The Seventh Ecumenical Council and the Veneration of Icons in Orthodoxy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures by Sean Delaine Griffin 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle by Sean Delaine Griffin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Gail Lenhoff, Chair The monastic chroniclers of medieval Rus’ lived in a liturgical world. Morning, evening and night they prayed the “divine services” of the Byzantine Church, and this study is the first to examine how these rituals shaped the way they wrote and compiled the Povest’ vremennykh let (Primary Chronicle, ca. 12th century), the earliest surviving East Slavic historical record. My principal argument is that several foundational accounts of East Slavic history—including the tales of the baptism of Princess Ol’ga and her burial, Prince Vladimir’s conversion, the mass baptism of Rus’, and the martyrdom of Princes Boris and Gleb—have their source in the feasts of the liturgical year. The liturgy of the Eastern Church proclaimed a distinctively Byzantine myth of Christian origins: a sacred narrative about the conversion of the Roman Empire, the glorification of the emperor Constantine and empress Helen, and the victory of Christianity over paganism. In the decades following the conversion of Rus’, the chroniclers in Kiev learned these narratives from the church services and patterned their own tales of Christianization after them. The ii result was a myth of Christian origins for Rus’—a myth promulgated even today by the Russian Orthodox Church—that reproduced the myth of Christian origins for the Eastern Roman Empire articulated in the Byzantine rite. -

OCTOECHOS – DAY of the WEEK Tone 1 – 1St Canon – Ode 3

OCTOECHOS – DAY OF THE WEEK Tone 1 – 1st Canon – Ode 3 – Hymn to the Theotokos You conceived God in your womb through the Holy Spirit, and yet remained unconsumed, O Virgin. The bush unconsumed by the fire clearly foretold you to the lawgiver Moses for you received the Fire that cannot be endured. Monday – Vespers / Tuesday - Matins: Aposticha – Tone 1 O VIRGIN, WORTHY OF ALL PRAISE: MOSES, WITH PROPHETIC EYES, BEHELD THE MYSTERY THAT WAS TO TAKE PLACE IN YOU, AS HE SAW THE BUSH THAT BURNED, YET WAS NOT CONSUMED; FOR, THE FIRE OF DIVINITY DID NOT CONSUME YOUR WOMB, O PURE ONE. THEREFORE, WE PRAY TO YOU AS THE MOTHER OF GOD, // TO ASK PEACE, AND GREAT MERCY FOR THE WORLD. Tone 2 – Saturday Vespers & Friday Vespers (repeated) – Dogmaticon Dogmatic THE SHADOW OF THE LAW PASSED WHEN GRACE CAME. AS THE BUSH BURNED, YET WAS NOT CONSUMED, SO THE VIRGIN GAVE BIRTH, YET REMAINED A VIRGIN. THE RIGHTEOUS SUN HAS RISEN INSTEAD OF A PILLAR OF FLAME.// INSTEAD OF MOSES, CHRIST, THE SALVATION OF OUR SOULS. Tone 3 – Wed Matins – 2nd Aposticha ON THE MOUNTAIN IN THE FORM OF A CROSS, MOSES STRETCHED OUT HIS HANDS TO THE HEIGHTS AND DEFEATED AMALEK. BUT WHEN YOU SPREAD OUT YOUR PALMS ON THE PRECIOUS CROSS, O SAVIOUR, YOU TOOK ME IN YOUR EMBRACE, SAVING ME FROM ENSLAVEMENT TO THE FOE. YOU GAVE ME THE SIGN OF LIFE, TO FLEE FROM THE BOW OF MY ENEMIES. THEREFORE, O WORD, // I BOW DOWN IN WORSHIP TO YOUR PRECIOUS CROSS. Tone 4 – Irmos of the First Canon – for the Resurrection (Sat Night/Sun Morn) ODE ONE: FIRST CANON IRMOS: IN ANCIENT TIMES ISRAEL WALKED DRY-SHOD ACROSS THE RED SEA, AND MOSES, LIFTING HIS HAND IN THE FORM OF THE CROSS, PUT THE POWER OF AMALEK TO FLIGHT IN THE DESERT. -

