Exploring Discourses of Indigeneity and Rurality in Mikea Forest Environmental Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar Is Recruiting for the Following Position

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar is recruiting for the following position: TEMPORARY LANGUAGE AND CROSS-CULTURAL FACILITATORS (LCF) The position is based at the Peace Corps Training Center, in Mantasoa, and is a short-term contract (typically 10 to 14 weeks). The primary role of the LCF is to train American trainees and volunteers in the Malagasy language and culture. Training usually take place at a residential training facilities where both LCFs and trainees/volunteers stay full-time. LCFs work under the direct supervision of Peace Corps Madagascar’s Language Coordinator. The duties of the LCF include, but are not limited to: Conduct Malagasy language training classes with small groups of American trainees or volunteers. Participate in the preparation of language training materials or resources. Conduct formal sessions and provide ongoing informal instruction and advice to trainees/volunteers regarding cultural adaptation and culturally appropriate behavior Interact with trainees outside of the classroom setting, providing informal training during meals, social events and other periods outside of classroom training Actively participate in staff language training Serve as the cultural model and guide for trainees/volunteers within their communities Establish and maintain a healthy, productive team spirit among the language staff and between support staff and Volunteer trainers Occasionally serve as Malagasy and English interpreters and/or translators. As requested, install the new Volunteers at their permanent sites; and train their community-based tutor as needed Required Qualifications: Completion of secondary school (Minimum BACC) Fluency in English, French and Malagasy Mastery in at least one of the following dialects: Betsileo, Antakarana, Antambahoaka, Antemoro, Antesaka, Antefasy, Sakalava boina, Antanosy, Antandroy, Sihanaka, Mahafaly, Bara. -

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic Versus Emblematic Criteria

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic versus Emblematic Criteria Alexander Adelaar UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE This paper gives an overview of the literature on Malagasy dialect variety and the various Malagasy dialect classifications that have been proposed. It rejects the often held view that the way Malagasy dialects reflect the Proto- Austronesian phoneme sequences *li and *ti is a basic criterion for their genetic division. While the linguistic innovations shown in, respectively, central dialects (Merina, Betsileo, Sihanaka, Tanala) and southwestern dia- lects (Vezo, Mahafaly, Tandroy) clearly show that these groups form separate historical divisions, the linguistic developments in other (northern, eastern, and western) dialects are more difficult to interpret. The differences between Malagasy dialects are generally rather contained and do not seem to be the result of separate migration waves or the arrival of linguistically different migrant groups. The paper ends with a list of subgrouping criteria that will be useful for future research into the history of Malagasy dialects. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 This paper investigates some of the early linguistic changes that have contributed to the dialect diversity of Malagasy, as well as the various classifications that have been proposed for Malagasy dialects. Malagasy is an Austronesian language directly related to some of the languages spoken in Central Kalimantan Province and South Kalimantan Province in Indonesian Borneo. Together with these languages, it forms the South East Barito (henceforth SEB) subgroup, which belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. A historical classification of dialects or languages should be based in the first place on the oldest linguistic changes that have happened in the dialect or language group in ques- tion. -

'The Vezo Are Not a Kind of People'. Identity, Difference and 'Ethnicity' Among a Fishing People of Western Madagascar

LSE Research Online Article (refereed) Rita Astuti 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar Originally published in American ethnologist, 22 (3). pp. 464-482 © 1995 by the Regents of the University of California on behalf of the American Ethnological Society. You may cite this version as: Astuti, Rita (1995). 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar [online]. London: LSE Research Online. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/archive/00000470 Available online: November 2005 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the publisher’s version remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk Contact LSE Research Online at: [email protected] 1 `THE VEZO ARE NOT A KIND OF PEOPLE' IDENTITY, DIFFERENCE AND `ETHNICITY' AMONG A FISHING PEOPLE OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR Rita Astuti London School of Economics Acknowledgments Fieldwork was conducted in two Vezo villages, Betania and Belo-sur Mer, between November 1987 and June 1989. -

