Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the Editor ne should thank Gustavo Polit for going to such length to point out O various confusions, oversights, errors, incomprehensions, and biases which he finds in our note responding to his and Patrick Moore’s letters.1 While some of Polit’s remarks arise from misunderstanding, and with many of them one can agree (so comprehensive is their scope), he does identify genuine disagreement between us. As for misunderstanding: One does not overlook the origin of modernity within Christendom, though this was not because of a lack of genuine gnosis within the Church, as again, Jean Borella has amply documented (Guenonian Esoterism and Christian Mystery). The point was simply that Christianity has in fact borne the brunt of the modernist attack: and in fact, has the persistence of jnana prevented the ongoing modernization of India? Again, one does not reduce the universal metaphysical Order to the formal orders as Polit fears: this would amount to eliding the Uncreated order and the formless spiritual order of Creation! And then, it is no intention of ours to diminish the scope and authority of spiritual intellect merely by referring it to the metaphysical orientation of spiritual life as evoked by Mr. Lakhani’s editorial in Volume 30 of Sacred Web. As for agreement: when Polit says that metaphysical doctrine can vary only in ‘formulation’, while its Truth stands invariant over temporal events, this is in essence what we had argued earlier, regarding the distinction of doctrinal gnosis and the ultimate gnosis it symbolizes. When he says that he certainly does not aim to correct the dogma of the Trinity, we most 1 [Editor’s Note]: The letters of Patrick Moore and of Gustavo Polit appeared in Volume 30 of this journal, at pp. -

Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2005 Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Daniels, B. (2005). Daniels, B. (2005). Nondualism and the divine domain. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 24(1), 1–15.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 24 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2005.24.1.1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels This paper claims that the ultimate issue confronting transpersonal theory is that of nondual- ism. The revelation of this spiritual reality has a long history in the spiritual traditions, which has been perhaps most prolifically advocated by Ken Wilber (1995, 2000a), and fully explicat- ed by David Loy (1998). Nonetheless, these scholarly accounts of nondual reality, and the spir- itual traditions upon which they are based, either do not include or else misrepresent the reve- lation of a contemporary spiritual master crucial to the understanding of nondualism. Avatar Adi Da not only offers a greater differentiation of nondual reality than can be found in contem- porary scholarly texts, but also a dimension of nondualism not found in any previous spiritual revelation. -

The Deep Horizon

The Matheson Trust The Deep Horizon Stratford Caldecott "Wherever men and women discover a call to the absolute and transcendent, the metaphysical dimension of reality opens up before them: in truth, in beauty, in moral values, in other persons, in being itself, in God. We face a great challenge at the end of this millennium to move from phenomenon to foundation, a step as necessary as it is urgent. We cannot stop short at experience alone; even if experience does reveal the human being's interiority and spirituality, speculative thinking must penetrate to the spiritual core and the gound from which it rises. Therefore, a philosophy which shuns metaphysics would be radically unsuited to the task of mediation in the understanding of Revelation." [i] With such words as these, Pope John Paul II, in his 1998 encyclical letter on Faith and Reason addressed to the bishops of the Catholic Church, calls for a renewal of metaphysics, "because I am convinced that it is the path to be taken in order to move beyond the crisis pervading large sectors of philosophy at the moment, and thus to correct certain mistaken modes of behaviour now widespread in our society". He goes on, "Such a ground for understanding and dialogue is all the more vital nowadays, since the most pressing issues facing humanity - ecology, peace and the co-existence of different races and cultures, for instance - may possibly find a solution if there is a clear and honest collaboration between Christians and the followers of other religions and all those who, while not sharing a religious belief, have at heart the renewal of humanity" [section 104]. -

