Archiving Memories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sujin Huggins.Pdf

HOW DID WE GET HERE?: AN EXAMINATION OF THE COLLECTION OF CONTEMPORARY CARIBBEAN JUVENILE LITERATURE IN THE CHILDREN’S LIBRARY OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF TRINIDAD & TOBAGO AND TRINIDADIAN CHILDREN’S RESPONSES TO SELECTED TITLES BY SUJIN HUGGINS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Library and Information Science in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christine Jenkins, Chair and Director of Research Professor Violet Harris Professor Linda Smith Assistant Lecturer Louis Regis, University of the West Indies, St. Augustine ABSTRACT This study investigates the West Indian Juvenile collection of Caribbean children's literature housed at the Port of Spain Children's Library of the National Library of Trinidad and Tobago to determine its characteristics and contents, and to elicit the responses of a group of children, aged 11 to 13, to selected works from the collection. A variety of qualitative data collection techniques were employed including document analysis, direct observation, interviews with staff, and focus group discussions with student participants. Through collection analysis, ethnographic content analysis and interview analysis, patterns in the literature and the responses received were extracted in an effort to construct and offer a 'holistic' view of the state of the literature and its influence, and suggest clear implications for its future development and use with children in and out of libraries throughout the region. ii For my grandmother Earline DuFour-Herbert (1917-2007), my eternal inspiration, and my daughter, Jasmine, my constant motivation. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To adequately thank all of the wonderful people who have made the successful completion of this dissertation possible would require another dissertation-length document. -

Caribbean Voices Broadcasts

APPENDIX © The Author(s) 2016 171 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE BBC CARIBBEAN VOICES BROADCASTS March 11th 1943 to September 7th 1958 © The Author(s) 2016 173 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE BBC CARIBBEAN VOICES EDITORS Una Marson April 1940 to December 1945 Mary Treadgold December 1945 to July 1946 Henry Swanzy July 1946 to November 1954 Vidia Naipaul December 1954 to September 1956 Edgar Mittelholzer October 1956 to September 1958 © The Author(s) 2016 175 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE WEST INDIES FEDERATION AND THE TERRITORIES INCLUDED January 3 1958 to 31 May 31 1962 Antigua & Barbuda Barbados Dominica Grenada Jamaica Montserrat St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla St. Lucia St. Vincent and the Grenadines Trinidad and Tobago © The Author(s) 2016 177 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 CARIBBEAN VOICES : INDEX OF AUTHORS AND SEQUENCE OF BROADCASTS Author Title Broadcast sequence Aarons, A.L.C. The Cow That Laughed 1369 The Dancer 43 Hurricane 14 Madam 67 Mrs. Arroway’s Joe 1 Policeman Tying His Laces 156 Rain 364 Santander Avenue 245 Ablack, Kenneth The Last Two Months 1029 Adams, Clem The Seeker 320 Adams, Robert Harold Arundel Moody 111 Albert, Nelly My World 496 Alleyne, Albert The Last Mule 1089 The Rock Blaster 1275 The Sign of God 1025 Alleyne, Cynthia Travelogue 1329 Allfrey, Phyllis Shand Andersen’s Mermaid 1134 Anderson, Vernon F. -

The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Poetry Edited by Jahan Ramazani Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09071-2 — The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Poetry Edited by Jahan Ramazani Frontmatter More Information the cambridge companion to postcolonial poetry The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Poetry is the first collection of essays to explore postcolonial poetry through regional, historical, political, formal, textual, gender, and comparative approaches. The essays encompass a broad range of English-speakers from the Caribbean, Africa, South Asia, and the Pacific Islands; the former settler colonies, such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, especially non-Europeans; Ireland, Britain’s oldest colony; and post- colonial Britain itself, particularly black and Asian immigrants and their descen- dants. The comparative essays analyze poetry from across the postcolonial anglophone world in relation to postcolonialism and modernism, fixed and free forms, experimentation, oral performance and creole languages, protest poetry, the poetic mapping of urban and rural spaces, poetic embodiments of sexuality and gender, poetry and publishing history, and poetry’s response to, and reimagining of, globalization. Strengthening the place of poetry in postco- lonial studies, this Companion also contributes to the globalization of poetry studies. jahan ramazani is University Professor and Edgar F. Shannon Professor of English at the University of Virginia. He is the author of five books: Poetry and its Others: News, Prayer, Song, and the Dialogue of Genres (2013); A Transnational Poetics (2009), winner of the 2011 Harry Levin Prize of the American Comparative Literature Association, awarded for the best book in comparative literary history published in the years 2008 to 2010; The Hybrid Muse: Postcolonial Poetry in English (2001); Poetry of Mourning: The Modern Elegy from Hardy to Heaney (1994), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award; and Yeats and the Poetry of Death: Elegy, Self-Elegy, and the Sublime (1990). -

