Christianity Islam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(“At Variance with Guénon”) of "Frithjof Schuon: Messenger of The

from: Frithjof Schuon: Messenger of the Perennial Philosophy ISBN: 978-1-935493-08-2 from the free Online Library at http://www.frithjofschuon.com/ 11. At Variance with Guénon In my early youth, my salvation was Shrī Shankara, and with him, spiritual virtue; And so I was able to learn: only inspiration, And not vain thinking, can give Wisdom. Then came the notion of tradition: Only the sacred may carry the sacred. All this Guénon wrote in his works with great diligence And zeal. But much still remained to be said!1 Frithjof Schuon always respected the metaphysical and conceptual frame- work articulated by René Guénon, whose writings were particularly important to him at the time when he was beginning to formulate his own perspective. Starting in 1939 and continuing throughout the rest of his life, Schuon delved into many subjects that Guénon never considered or only touched upon lightly, including Buddhism and American Indian spiritu- ality, sacred art in its diverse forms, and, especially, the operative aspects of spiritual realization—prayer of the heart and the human virtues. Martin Lings, who was Guénon’s personal assistant in Cairo during the 1940s, later expressed an observation that first became apparent in these years: “There is nothing in Guénon that is not to be found in Schuon. There is much in Schuon that is not to be found in Guénon.”2 When, after the war, com- munication could be resumed between Guénon in Cairo and Schuon in Lausanne, Guénon was generally supportive of Schuon’s point of view on these subjects and particularly appreciative of Schuon’s interest in American Indian spirituality. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures by Sean Delaine Griffin 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle by Sean Delaine Griffin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Gail Lenhoff, Chair The monastic chroniclers of medieval Rus’ lived in a liturgical world. Morning, evening and night they prayed the “divine services” of the Byzantine Church, and this study is the first to examine how these rituals shaped the way they wrote and compiled the Povest’ vremennykh let (Primary Chronicle, ca. 12th century), the earliest surviving East Slavic historical record. My principal argument is that several foundational accounts of East Slavic history—including the tales of the baptism of Princess Ol’ga and her burial, Prince Vladimir’s conversion, the mass baptism of Rus’, and the martyrdom of Princes Boris and Gleb—have their source in the feasts of the liturgical year. The liturgy of the Eastern Church proclaimed a distinctively Byzantine myth of Christian origins: a sacred narrative about the conversion of the Roman Empire, the glorification of the emperor Constantine and empress Helen, and the victory of Christianity over paganism. In the decades following the conversion of Rus’, the chroniclers in Kiev learned these narratives from the church services and patterned their own tales of Christianization after them. The ii result was a myth of Christian origins for Rus’—a myth promulgated even today by the Russian Orthodox Church—that reproduced the myth of Christian origins for the Eastern Roman Empire articulated in the Byzantine rite. -

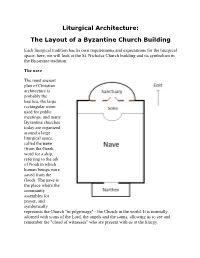

Liturgical Architecture: the Layout of a Byzantine Church Building

Liturgical Architecture: The Layout of a Byzantine Church Building Each liturgical tradition has its own requirements and expectations for the liturgical space; here, we will look at the St. Nicholas Church building and its symbolism in the Byzantine tradition. The nave The most ancient plan of Christian architecture is probably the basilica, the large rectangular room used for public meetings, and many Byzantine churches today are organized around a large liturgical space, called the nave (from the Greek word for a ship, referring to the ark of Noah in which human beings were saved from the flood). The nave is the place where the community assembles for prayer, and symbolically represents the Church "in pilgrimage" - the Church in the world. It is normally adorned with icons of the Lord, the angels and the saints, allowing us to see and remember the "cloud of witnesses" who are present with us at the liturgy. At St. Nicholas, the nave opens upward to a dome with stained glass of the Eucharist chalice and the Holy Spirit above the congregation. The nave is also provided with lights that at specific times the church interior can be brightly lit, especially at moments of great joy in the services, or dimly lit, like during parts of the Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts. The nave, where the congregation resides during the Divine Liturgy, at St. Nicholas is round, representing the endlessness of eternity. The principal church building of the Byzantine Rite, the Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, employed a round plan for the nave, and this has been imitated in many Byzantine church buildings. -

