Nathan Glazer, Robert N. Bellah, Nancy Rosenblum, Amy Gutmann, and Christine Todd Spring 2007: on sex Whitman comment Paul Ehrlich & Marcus W. Feldman The fallacy of genetic reductionism 5 on life Anthony Kenny, Thomas Laqueur, Shai Lavi, Lorraine Daston, Paul Rabinow, Robert P. George, Robert J. Richards, Nikolas Rose, John on Tim Birkhead Promiscuity 13 sex Broome, Jeff McMahan, and Adrian Woolfson Joan Roughgarden Challenging Darwin 23 Brian Charlesworth Why bother? The evolutionary function of sex 37 on nature Leo Marx, William Cronon, Cass Sunstein, Daniel Kevles, Bill McKibben, Harriet Ritvo, Gordon Orians, Camille Parmesan, Anne Fausto-Sterling Frameworks of desire 47 Margaret Schabas, and Philip Tetlock & Michael Oppenheimer Elizabeth Benedict On the Internet 58 Wendy Doniger In the Kamasutra 66 on cosmopolitanism Martha C. Nussbaum, Stanley Hoffmann, Margaret C. Jacob, A. A. Stanley Corngold Franz Kafka & sex 79 Long, Pheng Cheah, Darrin McMahon, Helena Rosenblatt, Samuel Terry Castle The lesbianism of Philip Larkin 88 Scheffler, Arjun Appadurai, Rogers Smith, Peter Brooks, and Craig Lawrence Cohen Homosexuality & hope in India 103 Calhoun annals Greil Marcus A trip to Hibbing High 116 plus poetry by Lawrence Dugan, Molly McQuade, Ted Richer, C. D. Wright &c.; ½ction by Chris Abani, Nadine Gordimer &c.; and poetry Charles Simic Darkened Chessboard & Secret History 125 notes by Keith T. -

Habitat Selection Theory and the Preference for Flowers – Is There Empirical Support?

Habitat Selection Theory and the Preference for Flowers – Is There Empirical Support? Martin Hůla and Jaroslav Flegr Charles University, Faculty of Science, Prague, Czech Republic. Corresponding author: Martin Hůla ([email protected]), Viničná 7, Prague 2, 128 00, CZ Abstract Although the aesthetic appreciation of flowers is a well-known aspect of human behavior, theories explaining its origin are missing. An exception is the evolutionary theory of Heerwagen and Orians, who suggest that humans emotionally respond to flowers because they signal food availability. However, fruits are stronger and more direct signals of food availability than flowers, therefore fruits should elicit stronger emotional responses than flowers. To test the theory, we performed two online studies in Czechia. The participants (n = 3354 and 744 respectively) indicated on a six-point scale their preferences for the photographs of 14 edible Czech plant species (study A) and 20 edible plant species from African savannas (study B), varying in their growth stage (flowering, fruiting). Paired t- tests found no preference for Czech fruiting plants and a strong preference for African flowering plants (p<0.0001, Cohen’s d = 1.24). Our results show that the theory deserves renewed attention. Keywords evolutionary aesthetics, habitat selection, flower preference, evolutionary anthropology 1. Background Human attraction towards flowers is a phenomenon that is manifested in various ways, from ornamental gardens and flower exhibits to product design and get-well gifts. The volume of the global cut flower trade reaches € 15 billion per year (Mamias, 2018). One can find abundant examples of the aesthetic responses to flowers in many different cultures and historical periods. -

FOREIGN RIGHTS EDITION Spring 2014 Guide to Subjects

The University of Chicago Press 1427 East 60th Street Chicago, IL 60637 CHICAGO SPRING BOOKS 2014 FOREIGN RIGHTS EDITION Spring 2014 Guide to Subjects African American Judaica 47, 49 Studies 33, 44–45, 68 Law 27, 44, 38 African Studies 52-53 Linguistics 55 American History 8, 23, 26, 44–46, 64, 69, 71, 73, Literary Criticism 50, 76 65, 70, 74 Anthropology 20, 41, Literature 12, 62 52–53, 55–56, 67 Medicine 48, 76 Archaeology 70 Music 3, 41, 69, 71 Architecture 65 Nature 4, 7, 9, 15 Art 2, 21-22, 34, 43 Pets 58 Biography 6, 63, 65 Philosophy 16, 28, 33, Business 31 35, 49, 50–52, 54, 66, 71, 73–74 Classics 49, 66, 68, 70 Photography 8 Cultural Studies 42, 64 Poetry 18 Current Events 1, 6, 13 Political Science 27–30, Economics 1, 39, 72 32–34, 47, 51, 71, 75 Education 10, 36–39, 61 Reference 10–11 European History 25, 48 Religion 35, 53, 67, 72 Film Studies 21, 43 Science 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 20, 22–26, 40, 48, 68, 73–75 Gardening 15 Sociology 13, 32, 40, 42 Gay and Lesbian Stud- ies 19, 33–34 Sports 14 Graphic Novels 2 Travel 3, 59 History 17, 24, 26, 32, Women’s Studies 19, 43, 35, 42, 44, 46–49, 59–60, 56 67–68, 70, 72, 75-76 Cover and catalog design by Mary Shanahan ATIF MIAN and AMIR SUFI House of Debt How They (and You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It from Happening Again he Great American Recession resulted in the loss of eight million jobs between 2007 and 2009. -

