The Tympanic Region of the Mammalian Skull by P. N. Van Kampen*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V. -

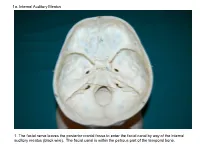

1A. Internal Auditory Meatus

1a. Internal Auditory Meatus 1. The facial nerve leaves the posterior cranial fossa to enter the facial canal by way of the internal auditory meatus (black wire). The facial canal is within the petrous part of the temporal bone. 1b. Internal Auditory Meatus The facial nerve leaves the posterior cranial fossa to enter the facial canal by way of the internal auditory meatus (black wire). 2. Hiatus of the Canal and Groove for the Greater Superficial Petrosal Nerve The greater superficial petrosal nerve leaves the facial canal to enter the middle cranial fossa by way of the hiatus of the canal for the greater superficial petrosal nerve (black wire). 3. Pterygoid Canal at Anterior Lip of the Lacerate Foramen The greater superficial petrosal nerve is joined by the deep petrosal nerve to form the nerve of the pterygoid canal (black and red wire). This nerve leaves the middle cranial fossa to enter the pterygopalatine fossa by way of the pterygoid canal. The posterior opening of the pterygoid canal is at the anterior lip of the lacerate foramen. The greater superficial nerve and the deep petrosal nerve travel within the cavernous sinus. 4. Pterygopalatine Fossa Seen Through the Pterygomaxillary Fissure The anterior opening of the pterygoid canal is into the pterygopalatine fossa (black wire). The pterygopalatine fossa is located medial to the pterygomaxillary fissure and contains the pterygopalatine ganglion. 5. External Auditory Meatus The chorda tympani nerve leaves the facial canal and crosses the middle ear (black wire). It then leaves the middle ear to arrive in the infratemporal fossa by way of the petrotympanic fissure. -

Dissection and Exposure of the Whole Course of Deep Nerves in Human Head Specimens After Decalcification

Hindawi Publishing Corporation International Journal of Otolaryngology Volume 2012, Article ID 418650, 7 pages doi:10.1155/2012/418650 Research Article Dissection and Exposure of the Whole Course of Deep Nerves in Human Head Specimens after Decalcification Longping Liu, Robin Arnold, and Marcus Robinson Discipline of Anatomy and Histology, University of Sydney, Anderson Stuart Building F13, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Correspondence should be addressed to Marcus Robinson, [email protected] Received 29 July 2011; Revised 10 November 2011; Accepted 12 December 2011 AcademicEditor:R.L.Doty Copyright © 2012 Longping Liu et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The whole course of the chorda tympani nerve, nerve of pterygoid canal, and facial nerves and their relationships with surrounding structures are complex. After reviewing the literature, it was found that details of the whole course of these deep nerves are rarely reported and specimens displaying these nerves are rarely seen in the dissecting room, anatomical museum, or atlases. Dissections were performed on 16 decalcified human head specimens, exposing the chorda tympani and the nerve connection between the geniculate and pterygopalatine ganglia. Measurements of nerve lengths, branching distances, and ganglia size were taken. The chorda tympani is a very fine nerve (0.44 mm in diameter within the tympanic cavity) and approximately 54 mm in length. The mean length of the facial nerve from opening of internal acoustic meatus to stylomastoid foramen was 52.5 mm. -

Os Temporale (Halántékcsont)

CRANIOFACIAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL ASPECTS OF THE SKULL PhD., Dr. Dávid Lendvai / Dr. Gábor Baksa Semmelweis University Anatomy, Histology and Embryogy Institute Budapest 2018 MAIN PARTS OF THE SKULL •Constitute by 22 bones: •neurocranium (8) – UNPAIRED: frontal, occipital, sphenoid, ethmoid bones PAIRED: temporal, parietal bones •viscerocranium (14) -UNPAIRED: mandibule, vomer. PAIRED: nasal, maxilla, zygomatic, lacrimal, palatine, inferior nasal concha Their role – formation of cavities, protect viscera, voice formation, initial portions of the gastrointerstinal and respiratory systems, insertion of muscles (mascication, head movements) Cavities: - Cranial cavity, - Nasal cavity, - Paranasal sinuses - Oral cavity, - Orbit, - (Tympanic cavity, Inner ear) Cranium cerebrale 1. calvaria 2. Skull base: •Basis cranii int. •Basis cranii ext. Protub. occip. ext. → linea nuchae sup. → beginning of the linea temp. → zygomatic arch → infratemp. crest → ala major → zygomatic process → supraorbital margin → nasofrontalis suture External skull base Braus Internal skull base Braus Why do we need the neuroanatomy? Picture: Peter Claesz – Vanitas (still-life, 1630.) www.hydrocephalus.inf o ? www.totalhealth.co.u k Aesculap - B Braun Todoro w Physiologically volume and pressure are balanced within the skull A minimally disturbed balance can be already compensated Over the normal range of this compensation ability minimal changes in the volume lead to a disproportionally high elevation of intracranial pressure (ICP) (for further see in physiology the Monroe -

Inferior View of Skull

human anatomy 2016 lecture sixth Dr meethak ali ahmed neurosurgeon Inferior View Of Skull the anterior part of this aspect of skull is seen to be formed by the hard palate.The palatal process of the maxilla and horizontal plate of the palatine bones can be identified . in the midline anteriorly is the incisive fossa & foramen . posterolaterlly are greater & lesser palatine foramena. Above the posterior edge of the hard palate are the choanae(posterior nasal apertures ) . these are separated from each other by the posterior margin of the vomer & bounded laterally by the medial pterygoid plate of sphenoid bone . the inferior end of the medial pterygoid plate is prolonged as a curved spike of bone , the pterygoid hamulus. the superior end widens to form the scaphoid fossa . posterolateral to the lateral pterygoid plate the greater wing of the sphenoid is pieced by the large foramen ovale & small foramen spinosum . posterolateral to the foramen spinosum is spine of the sphenoid . Above the medial border of the scaphoid fossa , the sphenoid bone is pierced by pterygoid canal . Behind the spine of the sphenoid , in the interval between the greater wing of the sphenoid and the petrous part of the temporal bone , there is agroove for the cartilaginous part of the auditory tube. The opening of the bony part of the tube can be identified. The mandibular fossa of the temporal bone & the articular tubercle form the upper articular surfaces for the temporomandibular joint . separating the mandibular fossa from the tympanic plate posteriorly is the squamotympanic fissure, through the medial end of which (petrotympanic fissure ) the chorda tympani exits from the tympanic cavity .The styloid process of the temporal bone projects downward & forward from its inferior aspect. -

Skull / Cranium

Important! 1. Memorizing these pages only does not guarantee the succesfull passing of the midterm test or the semifinal exam. 2. The handout has not been supervised, and I can not guarantee, that these pages are absolutely free from mistakes. If you find any, please, report to me! SKULL / CRANIUM BONES OF THE NEUROCRANIUM (7) Occipital bone (1) Sphenoid bone (1) Temporal bone (2) Frontal bone (1) Parietal bone (2) BONES OF THE VISCEROCRANIUM (15) Ethmoid bone (1) Maxilla (2) Mandible (1) Zygomatic bone (2) Nasal bone (2) Lacrimal bone (2) Inferior nasalis concha (2) Vomer (1) Palatine bone (2) Compiled by: Dr. Czigner Andrea 1 FRONTAL BONE MAIN PARTS: FRONTAL SQUAMA ORBITAL PARTS NASAL PART FRONTAL SQUAMA Parietal margin Sphenoid margin Supraorbital margin External surface Frontal tubercle Temporal surface Superciliary arch Zygomatic process Glabella Supraorbital margin Frontal notch Supraorbital foramen Internal surface Frontal crest Sulcus for superior sagittal sinus Foramen caecum ORBITAL PARTS Ethmoidal notch Cerebral surface impresiones digitatae Orbital surface Fossa for lacrimal gland Trochlear notch / fovea Anterior ethmoidal foramen Posterior ethmoidal foramen NASAL PART nasal spine nasal margin frontal sinus Compiled by: Dr. Czigner Andrea 2 SPHENOID BONE MAIN PARTS: CORPUS / BODY GREATER WINGS LESSER WINGS PTERYGOID PROCESSES CORPUS / BODY Sphenoid sinus Septum of sphenoid sinus Sphenoidal crest Sphenoidal concha Apertura sinus sphenoidalis / Opening of sphenoid sinus Sella turcica Hypophyseal fossa Dorsum sellae Posterior clinoid process Praechiasmatic sulcus Carotid sulcus GREATER WINGS Cerebral surface • Foramen rotundum • Framen ovale • Foramen spinosum Temporal surface Infratemporalis crest Infratemporal surface Orbital surface Maxillary surface LESSER WINGS Anterior clinoid process Superior orbital fissure Optic canal PTERYGOID PROCESSES Lateral plate Medial plate Pterygoid hamulus Pterygoid fossa Pterygoid sulcus Scaphoid fossa Pterygoid notch Pterygoid canal (Vidian canal) Compiled by: Dr. -

