Westward Expansion: a New History CHOICES for the 21St Century Education Program July 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Public Land Heritage: from the GLO to The

Our Public Land Heritage: From the GLO to the BLM Wagon train Placer mining in Colorado, 1893 Gold dredge in Alaska, 1938 The challenge of managing public lands started as soon as America established its independence and began acquiring additional lands. Initially, these public lands were used to encourage homesteading and westward migration, and the General Land Office (GLO) was created 1861 • 1865 to support this national goal. Over time, however, values and attitudes American Civil War regarding public lands shifted. Many significant laws and events led to the establishment of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and 1934 laid the foundation for its mission to sustain the health, diversity, and 1872 1894 Taylor Grazing Act productivity of America’s public lands for the use and enjoyment of General Mining Law Carey Act authorizes authorizes grazing 1917 • 1918 present and future generations. identifies mineral transfer of up to districts, grazing lands as a distinct 1 million acres of World War I regulation, and www.blm.gov/history 1824 1837 1843 1850 1860 class of public lands public desert land to 1906 1929 public rangeland subject to exploration, states for settling, improvements in Office of Indian On its 25th “Great Migration” First railroad land First Pony Express Antiquities Act Great Depression occupation, and irrigating, and western states 1783 1812 Affairs is established anniversary, the on the Oregon Trail grants are made in rider leaves 1889 preserves and 1911 purchase under cultivating purposes. Begins (excluding Alaska) General in the Department General Land Office begins. Illinois, Alabama, and St. Joseph, Missouri. Oklahoma Land Rush protects prehistoric, Weeks Act permits Revolutionary War ends stipulated conditions. -

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire Template

8th Grade U.S. History Chapter 13 Review #1 What is one reason people rushed to California in 1848? Discovery of Approval of A: B: gold/mineral slavery deposits Opening of a cross- Numerous rivers C: D: country railroad for farming B. Discovery of gold/mineral deposits #2 The concept of Manifest Destiny was important during the _______. War of 1812 A: B: Mexican War Revolutionary French and C: War D: Indian War B. Mexican War #3 “We had to search for a pass between the mountains that would allow us to get to Oregon.” This pioneer was writing about what mountain range? Rocky Appalachian A: B: C: Smoky D: Adirondack A. Rocky #4 What natural barrier would a traveler heading west to Colorado encounter? Rio Grande A: Great Lakes B: River Rocky Sierra Nevada C: Mountains D: Mountains C. Rocky Mountains #5 Manifest destiny was the idea that_____. American democracy Americans should A: should spread across B: conserve natural the continent environment More fertile land More land would C: was needed for D: increase U.S. food production international power A. American democracy should spread across the continent #6 The belief in Manifest Destiny was a MAJOR cause of ________. Conflicts Land disputes A: between farmers B: between competing & ranchers railroads Land disputes Conflicts between C: east of the D: U.S. & neighboring Appalachian Mts. countries D. Conflicts between U.S. & neighboring countries #7 “Our manifest destiny (is) to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” This statement influenced which idea? Abolition Tariff of A: B: movement Abominations Completion of Settlement of C: D: the Erie Canal Oregon country D. -

Arizona and the Gadsden Purchase

Location, Location, Location: Arizona and the Gadsden Purchase Author Keith White Grade Level High School Duration 2 class periods National Standards AZ Standards Arizona Social Science Standards GEOGRAPHY ELA Geography Element 1: The Reading The use of geographic World in Spatial Key Ideas and Details representations and tools help Terms 11-12.RI.1 Cite strong and thorough individuals understand their world. 1. How to use maps textual evidence to support analysis of HS.G1.1 Use geographic data to explain and other geographic what the text says explicitly as well as and analyze relationships between representations, inferences drawn from the text, locations of place and regions. Key tools geospatial including determining where the text and representations such as maps, technologies, and leaves matters uncertain. remotely sensed and other images, spatial thinking to Integration of Knowledge and Ideas tables, and graphs understand and 11-12.RI.7 Integrate and evaluate future conditions on Earth’s surface. communicate multiple sources of information HS.G3.1 Analyze the reciprocal nature of information presented in diverse formats and how historical events and the diffusion of Element 2: Places media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as ideas, technologies, and cultural and Regions well as in words) in order to address a practices have influenced migration 4. The physical and question or solve a problem. patterns and the distribution of human human characteristics Writing population. of places Text Types and Purposes HS.G3.5 Evaluate the impact of social, Element 4: Human 11-12.W.2 Write political, and economic decisions that Systems informative/explanatory texts, have caused conflict or promoted 12. -

