The Milk of the Virgin: the Prophet, the Saint and the Sage by Renaud Fabbri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the Editor ne should thank Gustavo Polit for going to such length to point out O various confusions, oversights, errors, incomprehensions, and biases which he finds in our note responding to his and Patrick Moore’s letters.1 While some of Polit’s remarks arise from misunderstanding, and with many of them one can agree (so comprehensive is their scope), he does identify genuine disagreement between us. As for misunderstanding: One does not overlook the origin of modernity within Christendom, though this was not because of a lack of genuine gnosis within the Church, as again, Jean Borella has amply documented (Guenonian Esoterism and Christian Mystery). The point was simply that Christianity has in fact borne the brunt of the modernist attack: and in fact, has the persistence of jnana prevented the ongoing modernization of India? Again, one does not reduce the universal metaphysical Order to the formal orders as Polit fears: this would amount to eliding the Uncreated order and the formless spiritual order of Creation! And then, it is no intention of ours to diminish the scope and authority of spiritual intellect merely by referring it to the metaphysical orientation of spiritual life as evoked by Mr. Lakhani’s editorial in Volume 30 of Sacred Web. As for agreement: when Polit says that metaphysical doctrine can vary only in ‘formulation’, while its Truth stands invariant over temporal events, this is in essence what we had argued earlier, regarding the distinction of doctrinal gnosis and the ultimate gnosis it symbolizes. When he says that he certainly does not aim to correct the dogma of the Trinity, we most 1 [Editor’s Note]: The letters of Patrick Moore and of Gustavo Polit appeared in Volume 30 of this journal, at pp. -

The Deep Horizon

The Matheson Trust The Deep Horizon Stratford Caldecott "Wherever men and women discover a call to the absolute and transcendent, the metaphysical dimension of reality opens up before them: in truth, in beauty, in moral values, in other persons, in being itself, in God. We face a great challenge at the end of this millennium to move from phenomenon to foundation, a step as necessary as it is urgent. We cannot stop short at experience alone; even if experience does reveal the human being's interiority and spirituality, speculative thinking must penetrate to the spiritual core and the gound from which it rises. Therefore, a philosophy which shuns metaphysics would be radically unsuited to the task of mediation in the understanding of Revelation." [i] With such words as these, Pope John Paul II, in his 1998 encyclical letter on Faith and Reason addressed to the bishops of the Catholic Church, calls for a renewal of metaphysics, "because I am convinced that it is the path to be taken in order to move beyond the crisis pervading large sectors of philosophy at the moment, and thus to correct certain mistaken modes of behaviour now widespread in our society". He goes on, "Such a ground for understanding and dialogue is all the more vital nowadays, since the most pressing issues facing humanity - ecology, peace and the co-existence of different races and cultures, for instance - may possibly find a solution if there is a clear and honest collaboration between Christians and the followers of other religions and all those who, while not sharing a religious belief, have at heart the renewal of humanity" [section 104]. -

The Sense of the Supernatural Jean Borella

The Sense of the Supernatural Jean Borella Translated by G. John Champoux Preface Nature desires supernature Some fifty years ago Father de Lubac published Surnaturel: études historiques,1 and one of the major theological debates of the twentieth century sprang up around this book. Although almost completely ignored by the public, it occasioned radical confrontations between some of the most illustrious theologians of the Catholic Church. And rightly so, for it touches on what is essential. The learned Jesuit was not, as the modest subtitle announced, content with retracing the history of an idea, an idea as a matter of fact central to the organisation of Christian doctrine. He also went to work as a theologian to show that ecclesiastical tradition, except for the last two centuries, had never viewed the ideas of a ‘pure nature’ and a ‘pure supernature’ as two completely heteronomous realities. In particular he established that the affirmation of a natural desire for the supernatural, which is to say the vision of God, was to be found in St Thomas: ‘every intellect naturally desires the divine Substance’ (Summa Contra Gentiles III, 57). And in fact every being desires its own good for, without it, it cannot attain to its own perfection; thus the intellect, whose proper good is the Truth of that which is, necessarily aspires to the knowledge of That which absolutely is: ‘consequently, for perfect happiness, the intellect needs to reach the very Essence of the First Cause. And thus it will have its perfection through union with God as with that object’ (Summa Theologiae IaIIae, 3, 8). -

