Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic Versus Emblematic Criteria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Accent and Intonation in a Malagasy Dialect. Raoniarisoa, Noro

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Accent and intonation in a Malagasy dialect. Raoniarisoa, Noro Award date: 1990 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 ACCENT AND INTONATION IN A MALAGASY DIALECT A Thesis submitted to the University of Wales by Noro RAONIARISOA in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of English and Linguistics University College of North Wales Bangor 1990 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to Dr. F. Gooding, my supervisor, for his valuable criticism and encouragement, and to his wife, Judy, for her kindness. My thanks are also due to the members of the Linguistics staff at the School of English and Linguistics in Bangor who, in one way or another, helped me at different stages of my research. The Malagasy Lutheran Church and the Norwegian Missionary Society have provided the financial support which has enabled me to do this research and I express my sincere gratitude to them. -

The Linguistic Background to SE Asian Sea Nomadism

The linguistic background to SE Asian sea nomadism Chapter in: Sea nomads of SE Asia past and present. Bérénice Bellina, Roger M. Blench & Jean-Christophe Galipaud eds. Singapore: NUS Press. Roger Blench McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Department of History, University of Jos Correspondence to: 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: Cambridge, March 21, 2017 Roger Blench Linguistic context of SE Asian sea peoples Submission version TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. The broad picture 3 3. The Samalic [Bajau] languages 4 4. The Orang Laut languages 5 5. The Andaman Sea languages 6 6. The Vezo hypothesis 9 7. Should we include river nomads? 10 8. Boat-people along the coast of China 10 9. Historical interpretation 11 References 13 TABLES Table 1. Linguistic affiliation of sea nomad populations 3 Table 2. Sailfish in Moklen/Moken 7 Table 3. Big-eye scad in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 4. Lake → ocean in Moklen 8 Table 5. Gill-net in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 6. Hearth on boat in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 7. Fishtrap in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 8. ‘Bracelet’ in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 9. Vezo fish names and their corresponding Malayopolynesian etymologies 9 FIGURES Figure 1. The Samalic languages 5 Figure 2. Schematic model of trade mosaic in the trans-Isthmian region 12 PHOTOS Photo 1. Orang Laut settlement in Riau 5 Photo 2. -

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar Is Recruiting for the Following Position

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar is recruiting for the following position: TEMPORARY LANGUAGE AND CROSS-CULTURAL FACILITATORS (LCF) The position is based at the Peace Corps Training Center, in Mantasoa, and is a short-term contract (typically 10 to 14 weeks). The primary role of the LCF is to train American trainees and volunteers in the Malagasy language and culture. Training usually take place at a residential training facilities where both LCFs and trainees/volunteers stay full-time. LCFs work under the direct supervision of Peace Corps Madagascar’s Language Coordinator. The duties of the LCF include, but are not limited to: Conduct Malagasy language training classes with small groups of American trainees or volunteers. Participate in the preparation of language training materials or resources. Conduct formal sessions and provide ongoing informal instruction and advice to trainees/volunteers regarding cultural adaptation and culturally appropriate behavior Interact with trainees outside of the classroom setting, providing informal training during meals, social events and other periods outside of classroom training Actively participate in staff language training Serve as the cultural model and guide for trainees/volunteers within their communities Establish and maintain a healthy, productive team spirit among the language staff and between support staff and Volunteer trainers Occasionally serve as Malagasy and English interpreters and/or translators. As requested, install the new Volunteers at their permanent sites; and train their community-based tutor as needed Required Qualifications: Completion of secondary school (Minimum BACC) Fluency in English, French and Malagasy Mastery in at least one of the following dialects: Betsileo, Antakarana, Antambahoaka, Antemoro, Antesaka, Antefasy, Sakalava boina, Antanosy, Antandroy, Sihanaka, Mahafaly, Bara. -

Interdisciplinary Approaches to Stratifying the Peopling of Madagascar

INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACHES TO STRATIFYING THE PEOPLING OF MADAGASCAR Paper submitted for the proceedings of the Indian Ocean Conference, Madison, Wisconsin 23-24th October, 2015 Roger Blench McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Correspondence to: 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This version: Makurdi, 1 April, 2016 1 Malagasy - Sulawesi lexical connections Roger Blench Submission version TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................................. i ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................................ii 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Models for the settlement of Madagascar ................................................................................................. 2 3. Linguistic evidence...................................................................................................................................... 2 3.1 Overview 2 3.2 Connections with Sulawesi languages 3 3.2.1 Nouns.............................................................................................................................................. -