Origen of Alexandria and St. Maximus the Confessor: an Analysis and Critical Evaluation of Their Eschatological Doctrines

Origen of Alexandria and St. Maximus the Confessor: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of Their Eschatological Doctrines by Edward Moore ISBN: 1-58112-261-6 DISSERTATION.COM Boca Raton, Florida USA • 2005 Origen of Alexandria and St. Maximus the Confessor: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of Their Eschatological Doctrines Copyright © 2004 Edward Moore All rights reserved. Dissertation.com Boca Raton, Florida USA • 2005 ISBN: 1-58112-261-6 Origen of Alexandria and St. Maximus the Confessor: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of Their Eschatological Doctrines By Edward Moore, S.T.L., Ph.D. Table of Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................VI ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................VII PREFACE.....................................................................................................................VIII INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 ORIGEN, MAXIMUS, AND THE IMPORTANCE OF ESCHATOLOGY ....................................... 1 THE HISTORY AND IMPORTANCE OF ESCHATOLOGY IN CHRISTIAN THOUGHT – SOME BRIEF REMARKS. ............................................................................................................. 3 CHAPTER 1: ORIGEN’S INTELLECTUAL BACKGROUND................................... 15 BRIEF BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH...................................................................................... -

& What You Can Do to Help… Why It Has Endured 2000 Years …

Seeking and Understanding your Religious Heritage Why it has endured 2000 years …. & What you can do to help… WEAVING THE FABRIC OF HISTORY Το έργο αυτό έρχεται να συμπληρώσει και να αναδείξει την πίστη των χριστιανών μιας ιστορικής και πολιτιστικής κληρονομίας 2000 και πλέων ετών . Για αυτό και πρέπει να διατηρηθεί και να αντέξει στους αιώνες των αιώνων . Οι κτήτορες αυτού του Ιερού Ναού θα μείνουν στην ιστορία και θα τους μνημονεύουν αιωνίως . Θα καμαρώνουν τα εγγόνια τους , οι συγγενείς τους και οι επόμενες γενιές για την συμβολή τους σε αυτό το Έργο . Που είναι καταφύγιο και αποκούμπι για τις κακουχίες και τις θεομηνίες των καιρών μας. Θα μείνουμε στην μνήμη των συγγενών μας ως πρωτοπόροι και θεμελιωτές μια αντάξιας προσπάθειας συνεχίσεως της ιστορικής βυζαντινής κληρονομιάς των προγόνων μας. Τέλος όλοι μπορούν και πρέπει να συμβάλουν στην ανέγερση του Ιερού Ναού για την συνέχιση της Ιστορίας και τις Ορθοδοξίας. This Authentic Basilica complements and highlights Christian beliefs that have a historical, cultural and religious heritage of 2000 years and more. We have been given the responsibility to continue this legacy and help it to endure for centuries to come. The faithful that have and will continue to contribute to help build this holy temple will be remembered in history. The benefactors of this historic project will bestow upon their children and grandchildren for many generations the opportunity to become the torch bearers of Christendom. HOLY RELICS SOLEA Sanctuary NAVE Dedication or Sponsoring opportunities for Bell Tower Bell Tower- three- tiered Bell Tower $100,000.00 (Donors will have individual recognition both upstairs and downstairs on interior walls of Bell Tower) Bell Tower Elevator Handicap Accessible $150,000.00 (Donor will have individual recognition outside elevator as well as inside elevator) Bell Large $ 14,000.00 Bell Medium $ 9,000.00 Bell Small $ 6,000.00 (Donors will have their names engraved on bells.) The three bells will be made in Romania. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

The Milk of the Virgin: the Prophet, the Saint and the Sage by Renaud Fabbri

From the World Wisdom online library: www. worldwisdom.com/public/library/default.aspx The following essay is found in Sacred Web 20, edited by M. Ali Lakhani The Milk of the Virgin: The Prophet, the Saint and the Sage by Renaud Fabbri Prophets, saints, and sages: The prophet brings a form of faith — a religion; The saint lives it; the sage opens A luminous realm of Pure Spirit Beyond form. Prophets are also wise men, Yet about the highest Truth they speak softly; To the sage, holiness bestows light. God and our heart are united in eternity. (Frithjof Schuon)1 There have been a few controversies in the last decade about the teaching and personality of the 20th century Perennialist author and founder of the Maryamiyyah Sufi order, Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998), 1 Frithjof Schuon, Songs without Names XII / XVI (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2007). also known under the name of Sheikh Isa Nur Ad-Din Ahmad. These controversies have been reflected to various degrees in articles published by traditionalist journals as well as in recent scholarly publications. In the following paper, it will be argued that Frithjof Schuon is best understood neither as the founder of a new religion (a prophet in the classical sense of the word) nor as a Muslim saint, but as a universal sage, a spokesman for the religio perennis whose connection with Islam, although providential, remains secondary in the context of his message of esoterism, universality and primordiality. Before we engage in an attempt at defining a sage, we will need to refute two types of criticisms against Schuon. -

