Why Joyce Is and Is Not Responsible for the Quark in Contemporary Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1974.Ulysses in Nighttown.Pdf

The- UNIVERSITY· THEAtl\E Present's ULYSSES .IN NIGHTTOWN By JAMES JOYCE Dramatized and Transposed by MARJORIE BARKENTIN Under the Supervision of PADRAIC COLUM Direct~ by GLENN ·cANNON Set and ~O$tume Design by RICHARD MASON Lighting Design by KENNETH ROHDE . Teehnicai.Direction by MARK BOYD \ < THE CAST . ..... .......... .. -, GLENN CANNON . ... ... ... : . ..... ·. .. : ....... ~ .......... ....... ... .. Narrator. \ JOHN HUNT . ......... .. • :.·• .. ; . ......... .. ..... : . .. : ...... Leopold Bloom. ~ . - ~ EARLL KINGSTON .. ... ·. ·. , . ,. ............. ... .... Stephen Dedalus. .. MAUREEN MULLIGAN .......... .. ... .. ......... ............ Molly Bloom . .....;. .. J.B. BELL, JR............. .•.. Idiot, Private Compton, Urchin, Voice, Clerk of the Crown and Peace, Citizen, Bloom's boy, Blacksmith, · Photographer, Male cripple; Ben Dollard, Brother .81$. ·cavalier. DIANA BERGER .......•..... :Old woman, Chifd, Pigmy woman, Old crone, Dogs, ·Mary Driscoll, Scrofulous child, Voice, Yew, Waterfall, :Sutton, Slut, Stephen's mother. ~,.. ,· ' DARYL L. CARSON .. ... ... .. Navvy, Lynch, Crier, Michael (Archbishop of Armagh), Man in macintosh, Old man, Happy Holohan, Joseph Glynn, Bloom's bodyguard. LUELLA COSTELLO .... ....... Passer~by, Zoe Higgins, Old woman. DOYAL DAVIS . ....... Simon Dedalus, Sandstrewer motorman, Philip Beau~ foy, Sir Frederick Falkiner (recorder ·of Dublin), a ~aviour and · Flagger, Old resident, Beggar, Jimmy Henry, Dr. Dixon, Professor Maginni. LESLIE ENDO . ....... ... Passer-by, Child, Crone, Bawd, Whor~. -

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 Through 2009

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 through 2009 COMPILED BY MOLLY BLA C K VERENE TABLE OF CON T EN T S PART I. Books A. Monographs . .84 B. Collected Volumes . 98 C. Dissertations and Theses . 111 D. Journals......................................116 PART II. Essays A. Articles, Chapters, et cetera . 120 B. Entries in Reference Works . 177 C. Reviews and Abstracts of Works in Other Languages ..180 PART III. Translations A. English Translations ............................186 B. Reviews of Translations in Other Languages.........192 PART IV. Citations...................................195 APPENDIX. Bibliographies . .302 83 84 NEW VICO STUDIE S 27 (2009) PART I. BOOKS A. Monographs Adams, Henry Packwood. The Life and Writings of Giambattista Vico. London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reprinted New York: Russell and Russell, 1970. REV I EWS : Gianturco, Elio. Italica 13 (1936): 132. Jessop, T. E. Philosophy 11 (1936): 216–18. Albano, Maeve Edith. Vico and Providence. Emory Vico Studies no. 1. Series ed. D. P. Verene. New York: Peter Lang, 1986. REV I EWS : Daniel, Stephen H. The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography, n.s. 12 (1986): 148–49. Munzel, G. F. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 173–75. Simon, L. Canadian Philosophical Reviews 8 (1988): 335–37. Avis, Paul. The Foundations of Modern Historical Thought: From Machiavelli to Vico. Beckenham (London): Croom Helm, 1986. REV I EWS : Goldie, M. History 72 (1987): 84–85. Haddock, Bruce A. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 185–86. Bedani, Gino L. C. Vico Revisited: Orthodoxy, Naturalism and Science in the ‘Scienza nuova.’ Oxford: Berg, 1989. REV I EWS : Costa, Gustavo. New Vico Studies 8 (1990): 90–92. -

