“Sirens” Episode of James Joyce's Ulysses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1974.Ulysses in Nighttown.Pdf

The- UNIVERSITY· THEAtl\E Present's ULYSSES .IN NIGHTTOWN By JAMES JOYCE Dramatized and Transposed by MARJORIE BARKENTIN Under the Supervision of PADRAIC COLUM Direct~ by GLENN ·cANNON Set and ~O$tume Design by RICHARD MASON Lighting Design by KENNETH ROHDE . Teehnicai.Direction by MARK BOYD \ < THE CAST . ..... .......... .. -, GLENN CANNON . ... ... ... : . ..... ·. .. : ....... ~ .......... ....... ... .. Narrator. \ JOHN HUNT . ......... .. • :.·• .. ; . ......... .. ..... : . .. : ...... Leopold Bloom. ~ . - ~ EARLL KINGSTON .. ... ·. ·. , . ,. ............. ... .... Stephen Dedalus. .. MAUREEN MULLIGAN .......... .. ... .. ......... ............ Molly Bloom . .....;. .. J.B. BELL, JR............. .•.. Idiot, Private Compton, Urchin, Voice, Clerk of the Crown and Peace, Citizen, Bloom's boy, Blacksmith, · Photographer, Male cripple; Ben Dollard, Brother .81$. ·cavalier. DIANA BERGER .......•..... :Old woman, Chifd, Pigmy woman, Old crone, Dogs, ·Mary Driscoll, Scrofulous child, Voice, Yew, Waterfall, :Sutton, Slut, Stephen's mother. ~,.. ,· ' DARYL L. CARSON .. ... ... .. Navvy, Lynch, Crier, Michael (Archbishop of Armagh), Man in macintosh, Old man, Happy Holohan, Joseph Glynn, Bloom's bodyguard. LUELLA COSTELLO .... ....... Passer~by, Zoe Higgins, Old woman. DOYAL DAVIS . ....... Simon Dedalus, Sandstrewer motorman, Philip Beau~ foy, Sir Frederick Falkiner (recorder ·of Dublin), a ~aviour and · Flagger, Old resident, Beggar, Jimmy Henry, Dr. Dixon, Professor Maginni. LESLIE ENDO . ....... ... Passer-by, Child, Crone, Bawd, Whor~. -

Letters to James Joyce

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 70 Papers of Paul and Lucie Léon (MS 34,300-34,301; 36,907-36,939) Research papers and correspondence of Paul Léon. Fashion journalism and general correspondence of Lucie Léon (or Noel). Manuscripts, inventories of materials, correspondence and miscellaneous document belonging to Paul and Lucia Léon relating to their connections with James Joyce. Compiled by Peter Kenny, Assistant Keeper Contents Introduction...............................................................................................................................3 The Papers..............................................................................................................................3 Lucie and Paul Léon...............................................................................................................3 I. Papers of Lucie Léon ...........................................................................................................5 I.i. Correspondence ................................................................................................................5 I.ii. Publications and related materials ..................................................................................6 I.iii. Biographical and miscellaneous....................................................................................8 II. Papers of Paul Léon............................................................................................................9 II.i. Research material -

Early Sources for Joyce and the New Physics: the “Wandering Rocks” Manuscript, Dora Marsden, and Magazine Culture

GENETIC JOYCE STUDIES – Issue 9 (Spring 2009) Early Sources for Joyce and the New Physics: the “Wandering Rocks” Manuscript, Dora Marsden, and Magazine Culture Jeff Drouin The bases of our physics seemed to have been put in permanently and for all time. But these bases dissolve! The hour accordingly has struck when our conceptions of physics must necessarily be overhauled. And not only these of physics. There must also ensue a reissuing of all the fundamental values. The entire question of knowledge, truth, and reality must come up for reassessment. Obviously, therefore, a new opportunity has been born for philosophy, for if there is a theory of knowledge which can support itself the effective time for its affirmation is now when all that dead weight of preconception, so overwhelming in Berkeley's time, is relieved by a transmuting sense of instability and self-mistrust appearing in those preconceptions themselves. — Dora Marsden, “Philosophy: The Science of Signs XV (continued)—Two Rival Formulas,” The Egoist (April 1918): 51. There is a substantial body of scholarship comparing James Joyce's later work with branches of contemporary physics such as the relativity theories, quantum mechanics, and wave-particle duality. Most of these studies focus on Finnegans Wake1, since it contains numerous references to Albert Einstein and also embodies the space and time debate of the mid-1920s between Joyce, Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound. There is also a fair amount of scholarship on Ulysses and physics2, which tends to compare the novel's metaphysics with those of Einstein's theories or to address the scientific content of the “Ithaca” episode. -