Spring Quarter Lawrence M. Witmer, Phd Life Sciences Building, Room 123

Skull PCC I: Spring Quarter Lawrence M. Witmer, PhD Life Sciences Building, Room 123 READINGS: Moore & Dalley’s text: 832–850; Moore & Persaud’s Embryology text: 414–419, 216–230 LAB READING: Dissector: 221–223; this handout provides the major source for the lab reading— BRING THIS HANDOUT TO LAB I. General Terms A. Skull: may or may not include mandible (i.e., sources vary) B. Cranium (= neurocranium): that part enclosing the brain 1. Calvaria: superior part 2. Cranial base (= basicranium): inferior part 3. Includes: parietals, temporals, frontal, occipital, sphenoid, ethmoid 4. Calotte: the “skull cap” sawed off for autopsies & dissection C. Facial skeleton 1. The rest of the head skeleton 2. Includes: maxillae, zygomatics, palatines, lacrimals, nasals, inferior nasal conchae, vomer, ethmoid, mandible D. Sutures: junctures between the individual skull bones II. Embryology & Development A. Organization 1. Portions of the skull a. Neurocranium: surrounding the brain b. Viscerocranium: the jaw apparatus and associated structures 2. Types of ossification a. Endochondral ossification: bones are ossified from cartilaginous precursors b. Intramembranous ossification: bones are ossified directly from mesenchyme investing various structures (e.g., the brain, cartilaginous structures) B. Developmental origins of the skull 1. Cartilaginous neurocranium (= chondrocranium) a. Forms from fusion of several primordial cartilages b. Forms structures in skull base via endochondral ossification Witmer – Skull – Spring Quarter – 1 c. Adult bones: occipital, petromastoid part of temporal bone, sphenoid, ethmoid 2. Membranous neurocranium a. Forms bones around the brain via intramembranous ossification b. Adult bones: frontal, parietal 3. Cartilaginous viscerocranium a. Forms from the cartilages of the first two branchial arches via endochondral ossification b. -

Tympanic Plate Fractures in Temporal Bone Trauma: Prevalence and Associated Injuries

ORIGINAL RESEARCH HEAD & NECK Tympanic Plate Fractures in Temporal Bone Trauma: Prevalence and Associated Injuries C.P. Wood, C.H. Hunt, D.C. Bergen, M.L. Carlson, F.E. Diehn, K.M. Schwartz, G.A. McKenzie, R.F. Morreale, and J.I. Lane ABSTRACT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: The prevalence of tympanic plate fractures, which are associated with an increased risk of external auditory canal stenosis following temporal bone trauma, is unknown. A review of posttraumatic high-resolution CT temporal bone examinations was performed to determine the prevalence of tympanic plate fractures and to identify any associated temporal bone injuries. MATERIALS AND METHODS: A retrospective review was performed to evaluate patients with head trauma who underwent emergent high-resolution CT examinations of the temporal bone from July 2006 to March 2012. Fractures were identified and assessed for orienta- tion; involvement of the tympanic plate, scutum, bony labyrinth, facial nerve canal, and temporomandibular joint; and ossicular chain disruption. RESULTS: Thirty-nine patients (41.3 Ϯ 17.2 years of age) had a total of 46 temporal bone fractures (7 bilateral). Tympanic plate fractures were identified in 27 (58.7%) of these 46 fractures. Ossicular disruption occurred in 17 (37.0%). Fractures involving the scutum occurred in 25 (54.4%). None of the 46 fractured temporal bones had a mandibular condyle dislocation or fracture. Of the 27 cases of tympanic plate fractures, 14 (51.8%) had ossicular disruption (P ϭ .016) and 18 (66.6%) had a fracture of the scutum (P ϭ .044). Temporomandibular joint gas was seen in 15 (33%) but was not statistically associated with tympanic plate fracture (P ϭ .21). -

