Ea71232020revised May2019b

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport Final De La Composante 2

ANALYSE DE LA DÉFORESTATION ET DE SES AGENTS, CAUSES ET FACTEURS SOUS-JACENTS Rapport final de la composante 2 : Analyse des agents, causes et facteurs de la déforestation et réalisation de projections des futurs taux de déforestation sous différents scénarios Juin 2016 Liste des acronymes AA Atsimo Andrefana ABS Agriculture sur abattis-brûlis AGR Activités Génératrices de Revenus AP Aire Protégée BDD Base De Données CLP Comité Local du Parc DREEF Direction Régionale de l’Environnement, Écologie et des Forêts FKT Fokontany JSDF Japanese Social for Development Fund PCD Plan Communal de Développement PFNL Produits forestiers non ligneux PIC Pôles Intégrés de Croissance PSDR Projet de Soutien au Développement Rural MNP Madagascar National Parc WCS Wildlife Conservation Society WWF World Wildlife Fund ZE Zone d’Étude Analyse de la déforestation dans la zone du Parc National de Mikea, Rapport de la composante 2, juin 2016. 2 Sommaire Liste des cartes ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Liste des figures ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Liste des illustrations ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Liste des tableaux ................................................................................................................................................. -

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar Is Recruiting for the Following Position

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar is recruiting for the following position: TEMPORARY LANGUAGE AND CROSS-CULTURAL FACILITATORS (LCF) The position is based at the Peace Corps Training Center, in Mantasoa, and is a short-term contract (typically 10 to 14 weeks). The primary role of the LCF is to train American trainees and volunteers in the Malagasy language and culture. Training usually take place at a residential training facilities where both LCFs and trainees/volunteers stay full-time. LCFs work under the direct supervision of Peace Corps Madagascar’s Language Coordinator. The duties of the LCF include, but are not limited to: Conduct Malagasy language training classes with small groups of American trainees or volunteers. Participate in the preparation of language training materials or resources. Conduct formal sessions and provide ongoing informal instruction and advice to trainees/volunteers regarding cultural adaptation and culturally appropriate behavior Interact with trainees outside of the classroom setting, providing informal training during meals, social events and other periods outside of classroom training Actively participate in staff language training Serve as the cultural model and guide for trainees/volunteers within their communities Establish and maintain a healthy, productive team spirit among the language staff and between support staff and Volunteer trainers Occasionally serve as Malagasy and English interpreters and/or translators. As requested, install the new Volunteers at their permanent sites; and train their community-based tutor as needed Required Qualifications: Completion of secondary school (Minimum BACC) Fluency in English, French and Malagasy Mastery in at least one of the following dialects: Betsileo, Antakarana, Antambahoaka, Antemoro, Antesaka, Antefasy, Sakalava boina, Antanosy, Antandroy, Sihanaka, Mahafaly, Bara. -

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic Versus Emblematic Criteria

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic versus Emblematic Criteria Alexander Adelaar UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE This paper gives an overview of the literature on Malagasy dialect variety and the various Malagasy dialect classifications that have been proposed. It rejects the often held view that the way Malagasy dialects reflect the Proto- Austronesian phoneme sequences *li and *ti is a basic criterion for their genetic division. While the linguistic innovations shown in, respectively, central dialects (Merina, Betsileo, Sihanaka, Tanala) and southwestern dia- lects (Vezo, Mahafaly, Tandroy) clearly show that these groups form separate historical divisions, the linguistic developments in other (northern, eastern, and western) dialects are more difficult to interpret. The differences between Malagasy dialects are generally rather contained and do not seem to be the result of separate migration waves or the arrival of linguistically different migrant groups. The paper ends with a list of subgrouping criteria that will be useful for future research into the history of Malagasy dialects. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 This paper investigates some of the early linguistic changes that have contributed to the dialect diversity of Malagasy, as well as the various classifications that have been proposed for Malagasy dialects. Malagasy is an Austronesian language directly related to some of the languages spoken in Central Kalimantan Province and South Kalimantan Province in Indonesian Borneo. Together with these languages, it forms the South East Barito (henceforth SEB) subgroup, which belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. A historical classification of dialects or languages should be based in the first place on the oldest linguistic changes that have happened in the dialect or language group in ques- tion. -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