James Joyce – Through Film

U3A Dunedin Charitable Trust A LEARNING OPTION FOR THE RETIRED Series 2 2015 James Joyce – Through Film Dates: Tuesday 2 June to 7 July Time: 10:00 – 12:00 noon Venue: Salmond College, Knox Street, North East Valley Enrolments for this course will be limited to 55 Course Fee: $40.00 Tea and Coffee provided Course Organiser: Alan Jackson (473 6947) Course Assistant: Rosemary Hudson (477 1068) …………………………………………………………………………………… You may apply to enrol in more than one course. If you wish to do so, you must indicate your choice preferences on the application form, and include payment of the appropriate fee(s). All applications must be received by noon on Wednesday 13 May and you may expect to receive a response to your application on or about 25 May. Any questions about this course after 25 May should be referred to Jane Higham, telephone 476 1848 or on email [email protected] Please note, that from the beginning of 2015, there is to be no recording, photographing or videoing at any session in any of the courses. Please keep this brochure as a reminder of venue, dates, and times for the courses for which you apply. JAMES JOYCE – THROUGH FILM 2 June James Joyce’s Dublin – a literary biography (50 min) This documentary is an exploration of Joyce’s native city of Dublin, discovering the influences and settings for his life and work. Interviewees include Robert Nicholson (curator of the James Joyce museum), David Norris (Trinity College lecturer and Chair of the James Joyce Cultural Centre) and Ken Monaghan (Joyce’s nephew). -

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce's Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL a Thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingh

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce’s Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY English Studies School of English, Drama, American & Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham October 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis considers the imbrications created by James Joyce in his writing with the work of John Milton, through allusions, references and verbal echoes. These imbrications are analysed in light of the concept of ‘presence’, based on theories of intertextuality variously proposed by John Shawcross, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, and Eelco Runia. My analysis also deploys Gumbrecht’s concept of stimmung in order to explain how Joyce incorporates a Miltonic ‘atmosphere’ that pervades and enriches his characters and plot. By using a chronological approach, I show the subtlety of Milton’s presence in Joyce’s writing and Joyce’s strategy of weaving it into the ‘fabric’ of his works, from slight verbal echoes in Joyce’s early collection of poems, Chamber Music, to a culminating mass of Miltonic references and allusions in the multilingual Finnegans Wake. -

Ulysses: the Novel, the Author and the Translators

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 21-27, January 2011 © 2011 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.1.1.21-27 Ulysses: The Novel, the Author and the Translators Qing Wang Shandong Jiaotong University, Jinan, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—A novel of kaleidoscopic styles, Ulysses best displays James Joyce’s creativity as a renowned modernist novelist. Joyce maneuvers freely the English language to express a deep hatred for religious hypocrisy and colonizing oppressions as well as a well-masked patriotism for his motherland. In this aspect Joyce shares some similarity with his Chinese translator Xiao Qian, also a prolific writer. Index Terms—style, translation, Ulysses, James Joyce, Xiao Qian I. INTRODUCTION James Joyce (1882-1941) is regarded as one of the most innovative novelists of the 20th century. For people who are interested in modernist novels, Ulysses is an enormous aesthetic achievement. Attridge (1990, p.1) asserts that the impact of Joyce‟s literary revolution was such that “far more people read Joyce than are aware of it”, and that few later novelists “have escaped its aftershock, even when they attempt to avoid Joycean paradigms and procedures.” Gillespie and Gillespie (2000, p.1) also agree that Ulysses is “a work of art rivaled by few authors in this or any century.” Ezra Pound was one of the first to recognize the gift in Joyce. He was convinced of the greatness of Ulysses no sooner than having just read the manuscript for the first part of the novel in 1917. -

