Comparative Cranial Anatomy of Rattus Norvegicus and Proechimys Trinitatus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socioeconomic and Ecological Aspects of Field Rat Control in Tropical and Subtropical Countries Bans Kurylas

SOCIOECONOMIC AND ECOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF FIELD RAT CONTROL IN TROPICAL AND SUBTROPICAL COUNTRIES BANS KURYLAS. Thai-German Rodent Control Project. German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ), P.O. Box 9-34, Bangkok. Thailand. ABSTRACT: The vital question. as to the cause of the pennanent increase in field rat populations throughout most tropical and subtropical areas. has been the subject of researchers and fielcM!en during the past years, in the hope of finding an answer to this problem. Man has made his way through history wherein he was gradually able to renounce nature and establish his own man-made cultural frame. Unlike other marrmals. man has no natural instincts to guide him through life. Brain and spirit have to compensate for lack of. physical capabilities and instincts. Man was forced to change his natural surroundings in order to serve his special and ever-growing needs . Survival meant not only using nature but more so changing it in order to develop his culture. The field rat has become man's "cultural treader"! Myomorpha is the largest suborder of the Order Rodentia. Of the 1700 rodents known to man. more than 1100 belong to this group. The greater part of the Myomorpha species are found within two families, which are Cricetidae with about 567 species and Muridae with about 475 species. Most of these rodents live either in trees or under the ground. They rarely collide with man's interest. Only a few rodent species have become "field rats" and seem to dwell in and utilize man's cultural steppe. Some species have even become cosmopolitan and are found in Europe. -

The Morphometric Study of Occurrence and Variations of Foramen Ovale S

Research Article The morphometric study of occurrence and variations of foramen ovale S. Ajrish George*, M. S. Thenmozhi ABSTRACT Background: Foramen vale is one of the important foramina present in the sphenoid bone. Anatomically it is located in the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The foramen ovale is situated posterolateral to the foramen rotundum and anteromedial to the foramen spinosum. The foramen spinosum is present posterior to the foramen ovale. The carotid canal is present posterior and medial to the foramen spinosum and the foramen rotundum is present anterior to the foramen ovale. The structures which pass through the foramen ovale are the mandibular nerve, emissary vein, accessory middle meningeal artery, and lesser petrosal nerve. The sphenoid bone has a body, a pair of greater wing, pair of lesser wing, pair of lateral pterygoid plate, and a pair of medial pterygoid plate. Aim: The study involves the assessment of any additional features in foramen ovale in dry South Indian skulls. Materials and Methods: This study involves examination of dry adult skulls. First, the foramen ovale is located, and then it is carefully examined for presence of alterations and additional features, and is recorded following computing the data and analyzing it. Results: The maximum length of foramen ovale on the right and left was 10.1 mm, 4.3 mm, respectively. The minimum length of the foramen in right and left was 9.1 mm, 3.2 mm, respectively. The maximum width of foramen ovale on the right and left was 4.8 mm and 2.3 mm, respectively. The minimum width of the foramen in the right and the left side was 5.7 mm and 2.9 mm, respectively. -

Learning About Mammals

Learning About Mammals The mammals (Class Mammalia) includes everything from mice to elephants, bats to whales and, of course, man. The amazing diversity of mammals is what has allowed them to live in any habitat from desert to arctic to the deep ocean. They live in trees, they live on the ground, they live underground, and in caves. Some are active during the day (diurnal), while some are active at night (nocturnal) and some are just active at dawn and dusk (crepuscular). They live alone (solitary) or in great herds (gregarious). They mate for life (monogamous) or form harems (polygamous). They eat meat (carnivores), they eat plants (herbivores) and they eat both (omnivores). They fill every niche imaginable. Mammals come in all shapes and sizes from the tiny pygmy shrew, weighing 1/10 of an ounce (2.8 grams), to the blue whale, weighing more than 300,000 pounds! They have a huge variation in life span from a small rodent living one year to an elephant living 70 years. Generally, the bigger the mammal, the longer the life span, except for bats, which are as small as rodents, but can live for up to 20 years. Though huge variation exists in mammals, there are a few physical traits that unite them. 1) Mammals are covered with body hair (fur). Though marine mammals, like dolphins and whales, have traded the benefits of body hair for better aerodynamics for traveling in water, they do still have some bristly hair on their faces (and embryonically - before birth). Hair is important for keeping mammals warm in cold climates, protecting them from sunburn and scratches, and used to warn off others, like when a dog raises the hair on its neck. -