Memoire Version Final

N° d’ordre : UNIVERSITE DE TOLIARA FACULTE DES SCIENCES Licence professionnelle en Biodiversité et Environnement L’EAU, RESSOURCES A PRESERVER DANS LA REGION DU SUD OUEST, CAS DES DISTRICTS DE TOLIARA I ET DE TOLIARA II Présenté par : ANDRIANARIVONY Jean Hervé Nelson Soutenu le : 03 Novembre 2010 Membres de Jury : Président : Professeur DINA Alphonse Examinateur : Monsieur RANDRIANILAINA Herimampionona Rapporteur : Professeur REJO-FIENENA Félicitée Rapporteur : Sœur VOLOLONIAINA Sahondra Marie Angeline Année Universitaire 2008 -2009 (3 e promotion) 34 REMERCIEMENTS Je tiens à exprimer mes vifs remerciements à : ■Monsieur le Professeur DINA Alphonse, Président de l’Université de Toliara, qui à voulu accepter la présidence du jury. ■Madame le Professeur REJO–FIENENA Félicitée, Responsable de l’UFR Biodiversité et Environnement. Formation Licence professionnelle pour son encadrement fructueux depuis le début de notre formation jusqu’à ce jour. ■Monsieur le Docteur LEZO Hugues, Doyen de la Faculté des Sciences de l’Université de Toliara qui ma donné l’autorisation de soutenir. ■Sœur VOLOLONIAINA Sahondra Marie Angeline ; Directrice de l’Institut PERE BARRE, qui s’est chargée de nous avec une remarquable gentillesse. Elle n’a jamais économisé ses peines pour la réalisation de tous les problèmes liés à nos études et a bien voulu assurer l’encadrement technique durant toute réalisation de ce travail, malgré ses nombreuses obligations. ■Monsieur RANDRIANILAINA Herimampionona : Hydrogéologue, Chargé de l’assainissement et de la Gestion Intégrée des Ressources en Eau à la Direction Régionale du Ministère de l’eau –ANTSIMO ANDREFANA pour avoir bien voulu accepter d’assurer le rôle d’examinateur dans le but d’apporter des améliorations à ce travail. -

UNICEF Madagascar Country Office Humanitarian Situation

ary Madagascar u Country Office Humanitarian Situation Report No. 1 Rakotomanga © UNICEF Madagascar/Jan © UNICEF 2020/ UNICEF/UN0267547/Raoelison Reporting Period: 01 January to 31 March 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers Between January 19, 2020 till January 23,2020, there was heavy rains in the northwestern part of Madagascar, more than twice the normal precipitation 1.1 million during the rainy season, resulting in floods in 13 districts. Children in need of humanitarian assistance Emergency response was initially undertaken using prepositioned stocks. Since February 27, the affected districts such as Amparafaravola, Ambatondrazaka, Mampikony, Marovoay. Mitsinjo, Soalalaand Ambato Boeny districts are supplied 2 million by a combination of land, and river transportation. People in need UNICEF Madagascar currently focuses on disaster risk reduction to build resilience, reaching vulnerable people in the drought-prone south suffering from malnutrition and lack of access to safe water in addition to reinforcing 337.200 government systems in preparation for a full-fledged nation-wide response to the Children to be reached COVID_19 Pandemic. From January to March 2020, 3542 children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) were admitted and treated,22 % percent of the 2020 target of 16 000 SAM 441.000 children accessing therapeutic treatment. of peo People to be reached A total of 60,910 people in the south gained access to safe water through water trucking and rehabilitation of boreholes. In preparation for Covid19 response: WASH Needs assessments have been carried out in Health centres and Airports, items have been pre-positioned at 9 entry points, Infection prevention communication through posters is ongoing, and programming for cash transfers to vulnerable households to support basic consumption and compensation for loss of revenues is underway. -

'The Vezo Are Not a Kind of People'. Identity, Difference and 'Ethnicity' Among a Fishing People of Western Madagascar

