Men and Women of the Forest. Livelihood Strategies And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic Versus Emblematic Criteria

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic versus Emblematic Criteria Alexander Adelaar UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE This paper gives an overview of the literature on Malagasy dialect variety and the various Malagasy dialect classifications that have been proposed. It rejects the often held view that the way Malagasy dialects reflect the Proto- Austronesian phoneme sequences *li and *ti is a basic criterion for their genetic division. While the linguistic innovations shown in, respectively, central dialects (Merina, Betsileo, Sihanaka, Tanala) and southwestern dia- lects (Vezo, Mahafaly, Tandroy) clearly show that these groups form separate historical divisions, the linguistic developments in other (northern, eastern, and western) dialects are more difficult to interpret. The differences between Malagasy dialects are generally rather contained and do not seem to be the result of separate migration waves or the arrival of linguistically different migrant groups. The paper ends with a list of subgrouping criteria that will be useful for future research into the history of Malagasy dialects. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 This paper investigates some of the early linguistic changes that have contributed to the dialect diversity of Malagasy, as well as the various classifications that have been proposed for Malagasy dialects. Malagasy is an Austronesian language directly related to some of the languages spoken in Central Kalimantan Province and South Kalimantan Province in Indonesian Borneo. Together with these languages, it forms the South East Barito (henceforth SEB) subgroup, which belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. A historical classification of dialects or languages should be based in the first place on the oldest linguistic changes that have happened in the dialect or language group in ques- tion. -

Fombandrazana Vezo: Ethnic Identity and Subsistence

FOMBANDRAZANA VEZO: ETHNIC IDENTITY AND SUBSISTENCE STRATEGIES AMONG COASTAL FISHERS OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR by EARL FURMAN SANDERS (Under the Direction of THEODORE GRAGSON) ABSTRACT The complex dynamic among coastal peoples of western Madagascar involves spread of cultural elements due to extensive seasonal migrations, tribes and ethnic groups merging into progressively broader ethnic groups, distinctions based on interethnic and intra-ethnic boundaries, and lumping of peoples with remotely similar subsistence patterns which has perpetuated ethnonym vagaries. This study analyzes the cultural bases of the Vezo, a group of marine fishers inhabiting the west coast of Madagascar, with the intent of presenting a clearer image of what is entailed within the ethnonym, Vezo, both with respect to subsistence strategies and cultural identity. Three broad areas of inquiry, ethnohistory, ecological niche as understood from the Eltonian definition, and geographical scope inform the field research. Access to these areas leans heavily on oral histories, which in turn is greatly facilitated by intensive participant observation and work in the native language. The analysis shows that the Vezo constitute a distinct ethnic group composed of diverse named patrilineal descent groups. This ethnic group is defined by common origins and a shared sense of common history, which along with the origins of the taboos are maintained within their oral histories. Within the ethnonym, Vezo, there are subsistence as well as other cultural distinctions, most notably the taboos. These distinctions are the bases of the ethnic boundaries separating those who belong to the Vezo cultural group and others who are referred to as Vezo (Vezom-potake and Vezo-loatse) due to geographical disposition. -

An Exploration of the Relationship Between the Environment and Mahafaly Oral Literature

Environment as Social and Literary Constructs: An Exploration of the Relationship between the Environment and Mahafaly Oral Literature * Eugenie Cha 4 May 2007 Project Advisor: Jeanine Rambeloson Location: Ampanihy Program: Madagascar: Culture and Society Term: Spring semester 2007 Program Director: Roland Pritchett Acknowledgements This research would not have been possible without the wonderful assistance and support of those involved. First and foremost, many thanks to Gabriel Rahasimanana, my translator and fellow colleague who accompanied me to Ampanihy; thank you to my advisor, Professor Jeanine Rambeloson and to Professor Manassé Esoavelomandroso of the University of Tana; the Rahaniraka family in Toliara; Professors Barthelemy Manjakahery, Pietro Lupo, Aurélien de Moussa Behavira, and Jean Piso of the University of Toliara; Marie Razanonoro and José Austin; the Rakatolomalala family in Tana for their undying support and graciousness throughout the semester; and to Roland Pritchett for ensuring that this project got on its way. 2 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………4-6 History of Oral Literature in Madagascar…………………………………………......6-8 What is Oral Tradition………………………………………………………………..8-10 The Influence of Linguistic and Ethnic Diversity……………………………….......10-13 Location……………………………………………………………………………...13-14 Methodology………………………………………………………………………...14-17 Findings: How Ampanihy Came to Be………………………………………………17-18 “The Source of Life” and the Sacredness of Nature…………………………………18-21 Mahafaly Stories: Present-day Literature……………………………………….......21-29 1. Etsimangafalahy and Tsimagnolobala………………………………………23 2. The Three Kings………………………………………………………....23-26 3. The Baobab…………………………………………………………….........27 4. The Origins of the Mahafaly and Antandroy…………………………....27-28 5. Mandikalily……………………………………………………………...28-29 Modernization and Oral Literature: Developments and Dilemmas………………....29-33 Synthesis: Analysis of Findings…………………………………………………….33-36 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………...36-38 Appendix………………………………………………………………………………..39 A. -