Gross Anatomy Assignment Name: Olorunfemi Peace Toluwalase Matric No: 17/Mhs01/257 Dept: Mbbs Course: Gross Anatomy of Head and Neck

GROSS ANATOMY ASSIGNMENT NAME: OLORUNFEMI PEACE TOLUWALASE MATRIC NO: 17/MHS01/257 DEPT: MBBS COURSE: GROSS ANATOMY OF HEAD AND NECK QUESTION 1 Write an essay on the carvernous sinus. The cavernous sinuses are one of several drainage pathways for the brain that sits in the middle. In addition to receiving venous drainage from the brain, it also receives tributaries from parts of the face. STRUCTURE ➢ The cavernous sinuses are 1 cm wide cavities that extend a distance of 2 cm from the most posterior aspect of the orbit to the petrous part of the temporal bone. ➢ They are bilaterally paired collections of venous plexuses that sit on either side of the sphenoid bone. ➢ Although they are not truly trabeculated cavities like the corpora cavernosa of the penis, the numerous plexuses, however, give the cavities their characteristic sponge-like appearance. ➢ The cavernous sinus is roofed by an inner layer of dura matter that continues with the diaphragma sellae that covers the superior part of the pituitary gland. The roof of the sinus also has several other attachments. ➢ Anteriorly, it attaches to the anterior and middle clinoid processes, posteriorly it attaches to the tentorium (at its attachment to the posterior clinoid process). Part of the periosteum of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone forms the floor of the sinus. ➢ The body of the sphenoid acts as the medial wall of the sinus while the lateral wall is formed from the visceral part of the dura mater. CONTENTS The cavernous sinus contains the internal carotid artery and several cranial nerves. Abducens nerve (CN VI) traverses the sinus lateral to the internal carotid artery. -

Hystrix Africaeaustralis)

Reproduction in captive female Cape porcupines (Hystrix africaeaustralis) R. J. van Aarde Mammal Research Institute, University ofPretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa Summary. Captive females attained sexual maturity at an age of 9\p=n-\16months and con- ceived for the first time when 10\p=n-\25months old. Adult females were polyoestrous but did not cycle while lactating or when isolated from males. The length of the cycle varied from 17 to 42 days (mean \m=+-\s.d. 31\m=.\2\m=+-\6\m=.\5days; n = 43) and females experienced 3\p=n-\7 sterile cycles before conceiving. Pregnancy lasted for 93\p=n-\94days (93\m=.\5\m=+-\0\m=.\6days; N = 4) and litter intervals varied from 296 to 500 days (385 \m=+-\60\m=.\4;n = 10). Litter size varied from 1 to 3 (1\m=.\5\m=+-\0\m=.\66;n = 165) and the well-developed precocial young weighed 300\p=n-\400g (351 \m=+-\47\m=.\4g; n= 19) at birth. Captive females reproduced throughout the year with most litters (78\m=.\7%;n = 165) being produced between August and March. Introduction Cape porcupines (Hystrix africaeaustralis) inhabit tropical forests, woodlands, grassland savannas, semi-arid and arid environments throughout southern Africa. Despite this widespread distribution little attention has been given to these nocturnal, Old World hystricomorph rodents, which shelter and breed in subterranean burrows, rock crevices and caves. Some information on reproduction in female porcupines has been published on the crested porcupine (H. cristata) (Weir, 1967), the Himalayan porcupine (H. hodgsoni) (Gosling, 1980) and the Indian porcupine (H. -

Branches of the Maxillary Artery of the Domestic

Table 4.2: Branches of the Maxillary Artery of the Domestic Pig, Sus scrofa Artery Origin Course Distribution Departs superficial aspect of MA immediately distal to the caudal auricular. Course is typical, with a conserved branching pattern for major distributing tributaries: the Facial and masseteric regions via Superficial masseteric and transverse facial arteries originate low in the the masseteric and transverse facial MA Temporal Artery course of the STA. The remainder of the vessel is straight and arteries; temporalis muscle; largely unbranching-- most of the smaller rami are anterior auricle. concentrated in the proximal portion of the vessel. The STA terminates in the anterior wall of the auricle. Originates from the lateral surface of the proximal STA posterior to the condylar process. Hooks around mandibular Transverse Facial Parotid gland, caudal border of the STA ramus and parotid gland to distribute across the masseter Artery masseter muscle. muscle. Relative to the TFA of Camelids, the suid TFA has a truncated distribution. From ventral surface of MA, numerous pterygoid branches Pterygoid Branches MA Pterygoideus muscles. supply medial and lateral pterygoideus muscles. Caudal Deep MA Arises from superior surface of MA; gives off masseteric a. Deep surface of temporalis muscle. Temporal Artery Short course deep to zygomatic arch. Contacts the deep Caudal Deep Deep surface of the masseteric Masseteric Artery surface of the masseter between the coronoid and condylar Temporal Artery muscle. processes of the mandible. Artery Origin Course Distribution Compensates for distribution of facial artery. It should be noted that One of the larger tributaries of the MA. Originates in the this vessel does not terminate as sphenopalatine fossa as almost a terminal bifurcation of the mandibular and maxillary labial MA; lateral branch continuing as buccal and medial branch arteries. -