Makkar-Ac-Reading-50-Tests-4.Pdf

1 IELTS ACADEMIC READINGS FOR KIRAN’S IELTS CENTRE Reading 1 The world is our oyster A. Independent travel is on the increase and while package holidays which offer an all inclusive price for transport, accommodation and often even food are financially attractive to many, according to tourism analyst Thomas Cooper, an increasing number of people now prefer a less-tailored holiday and the freedom to make spur of the moment decisions and changes to their intended plan. B. Internet based information sites about backpacking destinations are prolific and publications aimed at independent travellers on a budget exist for almost every destination imaginable. Some people, particularly first-time backpackers, may elect to travel with a friend or acquaintance; however, a large percentage of backpackers travel alone, assured by the knowledge that they are likely to meet, with ease, a number of like-minded individuals throughout their journey and staying in their backpacker accommodation. Alan Park, who has travelled extensively through Europe, Australasia and several other parts of the globe, says most accommodation establishments aimed at the backpacker market are designed with communal kitchens, dormitories and entertainment areas which lend themselves to allowing residents to socialize with ease and quickly breakdown barriers with strangers that may usually exist in day to day life. C. Many backpackers of European origin are attracted to the Southern Hemisphere, Australia being a major destination of choice. Cooper attributes this high level of interest to the possibilities of legal working holiday visas for many nationalities and consequent short-term work opportunities making extended travel financially feasible, in addition to the attractive climate and outback appeal. -

General Kofi A. Annan the United Nations United Nations Plaza

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS O2 1 39 October 10, 1997 HENRY W. KENDALL ROOM 2.4-51 4 (617) 253-7584 JULIUS A. STRATTON PROFESSOR OF PHYSICS Secretary- General Kofi A. Annan The United Nations United Nations Plaza . ..\ U New York City NY Dear Mr. Secretary-General: I have received your letter of October 1 , which you sent to me and my fellow Nobel laureates, inquiring whetHeTrwould, from time to time, provide advice and ideas so as to aid your organization in becoming more effective and responsive in its global tasks. I am grateful to be asked to support you and the United Nations for the contributions you can make to resolving the problems that now face the world are great ones. I would be pleased to help in whatever ways that I can. ~~ I have been involved in many of the issues that you deal with for many years, both as Chairman of the Union of Concerne., Scientists and, more recently, as an advisor to the World Bank. On several occasions I have participated in or initiated activities that brought together numbers of Nobel laureates to lend their voices in support of important international changes. -* . I include several examples of such activities: copies of documents, stemming from the . r work, that set out our views. I initiated the World Bank and the Union of Concerned Scientists' examples but responded to President Clinton's Round Table initiative. Again, my appreciation for your request;' I look forward to opportunities to contribute usefully. Sincerely yours ; Henry; W. -

Habitat Selection and the Evolutionary Aesthetics of Landscape Preference

Documenta Praehistorica XLVII (2020) Habitat selection and the evolutionary aesthetics of landscape preference Marko {koric´, Aleksej Ki[juhas Faculty of Philosophy, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, RS [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT – This paper analyses the processes of habitat selection and human landscape preferences from an evolutionary perspective, with the aim of demonstrating how humans aesthetically choose, assess and aspire to live in an environment in which our species and our ancestors evolved in dur- ing the pre-Neolithic period. We present the basics of evolutionary aesthetics, then analyse the pro- cess of habitat selection and the most influential evolutionary theories of landscape preference. Finally, we refer to applied empirical research and point out that a comprehensive evolutionary the- ory must also take into account the psychological and cultural elements that affect human well-being. KEY WORDS – evolutionary aesthetics; habitat selection; biophilia; landscape preference Izbira /ivljenjskega prostora in evolucijska estetika krajinskih preferenc IZVLE∞EK – V ≠lanku analiziramo proces izbire ∫ivljenjskega prostora in preference ljudi pri izbiri krajine iz evolucijske perspektive z namenom, da poka∫emo, kako ljudje na podlagi estetike izbira- jo, ocenjujejo in stremijo k ∫ivljenju v okolju, v katerem so se v obdobju pred neolitikom razvijali na∏a vrsta in na∏i predniki. Predstavljamo osnove evolucijske estetike, nato analiziramo proces iz- bire ∫ivljenjskega prostora in najbolj vplivne evolucijske teorije o krajinskih preferencah. Na koncu se sklicujemo na uporabne empiri≠ne raziskave in poka∫emo, da mora celovita evolucijska teorija upo∏tevati tudi psiholo∏ke in kulturne elemente, ki vplivajo na dobro po≠utje ljudi. -