EARL 8/2 No. 2

ATTRIDGE/VALENTINIAN AND SETHIAN APOCALYPSES 173 Valentinian and Sethian Apocalyptic Traditions* HAROLD W. ATTRIDGE The paper reexamines the relationship between “apocalyptic” and “gnostic” traditions, on the assumption that global definitions of these phenomena are problematic. Valentinian and Sethian corpora in the Nag Hammadi collection display different appropriations of apocalyptic literary forms and conceptual schemes. Apart from a few late works with traces of Valentinian positions, this tradition largely ignores features characteristic of apocalyptic literature. Valentinian eschatology seems to be founded primarily on philosophical cosmology and psychology. Sethian texts preserve many features of Jewish revelatory literature, and many details associated with various eschatological schemes familiar from apocalyptic sources. The most extensive use of the characteristic “heavenly ascent” topos in Sethian literature, however, seems to be a third-century development, perhaps responding to contemporary forms of religious propaganda. It has been almost forty years since R. M. Grant made his famous, and frequently discussed, suggestion that Gnosticism was born out of disap- pointed apocalyptic hopes.1 While containing an element of truth, the very formulation seems curiously dated. At the end of the millennium we are much more aware of the difficulties of dealing with each term of *A version of this paper was presented to the joint session of the Nag Hammadi and Pseudepigrapha groups at the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature in Orlando, November 22, 1998. The subject of the joint session was the relationship of “apocalyptic” and “Gnosticism.” 1. Robert M. Grant, Gnosticism and Early Christianity (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959; rev. ed. 1966), 27–38. -

Hymns and Readings for Sunday, February 17, 2019 Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee - Triodion Begins

WELCOME TO SAINT CATHERINE GREEK ORTHODOX CHURCH “There are no strangers here; only friends you have not met!” 5555 S. Yosemite Street, Greenwood Village, CO 80111 Phone 303-773-3411 ● Fax 303-773-6641 www.stcatherinechurch.org ● [email protected] Office hours: 9am - 4pm Sundays hours of service: Orthros 8:15am Divine Liturgy 9:30am Weekdays hours of service: Orthros 8:15am, Divine Liturgy 9am Clergy: Father Louis J. Christopulos, Protopresbyter ● Father Paul Fedec, Archpriest ● Deacon John Kavas Staff: Michelle Smith, Office Administrator ● Alina Buzdugan, Ministry Coordinator/Communications/Chanting Alex Demos, Pastoral Assistant to Fr. Lou and Youth Director Brenda Lucero, Accountant ● Steven Woodruff, Facility Manager 2019 Parish Council: Stu Weinroth, President ● Jenée Horan, 1st VP Fellowship ● Dr. Leon Greos, 2nd VP Stewardship Helen Terry, Secretary ● Brian Farr, Treasurer ● Spiros Deligiannis ● Billy Halax ● Dr. Jeff Holen ● Eldon Keller Louis Sokach ● Andy Stathopulos ● George Strompolos ● Dr. Harry Stathos ● Mark Terry HYMNS AND READINGS FOR SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 2019 SUNDAY OF THE PUBLICAN AND THE PHARISEE - TRIODION BEGINS Resurrectional Apolytikion – 5h Tone (Green Hymnal pg. 85) Eternal with the Father and the Spirit is the Word, Who of a Virgin was begotten for our salvation. As the faithful we both praise and worship Him, for in the flesh did He consent to ascend unto the Cross, and death did He endure and He raised unto life the dead through His all glorious resurrection. Hymn of St. Catherine - 5th Tone We sing praises in memory of the bride of Christ, Catherine the Holy Protectress of Holy Mount Sinai, of her who is our help- er and our comforter, silencing the impious ones with her brilliance. -

