Malagasy Dialects and the Peopling of Madagascar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar Is Recruiting for the Following Position

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar is recruiting for the following position: TEMPORARY LANGUAGE AND CROSS-CULTURAL FACILITATORS (LCF) The position is based at the Peace Corps Training Center, in Mantasoa, and is a short-term contract (typically 10 to 14 weeks). The primary role of the LCF is to train American trainees and volunteers in the Malagasy language and culture. Training usually take place at a residential training facilities where both LCFs and trainees/volunteers stay full-time. LCFs work under the direct supervision of Peace Corps Madagascar’s Language Coordinator. The duties of the LCF include, but are not limited to: Conduct Malagasy language training classes with small groups of American trainees or volunteers. Participate in the preparation of language training materials or resources. Conduct formal sessions and provide ongoing informal instruction and advice to trainees/volunteers regarding cultural adaptation and culturally appropriate behavior Interact with trainees outside of the classroom setting, providing informal training during meals, social events and other periods outside of classroom training Actively participate in staff language training Serve as the cultural model and guide for trainees/volunteers within their communities Establish and maintain a healthy, productive team spirit among the language staff and between support staff and Volunteer trainers Occasionally serve as Malagasy and English interpreters and/or translators. As requested, install the new Volunteers at their permanent sites; and train their community-based tutor as needed Required Qualifications: Completion of secondary school (Minimum BACC) Fluency in English, French and Malagasy Mastery in at least one of the following dialects: Betsileo, Antakarana, Antambahoaka, Antemoro, Antesaka, Antefasy, Sakalava boina, Antanosy, Antandroy, Sihanaka, Mahafaly, Bara. -

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic Versus Emblematic Criteria

Malagasy Dialect Divisions: Genetic versus Emblematic Criteria Alexander Adelaar UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE This paper gives an overview of the literature on Malagasy dialect variety and the various Malagasy dialect classifications that have been proposed. It rejects the often held view that the way Malagasy dialects reflect the Proto- Austronesian phoneme sequences *li and *ti is a basic criterion for their genetic division. While the linguistic innovations shown in, respectively, central dialects (Merina, Betsileo, Sihanaka, Tanala) and southwestern dia- lects (Vezo, Mahafaly, Tandroy) clearly show that these groups form separate historical divisions, the linguistic developments in other (northern, eastern, and western) dialects are more difficult to interpret. The differences between Malagasy dialects are generally rather contained and do not seem to be the result of separate migration waves or the arrival of linguistically different migrant groups. The paper ends with a list of subgrouping criteria that will be useful for future research into the history of Malagasy dialects. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 This paper investigates some of the early linguistic changes that have contributed to the dialect diversity of Malagasy, as well as the various classifications that have been proposed for Malagasy dialects. Malagasy is an Austronesian language directly related to some of the languages spoken in Central Kalimantan Province and South Kalimantan Province in Indonesian Borneo. Together with these languages, it forms the South East Barito (henceforth SEB) subgroup, which belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. A historical classification of dialects or languages should be based in the first place on the oldest linguistic changes that have happened in the dialect or language group in ques- tion. -

Evaluating the Effects of Colonialism on Deforestation in Madagascar: a Social and Environmental History

Evaluating the Effects of Colonialism on Deforestation in Madagascar: A Social and Environmental History Claudia Randrup Candidate for Honors in History Michael Fisher, Thesis Advisor Oberlin College Spring 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………… 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Methods and Historiography Chapter 1: Deforestation as an Environmental Issue.……………………………………… 20 The Geography of Madagascar Early Human Settlement Deforestation Chapter 2: Madagascar: The French Colony, the Forested Island…………………………. 28 Pre-Colonial Imperial History Becoming a French Colony Elements of a Colonial State Chapter 3: Appropriation and Exclusion…………………………………………………... 38 Resource Appropriation via Commercial Agriculture and Logging Concessions Rhetoric and Restriction: Madagascar’s First Protected Areas Chapter 4: Attitudes and Approaches to Forest Resources and Conservation…………….. 50 Tensions Mounting: Political Unrest Post-Colonial History and Environmental Trends Chapter 5: A New Era in Conservation?…………………………………………………... 59 The Legacy of Colonialism Cultural Conservation: The Case of Analafaly Looking Forward: Policy Recommendations Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………. 67 Selected Bibliography……………………………………………………………………… 69 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper was made possible by a number of individuals and institutions. An Artz grant and a Jerome Davis grant through Oberlin College’s History department and a Doris Baron Student Research Fund award through the Environmental Studies department supported -

