The Matitanana Archaeological Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar Is Recruiting for the Following Position

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar is recruiting for the following position: TEMPORARY LANGUAGE AND CROSS-CULTURAL FACILITATORS (LCF) The position is based at the Peace Corps Training Center, in Mantasoa, and is a short-term contract (typically 10 to 14 weeks). The primary role of the LCF is to train American trainees and volunteers in the Malagasy language and culture. Training usually take place at a residential training facilities where both LCFs and trainees/volunteers stay full-time. LCFs work under the direct supervision of Peace Corps Madagascar’s Language Coordinator. The duties of the LCF include, but are not limited to: Conduct Malagasy language training classes with small groups of American trainees or volunteers. Participate in the preparation of language training materials or resources. Conduct formal sessions and provide ongoing informal instruction and advice to trainees/volunteers regarding cultural adaptation and culturally appropriate behavior Interact with trainees outside of the classroom setting, providing informal training during meals, social events and other periods outside of classroom training Actively participate in staff language training Serve as the cultural model and guide for trainees/volunteers within their communities Establish and maintain a healthy, productive team spirit among the language staff and between support staff and Volunteer trainers Occasionally serve as Malagasy and English interpreters and/or translators. As requested, install the new Volunteers at their permanent sites; and train their community-based tutor as needed Required Qualifications: Completion of secondary school (Minimum BACC) Fluency in English, French and Malagasy Mastery in at least one of the following dialects: Betsileo, Antakarana, Antambahoaka, Antemoro, Antesaka, Antefasy, Sakalava boina, Antanosy, Antandroy, Sihanaka, Mahafaly, Bara. -

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic Versus Emblematic Criteria

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic versus Emblematic Criteria Alexander Adelaar UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE This paper gives an overview of the literature on Malagasy dialect variety and the various Malagasy dialect classifications that have been proposed. It rejects the often held view that the way Malagasy dialects reflect the Proto- Austronesian phoneme sequences *li and *ti is a basic criterion for their genetic division. While the linguistic innovations shown in, respectively, central dialects (Merina, Betsileo, Sihanaka, Tanala) and southwestern dia- lects (Vezo, Mahafaly, Tandroy) clearly show that these groups form separate historical divisions, the linguistic developments in other (northern, eastern, and western) dialects are more difficult to interpret. The differences between Malagasy dialects are generally rather contained and do not seem to be the result of separate migration waves or the arrival of linguistically different migrant groups. The paper ends with a list of subgrouping criteria that will be useful for future research into the history of Malagasy dialects. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 This paper investigates some of the early linguistic changes that have contributed to the dialect diversity of Malagasy, as well as the various classifications that have been proposed for Malagasy dialects. Malagasy is an Austronesian language directly related to some of the languages spoken in Central Kalimantan Province and South Kalimantan Province in Indonesian Borneo. Together with these languages, it forms the South East Barito (henceforth SEB) subgroup, which belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. A historical classification of dialects or languages should be based in the first place on the oldest linguistic changes that have happened in the dialect or language group in ques- tion. -

Rano HP Et Ranon'ala

EVALUATION OF THE USAID/MADAGASCAR WATER SUPPLY, SANITATION AND HYGIENE BILATERAL PROJECTS: RANO HP ET RANON’ALA September 2014 This publication was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared independently by CAETIC Développement ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge Jean-Claude RANDRIANARISOA, COR, for his constant guidance during this whole assignment. Discussions and exchanges we had with him were always fruitful and encouraging and of a high technical level. This document could not have reached this level of quality without the invaluable inputs from Jacky Ralaiarivony and from USAID Madagascar Program Office staff, namely Vololontsoa Raharimalala. The authors: Balsama ANDRIANTSEHENO Jean Marie RAKOTOVAO Ramy RAZAFINDRALAMBO Jean Herivelo RAKOTONDRAINIBE FINAL EVALUATION OF USAID/MADAGASCAR WSSH PROJECTS: EVALUATION OF THE USAID/MADAGASCAR WATER SUPPLY, SANITATION AND HYGIENE BILATERAL PROJECTS: RANO HP ET RANON’ALA SEPTEMBER 9, 2014 CONTRACT N° AID-687-C-13-00004 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS ...................................................................................................................................................................... 1 LIST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................... -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