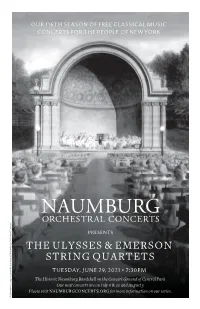

The Ulysses & Emerson String Quartets

OUR 116TH SEASON OF FREE CLASSICAL MUSIC CONCERTS FOR THE PEOPLE OF NEW YORK PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM The Historic Naumburg Bandshell on the Concert Ground of Central Park Our next concerts are on July 6 & 20 and August 3 Please visit NAUMBURGCONCERTS.ORG for more information on our series. ©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing of Naumburg Orchestral of Naumburg Concert©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM In celebration of 116 years of Free Concerts for the people of New York City - The oldest continuous free outdoor concert series in the world Tonight’s concert is being hosted by classical WQXR - 105.9 FM www.wqxr.org with WQXR host Terrance McKnight NAUMBURG ORCHESTRAL CONCERTS PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS RICHARD STRAUSS, (1864-1949) Sextet from Capriccio, Op. 85, (1942) (performed by the Ulysses Quartet with Lawrence Dutton, viola and Paul Watkins, cello) ANTON BRUCKNER, (1824-1896) String Quintet in F major, WAB 112., (1878-79) Performed by the Emerson String Quartet with Colin Brookes, viola III. Adagio, G-flat major, common time -INTERMISSION- DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH, (1906-1975) Two Pieces for String Octet, Op. 11, (1924-25) Performed with the Ulysses Quartet playing the first parts 1. Adagio 2. Allegro molto FELIX MENDELSSOHN, (1809-1847 Octet in E-flat major, Op. 20, (1825) 1. Allegro moderato ma con fuoco (E-flat major) 2. Andante (C minor) 3. Scherzo: Allegro leggierissimo (G minor) 4. Presto (E-flat major) The performance of The Ulysses and Emerson String Quartets has been made possible by a generous grant from The Arthur Loeb Foundation The summer season of 2021 honors the memory of our past President, MICHELLE R. -

A Shorter Finnegans Wake Ed. Anthony Burgess

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. A SHORTER FINNE GANS WAKE ]AMES]OYCE EDITED BY ANTHONY BURGESS NEW YORK THE VIKING PRESS "<) I \J I Foreword ASKED to name the twenty prose-works of the twentieth century most likely to survive into the twenty-first, many informed book-lovers would feel constrained to· include James Joyce's Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. I say "constrained" advisedly, because the choice of these two would rarely be as spontaneous as the choice of, say, Proust's masterpiece or a novel by D. H. Lawrence or Thomas Mann. Ulysses and Finnegans Wake are highly idiosyncratic and "difficult" books, admired more often than read, when read rarely read through to the end, when read through to the end not often fully, or even partially, under stood. This, of course, is especially t-rue of Finnegans Wake. And yet there are people who not only claim to understand a great deal of these books but affirm great love for them-love of an intensity more commonly accorded to Shakespeare or Jane Austen or Dickens. -

Harriet Shaw Weaver, Born in Frodsham in 1876, Was the Granddaughter of Edward Abbott Wright of Castle Park

Harriet in 1907 HARRIET SHAW WEAVER 1876 - 1961 Suffragist and ‘Extraordinary Woman’ Harriet Shaw Weaver, born in Frodsham in 1876, was the granddaughter of Edward Abbott Wright of Castle Park. In her time, she was both an important literary figure and a staunch supporter of women’s rights. Although Harriet was brought up in a wealthy family, she nevertheless became an active supporter of the women’s suffrage movement and eventually a member of the Communist Party. Amongst her literary circle were James Joyce, T. S. Eliot (who dedicated Selected Letters to her), Wyndham Lewis, Richard Aldington and Jean Cocteau. In 2011, Jamie Bruce Lockhart, a great nephew of Harriet Shaw Weaver, contacted Frodsham and District History Society for information on the family’s connections with Frodsham. His subsequent correspondence with the History Society’s archivist, Kath Hewitt, has provided fascinating insight into the family in which Harriet grew up and much of the information given here has resulted from this correspondence. In his book relating the story of his Cheshire relatives, Jamie fondly refers to Harriet as ‘Aunt Hat’. Early days Harriet Shaw Weaver was born at East Bank (now Fraser House), Bridge Lane, Frodsham on 1 September 1876. Her parents were Dr Frederick Poynton Weaver, and Edward Abbott Wright’s daughter, Mary Berry Wright. The Wrights had lived at Castle Park since 1861. Dr Weaver purchased East Bank in 1869 with its garden and a piece of land between the road and the railway on the opposite side of the road, plus a further piece of land beyond the railway. -