The Milk of the Virgin: the Prophet, the Saint and the Sage by Renaud Fabbri

From the World Wisdom online library: www. worldwisdom.com/public/library/default.aspx The following essay is found in Sacred Web 20, edited by M. Ali Lakhani The Milk of the Virgin: The Prophet, the Saint and the Sage by Renaud Fabbri Prophets, saints, and sages: The prophet brings a form of faith — a religion; The saint lives it; the sage opens A luminous realm of Pure Spirit Beyond form. Prophets are also wise men, Yet about the highest Truth they speak softly; To the sage, holiness bestows light. God and our heart are united in eternity. (Frithjof Schuon)1 There have been a few controversies in the last decade about the teaching and personality of the 20th century Perennialist author and founder of the Maryamiyyah Sufi order, Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998), 1 Frithjof Schuon, Songs without Names XII / XVI (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2007). also known under the name of Sheikh Isa Nur Ad-Din Ahmad. These controversies have been reflected to various degrees in articles published by traditionalist journals as well as in recent scholarly publications. In the following paper, it will be argued that Frithjof Schuon is best understood neither as the founder of a new religion (a prophet in the classical sense of the word) nor as a Muslim saint, but as a universal sage, a spokesman for the religio perennis whose connection with Islam, although providential, remains secondary in the context of his message of esoterism, universality and primordiality. Before we engage in an attempt at defining a sage, we will need to refute two types of criticisms against Schuon. -

The Sense of the Supernatural Jean Borella

The Sense of the Supernatural Jean Borella Translated by G. John Champoux Preface Nature desires supernature Some fifty years ago Father de Lubac published Surnaturel: études historiques,1 and one of the major theological debates of the twentieth century sprang up around this book. Although almost completely ignored by the public, it occasioned radical confrontations between some of the most illustrious theologians of the Catholic Church. And rightly so, for it touches on what is essential. The learned Jesuit was not, as the modest subtitle announced, content with retracing the history of an idea, an idea as a matter of fact central to the organisation of Christian doctrine. He also went to work as a theologian to show that ecclesiastical tradition, except for the last two centuries, had never viewed the ideas of a ‘pure nature’ and a ‘pure supernature’ as two completely heteronomous realities. In particular he established that the affirmation of a natural desire for the supernatural, which is to say the vision of God, was to be found in St Thomas: ‘every intellect naturally desires the divine Substance’ (Summa Contra Gentiles III, 57). And in fact every being desires its own good for, without it, it cannot attain to its own perfection; thus the intellect, whose proper good is the Truth of that which is, necessarily aspires to the knowledge of That which absolutely is: ‘consequently, for perfect happiness, the intellect needs to reach the very Essence of the First Cause. And thus it will have its perfection through union with God as with that object’ (Summa Theologiae IaIIae, 3, 8). -

The Traces of the Bhagavad Gita in the Perennial Philosophy—A Critical Study of the Gita’S Reception Among the Perennialists

religions Article The Traces of the Bhagavad Gita in the Perennial Philosophy—A Critical Study of the Gita’s Reception Among the Perennialists Mohammad Syifa Amin Widigdo 1,2 1 Faculty of Islamic Studies, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta 55183, Indonesia; [email protected] 2 Wonderhome Library, Yogyakarta 55294, Indonesia Received: 14 April 2020; Accepted: 28 April 2020; Published: 6 May 2020 Abstract: This article studies the reception of the Bhagavad Gita within circles of Perennial Philosophy scholars and examines how the Gita is interpreted to the extent that it influenced their thoughts. Within the Hindu tradition, the Gita is often read from a dualist and/or non-dualist perspective in the context of observing religious teachings and practices. In the hands of Perennial Philosophy scholars, the Gita is read from a different angle. Through a critical examination of the original works of the Perennialists, this article shows that the majority of the Perennial traditionalists read the Gita from a dualist background but that, eventually, they were convinced that the Gita’s paradigm is essentially non-dualist. In turn, this non-dualist paradigm of the Gita influences and transforms their ontological thought, from the dualist to the non-dualist view of the reality. Meanwhile, the non-traditionalist group of Perennial Philosophy scholars are not interested in this ontological discussion. They are more concerned with the question of how the Gita provides certain ways of attaining human liberation and salvation. Interestingly, both traditionalist and non-traditionalist camps are influenced by the Gita, at the same time, inserting an external understanding and interpretation into the Gita. -

