Peasant Identities in Russia's Turmoil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Programme

FINAL PROGRAMME Friday, 12 June 2015 8.00-9.00 Registration 9.00-9.30 Welcome Address/Opening ceremony Chairs: S. Cicėnas (Vilnius, Lithuania) Minister of health of the Republic of Lithuania (Vilnius, Lithuania) Rector of Vilnius University (Vilnius, Lithuania) Dean of the Faculty of Medicine Vilnius University (Vilnius, Lithuania) Director of the Nacional Cancer Institute (Vilnius, Lithuania) 9.30 – 11.00 SESSION I Chairs: J. Niklinski (Bialystok, Poland), K. Sužiedėlis (Vilnius, Lithuania) 9.30-11.00 Bialystok Medical Academy – Research Group (Bialystok, Poland) Chairs: Prof. Jacek Niklinski, Prof. Lech Chyczewski Immune system and lung cancer: friends or foes? M. Moniuszko Science fiction or science reality - microRNA replacement therapy Anna Rusek The role of transcription factor Sox2 in cancer biology A. Eljaszewicz Recent guidelines for the diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer- diagnostic challenges and problems J. Reszec Metabolomic profiling of non-small cell lung cancer J. Kisluk 11.00 - 11.30 Lung cancer in women and never smokers S. Novello (Turin, Italy) 11.30 - 12.00 Coffee break 12.00 –13.00 AstraZeneca Satellite Symposium Chair: S. Cicėnas (Vilnius, Lithuania) 13.00-14.00 Lunch 14.00 – 16.40 Scientific session II Chairs: R. Pirker (Vienna, Austria), E. Danila (Vilnius, Lithuania). 14.00-14.40 Bevacizumab in treatment of NSCLC: preferred chemo partners F. De Marinis (Milan, Italy) 14.40-15.00 Lung Cancer Screening – Radiological Opportunities and Challenges S. Sudarski (Mannheim, Germany) 15.00-15.20 Tobacco control strategies M. Neuberger (Vienna, Austria) 15.20-15.40 Lung cancer screening by spiral CT M. Silva (Milano, Italy) 15.40-16.00 Biomarkers for chemotherapy in NSCLC J.B. -

Marx and History: the Russian Road and the Myth of Historical Determinism

Ciências Sociais Unisinos 57(1):78-86, janeiro/abril 2021 Unisinos - doi: 10.4013/csu.2021.57.1.07 Marx and history: the Russian road and the myth of historical determinism Marx e a história: a via russa e o mito do determinismo histórico Guilherme Nunes Pires1 [email protected] Abstract This paper aims to point out the limits of the historical determinism thesis in Marx’s thought by analyzing his writings on the Russian issue and the possibility of a “Russian road” to socialism. The perspective of historical determinism implies that Marx’s thought is supported by a unilinear view of social evolution, i.e. history is understood as a succes- sion of modes of production and their internal relations inexorably leading to a classless society. We argue that in letters and drafts on the Russian issue, Marx opposes to any attempt associate his thought with a deterministic conception of history. It is pointed out that Marx’s contact with the Russian populists in the 1880s provides textual ele- ments allowing to impose limits on the idea of historical determinism and the unilinear perspective in the historical process. Keywords: Marx. Historical Determinism. Unilinearity. Russian Road. Resumo O objetivo do presente artigo é apontar os limites da tese do determinismo histórico no pensamento de Marx, através da análise dos escritos sobre a questão russa e a possibilidade da “via russa” para o socialismo. A perspectiva do determinismo histórico compreende que o pensamento de Marx estaria amparado por uma visão unilinear da evolução social, ou seja, a história seria compreendida por uma sucessão de modos de produção e suas relações internas que inexoravelmente rumaria a uma sociedade sem classes sociais. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

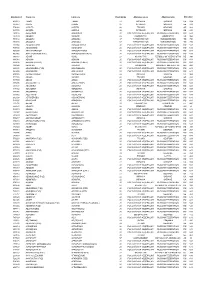

FÁK Állomáskódok

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

USSR and Lenin/Stalin)

