Learning to Be Vezo the Construction of Tile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar Is Recruiting for the Following Position

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar is recruiting for the following position: TEMPORARY LANGUAGE AND CROSS-CULTURAL FACILITATORS (LCF) The position is based at the Peace Corps Training Center, in Mantasoa, and is a short-term contract (typically 10 to 14 weeks). The primary role of the LCF is to train American trainees and volunteers in the Malagasy language and culture. Training usually take place at a residential training facilities where both LCFs and trainees/volunteers stay full-time. LCFs work under the direct supervision of Peace Corps Madagascar’s Language Coordinator. The duties of the LCF include, but are not limited to: Conduct Malagasy language training classes with small groups of American trainees or volunteers. Participate in the preparation of language training materials or resources. Conduct formal sessions and provide ongoing informal instruction and advice to trainees/volunteers regarding cultural adaptation and culturally appropriate behavior Interact with trainees outside of the classroom setting, providing informal training during meals, social events and other periods outside of classroom training Actively participate in staff language training Serve as the cultural model and guide for trainees/volunteers within their communities Establish and maintain a healthy, productive team spirit among the language staff and between support staff and Volunteer trainers Occasionally serve as Malagasy and English interpreters and/or translators. As requested, install the new Volunteers at their permanent sites; and train their community-based tutor as needed Required Qualifications: Completion of secondary school (Minimum BACC) Fluency in English, French and Malagasy Mastery in at least one of the following dialects: Betsileo, Antakarana, Antambahoaka, Antemoro, Antesaka, Antefasy, Sakalava boina, Antanosy, Antandroy, Sihanaka, Mahafaly, Bara. -

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic Versus Emblematic Criteria

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic versus Emblematic Criteria Alexander Adelaar UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE This paper gives an overview of the literature on Malagasy dialect variety and the various Malagasy dialect classifications that have been proposed. It rejects the often held view that the way Malagasy dialects reflect the Proto- Austronesian phoneme sequences *li and *ti is a basic criterion for their genetic division. While the linguistic innovations shown in, respectively, central dialects (Merina, Betsileo, Sihanaka, Tanala) and southwestern dia- lects (Vezo, Mahafaly, Tandroy) clearly show that these groups form separate historical divisions, the linguistic developments in other (northern, eastern, and western) dialects are more difficult to interpret. The differences between Malagasy dialects are generally rather contained and do not seem to be the result of separate migration waves or the arrival of linguistically different migrant groups. The paper ends with a list of subgrouping criteria that will be useful for future research into the history of Malagasy dialects. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 This paper investigates some of the early linguistic changes that have contributed to the dialect diversity of Malagasy, as well as the various classifications that have been proposed for Malagasy dialects. Malagasy is an Austronesian language directly related to some of the languages spoken in Central Kalimantan Province and South Kalimantan Province in Indonesian Borneo. Together with these languages, it forms the South East Barito (henceforth SEB) subgroup, which belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. A historical classification of dialects or languages should be based in the first place on the oldest linguistic changes that have happened in the dialect or language group in ques- tion. -

'The Vezo Are Not a Kind of People'. Identity, Difference and 'Ethnicity' Among a Fishing People of Western Madagascar

LSE Research Online Article (refereed) Rita Astuti 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar Originally published in American ethnologist, 22 (3). pp. 464-482 © 1995 by the Regents of the University of California on behalf of the American Ethnological Society. You may cite this version as: Astuti, Rita (1995). 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar [online]. London: LSE Research Online. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/archive/00000470 Available online: November 2005 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the publisher’s version remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk Contact LSE Research Online at: [email protected] 1 `THE VEZO ARE NOT A KIND OF PEOPLE' IDENTITY, DIFFERENCE AND `ETHNICITY' AMONG A FISHING PEOPLE OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR Rita Astuti London School of Economics Acknowledgments Fieldwork was conducted in two Vezo villages, Betania and Belo-sur Mer, between November 1987 and June 1989. -

