The Origins of the Malagasy People, Some Certainties and a Few Mysteries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Accent and Intonation in a Malagasy Dialect. Raoniarisoa, Noro

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Accent and intonation in a Malagasy dialect. Raoniarisoa, Noro Award date: 1990 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 ACCENT AND INTONATION IN A MALAGASY DIALECT A Thesis submitted to the University of Wales by Noro RAONIARISOA in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of English and Linguistics University College of North Wales Bangor 1990 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to Dr. F. Gooding, my supervisor, for his valuable criticism and encouragement, and to his wife, Judy, for her kindness. My thanks are also due to the members of the Linguistics staff at the School of English and Linguistics in Bangor who, in one way or another, helped me at different stages of my research. The Malagasy Lutheran Church and the Norwegian Missionary Society have provided the financial support which has enabled me to do this research and I express my sincere gratitude to them. -

The Linguistic Background to SE Asian Sea Nomadism

The linguistic background to SE Asian sea nomadism Chapter in: Sea nomads of SE Asia past and present. Bérénice Bellina, Roger M. Blench & Jean-Christophe Galipaud eds. Singapore: NUS Press. Roger Blench McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Department of History, University of Jos Correspondence to: 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: Cambridge, March 21, 2017 Roger Blench Linguistic context of SE Asian sea peoples Submission version TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. The broad picture 3 3. The Samalic [Bajau] languages 4 4. The Orang Laut languages 5 5. The Andaman Sea languages 6 6. The Vezo hypothesis 9 7. Should we include river nomads? 10 8. Boat-people along the coast of China 10 9. Historical interpretation 11 References 13 TABLES Table 1. Linguistic affiliation of sea nomad populations 3 Table 2. Sailfish in Moklen/Moken 7 Table 3. Big-eye scad in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 4. Lake → ocean in Moklen 8 Table 5. Gill-net in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 6. Hearth on boat in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 7. Fishtrap in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 8. ‘Bracelet’ in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 9. Vezo fish names and their corresponding Malayopolynesian etymologies 9 FIGURES Figure 1. The Samalic languages 5 Figure 2. Schematic model of trade mosaic in the trans-Isthmian region 12 PHOTOS Photo 1. Orang Laut settlement in Riau 5 Photo 2. -

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar Is Recruiting for the Following Position

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar is recruiting for the following position: TEMPORARY LANGUAGE AND CROSS-CULTURAL FACILITATORS (LCF) The position is based at the Peace Corps Training Center, in Mantasoa, and is a short-term contract (typically 10 to 14 weeks). The primary role of the LCF is to train American trainees and volunteers in the Malagasy language and culture. Training usually take place at a residential training facilities where both LCFs and trainees/volunteers stay full-time. LCFs work under the direct supervision of Peace Corps Madagascar’s Language Coordinator. The duties of the LCF include, but are not limited to: Conduct Malagasy language training classes with small groups of American trainees or volunteers. Participate in the preparation of language training materials or resources. Conduct formal sessions and provide ongoing informal instruction and advice to trainees/volunteers regarding cultural adaptation and culturally appropriate behavior Interact with trainees outside of the classroom setting, providing informal training during meals, social events and other periods outside of classroom training Actively participate in staff language training Serve as the cultural model and guide for trainees/volunteers within their communities Establish and maintain a healthy, productive team spirit among the language staff and between support staff and Volunteer trainers Occasionally serve as Malagasy and English interpreters and/or translators. As requested, install the new Volunteers at their permanent sites; and train their community-based tutor as needed Required Qualifications: Completion of secondary school (Minimum BACC) Fluency in English, French and Malagasy Mastery in at least one of the following dialects: Betsileo, Antakarana, Antambahoaka, Antemoro, Antesaka, Antefasy, Sakalava boina, Antanosy, Antandroy, Sihanaka, Mahafaly, Bara. -

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic Versus Emblematic Criteria

