Formal Education and the Rural Dwelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar Is Recruiting for the Following Position

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar is recruiting for the following position: TEMPORARY LANGUAGE AND CROSS-CULTURAL FACILITATORS (LCF) The position is based at the Peace Corps Training Center, in Mantasoa, and is a short-term contract (typically 10 to 14 weeks). The primary role of the LCF is to train American trainees and volunteers in the Malagasy language and culture. Training usually take place at a residential training facilities where both LCFs and trainees/volunteers stay full-time. LCFs work under the direct supervision of Peace Corps Madagascar’s Language Coordinator. The duties of the LCF include, but are not limited to: Conduct Malagasy language training classes with small groups of American trainees or volunteers. Participate in the preparation of language training materials or resources. Conduct formal sessions and provide ongoing informal instruction and advice to trainees/volunteers regarding cultural adaptation and culturally appropriate behavior Interact with trainees outside of the classroom setting, providing informal training during meals, social events and other periods outside of classroom training Actively participate in staff language training Serve as the cultural model and guide for trainees/volunteers within their communities Establish and maintain a healthy, productive team spirit among the language staff and between support staff and Volunteer trainers Occasionally serve as Malagasy and English interpreters and/or translators. As requested, install the new Volunteers at their permanent sites; and train their community-based tutor as needed Required Qualifications: Completion of secondary school (Minimum BACC) Fluency in English, French and Malagasy Mastery in at least one of the following dialects: Betsileo, Antakarana, Antambahoaka, Antemoro, Antesaka, Antefasy, Sakalava boina, Antanosy, Antandroy, Sihanaka, Mahafaly, Bara. -

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic Versus Emblematic Criteria

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic versus Emblematic Criteria Alexander Adelaar UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE This paper gives an overview of the literature on Malagasy dialect variety and the various Malagasy dialect classifications that have been proposed. It rejects the often held view that the way Malagasy dialects reflect the Proto- Austronesian phoneme sequences *li and *ti is a basic criterion for their genetic division. While the linguistic innovations shown in, respectively, central dialects (Merina, Betsileo, Sihanaka, Tanala) and southwestern dia- lects (Vezo, Mahafaly, Tandroy) clearly show that these groups form separate historical divisions, the linguistic developments in other (northern, eastern, and western) dialects are more difficult to interpret. The differences between Malagasy dialects are generally rather contained and do not seem to be the result of separate migration waves or the arrival of linguistically different migrant groups. The paper ends with a list of subgrouping criteria that will be useful for future research into the history of Malagasy dialects. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 This paper investigates some of the early linguistic changes that have contributed to the dialect diversity of Malagasy, as well as the various classifications that have been proposed for Malagasy dialects. Malagasy is an Austronesian language directly related to some of the languages spoken in Central Kalimantan Province and South Kalimantan Province in Indonesian Borneo. Together with these languages, it forms the South East Barito (henceforth SEB) subgroup, which belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. A historical classification of dialects or languages should be based in the first place on the oldest linguistic changes that have happened in the dialect or language group in ques- tion. -

Possibilities and Challenges in Early Childhood Care and Education in Madagascar

Possibilities and Challenges in Early Childhood Care and Education in Madagascar Access and Parental Choice in preschools in Toliara Jiyean Park Faculty of Educational Science UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2014 II Possibilities and Challenges in Early Childhood Care and Education in Madagascar Access and Parental Choice in preschools in Toliara A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Comparative and International Education Faculty of Educational Science III © Jiyean Park 2014 The Possibilities and Challenges in Early Childhood Care and Education in Madagascar: Access and Parental Choice in preschools in Toliara http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract This study addresses access and parental choice in ECCE in Madagascar. The purpose of the study is to explore the value of ECCE and the factors obstructing access to ECCE, to examine the similarities and differences of the parental choice between public and private preschools in Madagascar and finally, to suggest the measures or strategies improving access to ECCE in the countries with low resource. Social exclusion, social class and school choice within rational action theory and Bourdieu’s cultural capital was used as a theoretical framework. Madagascar was chosen as the site of research since it offers an opportunity to explore the situation of access and parental choice in ECCE in a low-resource context and to investigate the impact of political and economic crisis on access to ECCE and parental choice. The study is designed by a comparative research. Key stakeholders the central and local government officials and a representative of an international organization and civil society, teachers and parents participated in this study. -