Expanded PDF Profile

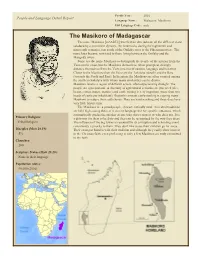

Profile Year: 2001 People and Language Detail Report Language Name: Malagasy, Masikoro ISO Language Code: msh The Masikoro of Madagascar The name Masikoro [mASikUr] was first used to indicate all the different clans subdued by a prominent dynasty, the Andrevola, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, just south of the Onilahy river to the Fiherenana river. The name later became restricted to those living between the Onilahy and the Mangoky rivers. Some use the name Masikoro to distinguish the people of the interior from the Vezo on the coast, but the Masikoro themselves, when prompted, strongly distance themselves from the Vezo in terms of custom, language and behavior. Closer to the Masikoro than the Vezo are the Tañalaña (South) and the Bara (towards the North and East). In literature the Masikoro are often counted among the southern Sakalava with whom many similarities can be drawn. Masikoro land is a region of difficult access, often experiencing drought. The people are agro-pastoral. A diversity of agricultural activities are practiced (rice, beans, cotton, maize, manioc) and cattle raising is very important (more than two heads of cattle per inhabitant). Recently rampant cattle-rustling is causing many Masikoro to reduce their cattle herds. They are hard-working and these days have very little leisure time. The Masikoro are a proud people, characteristically rural. Ancestral traditions are held high among them as is correct language use for specific situations, which automatically grades the speaker as one who shows respect or who does not. It is Primary Religion: a dishonor for them to be dirty and they can be recognized by the way they dress. -

Résultats Détaillés Toliary

RESULTATS SENATORIALES DU 29/12/2015 FARITANY: 6 TOLIARY BV reçus: 304 sur 304 HVM IND OBAMA FITIBA AVOTS AREMA MAPAR IND IND TIM IND IND MONIM AJFO E OMBILA MIARA- MASOA TSIMAN A TANIND HY DIA NDRO AVAKE N°BV Emplacement AP AT Inscrits Votants B N S E RAZA MAHER Y REGION 61 ANDROY BV reçus 58 sur 58 DISTRICT: 6101 AMBOVOMBE ANDROY BV reçus21 sur 21 01 AMBANISARIKA 0 0 8 8 0 8 5 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 0 0 0 0 02 AMBAZOA 0 0 8 7 1 6 3 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 03 AMBOHIMALAZA 0 0 8 8 0 8 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 04 AMBONAIVO 0 0 8 8 0 8 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 2 05 AMBONDRO 0 0 8 7 0 7 7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 06 AMBOVOMBE ANDRO 1 0 12 12 2 10 7 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 07 AMPAMATA 1 0 8 8 1 7 5 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 08 ANALAMARY 0 0 6 6 1 5 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 09 ANDALATANOSY 0 0 8 7 0 7 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 10 ANDOHARANO 1 0 6 5 2 3 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 11 ANDRAGNANIVO 0 0 6 6 0 6 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 12 ANJEKY ANKILIKIRA 1 0 8 8 1 7 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 13 ANTANIMORA SUD 0 0 8 8 0 8 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 14 ERADA 0 0 8 8 1 7 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 15 IMANOMBO 0 0 8 8 0 8 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 0 0 0 1 16 JAFARO 0 0 8 8 0 8 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 3 17 MAROALOMAINTE 1 0 8 8 2 6 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 1 18 MAROALOPOTY 0 7 8 7 7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 19 MAROVATO BEFENO 0 0 8 7 0 7 4 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 20 SIHANAMARO 0 0 8 8 0 8 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 21 TSIMANANADA 0 0 8 8 0 8 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 TOTAL DISTRICT 5 7 166 160 18 142 91 1 0 0 2 1 3 7 9 0 0 0 28 DISTRICT: 6102 BEKILY BV reçus20 sur -