BYZANTINE CAMEOS and the AESTHETICS of the ICON By

BYZANTINE CAMEOS AND THE AESTHETICS OF THE ICON by James A. Magruder, III A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland March 2014 © 2014 James A. Magruder, III All rights reserved Abstract Byzantine icons have attracted artists and art historians to what they saw as the flat style of large painted panels. They tend to understand this flatness as a repudiation of the Classical priority to represent Nature and an affirmation of otherworldly spirituality. However, many extant sacred portraits from the Byzantine period were executed in relief in precious materials, such as gemstones, ivory or gold. Byzantine writers describe contemporary icons as lifelike, sometimes even coming to life with divine power. The question is what Byzantine Christians hoped to represent by crafting small icons in precious materials, specifically cameos. The dissertation catalogs and analyzes Byzantine cameos from the end of Iconoclasm (843) until the fall of Constantinople (1453). They have not received comprehensive treatment before, but since they represent saints in iconic poses, they provide a good corpus of icons comparable to icons in other media. Their durability and the difficulty of reworking them also makes them a particularly faithful record of Byzantine priorities regarding the icon as a genre. In addition, the dissertation surveys theological texts that comment on or illustrate stone to understand what role the materiality of Byzantine cameos played in choosing stone relief for icons. Finally, it examines Byzantine epigrams written about or for icons to define the terms that shaped icon production. -

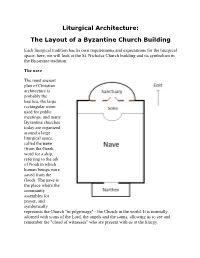

Liturgical Architecture: the Layout of a Byzantine Church Building

Liturgical Architecture: The Layout of a Byzantine Church Building Each liturgical tradition has its own requirements and expectations for the liturgical space; here, we will look at the St. Nicholas Church building and its symbolism in the Byzantine tradition. The nave The most ancient plan of Christian architecture is probably the basilica, the large rectangular room used for public meetings, and many Byzantine churches today are organized around a large liturgical space, called the nave (from the Greek word for a ship, referring to the ark of Noah in which human beings were saved from the flood). The nave is the place where the community assembles for prayer, and symbolically represents the Church "in pilgrimage" - the Church in the world. It is normally adorned with icons of the Lord, the angels and the saints, allowing us to see and remember the "cloud of witnesses" who are present with us at the liturgy. At St. Nicholas, the nave opens upward to a dome with stained glass of the Eucharist chalice and the Holy Spirit above the congregation. The nave is also provided with lights that at specific times the church interior can be brightly lit, especially at moments of great joy in the services, or dimly lit, like during parts of the Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts. The nave, where the congregation resides during the Divine Liturgy, at St. Nicholas is round, representing the endlessness of eternity. The principal church building of the Byzantine Rite, the Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, employed a round plan for the nave, and this has been imitated in many Byzantine church buildings. -

The Apocryphal Bulgarian Sermon of Saint John Chrysostom on the Оrigin of Paulicians and Manichean Dimensions of Medieval Paulician Identity

Studia Ceranea 10, 2020, p. 425–444 ISSN: 2084-140X DOI: 10.18778/2084-140X.10.21 e-ISSN: 2449-8378 Hristo Saldzhiev (Stara Zagora) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4116-6600 The Apocryphal Bulgarian Sermon of Saint John Chrysostom on the Оrigin of Paulicians and Manichean Dimensions of Medieval Paulician Identity ne of the most interesting documents concerning the early history of Pau- O licianism in Bulgarian lands is the apocryphal Saint John Chrysostom’s ser- mon on how the Paulicians came to be1. Its text is known entirely or partly from eight copies; the earliest ones are dated back to the 16th century2. The best-known variant is the copy from the Adžar collection N326 (17th century), preserved at the Bulgarian National Library3. It was found and published for the first time by Jor- dan Ivanov, the discoverer of the sermon, in 1922. Since then the Adžar and other copies have been published or quoted in different studies and research works4. The meaningful differences between the different copies are insignificant, except for the final passage. According to the Adžar copy, St. John Chrysostom from Petrič went to the Bulgarian land to search for the two “disciples of the devil”, but accord- ing to the others, he sent to the Bulgarian land delegates who brought “disciples of the devil” to Petrič5. That gives a reason to think that the copies transmitted the text of the initial original relatively correctly. According to Anisava Miltenova 1 Below in the text I will refer to it as “the sermon”. 2 А. МИЛТЕНОВА, Разобличението на дявола-граматик. -

Conceptualizing Angeloi in the Roman Empire. by Rangar Cline. (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 172.) Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2011

Numen 60 (2013) 135–154 brill.com/nu Ancient Angels: Conceptualizing Angeloi in the Roman Empire. By Rangar Cline. (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 172.) Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2011. xviii + 181 pp. ISBN 978–9004194533 (hbk.) The theme of the book is veneration of angels in religions in late antiquity (ca. 150–ca. 450 c.e.). Rangar Cline consults a wealth of archaeological and lit- erary evidence and shows that there was a shared terminology for angels in the Roman Empire, which implies that the term angelos was used across religions. Angeloi designate intermediate beings, beings that were believed to exist between gods and humans. Traditionally, they were thought to be present at springs, wells, and fountains, and they could be contacted by means of rituals, amulets, and invocations. The veneration of these beings took diffferent forms in diffferent regions and cultural contexts. The book has a preface, six chapters, and a conclusion, and includes pic- tures. In chapter one (“Introduction: The Words of Angels”), Cline defijines angels and gives a survey of the pagan-Christian discourse on them by means of the writings of Origen of Alexandria and Augustine of Hippo. Cline suggests that “the prominence of angeli in early Christianity is due to the success of early Christian authorities in defijining a system of orthodox Christian beliefs about, and attitudes towards, angeli that were distinct from non-Christian, and other Christian, beliefs about such beings” (p. 2). In addition to the term ange- los, Cline also presents a critical discussion of the use of the terms “Hellenism,” “monotheism,” and “polytheism.” Cline’s study of angels builds on Glenn Bow- ersock’s approach to Hellenism and Greek language in late antiquity: Bower- sock saw Hellenism as a possibility to give local expressions a more eloquent and cosmopolitan form. -