Agent Orange, Antiwar Protest and Environmental Destruction in Vietnam

INVENTING ECOCIDE: AGENT ORANGE, ANTIWAR PROTEST AND ENVIRONMENTAL DESTRUCTION IN VIETNAM ____________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ____________________________________ by David Zierler August, 2008 © by David Zierler 2008 All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT INVENTING ECOCIDE: AGENT ORANGE, ANTIWAR PROTEST AND ENVIRONMENTAL DESTRUCTION IN VIETNAM David Zierler Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chairs Richard H. Immerman and Andrew C. Isenberg This project examines the scientific developments, strategic considerations, and political circumstances that led to the rise and fall of herbicidal warfare in Vietnam. The historical narrative draws on a wide range of primary and secondary source literature on the Vietnam War and the Cold War, the history of science, and American and international history of the 1960s and 1970s. The author conducted archival research in the United States in a variety government and non-government research facilities and toured formerly sprayed areas in Vietnam. The thesis explains why American scientists were able to force an end to the herbicide program in 1971 and ensure that the United States would not engage in herbicidal warfare in the future. This political success can be understood in the context of two major political transformations in the Vietnam Era: the collapse of Cold War containment as a salient model of American foreign policy, and the development of globally-oriented environmental politics and security regimes. The movement to end herbicidal warfare helped shift the meaning of security away from the Cold War toward transnational efforts to combat environmental problems that threaten all of the world’s people. -

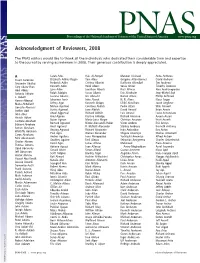

Acknowledgment of Reviewers, 2008

Proceedings of the National Academy ofPNAS Sciences of the United States of America www.pnas.org Acknowledgment of Reviewers, 2008 The PNAS editors would like to thank all the individuals who dedicated their considerable time and expertise to the journal by serving as reviewers in 2008. Their generous contribution is deeply appreciated. A Sarah Ades Qais Al-Awqati Marwan Al-shawi Anne Andrews Stuart Aaronson Elizabeth Adkins-Regan Tom Alber Gre´goire Altan-Bonnet David Andrews Alejandro Aballay Frederick Adler Cristina Alberini Karlheinz Altendorf Tim Andrews Cory Abate-Shen Kenneth Adler Heidi Albers Sonia Altizer Timothy Andrews Abul Abbas Lynn Adler Jonathan Alberts Russ Altman Alex Andrianopoulos Antonio Abbate Ralph Adolphs Susan Alberts Eric Altschuler Jean-Michel Ane´ L. Abbott Luciano Adorini Urs Albrecht Burton Altura Phillip Anfinrud Hanna Abboud Johannes Aerts John Alcock N. R. Aluru Klaus Anger Maha Abdellatif Jeffrey Agar Kenneth Aldape Lihini Aluwihare Jacob Anglister Goncalo Abecasis Munna Agarwal Courtney Aldrich Pedro Alzari Wim Annaert Steffen Abel Sunita Agarwal Jane Aldrich David Amaral Brian Annex John Aber Aneel Aggarwal Richard Aldrich Luis Amaral Lucio Annunciato Hinrich Abken Ariel Agmon Kristina Aldridge Richard Amasino Aseem Ansari Carmela Abraham Noam Agmon Maria-Luisa Alegre Christian Amatore Kristi Anseth Edward Abraham Bernard Agranoff Nicole Alessandri-Haber Victor Ambros Eric Anslyn Aneil Agrawal R. McNeill Alexander Stanley Ambrose Kenneth Anthony Soman Abraham Anurag Agrawal Richard Alexander Indu Ambudkar