Evaluation Des Impacts Du Cyclone Haruna Sur Les Moyens De Subsistance

1 EVALUATION DES IMPACTS DU CYCLONE HARUNA SUR LES MOYENS DE SUBSISTANCE, ET SUR LA SECURITE ALIMENTAIRE ET LA VULNERABILITE DES POPULATONS AFFECTEES commune rurale de Sokobory, Tuléar Tuléar I Photo crédit : ACF Cluster Sécurité Alimentaire et Moyens de Subsistance Avril 2013 2 TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES CARTES..................................................................................................................................... 3 LISTE DES GRAPHIQUES ..................................................................................................................................... 3 LISTE DES TABLEAUX ........................................................................................................................................... 4 ACRONYMES ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 RESUME ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 1. CONTEXTE ............................................................................................................................................ 8 2. OBJECTIFS ET METHODES ............................................................................................................. 11 2.1 OBJECTIFS ........................................................................................................................................... 11 2.2 METHODOLOGIE -

Fombandrazana Vezo: Ethnic Identity and Subsistence

FOMBANDRAZANA VEZO: ETHNIC IDENTITY AND SUBSISTENCE STRATEGIES AMONG COASTAL FISHERS OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR by EARL FURMAN SANDERS (Under the Direction of THEODORE GRAGSON) ABSTRACT The complex dynamic among coastal peoples of western Madagascar involves spread of cultural elements due to extensive seasonal migrations, tribes and ethnic groups merging into progressively broader ethnic groups, distinctions based on interethnic and intra-ethnic boundaries, and lumping of peoples with remotely similar subsistence patterns which has perpetuated ethnonym vagaries. This study analyzes the cultural bases of the Vezo, a group of marine fishers inhabiting the west coast of Madagascar, with the intent of presenting a clearer image of what is entailed within the ethnonym, Vezo, both with respect to subsistence strategies and cultural identity. Three broad areas of inquiry, ethnohistory, ecological niche as understood from the Eltonian definition, and geographical scope inform the field research. Access to these areas leans heavily on oral histories, which in turn is greatly facilitated by intensive participant observation and work in the native language. The analysis shows that the Vezo constitute a distinct ethnic group composed of diverse named patrilineal descent groups. This ethnic group is defined by common origins and a shared sense of common history, which along with the origins of the taboos are maintained within their oral histories. Within the ethnonym, Vezo, there are subsistence as well as other cultural distinctions, most notably the taboos. These distinctions are the bases of the ethnic boundaries separating those who belong to the Vezo cultural group and others who are referred to as Vezo (Vezom-potake and Vezo-loatse) due to geographical disposition. -

Blue Ventures, Madagascar

Contents A word from the Chair About Blue Ventures About this guide Blue Ventures, Madagascar Velondriake Blue Ventures Projects Before you go Confirming your Place Paying your balance Forms Medical Forms Emergency contacts Flights When to fly Overland tour Internal flights Insurance Travel insurance DAN insurance Arriving and Departing International Domestic Money Visas Buying your kit Clothes/Equipment Dive Kit Dive Manuals Page 1 Whilst you’re there Internal Logistics Between Tana and Toliara Accommodation Recommendations Getting to Andavadoaka Things to do in Toliara The Expedition The Site The Team When you arrive Rules and Regulations Training Diving Other Projects you may or may not be involved in during your expedition Practicalities on site Health and Safety When you get home Feedback Reviews Spread the Word Check-ups Social Media Blogs Appendices Expedition Checklist Recommended background reading General background and natural history Terrestrial field guides Travel guides Useful websites Local Malagasy Word List Page 2 A word from the Chair Dear Volunteer, Many thanks for choosing to take part in a research expedition in Andavadoaka, Madagascar with Blue Ventures. Andavadoaka is particularly close to our heart as it is where Blue Ventures first begun back in 2003 and continues to be our flagship research site. The work we undertake in the region continues to go from strength to strength and we are truly thankful to our volunteers, without whom our ground-breaking initiatives could never have been realised. With the continued support of people like you, we can ensure that our work continues to improve the lives of thousands of the Vezo people of Southwest Madagascar and provide coastal communities the knowledge and skills they need to live sustainably. -