6 'Mystic Hinduism9 Vedanta and the Politics of Representation

'Mystic Hinduism' 119 Locating the 'essence' of the Hindu tradition in origins (arche), in this case the ancient Vedas, however, was also prevalent among the nineteenth- century Hindu reformers as a nationalist and anti-colonial stratagem. For 9 Dayananda Saraswati and the Arya Samaj, for instance, the Samhitas were 6 'Mystic Hinduism the source of all legitimate manifestations of Hinduism and also provided evidence of the superiority of Hinduism over 'younger' religions such as Vedanta and the politics of Christianity. For Saraswati, Christianity was a poor imitation of the Hindu representation religion. Indeed, all knowledge, he believed, could be demonstrated to have originated in Mother India from time immemorial, including modern tech- nologies such as aircraft, long-forgotten and now claimed to be the sole invention of the colonizing Westerners. Equally, since William Jones had established an Indo-European link between Sanskrit and the classical languages of European culture, interest in comparative linguistics had devel- oped steadily among Orientalists and the search for a common They assert that the world is nothing but an illusion, a dream, a magic spell, Indo-European source most often turned its attentions eastwards. Saraswati and that the bodies, in order to be truly existent, have to cease existing in explicitly identified this 'Ur-language' with Vedic Sanskrit, now conceived as themselves, and to merge into nothingness, which due to its simplicity the 'mother of all languages'. This approach, of course, intersected well with amounts to the perfection of all beings. They claim that saintliness consists Romantic representations of India as the geographical point of origin of in willing nothing, thinking nothing, feeling nothing .. -

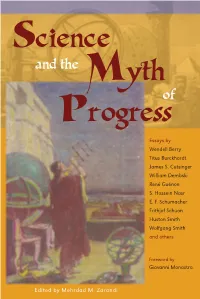

Science and the Myth of Progress Appears As One of Our Selections in the Perennial Philosophy Series

Religion/Philosophy of Science Zarandi Can the knowledge provided by modern science satisfy our need to know the most profound nature of reality and of humanity? Science “The great advantage of this book is that it puts together texts of authors (scientists, philosophers and theologians) whose lucidity about modern and the science goes far beyond emotional reaction and moralist subjectivity; and this ‘tour de force’ is accomplished from within the point of view of the Science yth main traditional religions. Here, Science and Faith are reconciled in an M unexpected way: scientific objectivity is not an issue; but the real issue, where one sees no proof of progress, is whether man is capable of using of modern science properly. A must for the reader who wants to sharpen his or her discernment about modern science.” —Jean-Pierre Lafouge, Marquette University rogress and the and P “Writing as an active research scientist, living in the present Culture of Disbelief created (partly unwittingly) by the science establishment, I can Essays by think of no Research and Development project more significant to the Wendell Berry future of humanity than putting ‘science’ back into its proper place as a Titus Burckhardt part of culture, but not its religion. This book is an excellent contribution Myth to that paramount goal.” James S. Cutsinger —Rustum Roy, Evan Pugh Professor of the Solid State, Emeritus, William Dembski Pennsylvania State University René Guénon “A wonderful collection of essays dealing with the supposed conflict S. Hossein Nasr between religion and science from both a scientific and a metaphysical of E. -

The Return of the Perennial Philosophy. the Supreme Vision of Western Esotericism

The Return of the Perennial Philosophy. The Supreme Vision of Western Esotericism By John Holman. Watkins Publishing, 1st edition London 2008. Paperback, 172 pp. Review by Roland Benedikter This book tries to provide a short integrative picture of the Western esoteric worldview, seen as the historical basis of contemporary “experiential” spirituality. Holman’s main hypothesis is that in the present epoch of a broad renaissance of traditional religion it is increasingly becoming necessary to know the main themes and features of the “empirical spirituality” of the West that have long been hidden in the background of its public sphere. “Empirical spirituality” is conceived as being opposed to mere “faith” and dedicated instead to “spiritual research” and “exploration” in “first person.” To identify what the common ground (or the “supreme vision”) of the very different Western esoteric streams has been in the last seven centuries shall enable the reader to help prepare the present culture of secular rationality for the “return of the perennial philosophy,” and thus for a more balanced societal paradigm. “Perennial philosophy” is outlined as an experimental proceeding of opening up new empirical knowledge between realism and transcendentalism. According to Holman, this proceeding has always been equipped with certain methodological tools common to more or less all Western esoteric traditions in order to create experiential alternatives to collectivistic, myth-oriented religion. The book consists of an introduction and three main parts divided in 13 chapters. The Introduction gives a brief overview of the studies carried out so far about the field mainly by means of a critical history of ideas, and depicts the “ethnomethodological” approach chosen by the author. -

