Idealism and Abstract Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures by Sean Delaine Griffin 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle by Sean Delaine Griffin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Gail Lenhoff, Chair The monastic chroniclers of medieval Rus’ lived in a liturgical world. Morning, evening and night they prayed the “divine services” of the Byzantine Church, and this study is the first to examine how these rituals shaped the way they wrote and compiled the Povest’ vremennykh let (Primary Chronicle, ca. 12th century), the earliest surviving East Slavic historical record. My principal argument is that several foundational accounts of East Slavic history—including the tales of the baptism of Princess Ol’ga and her burial, Prince Vladimir’s conversion, the mass baptism of Rus’, and the martyrdom of Princes Boris and Gleb—have their source in the feasts of the liturgical year. The liturgy of the Eastern Church proclaimed a distinctively Byzantine myth of Christian origins: a sacred narrative about the conversion of the Roman Empire, the glorification of the emperor Constantine and empress Helen, and the victory of Christianity over paganism. In the decades following the conversion of Rus’, the chroniclers in Kiev learned these narratives from the church services and patterned their own tales of Christianization after them. The ii result was a myth of Christian origins for Rus’—a myth promulgated even today by the Russian Orthodox Church—that reproduced the myth of Christian origins for the Eastern Roman Empire articulated in the Byzantine rite. -

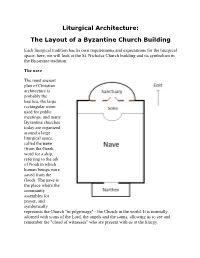

Liturgical Architecture: the Layout of a Byzantine Church Building

Liturgical Architecture: The Layout of a Byzantine Church Building Each liturgical tradition has its own requirements and expectations for the liturgical space; here, we will look at the St. Nicholas Church building and its symbolism in the Byzantine tradition. The nave The most ancient plan of Christian architecture is probably the basilica, the large rectangular room used for public meetings, and many Byzantine churches today are organized around a large liturgical space, called the nave (from the Greek word for a ship, referring to the ark of Noah in which human beings were saved from the flood). The nave is the place where the community assembles for prayer, and symbolically represents the Church "in pilgrimage" - the Church in the world. It is normally adorned with icons of the Lord, the angels and the saints, allowing us to see and remember the "cloud of witnesses" who are present with us at the liturgy. At St. Nicholas, the nave opens upward to a dome with stained glass of the Eucharist chalice and the Holy Spirit above the congregation. The nave is also provided with lights that at specific times the church interior can be brightly lit, especially at moments of great joy in the services, or dimly lit, like during parts of the Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts. The nave, where the congregation resides during the Divine Liturgy, at St. Nicholas is round, representing the endlessness of eternity. The principal church building of the Byzantine Rite, the Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, employed a round plan for the nave, and this has been imitated in many Byzantine church buildings. -

& What You Can Do to Help… Why It Has Endured 2000 Years …

Seeking and Understanding your Religious Heritage Why it has endured 2000 years …. & What you can do to help… WEAVING THE FABRIC OF HISTORY Το έργο αυτό έρχεται να συμπληρώσει και να αναδείξει την πίστη των χριστιανών μιας ιστορικής και πολιτιστικής κληρονομίας 2000 και πλέων ετών . Για αυτό και πρέπει να διατηρηθεί και να αντέξει στους αιώνες των αιώνων . Οι κτήτορες αυτού του Ιερού Ναού θα μείνουν στην ιστορία και θα τους μνημονεύουν αιωνίως . Θα καμαρώνουν τα εγγόνια τους , οι συγγενείς τους και οι επόμενες γενιές για την συμβολή τους σε αυτό το Έργο . Που είναι καταφύγιο και αποκούμπι για τις κακουχίες και τις θεομηνίες των καιρών μας. Θα μείνουμε στην μνήμη των συγγενών μας ως πρωτοπόροι και θεμελιωτές μια αντάξιας προσπάθειας συνεχίσεως της ιστορικής βυζαντινής κληρονομιάς των προγόνων μας. Τέλος όλοι μπορούν και πρέπει να συμβάλουν στην ανέγερση του Ιερού Ναού για την συνέχιση της Ιστορίας και τις Ορθοδοξίας. This Authentic Basilica complements and highlights Christian beliefs that have a historical, cultural and religious heritage of 2000 years and more. We have been given the responsibility to continue this legacy and help it to endure for centuries to come. The faithful that have and will continue to contribute to help build this holy temple will be remembered in history. The benefactors of this historic project will bestow upon their children and grandchildren for many generations the opportunity to become the torch bearers of Christendom. HOLY RELICS SOLEA Sanctuary NAVE Dedication or Sponsoring opportunities for Bell Tower Bell Tower- three- tiered Bell Tower $100,000.00 (Donors will have individual recognition both upstairs and downstairs on interior walls of Bell Tower) Bell Tower Elevator Handicap Accessible $150,000.00 (Donor will have individual recognition outside elevator as well as inside elevator) Bell Large $ 14,000.00 Bell Medium $ 9,000.00 Bell Small $ 6,000.00 (Donors will have their names engraved on bells.) The three bells will be made in Romania. -