Christianity Islam

Christianity/Islam/Comparative Religion Frithjof Schuon Th is new edition of Frithjof Schuon’s classic work contains: Christianity a fully revised translation from the original French; an appendix of selections from letters and other previously unpublished writings; comprehensive editor’s notes and preface by James Cutsinger; Islam an index and glossary of terms. Perspectives on Esoteric Ecumenism “Schuon’s thought does not demand that we agree or disagree, A New Translation with Selected Letters but that we understand or do not understand. Such writing is of rare and lasting value.” —Times Literary Supplement C “I have met with no more impressive work in the comparative study of Oriental and hristianity Occidental religion.” —T. S. Eliot, Nobel laureate for literature, on Schuon’s fi rst book, Th e Transcendent Unity of Religions “[Schuon is] the most important religious thinker of our century.” —Huston Smith, author of Th e World’s Religions and Th e Soul of Christianity “In reading Schuon I have the impression that I am going along parallel to him, and once in a while I will get a glimpse of what he means in terms of my own tradition and experience.… I think that he has exactly the right view.… I appreciate him more and more.… I am grateful for the chance to be in contact with people like him.” —Th omas Merton (from a letter to Marco Pallis) / “[Schuon is] the leading philosopher of Islamic theosophical mysticism.” —Annemarie Schimmel, Harvard University I slam “[Th is] collection has some essays that will interest students engaged in the comparative study of … Islam and Christianity. -

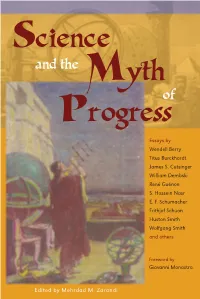

Science and the Myth of Progress Appears As One of Our Selections in the Perennial Philosophy Series

Religion/Philosophy of Science Zarandi Can the knowledge provided by modern science satisfy our need to know the most profound nature of reality and of humanity? Science “The great advantage of this book is that it puts together texts of authors (scientists, philosophers and theologians) whose lucidity about modern and the science goes far beyond emotional reaction and moralist subjectivity; and this ‘tour de force’ is accomplished from within the point of view of the Science yth main traditional religions. Here, Science and Faith are reconciled in an M unexpected way: scientific objectivity is not an issue; but the real issue, where one sees no proof of progress, is whether man is capable of using of modern science properly. A must for the reader who wants to sharpen his or her discernment about modern science.” —Jean-Pierre Lafouge, Marquette University rogress and the and P “Writing as an active research scientist, living in the present Culture of Disbelief created (partly unwittingly) by the science establishment, I can Essays by think of no Research and Development project more significant to the Wendell Berry future of humanity than putting ‘science’ back into its proper place as a Titus Burckhardt part of culture, but not its religion. This book is an excellent contribution Myth to that paramount goal.” James S. Cutsinger —Rustum Roy, Evan Pugh Professor of the Solid State, Emeritus, William Dembski Pennsylvania State University René Guénon “A wonderful collection of essays dealing with the supposed conflict S. Hossein Nasr between religion and science from both a scientific and a metaphysical of E. -

Sufism Veil and Quintessence by Frithjof Schuon

Islam/Sufi sm Schuon is revised and expanded edition of Frithjof Schuon’s Su sm: Veil and Quintessence contains: Sufi sm a new translation of this classic work; previously unpublished correspondence by Veil and Quintessence Frithjof Schuon; an editor’s preface by James S. Cutsinger; A New Translation with Selected Letters a new foreword by Seyyed Hossein Nasr; extensive editor’s notes by James S. Cutsinger; a glossary of foreign terms and phrases; an index; and biographical notes. Sufi sm: Veil sm: Veil Sufi “ is small book is a fascinating interpretation of Islam by the leading philosopher of Islamic theosophical mysticism. e book is an excellent introduction into the higher aspects of Su sm.” —Annemarie Schimmel, Harvard University “In this book one can discover with greater clarity than any other available work the distinction between that quintessential Su sm which comprises the very heart of the message of Su sm and the more exteriorized forms of Islam. No other work succeeds so well in removing the most formidable and notable impediments in the understanding of the authentic Su tradition for the Western reader.” and —Seyyed Hossein Nasr, the George Washington University Quintessence “Schuon’s thought does not demand that we agree or disagree, but that we understand or do not understand. Such writing is of rare and lasting value.” —Times Literary Supplement “If I were asked who is the greatest writer of our time, I would say Frithjof Schuon without hesitation.” —Martin Lings, author of Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources Frithjof Schuon, philosopher and metaphysician, is the best known proponent of the Perennial Philosophy. -