A Manual for the Advanced Study of James Joyce's Finnegans Wake in 130 Volumes

1 A Manual for the Advanced Study of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake in 130 Volumes 31802 pages by C. George Sandulescu and Lidia Vianu FW 167.28 My unchanging Word is sacred. The word is my Wife, to exponse and expound, to vend and to velnerate, and may the curlews crown our nuptias! Till Breath us depart! Wamen. Beware would you change with my years. Be as young as your grandmother! The ring man in the rong shop but the rite words by the rote order! Ubi lingua nuncupassit, ibi fas! Adversus hostem semper sac! FW 219.16 And wordloosed over seven seas crowdblast in celtelleneteutoslavzendlatinsoundscript. 2 Title Launched on Vol. The Romanian Lexicon of Finnegans Wake. 75pp 11 November 1. 2011 http://editura.mttlc.ro/sandulescu.lexicon-of- romanian-in-FW.html Vol. Helmut Bonheim’s German Lexicon of Finnegans 217pp 7 December 2. Wake. 2011 http://editura.mttlc.ro/Helmut.Bonheim-Lexicon- of-the-German-in-FW.html Vol. A Lexicon of Common Scandinavian in Finnegans 195pp 13 January 3. Wake. 2012 http://editura.mttlc.ro/C-G.Sandulescu-A- Lexicon-of-Common-Scandinavian-in-FW.html Vol. A Lexicon of Allusions and Motifs in Finnegans 263pp 11 February 4. Wake. 2012 http://editura.mttlc.ro/G.Sandulescu-Lexicon-of- Allusions-and-Motifs-in-FW.html Vol. A Lexicon of ‘Small’ Languages in Finnegans Wake. 237pp 7 March 2012 5. Dedicated to Stephen J. Joyce. http://editura.mttlc.ro/sandulescu-small- languages-fw.html Vol. A Total Lexicon of Part Four of Finnegans Wake. 411pp 31 March 6. -

James Joyce – Through Film

U3A Dunedin Charitable Trust A LEARNING OPTION FOR THE RETIRED Series 2 2015 James Joyce – Through Film Dates: Tuesday 2 June to 7 July Time: 10:00 – 12:00 noon Venue: Salmond College, Knox Street, North East Valley Enrolments for this course will be limited to 55 Course Fee: $40.00 Tea and Coffee provided Course Organiser: Alan Jackson (473 6947) Course Assistant: Rosemary Hudson (477 1068) …………………………………………………………………………………… You may apply to enrol in more than one course. If you wish to do so, you must indicate your choice preferences on the application form, and include payment of the appropriate fee(s). All applications must be received by noon on Wednesday 13 May and you may expect to receive a response to your application on or about 25 May. Any questions about this course after 25 May should be referred to Jane Higham, telephone 476 1848 or on email [email protected] Please note, that from the beginning of 2015, there is to be no recording, photographing or videoing at any session in any of the courses. Please keep this brochure as a reminder of venue, dates, and times for the courses for which you apply. JAMES JOYCE – THROUGH FILM 2 June James Joyce’s Dublin – a literary biography (50 min) This documentary is an exploration of Joyce’s native city of Dublin, discovering the influences and settings for his life and work. Interviewees include Robert Nicholson (curator of the James Joyce museum), David Norris (Trinity College lecturer and Chair of the James Joyce Cultural Centre) and Ken Monaghan (Joyce’s nephew). -

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce's Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL a Thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingh

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce’s Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY English Studies School of English, Drama, American & Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham October 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis considers the imbrications created by James Joyce in his writing with the work of John Milton, through allusions, references and verbal echoes. These imbrications are analysed in light of the concept of ‘presence’, based on theories of intertextuality variously proposed by John Shawcross, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, and Eelco Runia. My analysis also deploys Gumbrecht’s concept of stimmung in order to explain how Joyce incorporates a Miltonic ‘atmosphere’ that pervades and enriches his characters and plot. By using a chronological approach, I show the subtlety of Milton’s presence in Joyce’s writing and Joyce’s strategy of weaving it into the ‘fabric’ of his works, from slight verbal echoes in Joyce’s early collection of poems, Chamber Music, to a culminating mass of Miltonic references and allusions in the multilingual Finnegans Wake. -