Hymns and Readings for Sunday, February 17, 2019 Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee - Triodion Begins

WELCOME TO SAINT CATHERINE GREEK ORTHODOX CHURCH “There are no strangers here; only friends you have not met!” 5555 S. Yosemite Street, Greenwood Village, CO 80111 Phone 303-773-3411 ● Fax 303-773-6641 www.stcatherinechurch.org ● [email protected] Office hours: 9am - 4pm Sundays hours of service: Orthros 8:15am Divine Liturgy 9:30am Weekdays hours of service: Orthros 8:15am, Divine Liturgy 9am Clergy: Father Louis J. Christopulos, Protopresbyter ● Father Paul Fedec, Archpriest ● Deacon John Kavas Staff: Michelle Smith, Office Administrator ● Alina Buzdugan, Ministry Coordinator/Communications/Chanting Alex Demos, Pastoral Assistant to Fr. Lou and Youth Director Brenda Lucero, Accountant ● Steven Woodruff, Facility Manager 2019 Parish Council: Stu Weinroth, President ● Jenée Horan, 1st VP Fellowship ● Dr. Leon Greos, 2nd VP Stewardship Helen Terry, Secretary ● Brian Farr, Treasurer ● Spiros Deligiannis ● Billy Halax ● Dr. Jeff Holen ● Eldon Keller Louis Sokach ● Andy Stathopulos ● George Strompolos ● Dr. Harry Stathos ● Mark Terry HYMNS AND READINGS FOR SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 2019 SUNDAY OF THE PUBLICAN AND THE PHARISEE - TRIODION BEGINS Resurrectional Apolytikion – 5h Tone (Green Hymnal pg. 85) Eternal with the Father and the Spirit is the Word, Who of a Virgin was begotten for our salvation. As the faithful we both praise and worship Him, for in the flesh did He consent to ascend unto the Cross, and death did He endure and He raised unto life the dead through His all glorious resurrection. Hymn of St. Catherine - 5th Tone We sing praises in memory of the bride of Christ, Catherine the Holy Protectress of Holy Mount Sinai, of her who is our help- er and our comforter, silencing the impious ones with her brilliance. -

The Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom an English Translation from the Greek, with Commentary, of the Divine Liturgy of St

The Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom An English translation from the Greek, with commentary, of the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom The annotations in this edition are extracted from two books by Fr. Alexander Schmemann, of blessed memory: 1) The Eucharist published in 1987, and, 2) For The Life of The World, 1963, 1973, both published by Saint Vladimir’s Seminary Press. Fr. Schmemann died in 1983 at the age of 62 having been Dean of St. Vladimir’s Seminary for the 20 years previously. Any illumination for the reader of the meaning of the Liturgy is directly from Fr. Schmemann’s work; any errors are directly the fault of the extractor. In this edition the quiet prayers of the priest are indicated by being in blue italics, Scripture references are in red, the Liturgical text is in blue, and the commentary is in black. (Traditionally, the service of Orthros is celebrated right before each Liturgy. The traditional end of the Orthros is the Great Doxology. In our church, the end of the Orthros is separated from the Great Doxology by the Studies in the Faith and the Memorials. Thus, it appears that the Great Doxology is the start of The Eucharist, but that is not the case. [ed.]) The Liturgy of the Eucharist is best understood as a journey or procession. It is a journey of the Church into the dimension of the kingdom, the manner of our entrance into the risen life of Christ. It is not an escape from the world, but rather an arrival at a vantage point from which we can see more deeply into the reality of the world. -