Reading the Margins of Joyce's Dubliners

Colby Quarterly Volume 18 Issue 2 June Article 6 June 1982 "Chronicles of Disorder": Reading the Margins of Joyce's Dubliners Joseph C. Voelker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 18, no.2, June 1982, p.126-144 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Voelker: "Chronicles of Disorder": Reading the Margins of Joyce's Dubliner "Chronicles of Disorder": Reading the Margins of Joyce's Dubliners by JOSEPH C. VOELKER lIKE Flaubert's Madame Bovary, Joyce's Dubliners is a book which L derives its power from ambivalence. Of the two writers, Joyce is perhaps the more generous, for while Flaubert could qualify his hatred only in the case of his heroine, Joyce found himself to be of two minds toward an entire city. All his life, Joyce oscillated between injured rage at the parochial closed-mindedness of Dublin and a grudging fondness for its inexplicable and unsteady joie de vivre. It is strange, therefore, that even sensitive readers of Dubliners have agreed to see a very singleminded Joyce lurking behind the realism of his narrative. Perhaps because of the shrillness of his letters at the time, we have come to envision the young Joyce as a nlalignant artist, crafting maledictory leitmotivs out of coffins, priests, books, and gold florins. In such a view, the book is a clinically detailed diagnosis of hemiplegia, and all conclusions concerning the quality of actions within its pages are necessarily foregone. -

Unpublished Letters of Ezra Pound to James, Nora, and Stanislaus Joyce Robert Spoo

University of Tulsa College of Law TU Law Digital Commons Articles, Chapters in Books and Other Contributions to Scholarly Works 1995 Unpublished Letters of Ezra Pound to James, Nora, and Stanislaus Joyce Robert Spoo Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/fac_pub Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation 32 James Joyce Q. 533-81 (1995). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles, Chapters in Books and Other Contributions to Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unpublished Letters of Ezra Pound to James, Nora, and Stanislaus Joyce Robert Spoo University of Tulsa According to my computation, 198 letters between Ezra so come Pound and James Joyce have far to light. Excluding or letters to by family members (as when Joyce had Nora write for him during his iUnesses), I count 103 letters by Joyce to Pound, 26 of which have been pubUshed, and 95 letters by Pound to Joyce, 75 of which have been published. These numbers should give some idea of the service that Forrest Read performed nearly thirty years ago in collecting and pubUshing the letters of Pound to Joyce,1 and make vividly clear also how poorly represented in print Joyce's side of the correspondence is. Given the present policy of the Estate of James Joyce, we cannot expect to see this imbalance rectified any time soon, but Iwould remind readers that the bulk of Joyce's un pubUshed letters to Pound may be examined at Yale University's Beinecke Library. -

Thesis-1996D-B786j.Pdf (6.977Mb)

JAMES JOYCE AND THE DARWINIAN IMAGINATION By PAUL ALAN BOWERS Bachelor of Arts The University of Tulsa Tulsa, Oklahoma 1985 Master of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1990 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 1996 JAMES JOYCE AND THE DARWINIAN IMAGINATION Thesis Approved: I . I ---1 -. Lr*· Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Edward P. Walkiewicz, not only for his invaluable intellectual contributions to this project, but also for his unwavering enthusiasm shown during our numerous conversations. Without his support, this study would never have come to fruition. I also extend my sincere thanks to the members of my doctoral committee, namely, Dr. Linda Austin, Dr. Doren Recker, Dr. Martin Wallen, and Dr. Elizabeth Grubgeld. To Elizabeth Grubgeld, I offer a special note of appreciation for her constant encouragement and kindness during my years at OSU. I would be remiss if I failed to acknowledge the support of certain individuals I have had the pleasure to study and work with over the last several years. To these friends and colleagues, I owe a great debt: Dr. Jeffrey Walker, Dr. Gordon Weaver, Dr. Al Learst, Dr. Darin Cozzens, Jules Emig, Shirley Bechtel, and Kim Marotta. Lastly, I acknowledge my indebtedness to my wife, Denise, who has endured much during the completion of this project, but always with perfect kindness iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page INTRODUCTION: IN THE MOST LIKELY OF PLACES .