Candidats Fenerive Est Ambatoharanana 1

NOMBRE DISTRICT COMMUNE ENTITE NOM ET PRENOM(S) CANDIDATS CANDIDATS GROUPEMENT DE P.P MMM (Malagasy Miara FENERIVE EST AMBATOHARANANA 1 KOMPA Justin Miainga) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST AMBATOHARANANA 1 RAVELOSAONA Rasolo Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) GROUPEMENT DE P.P MMM (Malagasy Miara FENERIVE EST AMBODIMANGA II 1 SABOTSY Patrice Miainga) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST AMBODIMANGA II 1 RAZAFINDRAFARA Elyse Emmanuel Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) FENERIVE EST AMBODIMANGA II 1 INDEPENDANT TELO ADRIEN (Telo Adrien) TELO Adrien AMPASIMBE INDEPENDANT BOTOFASINA ANDRE (Botofasina FENERIVE EST 1 BOTOFASINA Andre MANANTSANTRANA Andre) AMPASIMBE GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST 1 VELONORO Gilbert MANANTSANTRANA Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) AMPASIMBE FENERIVE EST 1 GROUPEMENT DE P.P MTS (Malagasy Tonga Saina) ROBIA Maurille MANANTSANTRANA AMPASIMBE INDEPENDANT KOESAKA ROMAIN (Koesaka FENERIVE EST 1 KOESAKA Romain MANANTSANTRANA Romain) AMPASIMBE INDEPENDANT TALEVANA LAURENT GERVAIS FENERIVE EST 1 TALEVANA Laurent Gervais MANANTSANTRANA (Talevana Laurent Gervais) GROUPEMENT DE P.P MMM (Malagasy Miara FENERIVE EST AMPASINA MANINGORY 1 RABEFIARIVO Sabotsy Miainga) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST AMPASINA MANINGORY 1 CLOTAIRE Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) INDEPENDANT ROBERT MARCELIN (Robert FENERIVE EST ANTSIATSIAKA 1 ROBERT Marcelin Marcelin) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST ANTSIATSIAKA 1 KOANY Arthur Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) -

ETUDES DU PROJET D'amenagement HYDROAGRICOLE DU PERIMETRE IRRIGUE D’ANOSIVELO CR Anosivelo District Farafangana-Région Atsimo Atsinanana- Province De Fianarantsoa

UNIVERSITE D’ANTANANARIVO ------------------------------------ ECOLE SUPERIEURE POLYTECHNIQUE D’ANTANANARIVO ----------------------------------- DEPARTEMENT HYDRAULIQUE Mémoire de fin d’études en vue de l’obtention du diplôme d’Ingénieur ETUDES DU PROJET D’AMENAGEMENT HYDROAGRICOLE DU PERIMETRE IRRIGUE D’ANOSIVELO CR Anosivelo district Farafangana-Région Atsimo Atsinanana- Province Autonome de Fianarantsoa PRESENTE PAR : RAJAROELA Miandrisoa Date de soutenance : 06 Avril 2006 - Promotion 2005 - UNIVERSITE D’ANTANANARIVO ------------------------------------ ECOLE SUPERIEURE POLYTECHNIQUE D’ANTANANARIVO ----------------------------------- DEPARTEMENT HYDRAULIQUE Mémoire de fin d’étude en vue de l’obtention du diplôme d’Ingénieur ETUDES DU PROJET D’AMENAGEMENT HYDROAGRICOLE DU PERIMETRE IRRIGE D’ANOSIVELO CR Anosivelo district Farafangana-Région Atsimo Atsinanana-Province de Fianarantsoa Présenté par : RAJAROELA Miandrisoa Soutenu devant les membres de jury composés de : Président : Monsieur RAMANARIVO Solofomampionona, Chef du Département Hydraulique et Enseignant chercheur à l’ESPA Rapporteur : Monsieur RASOLOFONIAINA Jean Donné, Directeur du Centre National d’Etudes et d’Applications du Génie Rural (CNEAGR) Examinateurs : Monsieur RAKOTO DAVID Rambinintsoa Séraphin, Enseignant chercheur à l’ESPA Madame RAKOTONIAINA Dolly, Enseignant chercheur à l’ESPA Monsieur RANDRIAMAHERISOA Alain, Enseignant chercheur à l’ESPA Date de soutenance : 06 Avril 2006 Promotion 2005 MEMOIRE DE FIN D’ETUDES Département Hydraulique RAJAROELA Miandrisoa Promotion -