Christianity Islam

Christianity/Islam/Comparative Religion Frithjof Schuon Th is new edition of Frithjof Schuon’s classic work contains: Christianity a fully revised translation from the original French; an appendix of selections from letters and other previously unpublished writings; comprehensive editor’s notes and preface by James Cutsinger; Islam an index and glossary of terms. Perspectives on Esoteric Ecumenism “Schuon’s thought does not demand that we agree or disagree, A New Translation with Selected Letters but that we understand or do not understand. Such writing is of rare and lasting value.” —Times Literary Supplement C “I have met with no more impressive work in the comparative study of Oriental and hristianity Occidental religion.” —T. S. Eliot, Nobel laureate for literature, on Schuon’s fi rst book, Th e Transcendent Unity of Religions “[Schuon is] the most important religious thinker of our century.” —Huston Smith, author of Th e World’s Religions and Th e Soul of Christianity “In reading Schuon I have the impression that I am going along parallel to him, and once in a while I will get a glimpse of what he means in terms of my own tradition and experience.… I think that he has exactly the right view.… I appreciate him more and more.… I am grateful for the chance to be in contact with people like him.” —Th omas Merton (from a letter to Marco Pallis) / “[Schuon is] the leading philosopher of Islamic theosophical mysticism.” —Annemarie Schimmel, Harvard University I slam “[Th is] collection has some essays that will interest students engaged in the comparative study of … Islam and Christianity. -

The Divine Liturgy John Chrysostom

The Divine Liturgy of our Father among the Saints John Chrysostom (With Commentary and Notes) The Divine Liturgy 2 The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom is today the primary worship service of over 300 million Orthodox Christians around the world, from Greece to Finland, from Russia to Tanzania, from Japan to Kenya, Bulgaria to Australia. It is celebrated in dozens of languages, from the original Greek it was written in to English and French, Slavonic and Swahili, Korean and Arabic. What does the word Liturgy mean? Liturgy is a Greek word that in classical times referred to the performance of a public duty; in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament made some 300 years before the coming of Christ and still used by the Church today, it referred to worship in the Temple in Jerusalem; and for Orthodox Christians it has come to mean the public worship of the Church. Because Liturgy is always a corporate, communal action, it is often translated as ―the work of the people‖ and because it is prefaced by the word ―Divine‖ it is specifically the work of God‘s people and an experience of God‘s coming Kingdom here and now by those who gather to worship Him. This means that the Liturgy is not something that the clergy "performs" for the laity. The Liturgy was never meant to be a performance or a spectacle merely to be witnessed by onlookers. All who are present for worship must be willing, conscious and active participants and not merely passive spectators. The laity con-celebrate with the officiating clergy as baptized believers and members of the "royal priesthood…a people belonging to God" (1 Peter 2:9). -

The Seventh Ecumenical Council and the Veneration of Icons in Orthodoxy

Acta Theologica 2014 34(2): 77-93 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v34i2.5 ISSN 1015-8758 © UV/UFS <http://www.ufs.ac.za/ActaTheologica> A. Nicolaides THE SEVENTH ECUMENICAL COUNCIL AND THE VENERATION OF ICONS IN ORTHODOXY ABSTRACT In the Orthodox Christian tradition, icons are not regarded as works of art; they are rather a visual gospel and windows into the spiritual realm. They are intended to assist believers to be more contemplative and prayerful. They guide believers into a life of prayer. There are, however, those who consider them to be idolatrous. Such a belief is erroneous, since the honouring of created beings does not detract from being totally devoted to the Creator in whose image they were created. Icons portraying God’s grace are sanctifying and help affirm the faith of Orthodox believers. Icons are a concrete theology that instructs and leads believers to a spiritual reality and ultimately sanctify them as they transform them. They ultimately serve as conduits to the healing of body and soul through the grace of God and are essentially a prelude to the final transfiguration of the world. 1. INTRODUCTION The Eastern Orthodox Church or Orthodox Church is well known for its use of icons. It is a “right-believing” Church, from the Greek “ὀρθόδοξος”, which literally means “straight path”. It is total faithfulness and dedication to the truth. The founder of the Church is Jesus Christ who is the Divine Word and personal revelation of God the Father. In its churches and in the homes of its adherents, one encounters many Holy icons. -