Ulysses: the Novel, the Author and the Translators

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 21-27, January 2011 © 2011 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.1.1.21-27 Ulysses: The Novel, the Author and the Translators Qing Wang Shandong Jiaotong University, Jinan, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—A novel of kaleidoscopic styles, Ulysses best displays James Joyce’s creativity as a renowned modernist novelist. Joyce maneuvers freely the English language to express a deep hatred for religious hypocrisy and colonizing oppressions as well as a well-masked patriotism for his motherland. In this aspect Joyce shares some similarity with his Chinese translator Xiao Qian, also a prolific writer. Index Terms—style, translation, Ulysses, James Joyce, Xiao Qian I. INTRODUCTION James Joyce (1882-1941) is regarded as one of the most innovative novelists of the 20th century. For people who are interested in modernist novels, Ulysses is an enormous aesthetic achievement. Attridge (1990, p.1) asserts that the impact of Joyce‟s literary revolution was such that “far more people read Joyce than are aware of it”, and that few later novelists “have escaped its aftershock, even when they attempt to avoid Joycean paradigms and procedures.” Gillespie and Gillespie (2000, p.1) also agree that Ulysses is “a work of art rivaled by few authors in this or any century.” Ezra Pound was one of the first to recognize the gift in Joyce. He was convinced of the greatness of Ulysses no sooner than having just read the manuscript for the first part of the novel in 1917. -

JOYCE and the JEWS Also by Ira B

JOYCE AND THE JEWS Also by Ira B. Nadel BIOGRAPHY: Fiction, Fact and Form GERTRUDE STEIN AND THE MAKING OF LITERATURE (editor with Shirley Neuman) GEORGE ORWELL: A Reassessment (editor with Peter Buitenhuis) Joyce and the Je-ws Culture and Texts Ira B. Nadel Professor of English University of British Columbia M MACMILLAN PRESS © Ira B. Nadel 1989 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1989 978-0-333-38352-0 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended), or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright licenSing Agency, 33-4 Alfred Place, London WC1E 7DP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 1989 Published by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world Typeset by Wessex Typesetters (Division of The Eastern Press Ltd) Frome, Somerset British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Nadel, Ira Bruce Joyce and the Jews: Culture and texts. 1. Joyce, James, 1882-1941--Criticism and interpretation I. Title 823'.912 PR6019.09Z1 ISBN 978-1-349-07654-3 ISBN 978-1-349-07652-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-07652-9 In memory of my father Isaac David Nadel and for Ryan and Dara 'We Jews are not painters. -

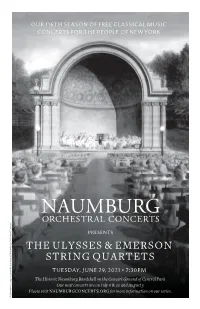

The Ulysses & Emerson String Quartets

OUR 116TH SEASON OF FREE CLASSICAL MUSIC CONCERTS FOR THE PEOPLE OF NEW YORK PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM The Historic Naumburg Bandshell on the Concert Ground of Central Park Our next concerts are on July 6 & 20 and August 3 Please visit NAUMBURGCONCERTS.ORG for more information on our series. ©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing of Naumburg Orchestral of Naumburg Concert©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM In celebration of 116 years of Free Concerts for the people of New York City - The oldest continuous free outdoor concert series in the world Tonight’s concert is being hosted by classical WQXR - 105.9 FM www.wqxr.org with WQXR host Terrance McKnight NAUMBURG ORCHESTRAL CONCERTS PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS RICHARD STRAUSS, (1864-1949) Sextet from Capriccio, Op. 85, (1942) (performed by the Ulysses Quartet with Lawrence Dutton, viola and Paul Watkins, cello) ANTON BRUCKNER, (1824-1896) String Quintet in F major, WAB 112., (1878-79) Performed by the Emerson String Quartet with Colin Brookes, viola III. Adagio, G-flat major, common time -INTERMISSION- DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH, (1906-1975) Two Pieces for String Octet, Op. 11, (1924-25) Performed with the Ulysses Quartet playing the first parts 1. Adagio 2. Allegro molto FELIX MENDELSSOHN, (1809-1847 Octet in E-flat major, Op. 20, (1825) 1. Allegro moderato ma con fuoco (E-flat major) 2. Andante (C minor) 3. Scherzo: Allegro leggierissimo (G minor) 4. Presto (E-flat major) The performance of The Ulysses and Emerson String Quartets has been made possible by a generous grant from The Arthur Loeb Foundation The summer season of 2021 honors the memory of our past President, MICHELLE R. -