Topic 3: The Rise and Rule of Single-Party States (USSR and Lenin/Stalin) Pipes Chapter 4 Major Theme: Origins and Nature of Authoritarian and Single-Party States Conditions That Produced Single-Party States Economic conditions inspire rebellion and anger in the people: The winter of 1916-1917 is very cold, which means that delivery of food and fuel is delayed, causing shortages. Fuel shortages close factories, leaving thousands of workers without a job. When the temperatures heat up, people go outside and there is a demonstration feb 23. Znamenskii square is the spark that leads to anarchy and the destruction of the government. After the Duma and the Soviet take over, the tsar has no control. Then the duality of the government made it very weak, because they had different objectives and no power to assemble the National Assembly, which led to unhappy people and made Bolshevik overthrow of a disorganized and weak government easy. The fact that the government also destroyed all systems of administration and then did not institute new ones made it powerless. In an effort for a truly democratic government, they failed to represent 80% of the population, and give themselves any real control. There was a focus on breaking down the old regime, but not building a new one. Emergence of Leaders: Aims, Ideology, Support Alexander Shliapnikov: Leading Bolshevik in Petrograd. Will be the first Soviet Commissar of Labor. Says that the “revolution” is based off of hunger and shortages. It will not last. Prince G. E. Lvov: Provisional government chair. Civic activist, who could represent the society. -

Download File

Cultural Experimentation as Regulatory Mechanism in Response to Events of War and Revolution in Russia (1914-1940) Anita Tárnai Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Anita Tárnai All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cultural Experimentation as Regulatory Mechanism in Response to Events of War and Revolution in Russia (1914-1940) Anita Tárnai From 1914 to 1940 Russia lived through a series of traumatic events: World War I, the Bolshevik revolution, the Civil War, famine, and the Bolshevik and subsequently Stalinist terror. These events precipitated and facilitated a complete breakdown of the status quo associated with the tsarist regime and led to the emergence and eventual pervasive presence of a culture of violence propagated by the Bolshevik regime. This dissertation explores how the ongoing exposure to trauma impaired ordinary perception and everyday language use, which, in turn, informed literary language use in the writings of Viktor Shklovsky, the prominent Formalist theoretician, and of the avant-garde writer, Daniil Kharms. While trauma studies usually focus on the reconstructive and redeeming features of trauma narratives, I invite readers to explore the structural features of literary language and how these features parallel mechanisms of cognitive processing, established by medical research, that take place in the mind affected by traumatic encounters. Central to my analysis are Shklovsky’s memoir A Sentimental Journey and his early articles on the theory of prose “Art as Device” and “The Relationship between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style” and Daniil Karms’s theoretical writings on the concepts of “nothingness,” “circle,” and “zero,” and his prose work written in the 1930s. -

My Birthplace

My birthplace Ягодарова Ангелина Николаевна My birthplace My birthplace Mari El The flag • We live in Mari El. Mari people belong to Finno- Ugric group which includes Hungarian, Estonians, Finns, Hanty, Mansi, Mordva, Komis (Zyrians) ,Karelians ,Komi-Permians ,Maris (Cheremises), Mordvinians (Erzas and Mokshas), Udmurts (Votiaks) ,Vepsians ,Mansis (Voguls) ,Saamis (Lapps), Khanti. Mari people speak a language of the Finno-Ugric family and live mainly in Mari El, Russia, in the middle Volga River valley. • http://aboutmari.com/wiki/Этнографические_группы • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b9NpQZZGuPI&feature=r elated • The rich history of Mari land has united people of different nationalities and religions. At this moment more than 50 ethnicities are represented in Mari El republic, including, except the most numerous Russians and Мari,Tatarians,Chuvashes, Udmurts, Mordva Ukranians and many others. Compare numbers • Finnish : Mari • 1-yksi ikte • 2-kaksi koktit • 3- kolme kumit • 4 -neljä nilit • 5 -viisi vizit • 6 -kuusi kudit • 7-seitsemän shimit • 8- kahdeksan kandashe • the Mari language and culture are taught. Lake Sea Eye The colour of the water is emerald due to the water plants • We live in Mari El. Mari people belong to Finno-Ugric group which includes Hungarian, Estonians, Finns, Hanty, Mansi, Mordva. • We have our language. We speak it, study at school, sing our tuneful songs and listen to them on the radio . Mari people are very poetic. Tourism Mari El is one of the more ecologically pure areas of the European part of Russia with numerous lakes, rivers, and forests. As a result, it is a popular destination for tourists looking to enjoy nature. -