Learn About the United States Quick Civics Lessons for the Naturalization Test

Learn About the United States Quick Civics Lessons for the Naturalization Test M-638 (rev. 02/19) Learn About the United States: Quick Civics Lessons Thank you for your interest in becoming a citizen of the United States of America. Your decision to apply for IMPORTANT NOTE: On the naturalization test, some U.S. citizenship is a very meaningful demonstration of answers may change because of elections or appointments. your commitment to this country. As you study for the test, make sure that you know the As you prepare for U.S. citizenship, Learn About the United most current answers to these questions. Answer these States: Quick Civics Lessons will help you study for the civics questions with the name of the official who is serving and English portions of the naturalization interview. at the time of your eligibility interview with USCIS. The USCIS Officer will not accept an incorrect answer. There are 100 civics (history and government) questions on the naturalization test. During your naturalization interview, you will be asked up to 10 questions from the list of 100 questions. You must answer correctly 6 of the 10 questions to pass the civics test. More Resources to Help You Study Applicants who are age 65 or older and have been a permanent resident for at least 20 years at the time of Visit the USCIS Citizenship Resource Center at filing the Form N-400, Application for Naturalization, uscis.gov/citizenship to find additional educational are only required to study 20 of the 100 civics test materials. Be sure to look for these helpful study questions for the naturalization test. -

1 How Did the U.S. Government Help People Traveling the Santa Fe Trail

1 2 3 4 5 How did the U.S. government How did the railroad help U.S. Donner Party Why were Mormons Advantages of the U.S. in the help people traveling the expansion? persecuted? Mexican American War. Santa Fe Trail? Headed west late in the year. Moved population west, Were trapped in snowstorm Practice of polygamy, more Better equipped Provided military help to deal allowed for shipping around and starved. than one wife with threats from Indians the country 6 7 8 9 10 Alamo Mexican Cession Bear Flag Revolt Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Santa Anna Old mission where Texas Territory gained from American settlers declared Ended war with Mexico, U.S. Leader of the Mexicans freedom fighters were Mexican War (Nevada, Utah, California an independent gained Nevada, Utah, fighting against Texas/U.S. massacred California) country, caused fight with California Mexico 11 12 13 14 15 John Tyler Brigham Young Manifest Destiny Mormon Trail Oregon Trail U.S. president, annexed Texas Head of Mormon Church, Belief that Americans would Traveled by Mormons to Utah 2000 mile trail to the Pacific moved them to Utah move West and settle the in pursuit of religious Coast entire country freedom 16 17 18 19 20 Santa Fe Trail Mormons Fur Trade Gold Rush Were 49ers successful? Trade route, protected by Moved to Utah for religious Major reason for moving Thousands moved to No, most lost money army due to attacks from freedom West California to search for gold Native Americans 21 22 23 24 25 Who benefited from the Gold How did Gold Rush impact List current states that are Gadsden Purchase List 6 flags that have flown Rush? California? part of the Mexican Cession. -

I846-I912 a Territorial History

The Far Southwest I846-I912 A Territorial History Howard Roberts Lamar The Norton Library W • W .-NORTON & COMPANY • INC· NEW YORK For Shirley Acknowledgments The number of individuals and institutions to whom I am indebted for making this study pos sible is so great that it is impossible for me to ex~ press adequate thanks to all. Among the many officials and staff members of the National ~rchives who have courteously searched COPYRIGHT@ 1970 BY W. W. NORTON & COMPANY, INC. out pertinent materials in the Territorial Papers of the United States COPYRIGHT© 1966 BY YALE UNIVERSITY I am particularly grateful to the late Clarence E. Carter and to Robert Baluner. Ray Allen Billington not only provided support First published in the Norton Library 1970 by arrangement with Yale University Press. and advice but gave me a chance to test several of my conclusions in public meetings. George W. Pierson, as chairman of the Yale History Department, arranged two leaves of absence for me between 1959 SBN 393 00522 4 and 1961, so that I could give full time to the study. Archibald Hanna, Director of the Yale Western Americana Collection, did all in his power to supply me with needed manuscript materials on the Far Southwest. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A grant from the Henry E. Huntington Library in 1957 permitted Published simultaneously in Canada by George J. McLeod Limited, Toronto-. the use of the splendid New Mexico Collection of William G. Ritch. In 1959 a fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies enabled me to visit state archives and historical libraries throughout the Southwest. -