1646 KMS Kenya Past and Present Issue 46.Pdf

Kenya Past and Present ISSUE 46, 2019 CONTENTS KMS HIGHLIGHTS, 2018 3 Pat Jentz NMK HIGHLIGHTS, 2018 7 Juliana Jebet NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS 13 AT MT. ELGON CAVES, WESTERN KENYA Emmanuel K. Ndiema, Purity Kiura, Rahab Kinyanjui RAS SERANI: AN HISTORICAL COMPLEX 22 Hans-Martin Sommer COCKATOOS AND CROCODILES: 32 SEARCHING FOR WORDS OF AUSTRONESIAN ORIGIN IN SWAHILI Martin Walsh PURI, PAROTHA, PICKLES AND PAPADAM 41 Saryoo Shah ZANZIBAR PLATES: MAASTRICHT AND OTHER PLATES 45 ON THE EAST AFRICAN COAST Villoo Nowrojee and Pheroze Nowrojee EXCEPTIONAL OBJECTS FROM KENYA’S 53 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES Angela W. Kabiru FRONT COVER ‘They speak to us of warm welcomes and traditional hospitality, of large offerings of richly flavoured rice, of meat cooked in coconut milk, of sweets as generous in quantity as the meals they followed.’ See Villoo and Pheroze Nowrojee. ‘Zanzibar Plates’ p. 45 1 KMS COUNCIL 2018 - 2019 KENYA MUSEUM SOCIETY Officers The Kenya Museum Society (KMS) is a non-profit Chairperson Pat Jentz members’ organisation formed in 1971 to support Vice Chairperson Jill Ghai and promote the work of the National Museums of Honorary Secretary Dr Marla Stone Kenya (NMK). You are invited to join the Society and Honorary Treasurer Peter Brice receive Kenya Past and Present. Privileges to members include regular newsletters, free entrance to all Council Members national museums, prehistoric sites and monuments PR and Marketing Coordinator Kari Mutu under the jurisdiction of the National Museums of Weekend Outings Coordinator Narinder Heyer Kenya, entry to the Oloolua Nature Trail at half price Day Outings Coordinator Catalina Osorio and 5% discount on books in the KMS shop. -

Men and Women of the Forest. Livelihood Strategies And

Men and women of the forest Livelihood strategies and conservation from a gender perspective in Ranomafana National Park, Madagascar Laura Järvilehto Master’s thesis in Environmental Sciences Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences University of Helsinki November 2005 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Faculty of Biosciences Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences Tekijä – Författare – Author Laura Järvilehto Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Men and women of the forest – Livelihood strategies and conservation from a gender perspective in Ranomafana National Park, Madagascar Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Environmental Sciences Työn laji– Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä – Sidoantal – Number of pages Master’s thesis November 2005 50 pages Tiivistelmä Referat – Abstract The objective of this study is twofold: Firstly, to investigate how men and women living in Tanala villages in the Ranomafana National Park buffer zone differ in their natural resource use and livelihood. Secondly, based on this information, the intention is to find out how the establishment of the park has influenced people living in the buffer zone from the gender point of view. The data have been gathered mainly by using semi-structured interviews. Group interviews and individual interviews were carried out in three buffer zone villages. In addition, members of the park personnel were interviewed, observations were made during the visits to the villages and documents related to the planning and the administration of the park were investigated. The data were analysed using qualitative content analysis. It seems that Tanala women and men relate to their environment in a rather similar way and that they have quite equal rights considering the use and the control of natural resources. -

'The Vezo Are Not a Kind of People'. Identity, Difference and 'Ethnicity' Among a Fishing People of Western Madagascar