Udmurtia. Horizons of Cooperation.Pdf

UDMURTIA Horizons of Cooperation The whole world is familiar fiber, 8th – in production of pork; or hammer out a nail for a house with the gun maker Mikhail Ka- it is among 5 major regions - fur- with your own hands to have a tra- lashnikov, motor cycles «Izh», the niture producers in Russia and ditional Udmurt wedding, to re- composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky and among 10 major regions of Russia cover physical health with help of the skier Galina Kulakova but as producing dairy and meat prod- unique mud, mineral waters and long as 20 years ago there were ucts. health-giving honey (apiotherapy) few people who were able to as- Acquaintance with future part- and spiritual health – in cathe- sociate them with Udmurtia. Now ners from Udmurtia is related to drals and at sacred springs, to re- it is just a fact in history explained business tourism. Citizens of oth- lieve stresses of the metropolitan by strategic significance of the er countries and regions of Russia city in the patriarchal tranquility Republic in the defense complex when selecting a holiday destina- of villages, to choose an educa- of Russia and its remoteness from tion will not consider our region tional institution for studying. the state borders. as a health resort or touristic cen- Udmurtia is the region of hospi- Business partner highly appre- ter along with London or Paris in table and purposeful people open ciate products manufactured in the first place. for dialogue and cooperation. the Republic and extend relations However, Udmurtia is attrac- with its manufacturers. tive not only as the industrial-in- Udmurtia produces equipment novative or educational center. -

Amur Oblast TYNDINSKY 361,900 Sq

AMUR 196 Ⅲ THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST SAKHA Map 5.1 Ust-Nyukzha Amur Oblast TY NDINS KY 361,900 sq. km Lopcha Lapri Ust-Urkima Baikal-Amur Mainline Tynda CHITA !. ZEISKY Kirovsky Kirovsky Zeiskoe Zolotaya Gora Reservoir Takhtamygda Solovyovsk Urkan Urusha !Skovorodino KHABAROVSK Erofei Pavlovich Never SKOVO MAGDAGACHINSKY Tra ns-Siberian Railroad DIRO Taldan Mokhe NSKY Zeya .! Ignashino Ivanovka Dzhalinda Ovsyanka ! Pioner Magdagachi Beketovo Yasny Tolbuzino Yubileiny Tokur Ekimchan Tygda Inzhan Oktyabrskiy Lukachek Zlatoustovsk Koboldo Ushumun Stoiba Ivanovskoe Chernyaevo Sivaki Ogodzha Ust-Tygda Selemdzhinsk Kuznetsovo Byssa Fevralsk KY Kukhterin-Lug NS Mukhino Tu Novorossiika Norsk M DHI Chagoyan Maisky SELE Novovoskresenovka SKY N OV ! Shimanovsk Uglovoe MAZ SHIMA ANOV Novogeorgievka Y Novokievsky Uval SK EN SK Mazanovo Y SVOBODN Chernigovka !. Svobodny Margaritovka e CHINA Kostyukovka inlin SERYSHEVSKY ! Seryshevo Belogorsk ROMNENSKY rMa Bolshaya Sazanka !. Shiroky Log - Amu BELOGORSKY Pridorozhnoe BLAGOVESHCHENSKY Romny Baikal Pozdeevka Berezovka Novotroitskoe IVANOVSKY Ekaterinoslavka Y Cheugda Ivanovka Talakan BRSKY SKY P! O KTYA INSK EI BLAGOVESHCHENSK Tambovka ZavitinskIT BUR ! Bakhirevo ZAV T A M B OVSKY Muravyovka Raichikhinsk ! ! VKONSTANTINO SKY Poyarkovo Progress ARKHARINSKY Konstantinovka Arkhara ! Gribovka M LIKHAI O VSKY ¯ Kundur Innokentevka Leninskoe km A m Trans -Siberianad Railro u 100 r R i v JAO Russian Far East e r By Newell and Zhou / Sources: Ministry of Natural Resources, 2002; ESRI, 2002. Newell, J. 2004. The Russian Far East: A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development. McKinleyville, CA: Daniel & Daniel. 466 pages CHAPTER 5 Amur Oblast Location Amur Oblast, in the upper and middle Amur River basin, is 8,000 km east of Moscow by rail (or 6,500 km by air). -