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic versus Emblematic Criteria Alexander Adelaar UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE This paper gives an overview of the literature on Malagasy dialect variety and the various Malagasy dialect classifications that have been proposed. It rejects the often held view that the way Malagasy dialects reflect the Proto- Austronesian phoneme sequences *li and *ti is a basic criterion for their genetic division. While the linguistic innovations shown in, respectively, central dialects (Merina, Betsileo, Sihanaka, Tanala) and southwestern dia- lects (Vezo, Mahafaly, Tandroy) clearly show that these groups form separate historical divisions, the linguistic developments in other (northern, eastern, and western) dialects are more difficult to interpret. The differences between Malagasy dialects are generally rather contained and do not seem to be the result of separate migration waves or the arrival of linguistically different migrant groups. The paper ends with a list of subgrouping criteria that will be useful for future research into the history of Malagasy dialects. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 This paper investigates some of the early linguistic changes that have contributed to the dialect diversity of Malagasy, as well as the various classifications that have been proposed for Malagasy dialects. Malagasy is an Austronesian language directly related to some of the languages spoken in Central Kalimantan Province and South Kalimantan Province in Indonesian Borneo. Together with these languages, it forms the South East Barito (henceforth SEB) subgroup, which belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. A historical classification of dialects or languages should be based in the first place on the oldest linguistic changes that have happened in the dialect or language group in ques- tion. -

Evaluating the Effects of Colonialism on Deforestation in Madagascar: a Social and Environmental History

Evaluating the Effects of Colonialism on Deforestation in Madagascar: A Social and Environmental History Claudia Randrup Candidate for Honors in History Michael Fisher, Thesis Advisor Oberlin College Spring 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………… 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Methods and Historiography Chapter 1: Deforestation as an Environmental Issue.……………………………………… 20 The Geography of Madagascar Early Human Settlement Deforestation Chapter 2: Madagascar: The French Colony, the Forested Island…………………………. 28 Pre-Colonial Imperial History Becoming a French Colony Elements of a Colonial State Chapter 3: Appropriation and Exclusion…………………………………………………... 38 Resource Appropriation via Commercial Agriculture and Logging Concessions Rhetoric and Restriction: Madagascar’s First Protected Areas Chapter 4: Attitudes and Approaches to Forest Resources and Conservation…………….. 50 Tensions Mounting: Political Unrest Post-Colonial History and Environmental Trends Chapter 5: A New Era in Conservation?…………………………………………………... 59 The Legacy of Colonialism Cultural Conservation: The Case of Analafaly Looking Forward: Policy Recommendations Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………. 67 Selected Bibliography……………………………………………………………………… 69 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper was made possible by a number of individuals and institutions. An Artz grant and a Jerome Davis grant through Oberlin College’s History department and a Doris Baron Student Research Fund award through the Environmental Studies department supported -

Interdisciplinary Approaches to Stratifying the Peopling of Madagascar

INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACHES TO STRATIFYING THE PEOPLING OF MADAGASCAR Paper submitted for the proceedings of the Indian Ocean Conference, Madison, Wisconsin 23-24th October, 2015 Roger Blench McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Correspondence to: 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This version: Makurdi, 1 April, 2016 1 Malagasy - Sulawesi lexical connections Roger Blench Submission version TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................................. i ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................................ii 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Models for the settlement of Madagascar ................................................................................................. 2 3. Linguistic evidence...................................................................................................................................... 2 3.1 Overview 2 3.2 Connections with Sulawesi languages 3 3.2.1 Nouns.............................................................................................................................................. -