Men and Women of the Forest. Livelihood Strategies And

Men and women of the forest Livelihood strategies and conservation from a gender perspective in Ranomafana National Park, Madagascar Laura Järvilehto Master’s thesis in Environmental Sciences Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences University of Helsinki November 2005 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Faculty of Biosciences Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences Tekijä – Författare – Author Laura Järvilehto Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Men and women of the forest – Livelihood strategies and conservation from a gender perspective in Ranomafana National Park, Madagascar Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Environmental Sciences Työn laji– Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä – Sidoantal – Number of pages Master’s thesis November 2005 50 pages Tiivistelmä Referat – Abstract The objective of this study is twofold: Firstly, to investigate how men and women living in Tanala villages in the Ranomafana National Park buffer zone differ in their natural resource use and livelihood. Secondly, based on this information, the intention is to find out how the establishment of the park has influenced people living in the buffer zone from the gender point of view. The data have been gathered mainly by using semi-structured interviews. Group interviews and individual interviews were carried out in three buffer zone villages. In addition, members of the park personnel were interviewed, observations were made during the visits to the villages and documents related to the planning and the administration of the park were investigated. The data were analysed using qualitative content analysis. It seems that Tanala women and men relate to their environment in a rather similar way and that they have quite equal rights considering the use and the control of natural resources. -

Linguistics for Archaeologists: Principles, Methods and the Case of the Incas

Linguistics for Archaeologists Linguistics for Archaeologists: Principles, Methods and the Case of the Incas Paul Heggarty1 Like archaeologists, linguists and geneticists too use the data and methods of their dis‑ ciplines to open up their own windows onto our past. These disparate visions of human prehistory cry out to be reconciled into a coherent holistic scenario, yet progress has long been frustrated by interdisciplinary disputes and misunderstandings (not least about Indo‑European). In this article, a comparative‑historical linguist sets out, to his intended audience of archaeologists, the core principles and methods of his discipline that are of relevance to theirs. They are first exemplified for the better‑known languages of Europe, before being put into practice in a lesser‑known case‑study. This turns to the New World, setting its greatest indigenous ‘Empire’, that of the Incas, alongside its greatest surviving language family today, Quechua. Most Andean archaeologists assume a straightforward association between these two. The linguistic evidence, however, exposes this as nothing but a popular myth, and writes instead a wholly new script for the prehistory of the Andes — which now awaits an archaeological story to match. 1. Archaeology and linguistics genetic methods from the biological sciences now being applied to language data. In a much discussed Recent years have seen growing interest in a ‘new syn- paper in Nature, Gray & Atkinson (2003) put forward thesis’ between the disciplines of archaeology, genetics a phylogenetic analysis of Indo-European languages, and linguistics, at the point where all three intersect based on comparative vocabulary lists, which falls in seeking a coherent picture of the distant origins of neatly in line with the ‘out of Anatolia’ hypothesis. -

'The Vezo Are Not a Kind of People'. Identity, Difference and 'Ethnicity' Among a Fishing People of Western Madagascar

LSE Research Online Article (refereed) Rita Astuti 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar Originally published in American ethnologist, 22 (3). pp. 464-482 © 1995 by the Regents of the University of California on behalf of the American Ethnological Society. You may cite this version as: Astuti, Rita (1995). 'The Vezo are not a kind of people'. Identity, difference and 'ethnicity' among a fishing people of western Madagascar [online]. London: LSE Research Online. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/archive/00000470 Available online: November 2005 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the publisher’s version remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk Contact LSE Research Online at: [email protected] 1 `THE VEZO ARE NOT A KIND OF PEOPLE' IDENTITY, DIFFERENCE AND `ETHNICITY' AMONG A FISHING PEOPLE OF WESTERN MADAGASCAR Rita Astuti London School of Economics Acknowledgments Fieldwork was conducted in two Vezo villages, Betania and Belo-sur Mer, between November 1987 and June 1989. -