Archangel Michael Church Η Εκκλησία Του Αρχαγγέλου Μιχαήλ 100 Fairway Drive, Port Washington, NY 11050 (516) 944-3180 ~ Clergy: Fr

Archangel Michael Church Η Εκκλησία του Αρχαγγέλου Μιχαήλ 100 Fairway Drive, Port Washington, NY 11050 (516) 944-3180 ~ www.archangelmichaelchurch.org Clergy: Fr. John Lardas, Fr. Michael Palamara, Fr. Dennis Strouzas Ἦχος αʹ /First Tone ~ Ἑωθινὸν Ζʹ /7th Morning Gospel October 11th, 2020 ~ 4th Sunday of Luke The Holy Apostle and Deacon Philip On October 11th, today, we celebrate the memory of St Philip one of the 70 Apostles, and one of the 7 deacons who were chosen on the same day as St Stephen the first martyr. It is known from Acts that he had 4 daughters with the gift of prophecy and he preached throughout Samaria. He also has a very interesting encounter with a eunuch servant from Ethiopia. We read in the encounter that the eunuch was interested in the Jewish faith and happened to be reading the scroll of the book of Isaiah. This book is beautiful but he said he could not understand the Scriptures without a guide, which St Philip became for him. After his guidance, the Ethiopian was baptized and became one of the first Afri- can Christians. On another note, here at the Archangel Michael Church St Philip the Deacon is very special to us because he is on our iconostasis. He is on the door on the right of the altar next to St John the Baptist. As a dea- con he was known for his service as a clergyman of the early Church so it is appropriate to have him on next to the Altar. Άγιος Φίλιππος ο Απόστολος ένας από τους επτά Διακόνους Ο Άγιος Φίλιππος καταγόταν από την Καισαρεία της Παλαιστίνης και ήταν διάκονος μεταξύ των επτά διακόνων της πρώτης Εκκλησίας στην Ιερουσαλήμ (Πράξ. -

The Icon of the Pochayiv Mother of God: a Sacred Relic Between East and West

The Icon of the Pochayiv Mother of God: A Sacred Relic between East and West Franklin Sciacca Hamilton College Clinton, New York Introduction There are myriad icons of the Mother of God that are designated as “miracle-working” (chudotvornyi in Ukrainian and Russian) in the Orthodox and Catholic lands of Eastern Europe. Thaumaturgic powers are often ascribed to the icon itself and therefore such panels are venerated with particular devotion. Pilgrims seek physical contact with these objects. From the lands of medieval Kievan Rus’, there are four surviving icons with Byzantine pedigree that achieved “miracle- working” status as early as the 11th c.: The Vladimir icon (known in Ukrainian tradition as Vyshhorod, after the location of the convent north of Kiev where it was originally kept); the Kievo-Pechersk icon of the Dormition; the Kholm icon (attributed to Evangelist Luke); and the so-called Black Madonna of Częstochowa (originally housed in Belz, and for the last 600 years in the Jasna Gora monastery in Poland). All of them are surrounded by complex folkloric legends of origin and accounts of miraculous interventions. In later centuries, numerous other wonder-working icons appeared in Ukrainian, Belarusian, Russian, Polish, Balkan lands, Figure 1: Pochayiv Mother Of among which is a relative late-comer (known from the late 16th c.)--The icon God in Dormition Cathedral, of the Mother and Child that was venerated at the Pochayiv monastery in Western Pochayiv Lavra. Ukraine. This small, originally domestic, icon achieved significant cult status throughout Eastern Europe, both in Orthodox and Catholic milieus. This article seeks to examine the origin of the icon in the context of the development of the monastery whose reputation was built as its repository. -