1646 KMS Kenya Past and Present Issue 46.Pdf

Kenya Past and Present ISSUE 46, 2019 CONTENTS KMS HIGHLIGHTS, 2018 3 Pat Jentz NMK HIGHLIGHTS, 2018 7 Juliana Jebet NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS 13 AT MT. ELGON CAVES, WESTERN KENYA Emmanuel K. Ndiema, Purity Kiura, Rahab Kinyanjui RAS SERANI: AN HISTORICAL COMPLEX 22 Hans-Martin Sommer COCKATOOS AND CROCODILES: 32 SEARCHING FOR WORDS OF AUSTRONESIAN ORIGIN IN SWAHILI Martin Walsh PURI, PAROTHA, PICKLES AND PAPADAM 41 Saryoo Shah ZANZIBAR PLATES: MAASTRICHT AND OTHER PLATES 45 ON THE EAST AFRICAN COAST Villoo Nowrojee and Pheroze Nowrojee EXCEPTIONAL OBJECTS FROM KENYA’S 53 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES Angela W. Kabiru FRONT COVER ‘They speak to us of warm welcomes and traditional hospitality, of large offerings of richly flavoured rice, of meat cooked in coconut milk, of sweets as generous in quantity as the meals they followed.’ See Villoo and Pheroze Nowrojee. ‘Zanzibar Plates’ p. 45 1 KMS COUNCIL 2018 - 2019 KENYA MUSEUM SOCIETY Officers The Kenya Museum Society (KMS) is a non-profit Chairperson Pat Jentz members’ organisation formed in 1971 to support Vice Chairperson Jill Ghai and promote the work of the National Museums of Honorary Secretary Dr Marla Stone Kenya (NMK). You are invited to join the Society and Honorary Treasurer Peter Brice receive Kenya Past and Present. Privileges to members include regular newsletters, free entrance to all Council Members national museums, prehistoric sites and monuments PR and Marketing Coordinator Kari Mutu under the jurisdiction of the National Museums of Weekend Outings Coordinator Narinder Heyer Kenya, entry to the Oloolua Nature Trail at half price Day Outings Coordinator Catalina Osorio and 5% discount on books in the KMS shop. -

'The Vezo Are Not a Kind of People'. Identity, Difference and 'Ethnicity' Among a Fishing People of Western Madagascar

LSE Research Online Article (refereed) Rita Astuti 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar Originally published in American ethnologist, 22 (3). pp. 464-482 © 1995 by the Regents of the University of California on behalf of the American Ethnological Society. You may cite this version as: Astuti, Rita (1995). 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar [online]. London: LSE Research Online. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/archive/00000470 Available online: November 2005 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the publisher’s version remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk Contact LSE Research Online at: [email protected] 1 `THE VEZO ARE NOT A KIND OF PEOPLE' IDENTITY, DIFFERENCE AND `ETHNICITY' AMONG A FISHING PEOPLE OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR Rita Astuti London School of Economics Acknowledgments Fieldwork was conducted in two Vezo villages, Betania and Belo-sur Mer, between November 1987 and June 1989. -

Expanded PDF Profile

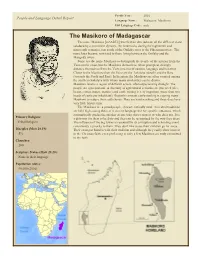

Profile Year: 2001 People and Language Detail Report Language Name: Malagasy, Masikoro ISO Language Code: msh The Masikoro of Madagascar The name Masikoro [mASikUr] was first used to indicate all the different clans subdued by a prominent dynasty, the Andrevola, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, just south of the Onilahy river to the Fiherenana river. The name later became restricted to those living between the Onilahy and the Mangoky rivers. Some use the name Masikoro to distinguish the people of the interior from the Vezo on the coast, but the Masikoro themselves, when prompted, strongly distance themselves from the Vezo in terms of custom, language and behavior. Closer to the Masikoro than the Vezo are the Tañalaña (South) and the Bara (towards the North and East). In literature the Masikoro are often counted among the southern Sakalava with whom many similarities can be drawn. Masikoro land is a region of difficult access, often experiencing drought. The people are agro-pastoral. A diversity of agricultural activities are practiced (rice, beans, cotton, maize, manioc) and cattle raising is very important (more than two heads of cattle per inhabitant). Recently rampant cattle-rustling is causing many Masikoro to reduce their cattle herds. They are hard-working and these days have very little leisure time. The Masikoro are a proud people, characteristically rural. Ancestral traditions are held high among them as is correct language use for specific situations, which automatically grades the speaker as one who shows respect or who does not. It is Primary Religion: a dishonor for them to be dirty and they can be recognized by the way they dress. -