Course Listing Hellenic College, Inc

jostrosky Course Listing Hellenic College, Inc. Academic Year 2020-2021 Spring Credit Course Course Title/Description Professor Days Dates Time Building-Room Hours Capacity Enrollment ANGK 3100 Athletics&Society in Ancient Greece Dr. Stamatia G. Dova 01/19/2105/14/21 TBA - 3.00 15 0 This course offers a comprehensive overview of athletic competitions in Ancient Greece, from the archaic to the hellenistic period. Through close readings of ancient sources and contemporary theoretical literature on sports and society, the course will explore the significance of athletics for ancient Greek civilization. Special emphasis will be placed on the Olympics as a Panhellenic cultural institution and on their reception in modern times. ARBC 6201 Intermediate Arabic I Rev. Edward W. Hughes R 01/19/2105/14/21 10:40 AM 12:00 PM TBA - 1.50 8 0 A focus on the vocabulary as found in Vespers and Orthros, and the Divine Liturgy. Prereq: Beginning Arabic I and II. ARTS 1115 The Museums of Boston TO BE ANNOUNCED 01/19/2105/14/21 TBA - 3.00 15 0 This course presents a survey of Western art and architecture from ancient civilizations through the Dutch Renaissance, including some of the major architectural and artistic works of Byzantium. The course will meet 3 hours per week in the classroom and will also include an additional four instructor-led visits to relevant area museums. ARTS 2163 Iconography I Mr. Albert Qose W 01/19/2105/14/21 06:30 PM 09:00 PM TBA - 3.00 10 0 This course will begin with the preparation of the board and continue with the basic technique of egg tempera painting and the varnishing of an icon. -

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God George Contis M.D

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides Spirituality through Art 2015 Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God George Contis M.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_exhibitguides Recommended Citation Contis, George M.D., "Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God" (2015). Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides. 5. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_exhibitguides/5 This Exhibit Guide is brought to you for free and open access by the Spirituality through Art at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God by George Contis, M.D., M.P.H . Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God by George Contis, M.D., M.P.H. Booklet created for the exhibit: Icons from the George Contis Collection Revelation Cast in Bronze SEPTEMBER 15 – NOVEMBER 13, 2015 Marian Library Gallery University of Dayton 300 College Park Dayton, Ohio 45469-1390 937-229-4214 All artifacts displayed in this booklet are included in the exhibit. The Nativity of Christ Triptych. 1650 AD. The Mother of God is depicted lying on her side on the middle left of this icon. Behind her is the swaddled Christ infant over whom are the heads of two cows. Above the Mother of God are two angels and a radiant star. The side panels have six pairs of busts of saints and angels. Christianity came to Russia in 988 when the ruler of Kiev, Prince Vladimir, converted. -

Medieval Music for St. John the Baptist from the Royal

Medieval Music for St. John the Baptist from the Royal Convents of Sigena (Hospitallers) and Las Huelgas (Cistercians) CANTRIX —— Medieval Music for —— Mittelalterliche Musik für —— Musique médiévale pour St. John the Baptist from Johannes den Täufer aus den St-Jean-Baptiste dans the Royal Convents of königlichen Frauen klöstern von les couvents royaux de Sigena Sigena (Hospitallers) and Sigena (Hospitaliterinnen) und (Hospitalières) et Las Huelgas Las Huelgas (Cistercians) Las Huelgas (Zisterzienserinnen) (Cisterciennes) Agnieszka Budzińska-Bennett (AB) — voice, harp, direction / Gesang, Harfe, Leitung / voix, harpe, direction Kelly Landerkin (KL) — voice / Gesang / voix Lorenza Donadini (LD) — voice / Gesang / voix Hanna Järveläinen (HJ) — voice / Gesang / voix Eve Kopli (EK) — voice / Gesang / voix Agnieszka M. Tutton (AT) — voice / Gesang / voix Baptiste Romain (BR) — vielle, bells / Vielle, Glocken / vielle, cloches Mathias Spoerry (MS) — voice / Gesang / voix Instrumente / Instruments Vielle (13th c.) — Roland Suits, Tartu (EE), 2006 Vielle (14th c.) — Judith Kra , Paris (F), 2007 Romanesque harp — Claus Henry Hüttel, Düren (D), 2001 Medieval bells — Michael Metzler, Berlin (D), 2012 Medieval Music for St. John the Baptist from the Royal Convents CANTRIX of Sigena (Hospitallers) and Las Huelgas (Cistercians) 1. Mulierium hodie/INTER NATOS 9. Benedicamus/Hic est enim precursor motet, Germany, 14th c. Benedicamus trope, Huelgas, 13th–14th c. AT, LD, EK (motetus), AB, HJ, KL (tenor), AB & HJ (trope), LD, EK, AT 01:44 BR (bells) 02:00 10. Peire Vidal – S’ieu fos en cort 2. Inter natos V. Hic venit/Preparator veritatis troubadour song, Aquitaine, 12th c. responsorium with prosula, Sigena, 14th–15th c. MS, BR (vielle) 07:04 HJ (verse), AB & LD (prosula), KL, EK, AT 04:04 11. -