The Beaver's Phylogenetic Lineage Illuminated by Retroposon Reads

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The Beaver’s Phylogenetic Lineage Illuminated by Retroposon Reads Liliya Doronina1,*, Andreas Matzke1,*, Gennady Churakov1,2, Monika Stoll3, Andreas Huge3 & Jürgen Schmitz1 Received: 13 October 2016 Solving problematic phylogenetic relationships often requires high quality genome data. However, Accepted: 25 January 2017 for many organisms such data are still not available. Among rodents, the phylogenetic position of the Published: 03 March 2017 beaver has always attracted special interest. The arrangement of the beaver’s masseter (jaw-closer) muscle once suggested a strong affinity to some sciurid rodents (e.g., squirrels), placing them in the Sciuromorpha suborder. Modern molecular data, however, suggested a closer relationship of beaver to the representatives of the mouse-related clade, but significant data from virtually homoplasy- free markers (for example retroposon insertions) for the exact position of the beaver have not been available. We derived a gross genome assembly from deposited genomic Illumina paired-end reads and extracted thousands of potential phylogenetically informative retroposon markers using the new bioinformatics coordinate extractor fastCOEX, enabling us to evaluate different hypotheses for the phylogenetic position of the beaver. Comparative results provided significant support for a clear relationship between beavers (Castoridae) and kangaroo rat-related species (Geomyoidea) (p < 0.0015, six markers, no conflicting data) within a significantly supported mouse-related clade (including Myodonta, Anomaluromorpha, and Castorimorpha) (p < 0.0015, six markers, no conflicting data). Most of an organism’s phylogenetic history is fossilized in their heritable genomic material. Using data from genome sequencing projects, particularly informative regions of this material can be extracted in sufficient num- bers to resolve the deepest history of speciation. -

Septation of the Sphenoid Sinus and Its Clinical Significance

1793 International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health Septation of the Sphenoid Sinus and its Clinical Significance Eldan Kapur 1* , Adnan Kapidžić 2, Amela Kulenović 1, Lana Sarajlić 2, Adis Šahinović 2, Maida Šahinović 3 1 Department of anatomy, Medical faculty, University of Sarajevo, Čekaluša 90, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2 Clinic for otorhinolaryngology, Clinical centre University of Sarajevo, Bolnička 25, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina 3 Department of histology and embriology, Medical faculty, University of Sarajevo, Čekaluša 90, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina * Corresponding Author: Eldan Kapur, MD, PhD Department of anatomy, Medical faculty, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Email: [email protected] Phone: 033 66 55 49; 033 22 64 78 (ext. 136) Abstract Introduction: Sphenoid sinus is located in the body of sphenoid, closed with a thin plate of bone tissue that separates it from the important structures such as the optic nerve, optic chiasm, cavernous sinus, pituitary gland, and internal carotid artery. It is divided by one or more vertical septa that are often asymmetric. Because of its location and the relationships with important neurovascular and glandular structures, sphenoid sinus represents a great diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Aim: The aim of this study was to assess the septation of the sphenoid sinus and relationship between the number and position of septa and internal carotid artery in the adult BH population. Participants and Methods: A retrospective study of the CT analysis of the paranasal sinuses in 200 patients (104 male, 96 female) were performed using Siemens Somatom Art with the following parameters: 130 mAs: 120 kV, Slice: 3 mm. -