III. Tertiary Education in Madagascar: Review of Previous Studies

WORLD BANK Public Disclosure Authorized Tertiary education in Madagascar Public Disclosure Authorized A review of the Bologna process (LMD), its implementation in Madagascar, the status of recent World Bank analyses and recommendations, and suggestions for the immediate future Public Disclosure Authorized Richard SACK and Farasoa RAVALITERA Juin 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized i | P a g e Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 II. The Bologna Process and LMD implementation ..................................................................................... 2 Diploma structure ................................................................................................................................... 4 Academic credit units ............................................................................................................................. 4 National Qualifications Frameworks ...................................................................................................... 5 Quality assurance ................................................................................................................................... 6 Lessons from non-European countries.................................................................................................. -

'The Vezo Are Not a Kind of People'. Identity, Difference and 'Ethnicity' Among a Fishing People of Western Madagascar

LSE Research Online Article (refereed) Rita Astuti 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar Originally published in American ethnologist, 22 (3). pp. 464-482 © 1995 by the Regents of the University of California on behalf of the American Ethnological Society. You may cite this version as: Astuti, Rita (1995). 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar [online]. London: LSE Research Online. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/archive/00000470 Available online: November 2005 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the publisher’s version remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk Contact LSE Research Online at: [email protected] 1 `THE VEZO ARE NOT A KIND OF PEOPLE' IDENTITY, DIFFERENCE AND `ETHNICITY' AMONG A FISHING PEOPLE OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR Rita Astuti London School of Economics Acknowledgments Fieldwork was conducted in two Vezo villages, Betania and Belo-sur Mer, between November 1987 and June 1989. -

DOCUMENT RESUME the Development of Technical And

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 411 471 CE 074 838 TITLE The Development of Technical and Vocational Education in Africa. INSTITUTION United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Dakar (Senegal). Regional Office for Education in Africa. ISBN ISBN-92-9091-054-2 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 411p.; Product of the International Project on Technical and Vocational Education (UNEVOC). PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Case Studies; *Developing Nations; Economic Development; Education Work Relationship; Educational Cooperation; *Educational Development; Educational Legislation; *Educational Policy; Foreign Countries; Industry; *Role of Education; *School Business Relationship; *Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS *Africa ABSTRACT The 13 chapters in this book depict the challenges facing African nations in their efforts to develop their technical and vocational education (TVE) systems. Chapter 1,"TVE in Africa: A Synthesis of Case Studies" (B. Wanjala Kerre), presents a synthesis of the case studies in which the following major trends taking place within the existing socioeconomic context are discussed: TVE within existing educational structures; cooperation between TVE institutions and enterprises; major challenges facing the nations in their efforts to develop TVE; and the innovative measures undertaken in response to the problems and constraints experienced. The remaining 12 chapters are individual case studies giving a more detailed picture of natural efforts and challenges encountered in the development of TVE. Chapters 2-8 focus on the role of TVE in educational systems: "TVE in Cameroon" (Lucy Mbangwana); "TVE in Congo" (Gilbert Ndimina); "TVE in Ghana"(F. A. Baiden); "TVE in Kenya"(P. 0. Okaka); "TVE in Madagascar" (Victor Monantsoa); "TVE in Nigeria" (Egbe T. -

Expanded PDF Profile

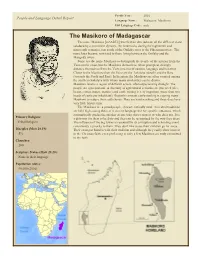

Profile Year: 2001 People and Language Detail Report Language Name: Malagasy, Masikoro ISO Language Code: msh The Masikoro of Madagascar The name Masikoro [mASikUr] was first used to indicate all the different clans subdued by a prominent dynasty, the Andrevola, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, just south of the Onilahy river to the Fiherenana river. The name later became restricted to those living between the Onilahy and the Mangoky rivers. Some use the name Masikoro to distinguish the people of the interior from the Vezo on the coast, but the Masikoro themselves, when prompted, strongly distance themselves from the Vezo in terms of custom, language and behavior. Closer to the Masikoro than the Vezo are the Tañalaña (South) and the Bara (towards the North and East). In literature the Masikoro are often counted among the southern Sakalava with whom many similarities can be drawn. Masikoro land is a region of difficult access, often experiencing drought. The people are agro-pastoral. A diversity of agricultural activities are practiced (rice, beans, cotton, maize, manioc) and cattle raising is very important (more than two heads of cattle per inhabitant). Recently rampant cattle-rustling is causing many Masikoro to reduce their cattle herds. They are hard-working and these days have very little leisure time. The Masikoro are a proud people, characteristically rural. Ancestral traditions are held high among them as is correct language use for specific situations, which automatically grades the speaker as one who shows respect or who does not. It is Primary Religion: a dishonor for them to be dirty and they can be recognized by the way they dress. -