Expanded PDF Profile

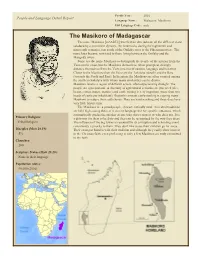

Profile Year: 2001 People and Language Detail Report Language Name: Malagasy, Masikoro ISO Language Code: msh The Masikoro of Madagascar The name Masikoro [mASikUr] was first used to indicate all the different clans subdued by a prominent dynasty, the Andrevola, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, just south of the Onilahy river to the Fiherenana river. The name later became restricted to those living between the Onilahy and the Mangoky rivers. Some use the name Masikoro to distinguish the people of the interior from the Vezo on the coast, but the Masikoro themselves, when prompted, strongly distance themselves from the Vezo in terms of custom, language and behavior. Closer to the Masikoro than the Vezo are the Tañalaña (South) and the Bara (towards the North and East). In literature the Masikoro are often counted among the southern Sakalava with whom many similarities can be drawn. Masikoro land is a region of difficult access, often experiencing drought. The people are agro-pastoral. A diversity of agricultural activities are practiced (rice, beans, cotton, maize, manioc) and cattle raising is very important (more than two heads of cattle per inhabitant). Recently rampant cattle-rustling is causing many Masikoro to reduce their cattle herds. They are hard-working and these days have very little leisure time. The Masikoro are a proud people, characteristically rural. Ancestral traditions are held high among them as is correct language use for specific situations, which automatically grades the speaker as one who shows respect or who does not. It is Primary Religion: a dishonor for them to be dirty and they can be recognized by the way they dress. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Time Depth in Historical Linguistics”, Edited by Colin Renfrew, April

Time Depth 1 Review of “Time Depth in Historical Linguistics”, edited by Colin Renfrew, April McMahon, and Larry Trask Brett Kessler Washington University in St. Louis Brett Kessler Psychology Department Washington University in St. Louis Campus Box 1125 One Brookings Drive St. Louis MO 63130-4899 USA Email: [email protected] FAX: 1-314-935-7588 Time Depth 2 Review of “Time Depth in Historical Linguistics”, edited by Colin Renfrew, April McMahon, and Larry Trask Time depth in historical linguistics. Ed. by Colin Renfrew, April McMahon, and Larry Trask. (Papers in the prehistory of languages.) Cambridge, England: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2000. Distributed by Oxbow Books. 2 vol. (xiv, 681 p.) paperback, 50 GBP. http://www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk/Publications/Time-depth.htm This is a collection of 27 papers, mostly presentations at a symposium held at the McDonald Institute in 1999. Contributions focus on two related issues: methods for establishing absolute chronology, and linguistic knowledge about the remote past. Most papers are restatements of the authors’ well-known theories, but many contain innovations, and some do describe new work. The ideological balance of the collection feels just left of center. We do not find here wild multilateral phantasms, reconstructions of Proto-World vocabulary, or idylls about pre-Indo-European matriarchal society. Or not much. These are mostly sober academics pushing the envelope in attempts to reason under extreme uncertainty. One of the recurrent themes was that the development of agriculture may drive the expansion of language families and therefore imply a date for the protolanguage. Colin Renfrew describes his idea that that is what happened in the case of Indo-European (IE): PIE was introduced into Europe at an early date, perhaps 8,000 BC. -