LSE Research Online Article (refereed) Rita Astuti 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar Originally published in American ethnologist, 22 (3). pp. 464-482 © 1995 by the Regents of the University of California on behalf of the American Ethnological Society. You may cite this version as: Astuti, Rita (1995). 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar [online]. London: LSE Research Online. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/archive/00000470 Available online: November 2005 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the publisher’s version remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk Contact LSE Research Online at: [email protected] 1 `THE VEZO ARE NOT A KIND OF PEOPLE' IDENTITY, DIFFERENCE AND `ETHNICITY' AMONG A FISHING PEOPLE OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR Rita Astuti London School of Economics Acknowledgments Fieldwork was conducted in two Vezo villages, Betania and Belo-sur Mer, between November 1987 and June 1989. -

Expanded PDF Profile

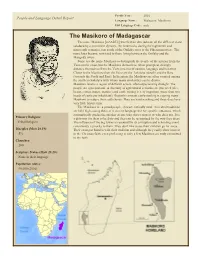

Profile Year: 2001 People and Language Detail Report Language Name: Malagasy, Masikoro ISO Language Code: msh The Masikoro of Madagascar The name Masikoro [mASikUr] was first used to indicate all the different clans subdued by a prominent dynasty, the Andrevola, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, just south of the Onilahy river to the Fiherenana river. The name later became restricted to those living between the Onilahy and the Mangoky rivers. Some use the name Masikoro to distinguish the people of the interior from the Vezo on the coast, but the Masikoro themselves, when prompted, strongly distance themselves from the Vezo in terms of custom, language and behavior. Closer to the Masikoro than the Vezo are the Tañalaña (South) and the Bara (towards the North and East). In literature the Masikoro are often counted among the southern Sakalava with whom many similarities can be drawn. Masikoro land is a region of difficult access, often experiencing drought. The people are agro-pastoral. A diversity of agricultural activities are practiced (rice, beans, cotton, maize, manioc) and cattle raising is very important (more than two heads of cattle per inhabitant). Recently rampant cattle-rustling is causing many Masikoro to reduce their cattle herds. They are hard-working and these days have very little leisure time. The Masikoro are a proud people, characteristically rural. Ancestral traditions are held high among them as is correct language use for specific situations, which automatically grades the speaker as one who shows respect or who does not. It is Primary Religion: a dishonor for them to be dirty and they can be recognized by the way they dress. -

A Strategy to Reach Animistic People in Madagascar

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2006 A Strategy To Reach Animistic People in Madagascar Jacques Ratsimbason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Ratsimbason, Jacques, "A Strategy To Reach Animistic People in Madagascar" (2006). Dissertation Projects DMin. 690. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/690 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A STRATEGY TO REACH ANIMISTIC PEOPLE IN MADAGASCAR by Jacques Ratsimbason Adviser: Bruce Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A STRATEGY TO REACH ANIMISTIC PEOPLE IN MADAGASCAR Name of researcher: Jacques Ratsimbason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Bruce Bauer, D.Miss. Date completed: August 2006 Problem The majority of the Malagasy people who live in Madagascar are unreached with the gospel message. A preliminary investigation of current literature indicated that 50 percent of the Malagasy are followers of traditional religions. This present study was to develop a strategy to reach the animistic people with the gospel message. Method This study presents Malagasy people, their social characteristics, population, worldviews, and lifestyles. A study;and evaluation of Malagasy beliefs and practices were developed using Hiebert's model of critical contextualization. Results The study reveals that the Seventh-day Adventist Church must update its evangelistic methods to reach animistic people and finish the gospel commission in Madagascar. -