LSE Research Online Article (refereed) Rita Astuti 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar Originally published in American ethnologist, 22 (3). pp. 464-482 © 1995 by the Regents of the University of California on behalf of the American Ethnological Society. You may cite this version as: Astuti, Rita (1995). 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar [online]. London: LSE Research Online. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/archive/00000470 Available online: November 2005 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the publisher’s version remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk Contact LSE Research Online at: [email protected] 1 `THE VEZO ARE NOT A KIND OF PEOPLE' IDENTITY, DIFFERENCE AND `ETHNICITY' AMONG A FISHING PEOPLE OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR Rita Astuti London School of Economics Acknowledgments Fieldwork was conducted in two Vezo villages, Betania and Belo-sur Mer, between November 1987 and June 1989. -

The South West Madagascar Tortoise Survey Project End of Phase 2 Preliminary Report to Donors and Supporters

The South West Madagascar Tortoise Survey Project End of Phase 2 Preliminary Report to Donors and Supporters Southern Madagascar Tortoise Conservation Project Preliminary Donor Report –RCJ Walker 2010 The species documented within this report have suffered considerably at the hands of commercial reptile collectors in recent years. Due to the sensitive nature of some information detailing the precise locations of populations of tortoises contained within this report, the author asks that any public dissemination, of the locations of these rare animals be done with discretion. Cover photo: Pyxis arachnoides arachnoides; all photographs by Ryan Walker and Brain Horne Summary • This summary report documents phase two of the South West Madagascar Tortoise Survey Project (formally the Madagascar Spider Tortoise Conservation and Science Project). The project has redirected focus during this second phase, to concentrate research and survey effort for both of southern Madagascar’s threatened tortoise species; Pyxis arachnoides and Astrocheys radiata. • The aims and objectives of this three phase project, were developed during the 2008 Madagascar Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle IUCN/SSC Red Listing and Conservation Planning Meeting held in Antananarivo, Madagascar. • This project now has five research objectives: o Establish the population density and current range of the remaining populations of P. arachnoides and radiated tortoise A. radiata. o Assess the response of the spider tortoises to anthropogenic habitat disturbance and alteration. o Assess the extent of global internet based trade in Madagascar’s four endemic, Critically Endangered tortoise species. o Assess the poaching pressure placed on radiated tortoises for the local tortoise meat trade. o Carry out genetic analysis on the three subspecies of spider tortoise and confirm that they are indeed three subspecies and at what geographical point one sub species population changes into another. -

Coelacanth Discoveries in Madagascar, with AUTHORS: Andrew Cooke1 Recommendations on Research and Conservation Michael N

Coelacanth discoveries in Madagascar, with AUTHORS: Andrew Cooke1 recommendations on research and conservation Michael N. Bruton2 Minosoa Ravololoharinjara3 The presence of populations of the Western Indian Ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) in AFFILIATIONS: 1Resolve sarl, Ivandry Business Madagascar is not surprising considering the vast range of habitats which the ancient island offers. Center, Antananarivo, Madagascar The discovery of a substantial population of coelacanths through handline fishing on the steep volcanic 2Honorary Research Associate, South African Institute for Aquatic slopes of Comoros archipelago initially provided an important source of museum specimens and was Biodiversity, Makhanda, South Africa the main focus of coelacanth research for almost 40 years. The advent of deep-set gillnets, or jarifa, for 3Resolve sarl, Ivandry Business catching sharks, driven by the demand for shark fins and oil from China in the mid- to late 1980s, resulted Center, Antananarivo, Madagascar in an explosion of coelacanth captures in Madagascar and other countries in the Western Indian Ocean. CORRESPONDENCE TO: We review coelacanth catches in Madagascar and present evidence for the existence of one or more Andrew Cooke populations of L. chalumnae distributed along about 1000 km of the southern and western coasts of the island. We also hypothesise that coelacanths are likely to occur around the whole continental margin EMAIL: [email protected] of Madagascar, making it the epicentre of coelacanth distribution in the Western Indian Ocean and the likely progenitor of the younger Comoros coelacanth population. Finally, we discuss the importance and DATES: vulnerability of the population of coelacanths inhabiting the submarine slopes of the Onilahy canyon in Received: 23 June 2020 Revised: 02 Oct. -