The Deep Horizon Stratford Caldecott

The Matheson Trust The Deep Horizon Stratford Caldecott "Wherever men and women discover a call to the absolute and transcendent, the metaphysical dimension of reality opens up before them: in truth, in beauty, in moral values, in other persons, in being itself, in God. We face a great challenge at the end of this millennium to move from phenomenon to foundation, a step as necessary as it is urgent. We cannot stop short at experience alone; even if experience does reveal the human being's interiority and spirituality, speculative thinking must penetrate to the spiritual core and the gound from which it rises. Therefore, a philosophy which shuns metaphysics would be radically unsuited to the task of mediation in the understanding of Revelation." [i] With such words as these, Pope John Paul II, in his 1998 encyclical letter on Faith and Reason addressed to the bishops of the Catholic Church, calls for a renewal of metaphysics, "because I am convinced that it is the path to be taken in order to move beyond the crisis pervading large sectors of philosophy at the moment, and thus to correct certain mistaken modes of behaviour now widespread in our society". He goes on, "Such a ground for understanding and dialogue is all the more vital nowadays, since the most pressing issues facing humanity - ecology, peace and the co- existence of different races and cultures, for instance - may possibly find a solution if there is a clear and honest collaboration between Christians and the followers of other religions and all those who, while not sharing a religious belief, have at heart the renewal of humanity" [section 104]. -

The Approach of the Traditionalist School to the Epistemological And

to work has not been n,.""./lnl in orin It is own work. from the or of other n",(1,nl'" been been cited Abstract. 3 Dedication. 6 Acknowledgements. 7 Introduction. 8 Traditionalist Chapter 1: The un"dl",\,t. Chapter 2: Knower and the in Metaphysical Intellection. 43 Traditionalist Spiritual Anthropology: Chapter 'Duo Sunt Homine'. 68 D6gringolade' . 94 Part III: Traditionalist ans;ceI10ent Unity of Religions. 128 Conclusion. 148 L>'VI",,",UYl/\. 1: The of Reality. Aldous and "v...... ,.,. School. 157 Bibliography. 2 Abstract: The present thesis vVF.U'., with an identification of the fact that numerous <11.'c:lkuvl111l.' commentators on the mystical ex!)enenc:e debate nmireTJiresent the epistemological position of the Traditionalist school; and I.,LLl'JU):~ a confusion of the mystical . P'Yt'lPMPnl"p with metaphysical intellection. thesis then sets out to this misperception through a detailed presentation (in chapters 1-3) ofthe epistemology of the Traditionalist school, viz.: (i) doctrine of a supra-individual Intellect, and of metaphysical and of their distinctness from reason, Revelation, and inspiration, respectively (chapter 1); (ii) foundational distinction between the Intellect and metaphysical intellection on the one hand, and the mystical experience on the other hand; and of the· direct not mediated or constructed nature supra-rational knowledge conferred in metaphysical intellection of the Intellect (chapter 2); and finally (iii) tripartite spiritual epistemology ofIntellect, reason, and the empirical "'''''''''''''''. respectively; -

EYE of the HEART a Journal of Traditional Wisdom

EYE of the HEART A Journal of Traditional Wisdom Issue 3, 2009 La Trobe University, Bendigo Eye of the Heart is a scholarly journal providing a forum for the exploration of the great philosophical and religious traditions. It addresses the inner meaning of philosophy and religion through elucidations of metaphysical, cosmological, and soteriological principles, and through a penetration of the forms preserved in each religious tradition. Eye of the Heart is published bi-annually. It is an Open Access Journal freely available online. A print version is available at cost value through La Trobe University, Campus Graphics (via the Eye of the Heart website). Unless otherwise stated all articles are original and have been peer-reviewed in accord with the Higher Education Research Data Collection (Australian Government, Department of Education, Science and Training) 2008 specifications. Contact: Editor, Eye of the Heart Arts Program, La Trobe University P.O. Box 199, Bendigo 3552, Australia Tel: +61 3 5444 7243; Fax: +61 3 5444 7970 Email: [email protected] Website: www.latrobe.edu.au/eyeoftheheart Publisher: La Trobe University, Bendigo Printed by Campus Graphics www.latrobe.edu.au/campusgraphics. Typeface is World Wisdom used by kind permission of World Wisdom Books www.worldwisdom.com. Cover: ‘Zodiac Man’ from the calendar pages of the Tres Riches Heures of Jean Duc de Berry, 15th Century, France. Copyright: © May, 2009. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials published in this issue are copyrighted by Eye of the Heart and the respective -