Project Safidy Statement of Advocacy for Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights Education in Madagascar

Project Safidy Statement of Advocacy for Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights Education in Madagascar July 2017 SEED Madagascar Suite 7, 1a Beethoven St, London, W10 4LG, United Kingdom Villa Rabemanda, Ambinanikely, B.P. 318, Tolagnaro, Madagascar Tel: +44 (0)208 960 6629 Email: [email protected] Web: madagascar.co.uk UK Charity No. 1079121, Company No. 3796669 1 Project Safidy: Statement of Advocacy SEED Madagascar’s Project Safidy aims to provide rights-based, government-endorsed comprehensive sexual health education to lycée students throughout Madagascar. Through this education, young people can be empowered to take control of their sexual and reproductive health by learning how to avoid negative health outcomes such as sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancy, supported by the development of communication skills to assert their rights within relationships. Project Safidy employs a rights-based approach to educating young people on their sexual and reproductive health. This method aligns with a concept internationally known as Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR). The SRHR approach to education and health care, which has been adopted and endorsed by the United Nations, World Health Organization (WHO), International Planned Parenthood Federation and others, goes beyond simply providing technical health information, and promotes the personal choices and overall wellbeing of the whole individual. 1. Defining SRHR SRHR applies universal human rights to the sexual and reproductive health of individuals. In practice, SRHR ensures that in addition to having access to evidence-based information regarding sexual health and reproduction, individuals are also afforded the autonomy to make personal decisions about their sexual and reproductive wellbeing. -

Fombandrazana Vezo: Ethnic Identity and Subsistence

FOMBANDRAZANA VEZO: ETHNIC IDENTITY AND SUBSISTENCE STRATEGIES AMONG COASTAL FISHERS OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR by EARL FURMAN SANDERS (Under the Direction of THEODORE GRAGSON) ABSTRACT The complex dynamic among coastal peoples of western Madagascar involves spread of cultural elements due to extensive seasonal migrations, tribes and ethnic groups merging into progressively broader ethnic groups, distinctions based on interethnic and intra-ethnic boundaries, and lumping of peoples with remotely similar subsistence patterns which has perpetuated ethnonym vagaries. This study analyzes the cultural bases of the Vezo, a group of marine fishers inhabiting the west coast of Madagascar, with the intent of presenting a clearer image of what is entailed within the ethnonym, Vezo, both with respect to subsistence strategies and cultural identity. Three broad areas of inquiry, ethnohistory, ecological niche as understood from the Eltonian definition, and geographical scope inform the field research. Access to these areas leans heavily on oral histories, which in turn is greatly facilitated by intensive participant observation and work in the native language. The analysis shows that the Vezo constitute a distinct ethnic group composed of diverse named patrilineal descent groups. This ethnic group is defined by common origins and a shared sense of common history, which along with the origins of the taboos are maintained within their oral histories. Within the ethnonym, Vezo, there are subsistence as well as other cultural distinctions, most notably the taboos. These distinctions are the bases of the ethnic boundaries separating those who belong to the Vezo cultural group and others who are referred to as Vezo (Vezom-potake and Vezo-loatse) due to geographical disposition. -

Blue Ventures, Madagascar

Contents A word from the Chair About Blue Ventures About this guide Blue Ventures, Madagascar Velondriake Blue Ventures Projects Before you go Confirming your Place Paying your balance Forms Medical Forms Emergency contacts Flights When to fly Overland tour Internal flights Insurance Travel insurance DAN insurance Arriving and Departing International Domestic Money Visas Buying your kit Clothes/Equipment Dive Kit Dive Manuals Page 1 Whilst you’re there Internal Logistics Between Tana and Toliara Accommodation Recommendations Getting to Andavadoaka Things to do in Toliara The Expedition The Site The Team When you arrive Rules and Regulations Training Diving Other Projects you may or may not be involved in during your expedition Practicalities on site Health and Safety When you get home Feedback Reviews Spread the Word Check-ups Social Media Blogs Appendices Expedition Checklist Recommended background reading General background and natural history Terrestrial field guides Travel guides Useful websites Local Malagasy Word List Page 2 A word from the Chair Dear Volunteer, Many thanks for choosing to take part in a research expedition in Andavadoaka, Madagascar with Blue Ventures. Andavadoaka is particularly close to our heart as it is where Blue Ventures first begun back in 2003 and continues to be our flagship research site. The work we undertake in the region continues to go from strength to strength and we are truly thankful to our volunteers, without whom our ground-breaking initiatives could never have been realised. With the continued support of people like you, we can ensure that our work continues to improve the lives of thousands of the Vezo people of Southwest Madagascar and provide coastal communities the knowledge and skills they need to live sustainably. -