Vol 25 / No. 2 / November 2017 Volume 24 Number 2 November 2017

1 Vol 25 / No. 2 / November 2017 Volume 24 Number 2 November 2017 Published by the discipline of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Self-portrait with projection, October 2017, img_9723 by Rodell Warner Anu Lakhan (copy editor) Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] OR Ms. Angela Trotman Department of Language, Linguistics and Literature Faculty of Humanities, UWI Cave Hill Campus P.O. Box 64, Bridgetown, BARBADOS, W.I. e-mail: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTION RATE US$20 per annum (two issues) or US$10 per issue Copyright © 2017 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Lisa Outar Ian Strachan BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. Edited by full time academics and with minimal funding or institutional support, the Journal originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. -

Brave New World Service a Unique Opportunity for the Bbc to Bring the World to the UK

BRAVE NEW WORLD SERVIce A UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY FOR THE BBC TO BRING THE WORLD TO THE UK JOHN MCCaRTHY WITH CHARLOTTE JENNER CONTENTS Introduction 2 Value 4 Integration: A Brave New World Service? 8 Conclusion 16 Recommendations 16 INTERVIEWEES Steven Barnett, Professor of Communications, Ishbel Matheson, Director of Media, Save the Children and University of Westminster former East Africa Correspondent, BBC World Service John Baron MP, Member of Foreign Affairs Select Committee Rod McKenzie, Editor, BBC Radio 1 Newsbeat and Charlie Beckett, Director, POLIS BBC 1Xtra News Tom Burke, Director of Global Youth Work, Y Care International Richard Ottaway MP, Chair, Foreign Affairs Select Committee Alistair Burnett, Editor, BBC World Tonight Rita Payne, Chair, Commonwealth Journalists Mary Dejevsky, Columnist and leader writer, The Independent Association and former Asia Editor, BBC World and former newsroom subeditor, BBC World Service Marcia Poole, Director of Communications, International Jim Egan, Head of Strategy and Distribution, BBC Global News Labour Organisation (ILO) and former Head of the Phil Harding, Journalist and media consultant and former World Service training department Director of English Networks and News, BBC World Service Stewart Purvis, Professor of Journalism and former Lindsey Hilsum, International Editor, Channel 4 News Chief Executive, ITN Isabel Hilton, Editor of China Dialogue, journalist and broadcaster Tony Quinn, Head of Planning, JWT Mary Hockaday, Head of BBC Newsroom Nick Roseveare, Chief Executive, BOND Peter -

071209 Bush Writers Portfolio FINAL SW

Bush Writers 1940 - 2012 A Witness Seminar Bush House 9th December 2009 Bush Writers Witness Seminar 9th December 2009 Contents Aims Page 3 Timetable Page 4 Seminar questions Page 5 ‘Bush Writers’ project outline Page 6 ‘Bush Writers’ website and publication plans Page 7 Bush Writers and extracts for 9/12/09 seminar Page 8 Bush Writers and extracts from seminar two Page 31 Bush Writers and extracts from seminar three Page 46 Cover Image: Voice - the monthly radio magazine programme which broadcasts modern poetry to English-speaking India in the Eastern Service of the BBC. l-r, sitting Venu Chitale, a member of the BBC Indian Section, M.J.Tambimuttu, a Tamil from Ceylon, editor of Poetry (London) T.S. Eliot ; Una Marson, BBC West Indian Programme Organiser, Mulk Raj Anand, Indian novelist, Christopher Pemberton, a member of the BBC staff, Narayana Menon, Indian writer. l-r, standing George Orwell, author and producer of the programme, Nancy Parratt, secretary to George Orwell, William Empson, poet and critic 2 Bush Writers Seminar 9th December 2009 Dear Friends and Colleagues, The purpose of this three-part seminar series is to bring together Bush Writers (former and current, published and aspiring) in order to share their experiences of and memories as “secret agents” of literature at Bush House. This seminar series is part of a larger research project and a unique partnership between The Open University and the BBC World Service.1 It examines diasporic cultures at Bush House from 1940 to 2012 when the Bush House era will end as staff move out and take up new working premises (see project outline pg. -