Morphometry of Parietal Foramen in Skulls of Telangana Population Dr

Scholars International Journal of Anatomy and Physiology Abbreviated Key Title: Sch Int J Anat Physiol ISSN 2616-8618 (Print) |ISSN 2617-345X (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: https://saudijournals.com/sijap Original Research Article Morphometry of Parietal Foramen in Skulls of Telangana Population Dr. T. Sumalatha1, Dr. V. Sailaja2*, Dr. S. Deepthi3, Dr. Mounica Katukuri4 1Associate professor, Department of Anatomy, Government Medical College, Mahabubnagar, Telangana, India 2Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy, Gandhi Medical College, Secunderabad, Telangana, India 3Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy, Government Medical College, Mahabubnagar, Telangana, India 4Post Graduate 2nd year, Gandhi Medical College, Secunderabad, Telangana, India DOI: 10.36348/sijap.2020.v03i10.001 | Received: 06.10.2020 | Accepted: 14.10.2020 | Published: 18.10.2020 *Corresponding author: Dr. V. Sailaja Abstract Aims & Objectives: To study the prevalence, number, location and variations of parietal foramen in human skulls and correlate with the clinical significance if any. Material and Methods: A total of 45 skulls with 90 parietal bones were studied in the Department of Anatomy Govt medical college Mahabubnagar from osteology specimens in the academic year 2018-2019.Various parameters like unilateral or bilateral occurance or total absence of the parietal foramen, their location in relation to sagittal suture and lambda, their shape have been observed using appropriate tools and the findings have been tabulate. Observation & Conclusions: Out of total 45 skulls there were 64 parietal foramina in 90 parietal bones, with foramina only on right side in 10 skulls, only on left side in 7 skulls, bilaterally present in 23 skulls, total absence in 4 skulls and 1 foramen located in the sagittal suture. -

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V. -

Clinical Importance of the Middle Meningeal Artery

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository FOLIA MEDICA CRACOVIENSIA 41 Vol. LIII, 1, 2013: 41–46 PL ISSN 0015-5616 Przemysław Chmielewski1, Janusz skrzat1, Jerzy waloCha1 CLINICAL IMPORTANCE OF THE MIDDLE MENINGEAL ARTERY Abstract: Middle meningeal artery (MMA)is an important branch which supplies among others cranial dura mater. It directly attaches to the cranial bones (is incorporated into periosteal layer of dura mater), favors common injuries in course of head trauma. This review describes available data on the MMA considering its varability, or treats specific diseases or injuries where the course of MMA may have clinical impact. Key words: Middle meningeal artery (MMA), aneurysm of the middle meningeal artery, epidural he- matoma, anatomical variation of MMA. TOPOGRAPHY OF THE MIDDLE MENINGEAL ARTERY AND ITS BRANCHES Middle meningeal artery (MMA) [1] is most commonly the strongest branch of maxillary artery (from external carotid artery) [2]. It supplies blood to cranial dura mater, and through the numerous perforating branches it nourishes also periosteum of the inner aspect of cranial bones. It enters the middle cranial fossa through the foramen spinosum, and courses between the dura mater and the inner aspect of the vault of the skull. Next it divides into two terminal branches — frontal (anterior) which supplies blood to bones forming anterior cranial fossa and the anterior part of the middle cranial fossa; parietal branch (posterior), which runs more horizontally toward the back and supplies posterior part of the middle cranial fossa and supratentorial part of the posterior cranial fossa. -

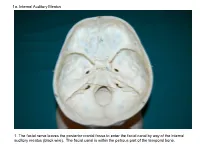

1A. Internal Auditory Meatus

1a. Internal Auditory Meatus 1. The facial nerve leaves the posterior cranial fossa to enter the facial canal by way of the internal auditory meatus (black wire). The facial canal is within the petrous part of the temporal bone. 1b. Internal Auditory Meatus The facial nerve leaves the posterior cranial fossa to enter the facial canal by way of the internal auditory meatus (black wire). 2. Hiatus of the Canal and Groove for the Greater Superficial Petrosal Nerve The greater superficial petrosal nerve leaves the facial canal to enter the middle cranial fossa by way of the hiatus of the canal for the greater superficial petrosal nerve (black wire). 3. Pterygoid Canal at Anterior Lip of the Lacerate Foramen The greater superficial petrosal nerve is joined by the deep petrosal nerve to form the nerve of the pterygoid canal (black and red wire). This nerve leaves the middle cranial fossa to enter the pterygopalatine fossa by way of the pterygoid canal. The posterior opening of the pterygoid canal is at the anterior lip of the lacerate foramen. The greater superficial nerve and the deep petrosal nerve travel within the cavernous sinus. 4. Pterygopalatine Fossa Seen Through the Pterygomaxillary Fissure The anterior opening of the pterygoid canal is into the pterygopalatine fossa (black wire). The pterygopalatine fossa is located medial to the pterygomaxillary fissure and contains the pterygopalatine ganglion. 5. External Auditory Meatus The chorda tympani nerve leaves the facial canal and crosses the middle ear (black wire). It then leaves the middle ear to arrive in the infratemporal fossa by way of the petrotympanic fissure.