Rep 2 out Public 2010 S Tlet Sur of Ma Urvey Rvey Adagas Repor Scar Rt

Evidence for Malaria Medicines Policy Outlet Survey Republic of Madagascar 2010 Survey Report MINSTERE DE LA SANTE PUBLIQUE www. ACTwatch.info Copyright © 2010 Population Services International (PSI). All rights reserved. Acknowledgements ACTwatch is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. This study was implemented by Population Services International (PSI). ACTwatch’s Advisory Committee: Mr. Suprotik Basu Advisor to the UN Secretary General's Special Envoy for Malaria Mr. Rik Bosman Supply Chain Expert, Former Senior Vice President, Unilever Ms. Renia Coghlan Global Access Associate Director, Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) Dr. Thom Eisele Assistant Professor, Tulane University Mr. Louis Da Gama Malaria Advocacy & Communications Director, Global Health Advocates Dr. Paul Lavani Executive Director, RaPID Pharmacovigilance Program Dr. Ramanan Senior Fellow, Resources for the Future Dr. Matthew Lynch Project Director, VOICES, Johns Hopkins University Centre for Dr. Bernard Nahlen Deputy Coordinator, President's Malaria Initiative (PMI) Dr. Jayesh M. Pandit Head, Pharmacovigilance Department, Pharmacy and Poisons Board‐Kenya Dr. Melanie Renshaw Advisor to the UN Secretary General's Special Envoy for Malaria Mr. Oliver Sabot Vice‐President, Vaccines Clinton Foundation Ms. Rima Shretta Senior Program Associate, Strengthening Pharmaceutical Systems Dr. Rick Steketee Science Director, Malaria Control and Evaluation Partnership in Africa Dr. Warren Stevens Health Economist Dr. Gladys Tetteh CDC Resident Advisor, President’s Malaria -

Small Hydro Resource Mapping in Madagascar

Public Disclosure Authorized Small Hydro Resource Mapping in Madagascar INCEPTION REPORT [ENGLISH VERSION] August 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized This report was prepared by SHER Ingénieurs-Conseils s.a. in association with Mhylab, under contract to The World Bank. It is one of several outputs from the small hydro Renewable Energy Resource Mapping and Geospatial Planning [Project ID: P145350]. This activity is funded and supported by the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP), a multi-donor trust fund administered by The World Bank, under a global initiative on Renewable Energy Resource Mapping. Further details on the initiative can be obtained from the ESMAP website. This document is an interim output from the above-mentioned project. Users are strongly advised to exercise caution when utilizing the information and data contained, as this has not been subject to full peer review. The final, validated, peer reviewed output from this project will be a Madagascar Small Hydro Atlas, which will be published once the project is completed. Copyright © 2014 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK Washington DC 20433 Telephone: +1-202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the consultants listed, and not of World Bank staff. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work and accept no responsibility for any consequence of their use. -