Information, Role Models and Perceived Returns to Education: Experimental Evidence from Madagascar∗

Information, Role Models and Perceived Returns to Education: Experimental Evidence from Madagascar∗ Trang Nguyen † Massachusetts Institute of Technology January 23, 2008 Job Market Paper Abstract This paper shows that increasing perceived returns to education strengthens incentives for schooling when agents underestimate the actual returns. I conducted a field experiment in Madagascar to study alternative ways to provide additional information about the returns to education: simply providing statistics versus using a role model–an actual person sharing his/her success story. Some argue that role models may be more effective than providing sta- tistics to a largely illiterate population. However, this proposition depends on how households update their beliefs based on the information the role model brings. Motivated by a model of belief formation, I randomly assigned schools to the role model intervention, the statistics inter- vention, or a combination of both. I find that providing statistics reduced the large gap between perceived returns and the statistics provided. As a result, it improved average test scores by 0.2 standard deviations. For those whose initial perceived returns were below the statistics, test scores improved by 0.37 standard deviations. Student attendance in statistics schools is also 3.5 percentage points higher than attendance in schools without statistics. Consistent with the theory, seeing a role model of poor background has a larger impact on poor children’s test scores than seeing someone of rich background. Combining a role model with statistics leads to smaller treatment effects than statistics alone, also consistent with the theory. The key implication of my results is that households lack information, but are able to process new information and change their decisions in a sophisticated manner. -

960 JP Games

Total Games: 2601 EU Games: 960 JP Games: 715 US Games: 887 Other Games: 39 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 100 All Time Favorites (U) {BOZE F0B9E32F} 1000 Bornes (F) {CMBF 694E13EE} 101 Dino DS (E) {C5NP A7232D52} 101 In 1 Explosive Megamix (E) {CQZP DE381815} 101 in 1 Sports Megamix (U) {B2NE B0EDCC89} 12 Family Games (E) {CI2P 0F445E14} 13-Sai no Hello Work DS (J) {YH3J C5129D15} 1912: Titanic Mystery (E) {BTIP F94EF422} 1-Hi-10-Fun de Egajou Zuni Kakeru DS (J) {YJZJ 3650D48F} 3 in 1: Solitaire, Mahjong and Tangram (E) {B7LP C974A55E} 4 Elements (E) {B4EX 8A1F92FC} 4 Elements (E) {B4EY E1CB6081} 42 All-Time Classics (E) {ATDP FBB7EDF4} 42 All-Time Classics (E) v1.1 {ATDP AB5D4CEA} 7 Wonders II (D) {B7WD 3F5772D0} 7 Wonders II (E) {B7WP DE7D995E} 7 Wonders II (E) {B7WX 3A583709} 7 Wonders II (U) {B7WE 5963D816} 7 Wonders of the Ancient World (E) {Y7WP 7BBAE54D} 7 Wonders of the Ancient World (U) {Y7WE C6D140EF} 700-Mannin no Atama o Yokusuru: Choukeisan DS - 13000-Mon + Image Keisan (J) {C3 KJ 8C7C2E5D} 7th Dragon (J) {CD6J 1171AA49} A Ressha de Ikou DS (J) {BARJ 4BDF1142} A Witch's Tale (U) {CW3E 7F741A38} A.S.H. Archaic Sealed Heat (J) {YASJ 93799D75} Ace Attorney Investigations: Miles Edgeworth (E) {C32P BE547C63} Ace Attorney Investigations: Miles Edgeworth (U) {C32E 04086E38} Actionloop (E) {APLP 4F406891} Addy: Do you speak English? (E) [Multi] {CAFX 87B73D5A} Advance Wars: Dark Conflict (E) {YW2P DF5E85E6} Advance Wars: Days of Ruin (U) {YW2E 6E2AAFE5} Advance Wars: Dual Strike (E) {AWRP