Evolution De La Couverture De Forets Naturelles a Madagascar

EVOLUTION DE LA COUVERTURE DE FORETS NATURELLES A MADAGASCAR 1990-2000-2005 mars 2009 La publication de ce document a été rendue possible grâce à un support financier du Peuple Americain à travers l’USAID (United States Agency for International Development). L’analyse de la déforestation pour les années 1990 et 2000 a été fournie par Conservation International. MINISTERE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT, DES FORETS ET DU TOURISME Le présent document est un rapport du Ministère de l’Environnement, des Forêts et du Tourisme (MEFT) sur l’état de de l’évolution de la couverture forestière naturelle à Madagascar entre 1990, 2000, et 2005. Ce rapport a été préparé par Conservation International. Par ailleurs, les personnes suivantes (par ordre alphabétique) ont apporté leur aimable contribution pour sa rédaction: Andrew Keck, James MacKinnon, Norotiana Mananjean, Sahondra Rajoelina, Pierrot Rakotoniaina, Solofo Ralaimihoatra, Bruno Ramamonjisoa, Balisama Ramaroson, Andoniaina Rambeloson, Rija Ranaivosoa, Pierre Randriamantsoa, Andriambolantsoa Rasolohery, Minoniaina L. Razafindramanga et Marc Steininger. Le traitement des imageries satellitaires a été réalisé par Balisama Ramaroson, Minoniaina L. Razafindramanga, Pierre Randriamantsoa et Rija Ranaivosoa et les cartes ont été réalisées par Andriambolantsoa Rasolohery. La réalisation de ce travail a été rendu possible grâce a une aide financière de l’United States Agency for International Development (USAID) et mobilisé à travers le projet JariAla. En effet, ce projet géré par International Resources Group (IRG) fournit des appuis stratégiques et techniques au MEFT dans la gestion du secteur forestier. Ce rapport devra être cité comme : MEFT, USAID et CI, 2009. Evolution de la couverture de forêts naturelles à Madagascar, 1990- 2000-2005. -

Liste Candidatures Maires Atsimo Andrefana

NOMBRE DISTRICT COMMUNE ENTITE NOM ET PRENOM(S) CANDIDATS CANDIDATS ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA AMPANIHY OUEST AMBOROPOTSY 1 VAKISOA (ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA) AMPANIHY OUEST AMBOROPOTSY 1 INDEPENDANT SOLO (INDEPENDANT SOLO) BESADA AMPANIHY OUEST AMBOROPOTSY 1 AVI (ASA VITA NO IFAMPITSARANA) TOVONDRAOKE AMPANIHY OUEST AMBOROPOTSY 1 TIM (TIAKO I MADAGASIKARA) REMAMORITSY AMPANIHY OUEST AMBOROPOTSY 1 HIARAKA ISIKA (HIARAKA ISIKA) SORODO INDEPENDANT MOSA Jean Baptiste (INDEPENDANT AMPANIHY OUEST AMPANIHY CENTRE 1 FOTOTSANAKE MOSA Jean Baptiste) ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA AMPANIHY OUEST AMPANIHY CENTRE 1 TOVONASY (ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA) ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA AMPANIHY OUEST ANDROKA 1 ESOLONDRAY Raymond (ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA) AMPANIHY OUEST ANDROKA 1 TIM (TIAKO I MADAGASIKARA) LAHIVANOSON Jacques AMPANIHY OUEST ANDROKA 1 MMM (MALAGASY MIARA MIAINGA) KOLOAVISOA René INDEPENDANT TSY MIHAMBO RIE (INDEPENDANT AMPANIHY OUEST ANDROKA 1 EMANINTSINDRAZA TSY MIHAMBO RIE) INDEPENDANT ESOATEHY Victor (INDEPENDANT AMPANIHY OUEST ANDROKA 1 EFANOMBO ESOATEHY Victor) ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA AMPANIHY OUEST ANKILIABO 1 ZOENDRAZA Fanilina (ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA) INDEPENDANT TAHIENANDRO (INDEPENDANT AMPANIHY OUEST ANKILIABO 1 EMAZINY Mana TAHIENANDRO) AMPANIHY OUEST ANKILIABO 1 TIM (TIAKO I MADAGASIKARA) RASOBY AMPANIHY OUEST ANKILIABO 1 HIARAKA ISIKA (HIARAKA ISIKA) MAHATALAKE ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA AMPANIHY OUEST -