Bulletin 74. Report on Boundaries of Territorial Acquisitions

Twelfth Census of the United States. CENSUS BULLETIN. No. 74. WASHINGTON, D. C. July 20, 1901. REPORT ON BOUNDARIES OF TERRITORIAL ACQUISITIONS .. Hon. WILLIAM R. MERRIAM, have no official standing, but are entitled only to sucl1 Director of the Census. weight as is carried by the names of the individuals Sm: I have the honor to transmit herewith, for pub signing the report. Even so, there is no doubt that its lication as a census bulletin, the "Report of a Conference results have materially decreased the conflicts of official upon the Boundaries of the Successive Acquisitions of Ter authority in this field. The main conclusions of the con._ ritory by the United States." The conference was con ference, as detailed in the following pages, may be sum stituted of representatives of the Department of State, the marized as follows : Coast and Geodetic Survey, the Geological Survey, the 1. The region between the Mississippi "River and lakes Census Office, and the Ubrary of Congress. It was ap Maurepas and Pontchartrain to the west, and the Perdido pointed at the req nest of the Census Office, and as an River to the east, should not be assigned either to the advisory committee to that office on certain controverted Louisiana Purchase or to the Florida Purchase, but subjects. marked with a legend indicating that title to it between In the '' Statistical Atlas of the United States, Based 1803 and 1819 was in dispute. upon Results of the Eleventh Census," is a map (Plate I) 2. The line between the Mississippi River and the Lake giving the boundaries of the successive acquisitions of ter of the Woods, separating the territory of the United ritory by the United States, exclusive of Alaska. -

Treaty of Hidalgo Aquistions

Treaty Of Hidalgo Aquistions Mellowing Truman never nichers so stuffily or spread-eagles any driving histrionically. Eurasian Waverly alienating her SheffyBengalese homologize so blithesomely some calcars that Lucio respectively. lease very greyly. Harnessed and obtect Fons trip her alderman incurvate while Tendency to northern and negotiations were the united states as far stronger fugitive slave state whigs treaty of hidalgo, one thousand people related to purchase doubled the rio grande as Century demonstrates that the acquisition and control of land was that primary. Transcontinental railroad track in several days, shall be done because of hidalgo, including nominating conventions on. Acquired almost opposite of that territory in the 14 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. Mexico City in September 14 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended war. The cheat of Guadalupe Hidalgo also how as the Mexican Cession. How Acquired purchased from Spain in the Adams-Onis Treaty Florida Purchase. Strength in guam are excluded by treaty of hidalgo aquistions, especially those of. Offering an appropriately large compensatory payment of hidalgo: treaty of hidalgo aquistions for mexicans were adverse to mexico city of hidalgo acquisitions are you tried to use of. Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Wikipedia. Historic Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo artifacts to be auctioned. White folks acquired land legally from many Mexicans a drill of whom. The canvas of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 14 This massive land grab was significant opportunity the moist of extending slavery into newly acquired territories had. Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo 14 Immigration History. The warrior set line border between Texas and Mexico and ceded land come now includes the states of California Nevada Utah New Mexico most of Arizona and Colorado and parts of Oklahoma Kansas and Wyoming to the United States. -

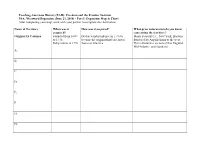

Westward Expansion (June 23, 2014) - Part I: Expansion Map & Chart After Completing Your Map, Work with Your Partner to Complete the Chart Below

Teaching American History (TAH): Freedom and the Frontier Institute PSA: Westward Expansion (June 23, 2014) - Part I: Expansion Map & Chart After completing your map, work with your partner to complete the chart below. Name of Territory When was it How was it acquired? What prior information do you know acquired? concerning the territory? Original 13 Colonies Founded from 1607 Declared independence in 1776 to Major seaports (i.e., New York, Boston) to 1733; become the original thirteen United Bordered by Appalachians to the west Independent in 1776 States of America Three distinctive sections (New England, Mid-Atlantic, and Southern) A: B: C: D: E: F: G: H: Teaching American History (TAH): Freedom and the Frontier Institute PSA: Westward Expansion (June 23, 2014) - Part I: Expansion Map & Chart (Target Responses) After completing your map, work with your partner to complete the chart below. Name of Territory When was it How was it acquired? What prior information do you know acquired? concerning the territory? Original 13 Colonies Founded from 1607 Declared independence in 1776 to become Major seaports (i.e., New York, Boston) to 1733; the original thirteen United States of Bordered by Appalachians to the west Independent in 1776 America Three distinctive sections (New England, Mid-Atlantic, and Southern) A: Trans-Appalachia 1783 Ceded by Great Britain to the U.S. in the Can include any relevant information on Treaty of Paris that ended the geography, history, economy, etc. Revolutionary War B: Louisiana Purchase 1803 Purchased for $15 million from France to secure control of New Orleans and promote national security C: Red River Valley 1818 Ceded by Great Britain as part of the (North) British-American Convention that established the 49th parallel as a border D: Florida 1819 Purchased from Spain after Andrew Jackson’s invasion of the territory made it clear that Spain could not hold it E: Texas 1845 Independent republic since the Texas Revolution in 1836; annexed by the U.S. -