Video Review of Foramina (Openings) at Base of Skull

VIDEO REVIEW OF FORAMINA (OPENINGS) AT BASE OF SKULL 1- Base of the skull is the roof of the mouth 2- Cranial nerves VII, IX, X, XI and XII leave by foramina at the base of the skull. 3- Arteries to the brain enter the cranial cavity via the base of skull. 4- Summary slide at end. FORAMINA LANDMARKS INCISIVE FORAMEN GREATER LATERAL AND PALATINE MEDIAL (with FORAMEN Hamulus) PTERYGOID LESSER PALATINE PLATES FORAMEN FORAMEN OVALE EXTERNAL AUDITORY FORAMEN SPINOSUM MEATUS CAROTID CANAL STYLOMASTOID FORAMEN MASTOID PROCESS JUGULAR FORAMEN OCCIPITAL HYPOGLOSSAL CANAL CONDYLES FORAMEN MAGNUM HARD PALATE - LANDMARKS OF 1) MAXILLARY BONES BASE OF SKULL 2) PALATINE BONES HAMULUS of MEDIAL MEDIAL AND PTERYGOID LATERAL PLATE PTERYGOID PLATES OF SPHENOID BONE EXTERNAL AUDITORY MEATUS OCCIPITAL FORAMEN CONDYLES MAGNUM OPENINGS IN INCISIVE FORAMEN - PALATE NASOPALATINE N. (V2), SPHENO- PALATINE ARTERY GREATER PALATINE FORAMEN - GREATER PALATINE N. (V2) AND ARTERY LESSER PALATINE FORAMEN - LESSER PALATINE N. (V2) AND ARTERY NASAL CAVITY SPHENO- PALATINE FORAMEN - SPHENOPALATINE ARTERY, NASOPALATINE NERVE (V2) SPHENO- PALATINE FORAMEN - SPHENOPALATINE ARTERY, NASOPALATINE NERVE (V2) Photo: Thanks to Danny McNeil, JCESOM 2013 LOOK FOR LATERAL OPENINGS TO MIDDLE PTERYGOID CRANIAL FOSSA PLATE FORAMEN OVALE - V3, ACCESSORY MENINGEAL ARTERY FORAMEN SPINOSUM - MIDDLE MENINGEAL ARTERY, NERVUS SPINOSUS ARTERIES TO BRAIN CAROTID CANAL: LOOK ENTER AT BASE MEDIAL TO EXTERNAL OF SKULL AUDITORY MEATUS CAROTID CANAL – (OPENS TO FORAMEN LACERUM INSIDE MIDDLE CRANIAL -

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

Regions of the Head 9. Oral Cavity & Perioral Regions Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Zygomatic process of temporal bone Articular tubercle Mandibular Petrotympanic fossa of TMJ fissure Postglenoid tubercle Styloid process External acoustic meatus Mastoid process (auditory canal) Atlanto- occipital joint Fig. 9.27 Mandibular fossa of the TMJ tubercle. Unlike other articular surfaces, the mandibular fossa is cov- Inferior view of skull base. The head (condyle) of the mandible artic- ered by fi brocartilage, not hyaline cartilage. As a result, it is not as ulates with the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone via an articu- clearly delineated on the skull (compare to the atlanto-occipital joints). lar disk. The mandibular fossa is a depression in the squamous part of The external auditory canal lies just posterior to the mandibular fossa. the temporal bone, bounded by an articular tubercle and a postglenoid Trauma to the mandible may damage the auditory canal. Head (condyle) of mandible Pterygoid Joint fovea capsule Neck of Coronoid mandible Lateral process ligament Neck of mandible Lingula Mandibular Stylomandibular foramen ligament Mylohyoid groove AB Fig. 9.28 Head of the mandible in the TMJ Fig. 9.29 Ligaments of the lateral TMJ A Anterior view. B Posterior view. The head (condyle) of the mandible is Left lateral view. The TMJ is surrounded by a relatively lax capsule that markedly smaller than the mandibular fossa and has a cylindrical shape. permits physiological dislocation during jaw opening. The joint is stabi- Both factors increase the mobility of the mandibular head, allowing lized by three ligaments: lateral, stylomandibular, and sphenomandib- rotational movements about a vertical axis. -