& What You Can Do to Help… Why It Has Endured 2000 Years …

Seeking and Understanding your Religious Heritage Why it has endured 2000 years …. & What you can do to help… WEAVING THE FABRIC OF HISTORY Το έργο αυτό έρχεται να συμπληρώσει και να αναδείξει την πίστη των χριστιανών μιας ιστορικής και πολιτιστικής κληρονομίας 2000 και πλέων ετών . Για αυτό και πρέπει να διατηρηθεί και να αντέξει στους αιώνες των αιώνων . Οι κτήτορες αυτού του Ιερού Ναού θα μείνουν στην ιστορία και θα τους μνημονεύουν αιωνίως . Θα καμαρώνουν τα εγγόνια τους , οι συγγενείς τους και οι επόμενες γενιές για την συμβολή τους σε αυτό το Έργο . Που είναι καταφύγιο και αποκούμπι για τις κακουχίες και τις θεομηνίες των καιρών μας. Θα μείνουμε στην μνήμη των συγγενών μας ως πρωτοπόροι και θεμελιωτές μια αντάξιας προσπάθειας συνεχίσεως της ιστορικής βυζαντινής κληρονομιάς των προγόνων μας. Τέλος όλοι μπορούν και πρέπει να συμβάλουν στην ανέγερση του Ιερού Ναού για την συνέχιση της Ιστορίας και τις Ορθοδοξίας. This Authentic Basilica complements and highlights Christian beliefs that have a historical, cultural and religious heritage of 2000 years and more. We have been given the responsibility to continue this legacy and help it to endure for centuries to come. The faithful that have and will continue to contribute to help build this holy temple will be remembered in history. The benefactors of this historic project will bestow upon their children and grandchildren for many generations the opportunity to become the torch bearers of Christendom. HOLY RELICS SOLEA Sanctuary NAVE Dedication or Sponsoring opportunities for Bell Tower Bell Tower- three- tiered Bell Tower $100,000.00 (Donors will have individual recognition both upstairs and downstairs on interior walls of Bell Tower) Bell Tower Elevator Handicap Accessible $150,000.00 (Donor will have individual recognition outside elevator as well as inside elevator) Bell Large $ 14,000.00 Bell Medium $ 9,000.00 Bell Small $ 6,000.00 (Donors will have their names engraved on bells.) The three bells will be made in Romania. -

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople1

STEFANOS ATHANASIOU The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople1 A Religious Minority and a Global Player Introduction In the extended family of the Orthodox Church of the Byzantine rite, it is well known that the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople takes honorary prece- dence over all other Orthodox autocephalous and autonomous churches.2 The story of its origins is well known. From a small church on the bay of the Bos- porus in the fishing village of Byzantium, to the centre of Eastern Christianity then through the transfer of the Roman imperial capital from Rome to Constantinople in the fourth century, and later its struggle for survival in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. Nevertheless, a discussion of the development of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople is required to address the newly- kindled discussion between the 14 official Orthodox autocephalous churches on the role of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in today’s Orthodox world. A recalling of apposite historical events is relevant to this discussion. As Karl Löwith remarks, “[H]istorical consciousness can only begin with itself, although its intention is to visualise the thinking of other times and other people. History must continually be recalled, reconsidered and re-explored by each current living generation” (Löwith 2004: 12). This article should also be understood with this in mind. It is intended to awaken old memories for reconsideration and reinterpretation. Since the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Ecumenical Patriarchate has taken up the role of custodian of the Byzantine tradition and culture and has lived out this tradition in its liturgical life in the region of old Byzantium (Eastern Roman Empire) and then of the Ottoman Empire and beyond.