Island Ecologies and Caribbean Literatures1

ISLAND ECOLOGIES AND CARIBBEAN LITERATURES1 ELIZABETH DELOUGHREY Department of English, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 2003 ABSTRACT This paper examines the ways in which European colonialism positioned tropical island landscapes outside the trajectories of modernity and history by segregating nature from culture, and it explores how contemporary Caribbean authors have complicated this opposition. By tracing the ways in which island colonisation transplanted and hybridised both peoples and plants, I demonstrate how mainstream scholarship in disciplines as diverse as biogeography, anthropology, history, and literature have neglected to engage with the deep history of island landscapes. I draw upon the literary works of Caribbean writers such as Édouard Glissant, Wilson Harris, Jamaica Kincaid and Olive Senior to explore the relationship between landscape and power. Key words: Islands, literature, Caribbean, ecology, colonialism, environment THE LANGUAGE OF LANDSCAPE the relationship between colonisation and ecology is rendered most visible in island spaces. Perhaps there is no other region in the world This has much to do with the ways in which that has been more radically altered in terms European colonialism travelled from one island of flora and fauna than the Caribbean islands. group to the next. Tracing this movement across Although Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles the Atlantic from the Canaries and Azores to Darwin had been the first to suggest that islands the Caribbean, we see that these archipelagoes are particularly susceptible to biotic arrivants, became the first spaces of colonial experimen- and David Quammen’s more recent The Song tation in terms of sugar production, deforestation, of the Dodo has popularised island ecology, other the importation of indentured and enslaved scholars have made more significant connec- labour, and the establishment of the plantoc- tions between European colonisation and racy system. -

Una Marson Podcast

Una Marson - Transcript When World War 2 broke out in 1939, thousands of men and women from across the West Indies were joining up to fight for the Allied cause, whilst others signed up for factory work. Many would be stationed in Britain, nearly four thousand miles from home. The BBC realising that serving men and women would want to send messages to loved ones, launched the programme Call the West Indies, which mixed personal messages, music and inspirational stories of war work. The young woman, who produced and presented the show was a true pioneer, the first black producer on the BBC’s payroll and once described as “the most significant black British feminist of the interwar years.” But her life and work have often been overlooked, so today we remember Una Marson: Una was born near Santa Cruz in rural Jamaica on 6 February 1905 to Reverend Solomon Isaac and Ada Marson. She was the youngest of nine children, three of whom her parents had adopted and the family was relatively prosperous for the time. Her father was a strict baptist preacher and even as a young child, Una was rebellious, fighting against the restrictions imposed upon on her by culture and tradition. But she was extremely bright and her sisters introduced her to poetry which she would describe as “the chief delight of our childhood days”. Una had been born into a British colonial world and was heavily exposed to English classical literature. Early on she felt instinctively opposed to the idea perpetuated at the time that in some way her own race was inferior. -

Gender, Ethnicity and Literary Represenation

• 96 • Feminist Africa 7 Fashioning women for a brave new world: gender, ethnicity and literary representation Paula Morgan This essay adds to the ongoing dialogue on the literary representation of Caribbean women. It grapples with a range of issues: how has iconic literary representation of the Caribbean woman altered from the inception of Caribbean women’s writing to the present? Given that literary representation was a tool for inscribing otherness and a counter-discursive device for recuperating the self from the imprisoning gaze, how do the politics of identity, ethnicity and representation play out over time? How does representation shift when one considers the gender and ethnicity of the protagonist in relation to that of the writer? Can we assume that self-representation is necessarily the most “authentic”? And how has the configuration of the representative West Indian writer changed since the 1970s to the present? The problematics of literary representation have been with us since Plato and Aristotle wrestled with the purpose of fiction and the role of the artist in the ideal republic. Its problematics were foregrounded in feminist dialogues on the power of the male gaze to objectify and subordinate women. These problematics were also central to so-called third-world and post-colonial critics concerned with the correlation between imperialism and the projection/ internalisation of the gaze which represented the subaltern as sub-human. Representation has always been a pivotal issue in female-authored Caribbean literature, with its nagging preoccupation with identity formation, which must be read through myriad shifting filters of gender and ethnicity. Under any circumstance, representation remains a vexing theoretical issue. -