An Investigation of the Morphology of the Petrotympanic Fissure Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography

JOURNAL OF ORAL & MAXILLOFACIAL RESEARCH Damaskos et al. An Investigation of the Morphology of the Petrotympanic Fissure Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Spyros Damaskos1,2, Konstantinos Syriopoulos3,4, Rogier L. Sens3,4, Constantinus Politis3,4 1Department of Oral Radiology, Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2Department of Oral Diagnosis and Radiology, School of Dentistry, NKUA, Athens, Greece. 3Department of Imaging and Pathology, OMFS IMPATH Research Group, Faculty of Medicine, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium. 4Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium. Corresponding Author: Spyros Damaskos Department of Oral Radiology Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA) Gustav Mahler Laan 3004, 1081 LA, Amsterdam The Netherlands Phone: +30 6944 541529 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT Objectives: The purpose of the present study was: a) to examine the visibility and morphology of the petrotympanic fissure on cone-beam computed tomography images, and b) to investigate whether the petrotympanic fissure morphology is significantly affected by gender and age, or not. Material and Methods: Using Newtom VGi (QR Verona, Italy), 106 cone-beam computed tomography examinations (212 temporomandibular joint areas) of both genders were retrospectively and randomly selected. Two observers examined the images and subsequently classified by consensus the petrotympanic fissure morphology into the following three types: type 1 - widely open; type 2 - narrow middle; type 3 - very narrow/closed. Results: The petrotympanic fissure morphology was assessed as type 1, type 2, and type 3 in 85 (40.1%), 72 (34.0%), and 55 (25.9%) cases, respectively. No significant difference was found between left and right petrotympanic fissure morphology (Kappa = 0.37; P < 0.001). -

Anatomical Causes of Costen's Syndrome

Research Article Anatomical causes of Costen’s syndrome Ivan V. Gaivoronskiy1, Alexander V. Tscymbalystov2, Maria G. Gaivoronskaya3*, Irina V. Voytyatskaya2, Vladimir K. Leontiev2, Sergey Y Ivanov2 ABSTRACT On 108 skulls specimens with malocclusion and 30 skulls specimens with complete edentulism from the craniological collection of the Department of Normal Anatomy of the Military Medical Academy named after S.M. Kirov, a comprehensive study of the morphometric characteristics of the articular surfaces of TMD joint was carried out. The peculiarities of petrotympanic fissure topography in various forms of the brain skull were also evaluated to establish the possible anatomical causes of Costen’s syndrome. The fact of the variability of the petrotympanic fissure topography within the mandibular fossa has been established, the fissure can be located in back and mesial parts of this fossa or it takes intermediate position. The option of petrotympanic fissure topography in mesial parts of the mandibular fossa is a predisposing anatomical factor for Costen’s syndrome and can be found at different neurocranium forms but predominantly at hypsicranial. The immediate cause of the Costen’s syndrome can be occlusal-caused diseases followed by TMD joint dysfunction. In this case, the changes of articular surface of TMD joint take place, in particular, a decrease in size of the head of mandible, its pathological displace, capsule stretching, and compression of chorda tympani. KEY WORDS: Articular head, Brain skull, Chorda tympani, Costen’s syndrome, Dysfunction, Mandibular fossa, Petrotympanic fissure, Temporomandibular joint INTRODUCTION of the tongue, and dull ache in the ears, eyes, etc., is defined as one of the symptoms of TMJ dysfunction.