The First Migrants to Madagascar and Their Introduction of Plants : Linguistic and Ethnological Evidence Philippe Beaujard

The first migrants to Madagascar and their introduction of plants : linguistic and ethnological evidence Philippe Beaujard To cite this version: Philippe Beaujard. The first migrants to Madagascar and their introduction of plants : linguistic and ethnological evidence. Azania : The journal of the British Institute of History and Archaeology in East Africa, Routledge (imprimé) / Taylor & Francis Online (en ligne), 2011, 46 (2), pp.169-189. halshs-00706173 HAL Id: halshs-00706173 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00706173 Submitted on 9 Jun 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. This article was downloaded by: [Beaujard, Philippe] On: 20 June 2011 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 938797940] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t902477532 -

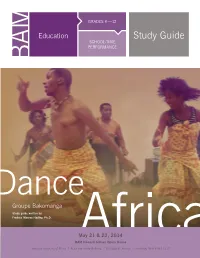

Study Guide SCHOOL-TIME PERFORMANCE

GRADES K—12 Education Study Guide SCHOOL-TIME PERFORMANCE Dance Groupe Bakomanga Study guide written by Fredara Mareva Hadley, Ph.D. May 21 & 22, 2014 BAMAfrica Howard Gilman Opera House Brooklyn Academy of Music / Peter Jay Sharp Building / 30 Lafayette Avenue / Brooklyn, New York 11217 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 3: Madagascar: An Introduction Page 4: Madagascar: An Introduction (continued) Page 5: The Language of Madagascar Enrichment Activity Page 6: Merina Culture Page 7: Religious Performance with Ancestors Page 8: Dance in Madagascar Page 9: Dance in Madagascar (continued) Enrichment Activity Page 10: Malagasy Instruments Page 11: Bakomanga Dance Guide Enrichment Activity Page 12: Glossary Instrument Guide DEAR EDUCATOR Welcome to the study guide for BAM’s DanceAfrica 2014. This year’s events feature Groupe Bakomanga, an acclaimed troupe from Madagascar performing traditional Malagasy music and dance. YOUR VISIT TO BAM The BAM program includes this study guide, a pre-performance workshop, and the performance at BAM’s Howard Gilman Opera House. HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE This guide is designed to connect to the Common Core State Standards with relevant information and activities; to reinforce and encourage critical thinking and analytical skills; and to provide the tools and background information necessary for an engaging and inspiring experience at BAM. Please use these materials and enrich- ment activities to engage students before or after the show. 2 · DANCEAFRICA MADAGASCAR: AN LOCATION AND GEOGRAPHY INTRODUCTION The Republic of Madagascar lies in the Indian Ocean off the Madagascar is a land of contradictions. It is a place that conjures southeastern coast of Africa. -

4. MADAGASCAR Rakotondramihamina Jean De Dieu

4. MADAGASCAR Rakotondramihamina Jean de Dieu 4.1 Introduction Madagascar, an island nation, is situated in Indian Ocean. It was a French colony from 1896 until independence in 1960. It had the good fortune, in the past, to be governed and united under a great sovereign: ANRIANAMPOINIMERINA, who, in the 10 years from 1800 to 1810 succeeded in creating a government worthy of the name. He was succeeded, with varying degrees of success by RADAMA I, RADAMA II, RANAVALONA I, RANAVALONA II, and RANAVALONA III. The last queen was expelled from the country by French in 1895. It has a total area of 592.000 square kilometers with a total population of 14 million, 80 percent of whom live in the rural areas. Moreover, 55 percent of Malagasy people are under 20 age. The ancestor of Malagasy people came from Asia and Africa. Madagascar has 19 tribes which are: Sihanaka, Merina, Antesaka, Antambahoaka, Antandroy, Antefasy, Antemoro, Tsimihety, Bara, Betsileo, Bezanozano, Betsimisarka, Sakalava, Vezo, Mahafaly, Antankarana, Makoa, Tanala, and Antanosy. This implies the existence of different traditions and dialects. However, despite the diversity, Madagascar has a common language namely “ Malagasy Ofisialy”, which constitutes its official language apart from French. Malagasy people are animist. They believe traditionally in only one God “ ZANAHARY”, creator of the universe, the nature and the men. Only 45 percent of the population are Christian. However, there is no border between the two beliefs, since the Christians, Catholic or Protestant, continue to practice the traditional rites. In fact most practice a kind of syncretism with a more or less harmonious combination of monotheism and Ancestor worship. -