Russian Army, 4 June 1916

Russian Army 4 June 1916 Northwest Front: Finland Garrison: XLII Corps: 106th Infantry Division 421st Tsarskoe Selo Infantry Regiment 422nd Kolpino Infantry Regiment 423rd Luga Infantry Regiment 424th Chut Infantry Regiment 107th Infantry Division 425th Kargopol Infantry Regiment 426th Posinets Infantry Regiment 427th Pudozh Infantry Regiment 428th Lodeyinpol Infantry Regiment Sveaborg Border Brigade 1st Sveaborg Border Regiment 2nd Sveaborg Border Regiment Estonia Coast Defense: 108th Infantry Division 429th Riizhsk Infantry Regiment 430th Balksy Infantry Regiment 431st Tikhvin Infantry Regiment 432nd Baldaia Infantry Regiment Revel Border Brigade 1st Revel Border Regiments 2nd Revel Border Regiments Livonia Coast Defense: I Corps 22nd Novgorod Infantry Division 85th Vyborg Infantry Regiment 86th Wilmanstrand Infantry Regiment 87th Neschlot Infantry Regiment 88th Petrov Infantry Regiment 24th Pskov Infantry Division 93rd Irkhtsk Infantry Regiment 94th Yenisei Infantry Regiment 95th Krasnoyarsk Infantry Regiment 96th Omsk Infantry Regiment III Corps 73rd Orel Infantry Division 289th Korotoyav Infantry Regiment 290th Valuiisk Infantry Regiment 291st Trubchev Infantry Regiment 292nd New Archangel Infantry Regiment 5th Rifle Division (Suwalki) 17th Rifle Regiment 18th Rifle Regiment 19th Rifle Regiment 20th Rifle Regiment V Siberian Corps 1 50th St. Petersburg Infantry Division 197th Lesnot Infantry Regiment 198th Alexander Nevsky Infantry Regiment 199th Kronstadt Infantry Regiment 200th Kronshlot Infantry Regiment 6th (Khabarovsk) Siberian -

State Building in Revolutionary Ukraine

STATE BUILDING IN REVOLUTIONARY UKRAINE Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM This page intentionally left blank Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM STEPHEN VELYCHENKO STATE BUILDING IN REVOLUTIONARY UKRAINE A Comparative Study of Governments and Bureaucrats, 1917–1922 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2011 Toronto Buffalo London www.utppublishing.com Printed in Canada ISBN 978-1-4426-4132-7 Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable- based inks. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Velychenko, Stephen State building in revolutionary Ukraine: a comparative study of governments and bureaucrats, 1917–1922/Stephen Velychenko. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4426-4132-7 1. Ukraine – Politics and government – 1917–1945. 2. Public adminstration – Ukraine – History – 20th century. 3. Nation-building – Ukraine – History – 20th century 4. Comparative government. I. Title DK508.832.V442011 320.9477'09041 C2010-907040-2 The research for this book was made possible by University of Toronto Humanities and Social Sciences Research Grants, by the Katedra Foundation, and the John Yaremko Teaching Fellowship. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Programme, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the fi nancial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the fi nancial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for its publishing activities. -

Introduction 11. I Have Approached This Subject in Greater Detail in J. D

NOTES Introduction 11. I have approached this subject in greater detail in J. D. White, Karl Marx and the Intellectual Origins of Dialectical Materialism (Basingstoke and London, 1996). 12. V. I. Lenin, Collected Works, Vol. 38, p. 180. 13. K. Marx, Grundrisse, translated by M. Nicolaus (Harmondsworth, 1973), p. 408. 14. N. I. Ziber, Teoriia tsennosti i kapitala D. Rikardo v sviazi s pozdneishimi dopolneniiami i raz"iasneniiami. Opyt kritiko-ekonomicheskogo issledovaniia (Kiev, 1871). 15. N. G. Chernyshevskii, ‘Dopolnenie i primechaniia na pervuiu knigu politicheskoi ekonomii Dzhon Stiuarta Millia’, Sochineniia N. Chernyshevskogo, Vol. 3 (Geneva, 1869); ‘Ocherki iz politicheskoi ekonomii (po Milliu)’, Sochineniia N. Chernyshevskogo, Vol. 4 (Geneva, 1870). Reprinted in N. G. Chernyshevskii, Polnoe sobranie sochineniy, Vol. IX (Moscow, 1949). 16. Arkhiv K. Marksa i F. Engel'sa, Vols XI–XVI. 17. M. M. Kovalevskii, Obshchinnoe zemlevladenie, prichiny, khod i posledstviia ego razlozheniia (Moscow, 1879). 18. Marx to the editorial board of Otechestvennye zapiski, November 1877, in Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Vol. 24, pp. 196–201. 19. Marx to Zasulich, 8 March 1881, in Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Vol. 24, pp. 346–73. 10. It was published in the journal Vestnik Narodnoi Voli, no. 5 (1886). 11. D. Riazanov, ‘V Zasulich i K. Marks’, Arkhiv K. Marksa i F. Engel'sa, Vol. 1 (1924), pp. 269–86. 12. N. F. Daniel'son, ‘Ocherki nashego poreformennogo obshch- estvennogo khoziaistva’, Slovo, no. 10 (October 1880), pp. 77–143. 13. N. F. Daniel'son, Ocherki nashego poreformennogo obshchestvennogo khozi- aistva (St Petersburg, 1893). 14. V. V. Vorontsov, Sud'by kapitalizma v Rossii (St Petersburg, 1882).