Autumn 2003 JSSE Twentieth Anniversary

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 41 | Autumn 2003 JSSE twentieth anniversary Olive Senior - b. 1941 Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/337 ISSN: 1969-6108 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2003 Number of pages: 287-298 ISSN: 0294-04442 Electronic reference Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize, « Olive Senior - b. 1941 », Journal of the Short Story in English [Online], 41 | Autumn 2003, Online since 31 July 2008, connection on 03 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/jsse/337 This text was automatically generated on 3 December 2020. © All rights reserved Olive Senior - b. 1941 1 Olive Senior - b. 1941 Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize EDITOR'S NOTE Interviewed by Dominique Dubois, and Jeanne Devoize., Caribbean Short Story Conference, January 19, 1996.First published in JSSE n°26, 1996. Dominique DUBOIS: Would you regard yourself as a feminist writer? Olive SENIOR: When I started to write, I wasn't conscious about feminism and those issues. I think basically my writing reflects my society and how it functions. Obviously, one of my concerns is gender. I tend to avoid labels. Jeanne DEVOIZE: How can you explain that there are so many women writers in Jamaica, particularly as far as the short story is concerned. O.S.: I think there are a number of reasons. One is that it reflects what happened historically in terms of education: that a lot more women were, at a particular point in time, being educated through high school, through university and so on. -

Jamaican Women Poets and Writers' Approaches to Spirituality and God By

RE-CONNECTING THE SPIRIT: Jamaican Women Poets and Writers' Approaches to Spirituality and God by SARAH ELIZABETH MARY COOPER A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre of West African Studies School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham October 2004 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Chapter One asks whether Christianity and religion have been re-defined in the Jamaican context. The definitions of spirituality and mysticism, particularly as defined by Lartey are given and reasons for using these definitions. Chapter Two examines history and the Caribbean religious experience. It analyses theory and reflects on the Caribbean difference. The role that literary forefathers and foremothers have played in defining the writers about whom my research is concerned is examined in Chapter Three, as are some of their selected works. Chapter Four reflects on the work of Lorna Goodison, asks how she has defined God whether within a Christian or African framework. In contrast Olive Senior appears to view Christianity as oppressive and this is examined in Chapter Five. -

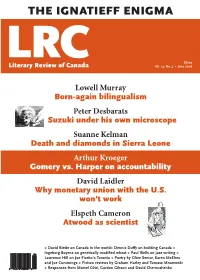

The Ignatieff Enigma

THE IGNATIEFF ENIGMA $6.00 LRCLiterary Review of Canada Vol. 14, No. 5 • June 2006 Lowell Murray Born-again bilingualism Peter Desbarats Suzuki under his own microscope Suanne Kelman Death and diamonds in Sierra Leone Arthur Kroeger Gomery vs. Harper on accountability David Laidler Why monetary union with the U.S. won’t work Elspeth Cameron Atwood as scientist + David Biette on Canada in the world+ Dennis Duffy on building Canada + Ingeborg Boyens on genetically modified wheat + Paul Wells on jazz writing + Lawrence Hill on Joe Fiorito’s Toronto + Poetry by Olive Senior, Karen McElrea and Joe Cummings + Fiction reviews by Graham Harley and Tomasz Mrozewski + Responses from Marcel Côté, Gordon Gibson and David Chernushenko ADDRESS Literary Review of Canada 581 Markham Street, Suite 3A Toronto, Ontario m6g 2l7 e-mail: [email protected] LRCLiterary Review of Canada reviewcanada.ca T: 416 531-1483 Vol. 14, No. 5 • June 2006 F: 416 531-1612 EDITOR Bronwyn Drainie 3 Beyond Shame and Outrage 18 Astronomical Talent [email protected] An essay A review of Fabrizio’s Return, by Mark Frutkin ASSISTANT EDITOR Timothy Brennan Graham Harley Alastair Cheng 6 Death and Diamonds 19 A Dystopic Debut CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Anthony Westell A review of A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and A review of Zed, by Elizabeth McClung the Destruction of Sierra Leone, by Lansana Gberie Tomasz Mrozewski ASSOCIATE EDITOR Robin Roger Suanne Kelman 20 Scientist, Activist or TV Star? POETRY EDITOR 8 Making Connections A review of David Suzuki: The Autobiography Molly