The Tanala, a Hill Tribe of Madagascar

Field Museum of Natural History Founded by Marshall Field, 1893 Publication 317 Anthropological Series Volume XXII THE TANALA A HILL TRIBE OF MADAGASCAR BY Ralph Linton PROFESSOR OF ANTHROPOLOGY AT UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN FORMERLY ASSISTANT CURATOR OF OCEANIC AND MALAYAN ETHNOLOGY IN FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Marshall Field Expedition to Madagascar, 1926 35 Text-figures Berthold Laufer CURATOR, DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY EDITOR ( r A NATURAL 1 HISTORY .J> £^;cagO Chicago, U.S.A.THEIWOFTHE 1933 APR 6 1933 UNIVERSITY OF II PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY FIELD MUSEUM PRESS / v. 2.2- CONTENTS PAGE List of Illustrations 7 Preface 15 I. Introduction 17 II. Nature of the Territory 20 III. Tanala Aborigines 22 IV. Composition and Origins of the Present Tribe 24 Divisions of the Ikongo 26 Divisions of the Menabe 34 V. Economic Life 37 Sources of Food 37 Agriculture 37 Domestic Animals 47 Pets 52 Hunting 52 Fishing 56 Honey and Beeswax 59 Wild Vegetable Foods 60 Preparation of Food 62 Fire Making 62 Pottery 66 Methods of Cooking 66 Utensils 70 Customs in Eating 74 Alcohol and Narcotics 75 Manufactures 78 Division of Labor 78 Artisans 78 Metal Working 79 Wood Working 83 Work in Horn, Bone and Hide 86 Matting and Basketry 87 Manufacture of Bark Cloth 95 Manufacture of Cloth 96 Cordage 106 3 Contents Dwellings 107 Artificial Light 115 Costume 115 Transportation 124 Trade 125 Forest Products 126 Property and Inheritance 127 N* VI. Social Organization 132 The Family 132 The Lineage 133 The Village 134 The Gens 136 Social Classes 137 Regulation of Marriage 140 The Levirate 141 Significance of the Bride Price 142 v Inter-Class Marriage and Inheritance of Rank 143 N* Relationship Terms 144 VII. -

Conditions of Change Affecting Mahafale Pastoralists in Southwestern Madagascar

Forests and Thorns: Conditions of Change Affecting Mahafale Pastoralists in Southwestern Madagascar Jeffrey C. Kaufmann and Sylvestre Tsirahamba Abstract: Through two case studies of Mahafale pastoralists living along the Linta River in the spiny forest ecoregion of southwestern Madagascar, the paper explores the human impact on forest cover. While the environmental history of spiny forests along the Linta River indicates anthropogenic changes to forest cover, it also confirms out that forests have long been part of Mahafale landscapes. Thorns and spiny forests have not been inconveniences but preferences, and as much a part of their pastoralist strategies as grass. Two factors affecting forest cover are examined in detail, highlighting both external and internal processes. The first involves the increased sedentarisa- tion of transhumant pastoralists who have integrated the prickly pear cactus into their landscape for use as cattle fodder and as human food. The second concerns the recent displacement of mobile pastoralists by immigrant farmers who made clearings in a large forest held intact by pastoralists as a reserve for livestock during times of stress. In an attempt to understand the complex processes of environmental change along the Linta River we focus our study on flexibility and on accenting a nature–culture mosaic that is largely deter- mined by both ecological and social pressures. Keywords: Madagascar, Mahafale, pastoralism, dry forests, prickly pear cac- tus, anthropogenic change, conservation Joanne Burnett: Translator Jeffrey C. Kaufmann, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Department of Anthropology and Sociology, 118 College Drive #5074, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS 39406-0001 USA. Sylvestre Tsirahamba, Geographer, University of Antananarivo, BP 566, Antananarivo 101, Madagascar. -

Spirometric Reference Values for Malagasy Adults Aged 18–73 Years

ORIGINAL ARTICLE LUNG FUNCTION Spirometric reference values for Malagasy adults aged 18–73 years Julia Ratomaharo1,7, Olinto Linares Perdomo2,7, Dave S. Collingridge3, Rabezanahary Andriamihaja4, Matthew Hegewald2,5, Robert L. Jensen2,5, John Hankinson6 and Alan H. Morris2,5 Affiliations: 1Service de Pneumologie, Hôpital Privé d’Athis-Mons, Athis-Mons, France. 2Pulmonary and Critical Care Division, Dept of Medicine, Intermountain Medical Center, Murray, UT, USA. 3Office of Research, Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 4Service de Pneumologie, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Toamasina, Toamasina, Madagascar. 5University of Utah, School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 6Hankinson Consulting, Inc., Athens, GA, USA. 7Both authors contributed equally. Correspondence: Olinto Linares Perdomo, Pulmonary/Critical Care Division, Sorenson Heart and Lung Center, 6th Floor, Intermountain Medical Center, 5121 South Cottonwood Street, Murray, UT 84157-7000, USA. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS) recommend that spirometry prediction equations be derived from samples of similar race/ethnicity. Malagasy prediction equations do not exist. The objectives of this study were to establish prediction equations for healthy Malagasy adults, and then compare Malagasy measurements with published prediction equations. We enrolled 2491 healthy Malagasy subjects aged 18–73 years (1428 males) from June 2006 to April 2008. The subjects attempted to meet the ATS/ERS 2005 guidelines when performing forced expiratory spirograms. We compared Malagasy measurements of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and FEV1/FVC with predictions from the European Community for Steel and Coal (ECSC), the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) and the ERS Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) 2012 study. -