Expanded PDF Profile

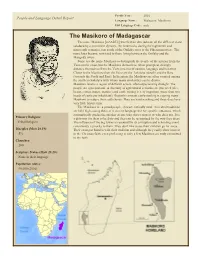

Profile Year: 2001 People and Language Detail Report Language Name: Malagasy, Masikoro ISO Language Code: msh The Masikoro of Madagascar The name Masikoro [mASikUr] was first used to indicate all the different clans subdued by a prominent dynasty, the Andrevola, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, just south of the Onilahy river to the Fiherenana river. The name later became restricted to those living between the Onilahy and the Mangoky rivers. Some use the name Masikoro to distinguish the people of the interior from the Vezo on the coast, but the Masikoro themselves, when prompted, strongly distance themselves from the Vezo in terms of custom, language and behavior. Closer to the Masikoro than the Vezo are the Tañalaña (South) and the Bara (towards the North and East). In literature the Masikoro are often counted among the southern Sakalava with whom many similarities can be drawn. Masikoro land is a region of difficult access, often experiencing drought. The people are agro-pastoral. A diversity of agricultural activities are practiced (rice, beans, cotton, maize, manioc) and cattle raising is very important (more than two heads of cattle per inhabitant). Recently rampant cattle-rustling is causing many Masikoro to reduce their cattle herds. They are hard-working and these days have very little leisure time. The Masikoro are a proud people, characteristically rural. Ancestral traditions are held high among them as is correct language use for specific situations, which automatically grades the speaker as one who shows respect or who does not. It is Primary Religion: a dishonor for them to be dirty and they can be recognized by the way they dress. -

Fombandrazana Vezo: Ethnic Identity and Subsistence

FOMBANDRAZANA VEZO: ETHNIC IDENTITY AND SUBSISTENCE STRATEGIES AMONG COASTAL FISHERS OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR by EARL FURMAN SANDERS (Under the Direction of THEODORE GRAGSON) ABSTRACT The complex dynamic among coastal peoples of western Madagascar involves spread of cultural elements due to extensive seasonal migrations, tribes and ethnic groups merging into progressively broader ethnic groups, distinctions based on interethnic and intra-ethnic boundaries, and lumping of peoples with remotely similar subsistence patterns which has perpetuated ethnonym vagaries. This study analyzes the cultural bases of the Vezo, a group of marine fishers inhabiting the west coast of Madagascar, with the intent of presenting a clearer image of what is entailed within the ethnonym, Vezo, both with respect to subsistence strategies and cultural identity. Three broad areas of inquiry, ethnohistory, ecological niche as understood from the Eltonian definition, and geographical scope inform the field research. Access to these areas leans heavily on oral histories, which in turn is greatly facilitated by intensive participant observation and work in the native language. The analysis shows that the Vezo constitute a distinct ethnic group composed of diverse named patrilineal descent groups. This ethnic group is defined by common origins and a shared sense of common history, which along with the origins of the taboos are maintained within their oral histories. Within the ethnonym, Vezo, there are subsistence as well as other cultural distinctions, most notably the taboos. These distinctions are the bases of the ethnic boundaries separating those who belong to the Vezo cultural group and others who are referred to as Vezo (Vezom-potake and Vezo-loatse) due to geographical disposition. -

The Origins of the Malagasy People, Some Certainties and a Few Mysteries

Instituto de Estudos Avanc¸ados Transdisciplinares Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais The origins of the Malagasy people, some certainties and a few mysteries Maurizio Serva1 Abstract The Malagasy language belongs to the Greater Barito East group of the Austronesian family, the language most closely connected to Malagasy dialects is Maanyan (Kalimantan), but Malay as well other Indonesian and Philippine languages are also related. The African contribution is very high in the Malagasy genetic make-up (about 50%) but negligible in the language. Because of the linguistic link, it is widely accepted that the island was settled by Indonesian sailors after a maritime trek but date and place of landing are still debated. The 50% Indonesian genetic contribution to present Malagasy points in a different direction then Maanyan for the Asian ancestry, therefore, the ethnic composition of the Austronesian settlers is also still debated. In this talk I mainly review the joint research of Filippo Petroni, Dima Volchenkov, Soren¨ Wichmann and myself which tries to shed new light on these problems. The key point is the application of a new quantitative methodology which is able to find out the kinship relations among languages (or dialects). New techniques are also introduced in order to extract the maximum information from these relations concerning time and space patterns. Keywords Malagasy dialects — Austronesian languages — Lexicostatistics — Malagasy origins 1Dipartimento di Ingegneria e Scienze dell’Informazione e Matematica, Universita` dell’Aquila, I-67010 L’Aquila, Italy 1. Introduction The Austronesian expansion, which very likely started from Taiwan or from the south of China [Gray and Jordan, 2000, Hurles et al 2005], is probably the most spectacular event of maritime colonization in human history as it can be appreci- ated in Fig. -