Lesson 2 the People of Madagascar

LUTHERAN HOUR MINISTRIES online mission trip Curriculum LESSON 2 THE PEOPLE OF MADAGASCAR 660 MASON RIDGE CENTER DRIVE, SAINT LOUIS, MO 63141 | LHM.ORG 0117 LHM – MADAGASCAR Lesson 2 – The People of Madagascar Population On the map, Madagascar is very close to the eastern edge of Africa. This closeness would lead people to conclude that the inhabitants of Madagascar are predominately African. This is not true. The native inhabitants of Madagascar are the Malagasy (pronounced mah-lah-GAH-shee), who originated in Malaysia and Indonesia and reached Madagascar about 1,500 years ago. The language, customs, and physical appearance of today’s Malagasy reflect their Asian ancestry. Nearly 22.5 million people live in modern Madagascar. The annual growth rate of three percent combined with an average life expectancy of only sixty- four years gives Madagascar a young population. About sixty percent of the Malagasy people are less than twenty-five years old. Thirty-five percent of the adult population is classified as illiterate. More than ninety-five percent of the population is of Malagasy origin. The other five percent is made up of French, Comorians, Indo-Pakistanis, and Chinese peoples. The Malagasy are divided into 20 distinct ethnic groups, each of which occupies a certain area of the island. These groups originally started as loosely organized clans. Each clan remained apart from each other clan, marrying only within its clan. The clans developed into separate ethnic groups. Today there is an increased amount of intermarriage between the clans blurring the lines of distinction. All groups consider themselves as equally Malagasy. -

Uncoveringhistory

People Uncovering history Nancy Grace Nancy Graceisadetectiveand storyteller who finds clues from the past. ne of the most memorable moments the 1970s. What does it feel liketobethe Ofrom Nancy Grace’s33-year career person who steps down through the ground is the time she took a4,000-year-old skeleton to find thingsthathaven’t beenseen for to the dentist. As an archaeologist, thousands of years?Grace tells The Week Gracespends her days researching Junior,“Standing on thatsurface, past human activities from thefirst person to stand on it clues that areleft behind for4,000 years, is likewhen underground. When the snow fallsand you’re astorm ripped up atree the first person to put in Dorset and revealed your foot on the snow. acrushed skeleton, Youdon’t evertakeit Graceknew she had to forgranted.” find out more. Graceisalways on the With the lower hunt for new finds at jawbone in hand, she National Trust properties headed to her dentist. An NancyGrace across the country,using old X-raymachine wasusedtofind lookingfor clues. maps and recordsaswell as out that the person had signs of gum cutting-edge technology to work out where disease. Further research showed that the historic items could be lying undiscoverreed.d. person wasroughly 26 years old when she She explains, “Wefind rubbish that LL died, about 4,000 years ago. people would have thrown away, SME ATER and Graceispartofthe archaeology team remnants of buildings that have YOUL et,G race ite i n D ors smell of at the National Trust, an organisation that fallen down, and it’slikebeing a At a s oticed the en preserves historic buildings and areasof detective looking for evidence. -

A Strategy to Reach Animistic People in Madagascar

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2006 A Strategy To Reach Animistic People in Madagascar Jacques Ratsimbason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Ratsimbason, Jacques, "A Strategy To Reach Animistic People in Madagascar" (2006). Dissertation Projects DMin. 690. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/690 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A STRATEGY TO REACH ANIMISTIC PEOPLE IN MADAGASCAR by Jacques Ratsimbason Adviser: Bruce Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A STRATEGY TO REACH ANIMISTIC PEOPLE IN MADAGASCAR Name of researcher: Jacques Ratsimbason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Bruce Bauer, D.Miss. Date completed: August 2006 Problem The majority of the Malagasy people who live in Madagascar are unreached with the gospel message. A preliminary investigation of current literature indicated that 50 percent of the Malagasy are followers of traditional religions. This present study was to develop a strategy to reach the animistic people with the gospel message. Method This study presents Malagasy people, their social characteristics, population, worldviews, and lifestyles. A study;and evaluation of Malagasy beliefs and practices were developed using Hiebert's model of critical contextualization. Results The study reveals that the Seventh-day Adventist Church must update its evangelistic methods to reach animistic people and finish the gospel commission in Madagascar.