From Butler to Thornton

From Butler to Thornton: A Typology of Conflicting Readings of the Two Books of Scripture and Nature in the Church of England from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Century By Jeffrey Boldt A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Graduate Centre for Theological Studies of the Toronto School of Theology. In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Theology awarded by Wycliffe College and the University of Toronto. © Copyright by Jeffrey Boldt 2018 From Butler to Thornton: A Typology of Conflicting Readings of the Two Books of Scripture and Nature in the Church of England from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Century Jeffrey Boldt Doctor of Theology Wycliffe College and the University of Toronto 2018 ABSTRACT This dissertation studies the persistence within modern Anglicanism of (a) a classical "high view" of Scripture as the exemplar of creation, (b) the apologetic and phenomenological advantages of this view in the wake of Joseph Butler (1692-1752) due to (c) the kind of theodicy the Bible displays in contrast to more rationalistic proposals from deism to panentheism. (d) Finally, the view of theodicy and Scripture one takes influences whether or not one reads the two books of Scripture and nature figurally. The "high view" was undercut by nineteenth-century sectarian polemics between Protestants and Tractarians. Yet a minority kept this tradition alive. Lionel Thornton (1884-1960) is important to this project because he escaped from Tractarian and Protestant dead ends. The dissertation lays out this broader Anglican story and then focuses on Thornton, for whose work I provide historical context and a detailed examination. -

Letters to the Editor: an Exchange on Tradition and Sufism

Letters to the Editor: An Exchange on Tradition and Sufism The Malamatiyya, Sufism, and Traditionalist Orthodoxy: A Response to Samuel Bendeck Sotillos’ review of “Sufism and the Way of Blame by Yannis Toussulis” (Sacred Web, Volume 27) By Yannis Toussulis acred Web is a prestigious journal that has accumulated accolades S from a number of distinguished scholars such as Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Karen Armstrong, and Huston Smith. The journal’s contributors have included luminaries such as Frithjof Schuon, Ananda Coomaras- wamy, William C. Chittick, and a host of others. One would expect that a review of one’s book in such a journal would be non-prejudicial, but, sadly, I do not find this in Mr. Sotillos’ review. Sotillos does not confine himself to a factual critique of the history presented in my book, nor does he point out any logical inconsistencies in my arguments, nor does he offer a penetrating critique of the paradigm that I explore. Instead, the latter is dismissed out-of-hand as an “admix- ture of humanism and modern psychology.” This allegation is odd to me since I am known elsewhere as a critic of both of these intellectual movements despite the fact that I am trained as an academic psychologist. The only reason given for his preemptory dismissal of my work as humanistic and (presumably) psychologistic is that Sotillos disagrees with my conclusions that “the purpose of the malamati path is not perfec- tion in the attainment of the superhuman, but rather a greater human relatedness, greater transparency, and a deeper relationship to the divine” (p. -

An Examination of the Relationship Between Culturally Recognized Symbols As Avatars and Trust in Computer

AN EXAMINATION OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CULTURALLY RECOGNIZED SYMBOLS AS AVATARS AND TRUST IN COMPUTER- MEDIATED COMMUNICATION ENVIRONMENTS Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this dissertation is my own or was done in collaboration with my advisory committee. This dissertation does not include proprietary or classified information. ________________________________________ Rodger Glenn Morrison, Jr. Certificate of Approval: _________________________ _______________________ Houston H. Carr Casey G. Cegielski, Chair Professor Associate Professor Management Management _________________________ _______________________ R. Kelly Rainer, Jr. George T. Flowers George Phillips Privett Professor Dean Management Graduate School AN EXAMINATION OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CULTURALLY RECOGNIZED SYMBOLS AS AVATARS AND TRUST IN COMPUTER- MEDIATED COMMUNICATION ENVIRONMENTS Rodger Glenn Morrison, Jr. A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 19, 2008 AN EXAMINATION OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CULTURALLY RECOGNIZED SYMBOLS AS AVATARS AND TRUST IN COMPUTER- MEDIATED COMMUNICATION ENVIRONMENTS Rodger Glenn Morrison, Jr. Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this dissertation at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions and at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights. _____________________________ Signature of Author _____________________________ Date of Graduation iii AN EXAMINATION OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CULTURALLY RECOGNIZED SYMBOLS AS AVATARS AND TRUST IN COMPUTER- MEDIATED COMMUNICATION ENVIRONMENTS Rodger Glenn Morrison, Jr. Doctor of Philosophy, December 19, 2008 (M.B.A., Troy University, 2004) (B.S., Troy University, 1999) (A.A.S., Community College of the Air Force, 1992) 181 Typed Pages Directed by Casey G.