Fombandrazana Vezo: Ethnic Identity and Subsistence

FOMBANDRAZANA VEZO: ETHNIC IDENTITY AND SUBSISTENCE STRATEGIES AMONG COASTAL FISHERS OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR by EARL FURMAN SANDERS (Under the Direction of THEODORE GRAGSON) ABSTRACT The complex dynamic among coastal peoples of western Madagascar involves spread of cultural elements due to extensive seasonal migrations, tribes and ethnic groups merging into progressively broader ethnic groups, distinctions based on interethnic and intra-ethnic boundaries, and lumping of peoples with remotely similar subsistence patterns which has perpetuated ethnonym vagaries. This study analyzes the cultural bases of the Vezo, a group of marine fishers inhabiting the west coast of Madagascar, with the intent of presenting a clearer image of what is entailed within the ethnonym, Vezo, both with respect to subsistence strategies and cultural identity. Three broad areas of inquiry, ethnohistory, ecological niche as understood from the Eltonian definition, and geographical scope inform the field research. Access to these areas leans heavily on oral histories, which in turn is greatly facilitated by intensive participant observation and work in the native language. The analysis shows that the Vezo constitute a distinct ethnic group composed of diverse named patrilineal descent groups. This ethnic group is defined by common origins and a shared sense of common history, which along with the origins of the taboos are maintained within their oral histories. Within the ethnonym, Vezo, there are subsistence as well as other cultural distinctions, most notably the taboos. These distinctions are the bases of the ethnic boundaries separating those who belong to the Vezo cultural group and others who are referred to as Vezo (Vezom-potake and Vezo-loatse) due to geographical disposition. -

A Grammar of the Malagasy Language, in the Ankova Dialect

NRLF B ^ EEfi ifio LIBfi/ UNIVE6SI CALIfORNJ ZJL lERKf I £Y \^iii.3 m MALAGASY GRAMMAR. GRAMMAR OF THE MALAGASY LANGUAGE, IN THE ANKOVA DIALECT; BY DAVID GRIFFITHS, Missionary for nearly TAventy years in Madagascar. WOODBRIDGE : FEINTED BY EDWAED PITE, CHURCH STREET, 1854. TO ®Jie i^eb, ^» aa, iWeller, ilW. ^, RECTOR OF WOODBRIDGE, SUPEOLK, AND THE EDITORIAL SUPERINTENDENT OF THE SCRIPTURES FOR THE BRITISH AND FOREIGN BIBLE SOCIETY IN DIFFERENT LANGUAGES, THIS GRAMMAR IS MOST RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED, BY HIS ^ FAITHFUL AND OBEDIENT FRIEND AND SERVANT, OAVID GRIFFITHS. 120 ; PREFACE. IN learning any language, a grammar and voca- bulary are of the utmost importance. Had such help been available, when the writer com- menced the study of the Malagasy tongue, he would have saved much valuable time, and been spared years of painful toil. Having, through long residence in ft Madagascar, acquired a perfect knowledge of its language, the desirableness of undertaking the task of preparing a Grammar has often been pressed on his attention, by many friends of missions at home and abroad. Gentlemen of different christian denomina- tions, offered pecuniary assistance towards this object and some of the most intelligent and best educated of the natives of that important Island, have also ex- pressed a strong wish to see it accomplished. U VI PREFACE. Being, at this present time, engaged in revising the Malagasy translation of the Holy Scriptures, with the valuable assistance of the Rev. T. W. Meller, M. A., Rector of Woodbridge, and having to give constant attention to the structure and rules of the language, it appeared to the author to be a suitable opportunity for pursuing his long-cherished purpose. -

INDO 92 0 1319755155 59 96.Pdf (1006.Kb)

"The Single Most Astonishing Fact of Human Geography": Indonesia's Far W est Colony Ann Kumar The title of this paper is taken from the following paragraph by Jared Diamond: These Austronesians, with their Austronesian language and modified Austronesian culture, were already established on Madagascar by the time it was first visited by Europeans, in 1500. This strikes me as the single most astonishing fact of human geography for the entire world. It's as if Columbus, on reaching Cuba, had found it occupied by blue-eyed, blond-haired Scandinavians speaking a language close to Swedish, even though the nearby North American continent was inhabited by Native Americans speaking Amerindian languages. How on earth could prehistoric people from Borneo, presumably voyaging on boats without maps or compasses, end up in Madagascar?1 Though he regards the presence of these "prehistoric people from Borneo" on the isolated island of Madagascar as the most astonishing fact of human geography, Diamond does not, to his credit, dismiss it as impossible: he recognizes the strength of the evidence. Not only do Madagascans look astonishingly like Indonesians, they also speak a language that derives from Borneo (Kalimantan). This paper surveys the long series of studies that established this linguistic relationship and deals with a number of different types of evidence not examined by Diamond. It is hoped that this will answer 1 Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years (London: Vintage, 1998), p. 381. Indonesia 92 (October 2011) 60 Ann Kumar his "how on earth" question, and it may be possible to answer the "why on earth" question as well.