Annunciation of the Theotokos 3-25-18.Pub

ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗ ΟΡΘΟΔΟΞΗ ΚΟΙΝΟΤΗΤΑ ΤΩΝ ΤΑΞΙΑΡΧΩΝ TAXIARCHAE/ARCHANGELS GREEK ORTHODOX CHURCH 25 Bigelow Avenue, Watertown, MA 02472 617.924.8182 Phone # Fax: 617.924.4124 Website: www.goarchangels.org Office: [email protected] Rev. Fr. Athanasios Nenes, Parish Priest Cell Phone: 914.479.8096 Email: [email protected] Rev. Fr. Nicholas Mueller, Parish Ministries Assistant Cell Phone: 916.517.2298 Email: [email protected] The Sunday Weekly Bulletin is posted on our website at www.goarchangels.org. Annunciation of the Theotokos March 25, 2018 ORTHROS 8:30AM - DIVINE LITURGY 9:30AM Paraklesis - Every Thursday to the Panagia Gorgoipikoos 6PM. Pre-Sanctified Liturgy– Wed. 3/28 at 6PM St. Nicholas, Lexington Saturday of Lazarus - March 31st Orthos 8:45 Liturgy 9:45 AM Communion breakfast, and the weaving of palm crosses. HYMNS OF THE DAY Resurrectional Apolytikion in the First Mode: Savior, Your tomb was sealed with a stone. Soldiers kept watch over Your sacred body. Yet, You rose on the third day giving life to the world. Wherefore the powers of heaven cried out, "O Giver of Life, glory to Your Resurrection O Christ; glory to Your Kingdom, glory to Your dispensation who alone are the Loving One." Τοῦ λίθου σφραγισθέντος ὑπὸ τῶν Ἰουδαίων, καὶ στρατιωτῶν φυλασσόντων τὸ ἄχραντόν σου σῶμα, ἀνέστης τριήμερος Σωτήρ, δωρούμενος τῷ κόσμῳ τὴν ζωήν. Διὰ τοῦτο αἱ Δυνάμεις τῶν οὐρανῶν ἐβόων σοι Ζωοδότα· Δόξα τῇ ἀναστάσει σου Χριστέ, δόξα τῇ Βασιλείᾳ σου, δόξα τῇ οἰκονομίᾳ σου, μόνε Φιλάνθρωπε. Apolytikion for Sun. of St. Mary of Egypt in the Plagal Fourth Mode: The image of God, was faithfully preserved in you, O Mother. -

(Greek for Supplication). It Depicts Christ in the Centre with the Mother of God and John the Baptist on Either Side

When therefore you see the priest delivering [the supper] unto you, account not that it is the priest that does so, but that it is Christ's hand that is stretched out ... Believe, therefore, that even now it is that supper at which he himself sat down. For this is in no respect different from that.420 607 The main icon of the third row is the Deisis icon (Greek for supplication). It depicts Christ in the centre with the Mother of God and John the Baptist on either side. Sometimes the Archangels Michael and Gabriel are also included. To the right and left of the Deisis icon are icons of the apostles. The whole Deisis composition represents the Church in prayer before Christ: the heavenly Church and the Church on earth are united in a single intercession before the throne of the Lord. This signifies the calling of the Church to incessantly keep vigil and offer prayers for the whole world. 608 In the fourth row of the iconostasis are icons of the Old Testament prophets who in their writings announced the coming of the Messiah. This row indicates the unity of the two Testaments in the Revelation of the Word of God. Images of the prophets may also be seen in the upper levels of the nave or sanctuary. In the centre of this row of prophets is the icon of Our Lady of the Sign. On her breast is a round medallion depicting the Christ-Child, Emmanuel. This icon represents the fulfilment of the Old Testament expectation of the coming of Christ the Saviour: "Behold, a virgin shall conceive" (Is 7:14, кsv-CE).