How to Read a Folktale: the 'Ibonia' Epic from Madagascar

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/109 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. A Merina performer of the highlands. Photo by Lee Haring (1975). World Oral Literature Series: Volume 4 How to Read a Folktale: The Ibonia Epic from Madagascar Translation and Reader’s Guide by Lee Haring http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Lee Haring; Foreword © 2013 Mark Turin This book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license (CC-BY 3.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work. The work must be attributed to the respective authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Lee Haring, How to Read a Folktale: The Ibonia Epic from Madagascar. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2013. DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0034 Further copyright and licensing details are available at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254053 This is the fourth volume in the World Oral Literature Series, published in association with the World Oral Literature Project. World Oral Literature Series: ISSN: 2050-7933 As with all Open Book Publishers titles, digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254053 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-06-0 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-05-3 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-909254-07-7 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-08-4 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-09-1 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0034 Cover image: Couple (Hazomanga?), sculpture in wood and pigment. -

Madagascar Epr Atlas Madagascar 1030

epr atlas 1029 Madagascar epr atlas madagascar 1030 Ethnicity in Madagascar Group selection Experts are divided on weather Madagascar should be considered an ethnically homogenous or heterogeneous country. Those arguing that Madagascar is homogenous consider all indigenous residents as Malagasy, since they all share mixed Southeast Asian and African ancestry, all speak dialects of the Malagasy language and many share common costumes with regard to dress, religion, social organization and other matters. For those that see Madagascar as an ethnically heterogeneous country suggest that there are as many as 20 different ethnic groups that view themselves as distinct social groups. The five most populous groups are the following. The largest of these 20 groups are the Merina (about 27% of the population). While their original homeland is the central highlands, the spread of the Me- rina Kingdom from 1810 until 1895 has left Merina people employed in many occupations across Madagascar. The second largest group is the Betsimisaraka (about 15% of the population), which live on the east cost and are mainly farmers. The third largest group is the Betsileo (about 13% of the population), which live in the southern central highlands. The fourth largest group is the Sakalava (about 5%), which live in the west and herd cattle. Finally, the fifth largest group is the Tandroy (about 8%), which live in the south of the is- land. As we will see below, those groups by themselves do play a dominant political role. Rather a twofold socially constructed com- bination of groups (the highlanders and costal people) is politically salient (2562; 2563, 121-129; 2564, 146-147; 2565) The political history 2562 [Metz, 1994] of Madagascar since independence from France in 1960 can roughly 2563 [Allen, 1995] 2564 be categorized in three periods. -

Reclaiming Islandness Through Cloth Circulation in Madagascar

Island Studies Journal, 13(2), 2018, 25-38 Reclaiming islandness through cloth circulation in Madagascar Hélène B. Ducros [email protected] ABSTRACT: Perceived as neither Asian nor completely African, often also neglected by island studies, Madagascar long remained the preserve of Francophone scholarship, absent from Anglo- American historical accounts of an Indian Ocean world. This paper examines the place of Madagascar in the literature at the intersection between Indian Ocean studies and textile studies to argue for its relevance in island studies. While decades of historical research have struggled to create a space for the island state and have not made its ‘islandness’ relevant, the paper shows that scholarship focused on Malagasy cloth has successfully re-placed the ‘Great Island’ in an Indian Ocean world and the larger global order, also making it easier to integrate it into a field of island studies that evolved to lend more attention to spatial and relational forces. Keywords: cloth, Indian Ocean world, islandness, islands, Madagascar, textile https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.69 © 2018 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. Introduction ‘La Grande Île’ (the Great Island), Madagascar, is a massive, elongated block (590,000 km²) lying in the most southern waters of the Indian Ocean―part of an area sometimes dubbed its “southern complex” (Campbell, 1989)―between the 12th and 24th parallels south, far from the ocean’s fulcrum. At its centre, north-south mountainous highlands with peaks over 2,500 m dominate its narrow littoral, facing 6,000 km of ocean to its east to reach Indonesia and 400 km to reach Africa to its west at the Mozambique Channel’s narrowest point.