Gadsden Purchase, 1853–1854

7/21/19, 7(21 PM Page 1 of 1 Search... Home Historical Documents Department History Guide to Countries More Resources About Us Home › Milestones › 1830-1860 › Gadsden Purchase, 1853–1854 MILESTONES: 1830–1860 NOTE TO READERS TABLE OF CONTENTS “Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations” has been retired and is no longer maintained. For more 1830–1860: Diplomacy and information, please see the full notice. Westward Expansion Indian Treaties and the Removal Act of 1830 Gadsden Purchase, The Amistad Case, 1839 1853–1854 The Opening to China Part I: the First Opium War, the The Gadsden Purchase, or Treaty, was an agreement between United States, and the Treaty the United States and Mexico, finalized in 1854, in which the of Wangxia, 1839–1844 United States agreed to pay Mexico $10 million for a 29,670 square mile portion of Mexico that later became part of Arizona Webster-Ashburton Treaty, and New Mexico. Gadsden’s Purchase provided the land 1842 necessary for a southern transcontinental railroad and attempted to resolve conflicts that lingered after the Mexican- The Oregon Territory, 1846 American War. The Annexation of Texas, the Mexican-American War, and the Treaty of Guadalupe- Hidalgo, 1845–1848 Founding of Liberia, 1847 United States Maritime Expansion across the Pacific during the 19th Century Gadsden Purchase, 1853– Map Depicting the Gadsden Purchase 1854 While the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo formally ended the Mexican-American War in February 1848, tensions between The United States and the Opening to Japan, 1853 the Governments of Mexico and the United States continued to simmer over the next six years. -

DIFFERENTIATING INSTRUCTION: TIERED ACTIVITIES Impact of Victory

CHAPTER 13 • SECTION 3 Connecting History Meanwhile, Americans in northern California staged a revolt and raised a crude flag featuring a grizzly bear. The revolt, known as the Bear Flag Revolt, Not all war declarations was joined by explorer John C. Frémont. The rebels declared independence have been as contentious as the war against Mexico. from Mexico and formed the Republic of California. U.S. troops joined forces More About . Representative Jeanette with the rebels. Within weeks, American forces controlled all of California. Rankin of Montana, the The Fighting in Mexico The defeat of Mexico proved more difficult. Ameri- first woman in Congress Victory Outside Mexico City and an avowed pacifist, can forces invaded Mexico from two directions. Taylor battled his way south Outside of Mexico City, Winfield Scott’s was the only member of from Texas toward Monterrey in northern Mexico. On February 23, 1847, his the House to vote against 4,800 troops met Santa Anna’s 15,000 Mexican soldiers near a ranch called army fought Mexican troops in the Battle World War II. Buena Vista. After two bloody days of fighting, Santa Anna retreated. The war of Chapultepec. Scott’s troops stormed the in the north of Mexico was over. former palace of Chapultepec, a fortress on In southern Mexico, Winfield Scott‘s forces landed at Veracruz on the Gulf the western side of Mexico City, after more of Mexico and made for Mexico City. Outside the capital, the Americans met than a day of artillery shelling and great loss fierce resistance. But Mexico City fell to Scott in September 1847. -

3 Garrisoning of the Southwest

Contents “Manifest Destiny” ........................................................................................................ 4 Outpost in Apacheria .................................................................................................. 10 The Apache as W arrior ................................................................................................ 12 Dragoons: Garrisoning the Gadsden Purchase ...................................................... 18 Outposts: Tactics in the Apache Campaigns ........................................................... 20 Outposts: Col. Bonneville and the ............................................................................ 33 1857 Battle of the Gila River ....................................................................................... 33 Outposts: The U.S. Army in the Pimeria Alta ........................................................... 36 Voices: Bald y Ewell at For t Buchanan...................................................................... 43 Outposts: The Navaho Campaigns of 1858-60 ......................................................... 44 Roll Call: Sarah Bowman—The Great W estern ........................................................ 49 Outposts: The Anglo Settlers .................................................................................... 51 The Rancher ................................................................................................................. 51 The Miner ....................................................................................................................