Madagascar Cyclone Enawo

Antalaha ! ! MA002_10 ! ! Mandritsara Tsaratanana Mahanoro ! Andilambe ! Manambolosy Vanono ! Sahavia ! Behota Vanono Vanono Antsirabe Fanorah!ana Centre Manambolosy Ambalaben'Ifasina ! Ampanafanana Ambinaniboka ! Antsirabato ! Mahalina ! ! ! Ambodisatrana I Andasibe I Ambodiampana Fahambahy Antsiatsiaka ! ! Antsirat!enina Tsaratanana! Lampibe Andapanampambo ! Ambodimanga Ankoetrika ! ! Ambodiampana ! ! Aniribe Ankoba Bealampona ! ! Fitana Mananara !Marotandrano ! ! Fitana Marovato Ambodimadiro ! Riamena Avaratra Soavinarivo ! MANANARA Saromaona ! ! ! ! Analalava ! Marotandr!ano Mahatsinjo Sahazono ! ! Ambodivoanio Ambohim!ahavelona Befoza Ambodisatrana ! Andilamboahangy Antsirakivolo Ambodifano ! ! ! ! ! Ambodirotra ! ! Ambohipierenana Amboditangena ! Ambohimahavelona Ambodivoanio ! Mahafinaritra Tsarahasina Imorona Ambodisatrana ! ! Ambodivoangibe Vodivohitra Ambatofitarafana Antsiraka ! ! ! Ambatambaky ! Antanetilava ! Antsirabe Ambalavary Mananara-Avaratra ! Seranambe ! ! ! Makadabo Ambohimena ! Vohibe Antanambe ! Antanambao!be ! ! Antenina Andaparatibe ! Antsiraka Ambodisatrana Antanananivo ! ! Imorona Antsiatsiaka ! Antanambaon'amberina Antanananivo Sandrakatsy ! Fasina ! Sandrakatsy Sahasoa ! Antambontsona ! Ambodivato Ambodimanga ! Tanibe ! Fahatrosy ! Ambodimangatelo ! Sahakondro ! ANTANAMBAON'AMBERINA Antevialabe Belalona ! ! ! Ambatoharanana ! Antanambe Antsahamaloto ! Ambodimapay ! ! Ampasina ! Sahavoay Andranombazaha ! ! Analambola Antanambe ! ! Ambatoharanana Sahasoa Antevialabe ! ! Antenina Ampatakamaroreny Antenina Antanetilava -

Le Developpement Economique De La Region Vatovavy Fitovinany

UNIVERSITE D’ANTANANARIVO Année Universitaire : 2006-2007 Faculté de Droit, d’Economie, de Second Cycle – Promotion Sortante Gestion et de Sociologie Option : DEVELOPPEMENT DEPARTEMENT ECONOMIE « Promotion ANDRAINA » Mémoire de fin de Cycle LE DEVELOPPEMENT ECONOMIQUE DE LA REGION VATOVAVY FITOVINANY Encadré par : Monsieur Gédéon RAJAONSON Présenté par : MANIRISOA RAZAFIMARINTSARA Firmin Date de soutenance : 14 Décembre 2007 REMERCIEMENTS Pour commencer, je tiens à exprimer toute ma reconnaissance à tous ceux qui ont contribué, de près ou de loin, à ma formation et à la réalisation de ce Grand Mémoire de fin d’études en Economie. J’adresse donc tout particulièrement mes vifs remerciement à : • DIEU TOUT PUISSANT • Mon encadreur Monsieur Gédéon RAJAONSON ; • Tous les enseignants et les Personnels administratifs du Département Economie de la Faculté DEGS de l’Université d’Antananarivo ; • Monsieur Le Chef de Région de Vatovavy Fitovinany et ses équipes • Monsieur le Directeur Régional des Travaux Publics de Vatovavy Fitovinany • Ma famille pour leurs soutiens permanents. Veuillez accepter le témoignage de ma profonde gratitude. LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ANGAP : Agence Nationale de la Gestion des Aires Protégés CEG : Collège d’Enseignement Général CHD 1 : Centre Hospitalier de District Niveau 1 CHD 2 : Centre Hospitalier de District Niveau 2 CISCO : Circonscription Scolaire CSB 1 : Centre de Santé de Base Niveau 1 CSB 2 : Centre de Santé de Base Niveau 2 DRDR : Direction Régionale du Développement Rural EPP : Ecole Primaire Public FCE : Fianarantsoa Côte Est FER : Fonds d’Entretien Routier FTM : Foibe Toantsritanin’i Madagasikara GU : Guichet Unique HIMO : Haute Intensité de Main d’œuvre INSTAT : Institut National de la Statistique M.A.E.P. -