A Shorter Finnegans Wake Ed. Anthony Burgess

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. A SHORTER FINNE GANS WAKE ]AMES]OYCE EDITED BY ANTHONY BURGESS NEW YORK THE VIKING PRESS "<) I \J I Foreword ASKED to name the twenty prose-works of the twentieth century most likely to survive into the twenty-first, many informed book-lovers would feel constrained to· include James Joyce's Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. I say "constrained" advisedly, because the choice of these two would rarely be as spontaneous as the choice of, say, Proust's masterpiece or a novel by D. H. Lawrence or Thomas Mann. Ulysses and Finnegans Wake are highly idiosyncratic and "difficult" books, admired more often than read, when read rarely read through to the end, when read through to the end not often fully, or even partially, under stood. This, of course, is especially t-rue of Finnegans Wake. And yet there are people who not only claim to understand a great deal of these books but affirm great love for them-love of an intensity more commonly accorded to Shakespeare or Jane Austen or Dickens. -

Modernism, Joyce, and Portuguese Literature

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 8 (2006) Issue 1 Article 5 Modernism, Joyce, and Portuguese Literature Carlos Ceia New University of Lisboa Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ceia, Carlos. "Modernism, Joyce, and Portuguese Literature." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 8.1 (2006): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1293> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 5051 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

THE THEME of CLASS in JAMES JOYCE's DUBLINERS by David

THE THEME OF CLASS IN JAMES JOYCE'S DUBLINERS by David Glyndwr Clee B.A., University of British Columbia, 1963 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of ENGLISH We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1965 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publi• cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of FJlglish The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date June k, 1965 ABSTRACT There is evidence throughout the stories, and in Joyce's letters, to show that Dubliners should be considered as a single entity rather than as a series of unconnected short stories. This thesis examines Joyce's presentation of Dublin's middle class as a unifying principle underlying the whole work. Joyce believed that his city was in the grip of a life-denying "paralysis", and this thesis studies his attempt in Dubliners to relate that paralysis to those attitudes towards experience which his Dubliners hold in c ommon. The stories in Dubliners are grouped to form a progression from childhood through adolescence to maturity and public life. -

Reimagining the Central Conflict of Joyce's Finnegans Wake

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Fall 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Fall 2020 Penman Contra Patriarch: Reimagining the Central Conflict of Joyce's Finnegans Wake Gabriel Beauregard Egset Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2020 Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Egset, Gabriel Beauregard, "Penman Contra Patriarch: Reimagining the Central Conflict of Joyce's Finnegans Wake" (2020). Senior Projects Fall 2020. 9. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2020/9 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects at Bard Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Projects Fall 2020 by an authorized administrator of Bard Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Penman Contra Patriarch Reimagining the Central Conflict of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Gabriel Egset Annandale-on-Hudson, New York December 2020 Egset 2 To my bestefar Ola Egset, we miss you dearly Egset 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 The Illustrated Penman…………………………………………………………………………………..................8 Spatial and Temporal Flesh: The Giant’s Chronotope………………………………………………….16 Cyclical Time: The Great Equalizer…………………………………………………………………………….21 The Gendered Wake Part I: Fertile Femininity…………………………………………………………...34 The Gendered Wake Part II: Sterile Masculinity…………………………………………………………39 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..54 Egset 4 Acknowledgements To my parents for their unconditional support: I love you both to the moon and back.