The Origins of the Malagasy People, Some Certainties and a Few Mysteries

Instituto de Estudos Avanc¸ados Transdisciplinares Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais The origins of the Malagasy people, some certainties and a few mysteries Maurizio Serva1 Abstract The Malagasy language belongs to the Greater Barito East group of the Austronesian family, the language most closely connected to Malagasy dialects is Maanyan (Kalimantan), but Malay as well other Indonesian and Philippine languages are also related. The African contribution is very high in the Malagasy genetic make-up (about 50%) but negligible in the language. Because of the linguistic link, it is widely accepted that the island was settled by Indonesian sailors after a maritime trek but date and place of landing are still debated. The 50% Indonesian genetic contribution to present Malagasy points in a different direction then Maanyan for the Asian ancestry, therefore, the ethnic composition of the Austronesian settlers is also still debated. In this talk I mainly review the joint research of Filippo Petroni, Dima Volchenkov, Soren¨ Wichmann and myself which tries to shed new light on these problems. The key point is the application of a new quantitative methodology which is able to find out the kinship relations among languages (or dialects). New techniques are also introduced in order to extract the maximum information from these relations concerning time and space patterns. Keywords Malagasy dialects — Austronesian languages — Lexicostatistics — Malagasy origins 1Dipartimento di Ingegneria e Scienze dell’Informazione e Matematica, Universita` dell’Aquila, I-67010 L’Aquila, Italy 1. Introduction The Austronesian expansion, which very likely started from Taiwan or from the south of China [Gray and Jordan, 2000, Hurles et al 2005], is probably the most spectacular event of maritime colonization in human history as it can be appreci- ated in Fig. -

Exploring Discourses of Indigeneity and Rurality in Mikea Forest Environmental Governance

MADAGASCAR CONSERVATION & DEVELOPMENT VOLUME 7 | ISSUE 2S — NOVEMBER 2012 PAGE 58 ARTICLE http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mcd.v7i2S.2 Exploring discourses of indigeneity and rurality in Mikea Forest environmental governance Amber R. Huff The University of Georgia 250A Baldwin Hall, Jackson Street Athens, Georgia, U.S.A 30602-1619 E - mail: amber.rosalyn @ gmail.com ABSTRACT entre ces représentations et les réalités du terrain : les fonde- This article examines discourses of indigeneity and rurality that ments de l’identité locale ne correspondent pas aux définitions define and classify different categories of resource users in officielles de l’autochtonie présentée dans les documents du the context of Mikea Forest environmental governance. Many développement. Les Mikea et les populations voisines sont en Malagasy peoples live in, have deep cultural ties with, and fait largement interdépendants et tous pratiquent un éventail directly depend on the island’s forests, but Mikea people are the d’activités économiques qui varient en fonction des saisons, only to be legally recognized as ‘indigenous peoples’ as defined des compétences ou des demandes du marché. Contrairement by Operational Directive 4.20 of the World Bank. In policy docu- aux représentations officielles présentant la culture des Mikea ments, scholarship, and media productions, Mikea people are comme étant unique et autonome, les Mikea appartiennent represented as a small, culturally distinct population of primitive aux mêmes clans et partagent les mêmes pratiques que leurs forest foragers. In contrast, other subsistence producers living voisins jugés illégitimes quant à la gestion des territoires. in the region are represented as invasive and harmful to Mikea L’histoire montre en outre une longue participation des peuples people and the Mikea Forest environment.