Ea71232020revised May2019b

Tucker, B. (2020). Où vivre sans boire revisited: Water and political-economic change among Mikea hunter- gatherers of southwestern Madagascar. Economic Anthropology 7(1):22-37. Où vivre sans boire revisited: Water and political-economic change among Mikea hunter-gatherers of southwestern Madagascar In this article, I present a political-ecological history of the Mikea Forest of southwestern Madagascar, and of Mikea people, anchored four water-themed moments: 1966, with the publication of one of the first ethnographic descriptions of Mikea, Où vivre sans boire, “where they live without drinking” (Molet 1966); 1998, when Mikea combined foraging with swidden maize agriculture and traveled long distances to get their water; 2003, when a Joint Commission of organizations, working to halt deforestation, considered plans for canals to irrigate potential farmland; and 2018, when Mikea living on the edge of a new national park desperately waited for rain. I offer “hydrosocial moments” as a way to extend Boelens and colleagues’ (2016) “hydrosocial territories” through time. Water facts and truths change through a dialectical process of truth-assertion and contradiction. In the Mikea case, one changing truth was who Mikea are: exotic desert hunter-gatherers, victimized indigenous peoples losing forest to rapacious farmers, or poor people in need of development. Interveners borrowed truths from neighboring hydrosocial territories. The concepts of hydrosocial territories and moments are significant because they have real effects; in this case, poverty. Keywords: Water; hydrosocial territories; hunter-gatherers; Madagascar 2 Introduction The first moment: 1966 In 1966, only six years after Madagascar gained its independence from France, Canadian scholar Louis Molet published one of the first ethnographic descriptions of Mikea people, entitled, Où vivre sans boire, “where one lives without drinking” (Molet 1966). -

Spirometric Reference Values for Malagasy Adults Aged 18–73 Years

ORIGINAL ARTICLE LUNG FUNCTION Spirometric reference values for Malagasy adults aged 18–73 years Julia Ratomaharo1,7, Olinto Linares Perdomo2,7, Dave S. Collingridge3, Rabezanahary Andriamihaja4, Matthew Hegewald2,5, Robert L. Jensen2,5, John Hankinson6 and Alan H. Morris2,5 Affiliations: 1Service de Pneumologie, Hôpital Privé d’Athis-Mons, Athis-Mons, France. 2Pulmonary and Critical Care Division, Dept of Medicine, Intermountain Medical Center, Murray, UT, USA. 3Office of Research, Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 4Service de Pneumologie, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Toamasina, Toamasina, Madagascar. 5University of Utah, School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 6Hankinson Consulting, Inc., Athens, GA, USA. 7Both authors contributed equally. Correspondence: Olinto Linares Perdomo, Pulmonary/Critical Care Division, Sorenson Heart and Lung Center, 6th Floor, Intermountain Medical Center, 5121 South Cottonwood Street, Murray, UT 84157-7000, USA. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS) recommend that spirometry prediction equations be derived from samples of similar race/ethnicity. Malagasy prediction equations do not exist. The objectives of this study were to establish prediction equations for healthy Malagasy adults, and then compare Malagasy measurements with published prediction equations. We enrolled 2491 healthy Malagasy subjects aged 18–73 years (1428 males) from June 2006 to April 2008. The subjects attempted to meet the ATS/ERS 2005 guidelines when performing forced expiratory spirograms. We compared Malagasy measurements of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and FEV1/FVC with predictions from the European Community for Steel and Coal (ECSC), the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) and the ERS Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) 2012 study. -

How to Read a Folktale: the 'Ibonia' Epic from Madagascar

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/109 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. A Merina performer of the highlands. Photo by Lee Haring (1975). World Oral Literature Series: Volume 4 How to Read a Folktale: The Ibonia Epic from Madagascar Translation and Reader’s Guide by Lee Haring http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Lee Haring; Foreword © 2013 Mark Turin This book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license (CC-BY 3.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work. The work must be attributed to the respective authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Lee Haring, How to Read a Folktale: The Ibonia Epic from Madagascar. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2013. DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0034 Further copyright and licensing details are available at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254053 This is the fourth volume in the World Oral Literature Series, published in association with the World Oral Literature Project. World Oral Literature Series: ISSN: 2050-7933 As with all Open Book Publishers titles, digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254053 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-06-0 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-05-3 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-909254-07-7 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-08-4 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-09-1 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0034 Cover image: Couple (Hazomanga?), sculpture in wood and pigment. -