Lesson 2 the People of Madagascar

LUTHERAN HOUR MINISTRIES online mission trip Curriculum LESSON 2 THE PEOPLE OF MADAGASCAR 660 MASON RIDGE CENTER DRIVE, SAINT LOUIS, MO 63141 | LHM.ORG 0117 LHM – MADAGASCAR Lesson 2 – The People of Madagascar Population On the map, Madagascar is very close to the eastern edge of Africa. This closeness would lead people to conclude that the inhabitants of Madagascar are predominately African. This is not true. The native inhabitants of Madagascar are the Malagasy (pronounced mah-lah-GAH-shee), who originated in Malaysia and Indonesia and reached Madagascar about 1,500 years ago. The language, customs, and physical appearance of today’s Malagasy reflect their Asian ancestry. Nearly 22.5 million people live in modern Madagascar. The annual growth rate of three percent combined with an average life expectancy of only sixty- four years gives Madagascar a young population. About sixty percent of the Malagasy people are less than twenty-five years old. Thirty-five percent of the adult population is classified as illiterate. More than ninety-five percent of the population is of Malagasy origin. The other five percent is made up of French, Comorians, Indo-Pakistanis, and Chinese peoples. The Malagasy are divided into 20 distinct ethnic groups, each of which occupies a certain area of the island. These groups originally started as loosely organized clans. Each clan remained apart from each other clan, marrying only within its clan. The clans developed into separate ethnic groups. Today there is an increased amount of intermarriage between the clans blurring the lines of distinction. All groups consider themselves as equally Malagasy. -

A Strategy to Reach Animistic People in Madagascar

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2006 A Strategy To Reach Animistic People in Madagascar Jacques Ratsimbason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Ratsimbason, Jacques, "A Strategy To Reach Animistic People in Madagascar" (2006). Dissertation Projects DMin. 690. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/690 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A STRATEGY TO REACH ANIMISTIC PEOPLE IN MADAGASCAR by Jacques Ratsimbason Adviser: Bruce Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A STRATEGY TO REACH ANIMISTIC PEOPLE IN MADAGASCAR Name of researcher: Jacques Ratsimbason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Bruce Bauer, D.Miss. Date completed: August 2006 Problem The majority of the Malagasy people who live in Madagascar are unreached with the gospel message. A preliminary investigation of current literature indicated that 50 percent of the Malagasy are followers of traditional religions. This present study was to develop a strategy to reach the animistic people with the gospel message. Method This study presents Malagasy people, their social characteristics, population, worldviews, and lifestyles. A study;and evaluation of Malagasy beliefs and practices were developed using Hiebert's model of critical contextualization. Results The study reveals that the Seventh-day Adventist Church must update its evangelistic methods to reach animistic people and finish the gospel commission in Madagascar. -

Fombandrazana Vezo: Ethnic Identity and Subsistence

FOMBANDRAZANA VEZO: ETHNIC IDENTITY AND SUBSISTENCE STRATEGIES AMONG COASTAL FISHERS OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR by EARL FURMAN SANDERS (Under the Direction of THEODORE GRAGSON) ABSTRACT The complex dynamic among coastal peoples of western Madagascar involves spread of cultural elements due to extensive seasonal migrations, tribes and ethnic groups merging into progressively broader ethnic groups, distinctions based on interethnic and intra-ethnic boundaries, and lumping of peoples with remotely similar subsistence patterns which has perpetuated ethnonym vagaries. This study analyzes the cultural bases of the Vezo, a group of marine fishers inhabiting the west coast of Madagascar, with the intent of presenting a clearer image of what is entailed within the ethnonym, Vezo, both with respect to subsistence strategies and cultural identity. Three broad areas of inquiry, ethnohistory, ecological niche as understood from the Eltonian definition, and geographical scope inform the field research. Access to these areas leans heavily on oral histories, which in turn is greatly facilitated by intensive participant observation and work in the native language. The analysis shows that the Vezo constitute a distinct ethnic group composed of diverse named patrilineal descent groups. This ethnic group is defined by common origins and a shared sense of common history, which along with the origins of the taboos are maintained within their oral histories. Within the ethnonym, Vezo, there are subsistence as well as other cultural distinctions, most notably the taboos. These distinctions are the bases of the ethnic boundaries separating those who belong to the Vezo cultural group and others who are referred to as Vezo (Vezom-potake and Vezo-loatse) due to geographical disposition.