From Logos to Bios: Hellenic Philosophy and Evolutionary Biology

From Logos to Bios: Hellenic Philosophy and Evolutionary Biology by Wynand Albertus de Beer submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of D Litt et Phil in the subject Religious Studies at the University of South Africa Supervisor: Prof Danie Goosen February 2015 Dedicated with grateful acknowledgements to my supervisor, Professor Danie Goosen, for his wise and patient guidance and encouragement throughout my doctoral research, and to the examiners of my thesis for their helpful comments and suggestions. From Logos to Bios: Hellenic Philosophy and Evolutionary Biology by W.A. de Beer Degree: D Litt et Phil Subject: Religious Studies Supervisor: Prof Danie Goosen Summary: This thesis deals with the relation of Hellenic philosophy to evolutionary biology. The first part entails an explication of Hellenic cosmology and metaphysics in its traditional understanding, as the Western component of classical Indo-European philosophy. It includes an overview of the relevant contributions by the Presocratics, Plato, Aristotle, and the Neoplatonists, focussing on the structure and origin of both the intelligible and sensible worlds. Salient aspects thereof are the movement from the transcendent Principle into the realm of Manifestation by means of the interaction between Essence and Substance; the role of the Logos, being the equivalent of Plato’s Demiurge and Aristotle’s Prime Mover, in the cosmogonic process; the interaction between Intellect and Necessity in the formation of the cosmos; the various kinds of causality contributing to the establishment of physical reality; and the priority of being over becoming, which in the case of living organisms entails the primacy of soul over body. -

The Substance of Fritjohf Schuon's Thinking About the Point of Religions

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 6, Ver. 6 (June. 2017) PP 87-92 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Substance of Fritjohf Schuon’s Thinking about the Point of Religions Zulkarnaen Ph.D Student at State Islamic University of North Sumatra (UINSU), Medan, Indonesia Lecturer at State Islamic University of North Sumatra (UINSU), Medan, Indonesia Abstract:religion is not limited by what isincluded but by what is excluded by it, this lack of coverage will not destroy the deepest religious content. The substance of a human being is to believe in the existence of Lord. This is acknowledged in tauhid rububiyah of Islām people, while what distinguishes Islām from other religions is tauhiduluhiyyah. Basically, the human having religion is same. The concept of Lord in Islâm is based on revelation. The revelation here is not imagination at all as the fancy of a great poet or the artist's claim to themselves. The revelation here is not the apostolic’s inspiration as claimed by biblical writers of the Bible, not the illuminative intuition of a scientist or a sharp-looking expert. The substance of FrithjofSchuont thought about the point of religions, although the external level of religion is different, but in essence all religions are the same. In other words, the unity of religions occurs at a transcendent level. Schuon'sargues that all religions have two realities or essence, namely exoteric and esoteric. The nature of exoterics is the essence of birth, which all religions have different, contradictory, contradictory dogmas, laws, rituals and beliefs. -

The Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom an English Translation from the Greek, with Commentary, of the Divine Liturgy of St

The Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom An English translation from the Greek, with commentary, of the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom The annotations in this edition are extracted from two books by Fr. Alexander Schmemann, of blessed memory: 1) The Eucharist published in 1987, and, 2) For The Life of The World, 1963, 1973, both published by Saint Vladimir’s Seminary Press. Fr. Schmemann died in 1983 at the age of 62 having been Dean of St. Vladimir’s Seminary for the 20 years previously. Any illumination for the reader of the meaning of the Liturgy is directly from Fr. Schmemann’s work; any errors are directly the fault of the extractor. In this edition the quiet prayers of the priest are indicated by being in blue italics, Scripture references are in red, the Liturgical text is in blue, and the commentary is in black. (Traditionally, the service of Orthros is celebrated right before each Liturgy. The traditional end of the Orthros is the Great Doxology. In our church, the end of the Orthros is separated from the Great Doxology by the Studies in the Faith and the Memorials. Thus, it appears that the Great Doxology is the start of The Eucharist, but that is not the case. [ed.]) The Liturgy of the Eucharist is best understood as a journey or procession. It is a journey of the Church into the dimension of the kingdom, the manner of our entrance into the risen life of Christ. It is not an escape from the world, but rather an arrival at a vantage point from which we can see more deeply into the reality of the world.