Evolution De La Couverture De Forets Naturelles a Madagascar

EVOLUTION DE LA COUVERTURE DE FORETS NATURELLES A MADAGASCAR 1990-2000-2005 mars 2009 La publication de ce document a été rendue possible grâce à un support financier du Peuple Americain à travers l’USAID (United States Agency for International Development). L’analyse de la déforestation pour les années 1990 et 2000 a été fournie par Conservation International. MINISTERE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT, DES FORETS ET DU TOURISME Le présent document est un rapport du Ministère de l’Environnement, des Forêts et du Tourisme (MEFT) sur l’état de de l’évolution de la couverture forestière naturelle à Madagascar entre 1990, 2000, et 2005. Ce rapport a été préparé par Conservation International. Par ailleurs, les personnes suivantes (par ordre alphabétique) ont apporté leur aimable contribution pour sa rédaction: Andrew Keck, James MacKinnon, Norotiana Mananjean, Sahondra Rajoelina, Pierrot Rakotoniaina, Solofo Ralaimihoatra, Bruno Ramamonjisoa, Balisama Ramaroson, Andoniaina Rambeloson, Rija Ranaivosoa, Pierre Randriamantsoa, Andriambolantsoa Rasolohery, Minoniaina L. Razafindramanga et Marc Steininger. Le traitement des imageries satellitaires a été réalisé par Balisama Ramaroson, Minoniaina L. Razafindramanga, Pierre Randriamantsoa et Rija Ranaivosoa et les cartes ont été réalisées par Andriambolantsoa Rasolohery. La réalisation de ce travail a été rendu possible grâce a une aide financière de l’United States Agency for International Development (USAID) et mobilisé à travers le projet JariAla. En effet, ce projet géré par International Resources Group (IRG) fournit des appuis stratégiques et techniques au MEFT dans la gestion du secteur forestier. Ce rapport devra être cité comme : MEFT, USAID et CI, 2009. Evolution de la couverture de forêts naturelles à Madagascar, 1990- 2000-2005. -

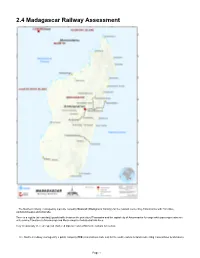

2.4 Madagascar Railway Assessment

2.4 Madagascar Railway Assessment - The Northern railway, managed by a private company Madarail (Madagascar Railway) for the network connecting Antananarivo with Tamatave, Ambatondrazaka and Antsirabe. There is a regular (at least daily) goods traffic between the port city of Toamasina and the capital city of Antananarivo for cargo while passenger trains are only serving Tamatave to Moramanga and Moramanga to Ambatrodrazaka lines. Very occasionally there are special chartered trips on restored Micheline railcars for tourists. - The Southern railway, managed by a public company FCE (Fianarantsoa Cote Est) for the south eastern network connecting Fianarantsoa to Manakara. Page 1 The southern line has regular passenger and cargo trains, which provides a slow but picturesque alternative to the recently rehabilitated road in the region. For more information on railway company contact details, please see the following link: Madagascar Railway Assessment Railway Companies and Consortia 4.2.7 Madagascar Railway Company Contact List Northern railway*: *During our study, Madarail was in the midst of restructuring, therefore, they did not want to share information, statistics or even contacts. All the information gathered and shared in this document comes exclusively from third parties or from data found on the internet. Madarail, was founded on October 10, 2002 following the decision of the Malagasy State to privatize the Malagasy National Railway Network1 (RNCFM). A concession agreement for the management of the North network is then established between the new private operator and the State. Madarail began operating the Northern railway network in Madagascar on 1 July 2003. In 2008, the Belgian operator Vecturis, already active in eight other African countries, became the majority shareholder of the company and the new railway operator.