The Deep Horizon Stratford Caldecott

The Matheson Trust The Deep Horizon Stratford Caldecott "Wherever men and women discover a call to the absolute and transcendent, the metaphysical dimension of reality opens up before them: in truth, in beauty, in moral values, in other persons, in being itself, in God. We face a great challenge at the end of this millennium to move from phenomenon to foundation, a step as necessary as it is urgent. We cannot stop short at experience alone; even if experience does reveal the human being's interiority and spirituality, speculative thinking must penetrate to the spiritual core and the gound from which it rises. Therefore, a philosophy which shuns metaphysics would be radically unsuited to the task of mediation in the understanding of Revelation." [i] With such words as these, Pope John Paul II, in his 1998 encyclical letter on Faith and Reason addressed to the bishops of the Catholic Church, calls for a renewal of metaphysics, "because I am convinced that it is the path to be taken in order to move beyond the crisis pervading large sectors of philosophy at the moment, and thus to correct certain mistaken modes of behaviour now widespread in our society". He goes on, "Such a ground for understanding and dialogue is all the more vital nowadays, since the most pressing issues facing humanity - ecology, peace and the co- existence of different races and cultures, for instance - may possibly find a solution if there is a clear and honest collaboration between Christians and the followers of other religions and all those who, while not sharing a religious belief, have at heart the renewal of humanity" [section 104]. -

Beyond Theology

BEYOND THEOLOGY “Mysticism and the Perennial Philosophy” (#109) Host: Have you ever heard of the perennial philosophy? Do you know what it is? Stay tuned and see how it relates to the mystic’s vision. Announcer: Production funding for this program has been provided in part by the Shumaker Family Foundation – promoting social and environmental justice, education, spirituality and the arts. Host: With innovations in transportation and communication, the world has in effect become a smaller place than it used to be. It’s easier for people to travel and to see what’s happening in other parts of the world. In the process, people of different religious faiths have been rubbing shoulders with each other more often and sometimes coming into conflict. This has stimulated a greater interest in the study of other religions. Huston Smith published a well-known text on world religions back in 1958. In this program, we explore the views of this mystic philosopher and his perennial quest for truth. Huston Smith (Emeritus Professor of Philosophy and Religion): From as far back as I can remember, what I most wanted … outside of family and the intimacy there … was truth, but with a capital T -- The Truth about the ultimate nature of reality. Narrator: Born in China in the spring of 1919, Huston Smith grew up in a rural Chinese community, where his parents served as missionaries for the Methodist Church. Huston Smith: Yes. My parents were missionaries. And actually, I'm third generation of missionary parents because she was born in China, too, of missionary parents that went out in the 19th century. -

Perennism and Spiritual Knowledges

82 Australian Religion Studies Review NOT THE NEW AGE: PERENNISM AND SPIRITUAL KNOWLEDGES Adam PossamaY University of Western Sydney People who would commonly be called New Agers refuse this appellation; they even disagree with any label. The aim of this article is to give a voice to these people by working on a common thread. This thread is found across 35 so-called New Agers and gives support to a heuristic concept which I call perennism and which I define as a syncretic and tolerant spirituality which interprets the world as Monistic and whose actors are attempting to develop their Human Potential Ethic by seeking Spiritual Knowledge, mainly that of the Self While researching for this conceptualisation, it will also be argued that the 'New Age' phenomenon is an innovative form of esotericism, at least in its every day life practice, and is thus a new genre of spirituality. During 1996-1997, I interviewed 35 Melburnians who would "commonly" be described as New Agers. The participants were selected through 'network sampling', that is I was selecting my participants while networking in the milieu. They were involved in many spiritual practices, however each of them tended to specialise in one specific type of activity, such as astrology, automatic writing, Buddhism, channelling, crystals manipulation, feminist spirituality, meditation, naturopathy, numerology_, palmistry, Reiki, spiritualism, Tantrism, tarot, or urban shamanism. This list, actually, understates the diversity of practice. At the beginning of each interview, I asked the participants how they followed their particular spiritual path (or spiritual journey). Other questions were: What are the resources you have employed or employ to follow this path? What groups are you going to? What are you studying? What books are you reading? What techniques or meditations are you using? ..