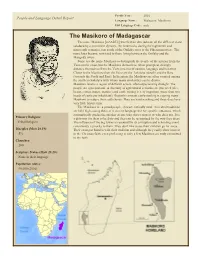

Expanded PDF Profile

Profile Year: 2001 People and Language Detail Report Language Name: Malagasy, Masikoro ISO Language Code: msh The Masikoro of Madagascar The name Masikoro [mASikUr] was first used to indicate all the different clans subdued by a prominent dynasty, the Andrevola, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, just south of the Onilahy river to the Fiherenana river. The name later became restricted to those living between the Onilahy and the Mangoky rivers. Some use the name Masikoro to distinguish the people of the interior from the Vezo on the coast, but the Masikoro themselves, when prompted, strongly distance themselves from the Vezo in terms of custom, language and behavior. Closer to the Masikoro than the Vezo are the Tañalaña (South) and the Bara (towards the North and East). In literature the Masikoro are often counted among the southern Sakalava with whom many similarities can be drawn. Masikoro land is a region of difficult access, often experiencing drought. The people are agro-pastoral. A diversity of agricultural activities are practiced (rice, beans, cotton, maize, manioc) and cattle raising is very important (more than two heads of cattle per inhabitant). Recently rampant cattle-rustling is causing many Masikoro to reduce their cattle herds. They are hard-working and these days have very little leisure time. The Masikoro are a proud people, characteristically rural. Ancestral traditions are held high among them as is correct language use for specific situations, which automatically grades the speaker as one who shows respect or who does not. It is Primary Religion: a dishonor for them to be dirty and they can be recognized by the way they dress. -

Bulletin De Situation Acridienne Madagascar

BULLETIN DE SITUATION ACRIDIENNE MADAGASCAR Bulletin de la première décade de juin 2014 (2014-D16) SOMMAIRE CELLULE DE VEILLE ACRIDIENNE Conditions éco-météorologiques : page 1 Situation acridienne : page 2 Situation antiacridienne : page 6 Annexes : page 10 CONDITIONS CONDITIONS ÉCO-MÉTÉOROLOGIQUES ECO-METEOROLOGIQUES DURANT DURANT LA LA PREMIÈRE DEUXIEME DÉCADE DECADE DEDE JUIN JANVIER 2014 2014 Durant la 1ère décade, la pluviosité était nulle à très faible et donc hyper-déficitaire par rapport aux besoins du Criquet migrateur malgache dans toute la Grande-Île (figure 1). Les relevés (CNA) effectués dans l’Aire grégarigène montraient cependant que la plage optimale pluviométrique (annexe 1) était atteinte dans certaines localités des compartiments Centre et Sud de l’Aire de densation (11,5 mm à Efoetse, 38,0 mm à Beloha et 28,0 mm à Lavanono). Dans les zones à faible pluviosité, à l’exception de l’Aire d’invasion Est, les réserves hydriques des sols devenaient de plus en plus difficilement utilisables, le point de flétrissement permanent pouvant être atteint dans les biotopes les plus arides. Les strates herbeuses dans les différentes régions naturelles se desséchaient rapidement. En général, la hauteur des strates herbeuses variait de 10 à 80 cm selon les régions naturelles, les biotopes et les espèces graminéennes. Le taux de verdissement variait de 20 à 40 % dans l’Aire grégarigène et de 30 à 50 % dans l’Aire d’invasion. Les biotopes favorables au développement des acridiens se limitaient progressivement aux bas-fonds. Dans l’Aire grégarigène, le vent était de secteur Est tandis que, dans l’Aire d’invasion, les vents dominants soufflaient du Sud-Est vers le Nord- Ouest. -

Evaluation Des Impacts Du Cyclone Haruna Sur Les Moyens De Subsistance

1 EVALUATION DES IMPACTS DU CYCLONE HARUNA SUR LES MOYENS DE SUBSISTANCE, ET SUR LA SECURITE ALIMENTAIRE ET LA VULNERABILITE DES POPULATONS AFFECTEES commune rurale de Sokobory, Tuléar Tuléar I Photo crédit : ACF Cluster Sécurité Alimentaire et Moyens de Subsistance Avril 2013 2 TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES CARTES..................................................................................................................................... 3 LISTE DES GRAPHIQUES ..................................................................................................................................... 3 LISTE DES TABLEAUX ........................................................................................................................................... 4 ACRONYMES ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 RESUME ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 1. CONTEXTE ............................................................................................................................................ 8 2. OBJECTIFS ET METHODES ............................................................................................................. 11 2.1 OBJECTIFS ........................................................................................................................................... 11 2.2 METHODOLOGIE