SAGA Working Paper April 2007 Agricultural Technology, Productivity, Poverty and Food Security in Madagascar

SAGA Working Paper April 2007 Agricultural Technology, Productivity, Poverty and Food Security in Madagascar Bart Minten Cornell University Christopher B. Barrett Cornell University Strategies and Analysis for Growth and Access (SAGA) is a project of Cornell and Clark Atlanta Universities, funded by cooperative agreement #HFM‐A‐00‐01‐00132‐ 00 with the United States Agency for International Development. Agricultural Technology, Productivity, and Poverty in Madagascar Bart Minten International Food Policy Research Institute and Christopher B. Barrett§ Cornell University § Corresponding author: 315 Warren Hall, Department of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853-7801 USA, telephone: 1-607-255- 4489, email: [email protected], fax: 1-607-255-9984. © Copyright 2007 by the authors. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. Agricultural Technology, Productivity, and Poverty in Madagascar Abstract This paper uses a unique, spatially-explicit dataset to study the link between agricultural performance and rural poverty in Madagascar. We show that, controlling for geographical and physical characteristics, communes that have higher rates of adoption of improved agricultural technologies and, consequently, higher crop yields enjoy lower food prices, higher real wages for unskilled workers and better welfare indicators. The empirical evidence strongly favors support for improved agricultural production as an important part of any strategy to reduce the high poverty and food insecurity rates currently prevalent in rural Madagascar. Keywords: Poverty, agriculture, technology adoption, spatial analysis, Sub-Saharan Africa, Madagascar 1 Acknowledgements: We thank Luc Christiaensen for his continuous help throughout this project. -

International Human Rights Instruments Have Been Incorporated Into the 1992 Constitution;

UNITED NATIONS HRI International Distr. Human Rights GENERAL Instruments HRI/CORE/1/Add.31/Rev.1 18 May 2004 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH CORE DOCUMENT FORMING THE INITIAL PART OF THE REPORTS OF STATES PARTIES MADAGASCAR [30 December 2003] GE.04-41789 (E) 210604 250604 HRI/CORE/1/Add.31/Rev.1 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page I. TERRITORY ................................................................................ 1 - 4 4 A. Geography ......................................................................... 1 - 3 4 B. Administrative organization .............................................. 4 4 II. POPULATION .............................................................................. 5 - 9 5 A. History ............................................................................... 5 5 B. Ethnic groups and language............................................... 6 - 8 5 C. Foreign communities......................................................... 9 5 III. DEMOGRAPHY........................................................................... 10 - 18 5 A. Main demographic characteristics..................................... 10 - 12 5 B. Distribution of the population ........................................... 13 - 15 6 C. Main demographic indicators ............................................ 16 - 18 9 IV. INFRASTRUCTURE.................................................................... 19 - 23 10 V. GENERAL POLITICAL STRUCTURE....................................... 24 - 27 12 VI. GENERAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK WITHIN WHICH HUMAN RIGHTS ARE -

The Settlement of Madagascar: What Dialects and Languages Can Tell Us

The Settlement of Madagascar: What Dialects and Languages Can Tell Us Maurizio Serva* Dipartimento di Matematica, Universita` dell’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy Abstract The dialects of Madagascar belong to the Greater Barito East group of the Austronesian family and it is widely accepted that the Island was colonized by Indonesian sailors after a maritime trek that probably took place around 650 CE. The language most closely related to Malagasy dialects is Maanyan, but Malay is also strongly related especially for navigation terms. Since the Maanyan Dayaks live along the Barito river in Kalimantan (Borneo) and they do not possess the necessary skill for long maritime navigation, they were probably brought as subordinates by Malay sailors. In a recent paper we compared 23 different Malagasy dialects in order to determine the time and the landing area of the first colonization. In this research we use new data and new methods to confirm that the landing took place on the south-east coast of the Island. Furthermore, we are able to state here that colonization probably consisted of a single founding event rather than multiple settlements.To reach our goal we find out the internal kinship relations among all the 23 Malagasy dialects and we also find out the relations of the 23 dialects to Malay and Maanyan. The method used is an automated version of the lexicostatistic approach. The data from Madagascar were collected by the author at the beginning of 2010 and consist of Swadesh lists of 200 items for 23 dialects covering all areas of the Island. The lists for Maanyan and Malay were obtained from a published dataset integrated with the author’s interviews.