Island Ecologies and Caribbean Literatures1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender, Ethnicity and Literary Represenation

• 96 • Feminist Africa 7 Fashioning women for a brave new world: gender, ethnicity and literary representation Paula Morgan This essay adds to the ongoing dialogue on the literary representation of Caribbean women. It grapples with a range of issues: how has iconic literary representation of the Caribbean woman altered from the inception of Caribbean women’s writing to the present? Given that literary representation was a tool for inscribing otherness and a counter-discursive device for recuperating the self from the imprisoning gaze, how do the politics of identity, ethnicity and representation play out over time? How does representation shift when one considers the gender and ethnicity of the protagonist in relation to that of the writer? Can we assume that self-representation is necessarily the most “authentic”? And how has the configuration of the representative West Indian writer changed since the 1970s to the present? The problematics of literary representation have been with us since Plato and Aristotle wrestled with the purpose of fiction and the role of the artist in the ideal republic. Its problematics were foregrounded in feminist dialogues on the power of the male gaze to objectify and subordinate women. These problematics were also central to so-called third-world and post-colonial critics concerned with the correlation between imperialism and the projection/ internalisation of the gaze which represented the subaltern as sub-human. Representation has always been a pivotal issue in female-authored Caribbean literature, with its nagging preoccupation with identity formation, which must be read through myriad shifting filters of gender and ethnicity. Under any circumstance, representation remains a vexing theoretical issue. -

Autumn 2003 JSSE Twentieth Anniversary

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 41 | Autumn 2003 JSSE twentieth anniversary Olive Senior - b. 1941 Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/337 ISSN: 1969-6108 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2003 Number of pages: 287-298 ISSN: 0294-04442 Electronic reference Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize, « Olive Senior - b. 1941 », Journal of the Short Story in English [Online], 41 | Autumn 2003, Online since 31 July 2008, connection on 03 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/jsse/337 This text was automatically generated on 3 December 2020. © All rights reserved Olive Senior - b. 1941 1 Olive Senior - b. 1941 Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize EDITOR'S NOTE Interviewed by Dominique Dubois, and Jeanne Devoize., Caribbean Short Story Conference, January 19, 1996.First published in JSSE n°26, 1996. Dominique DUBOIS: Would you regard yourself as a feminist writer? Olive SENIOR: When I started to write, I wasn't conscious about feminism and those issues. I think basically my writing reflects my society and how it functions. Obviously, one of my concerns is gender. I tend to avoid labels. Jeanne DEVOIZE: How can you explain that there are so many women writers in Jamaica, particularly as far as the short story is concerned. O.S.: I think there are a number of reasons. One is that it reflects what happened historically in terms of education: that a lot more women were, at a particular point in time, being educated through high school, through university and so on. -

Jamaican Women Poets and Writers' Approaches to Spirituality and God By

RE-CONNECTING THE SPIRIT: Jamaican Women Poets and Writers' Approaches to Spirituality and God by SARAH ELIZABETH MARY COOPER A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre of West African Studies School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham October 2004 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Chapter One asks whether Christianity and religion have been re-defined in the Jamaican context. The definitions of spirituality and mysticism, particularly as defined by Lartey are given and reasons for using these definitions. Chapter Two examines history and the Caribbean religious experience. It analyses theory and reflects on the Caribbean difference. The role that literary forefathers and foremothers have played in defining the writers about whom my research is concerned is examined in Chapter Three, as are some of their selected works. Chapter Four reflects on the work of Lorna Goodison, asks how she has defined God whether within a Christian or African framework. In contrast Olive Senior appears to view Christianity as oppressive and this is examined in Chapter Five. -

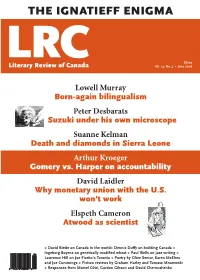

The Ignatieff Enigma

THE IGNATIEFF ENIGMA $6.00 LRCLiterary Review of Canada Vol. 14, No. 5 • June 2006 Lowell Murray Born-again bilingualism Peter Desbarats Suzuki under his own microscope Suanne Kelman Death and diamonds in Sierra Leone Arthur Kroeger Gomery vs. Harper on accountability David Laidler Why monetary union with the U.S. won’t work Elspeth Cameron Atwood as scientist + David Biette on Canada in the world+ Dennis Duffy on building Canada + Ingeborg Boyens on genetically modified wheat + Paul Wells on jazz writing + Lawrence Hill on Joe Fiorito’s Toronto + Poetry by Olive Senior, Karen McElrea and Joe Cummings + Fiction reviews by Graham Harley and Tomasz Mrozewski + Responses from Marcel Côté, Gordon Gibson and David Chernushenko ADDRESS Literary Review of Canada 581 Markham Street, Suite 3A Toronto, Ontario m6g 2l7 e-mail: [email protected] LRCLiterary Review of Canada reviewcanada.ca T: 416 531-1483 Vol. 14, No. 5 • June 2006 F: 416 531-1612 EDITOR Bronwyn Drainie 3 Beyond Shame and Outrage 18 Astronomical Talent [email protected] An essay A review of Fabrizio’s Return, by Mark Frutkin ASSISTANT EDITOR Timothy Brennan Graham Harley Alastair Cheng 6 Death and Diamonds 19 A Dystopic Debut CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Anthony Westell A review of A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and A review of Zed, by Elizabeth McClung the Destruction of Sierra Leone, by Lansana Gberie Tomasz Mrozewski ASSOCIATE EDITOR Robin Roger Suanne Kelman 20 Scientist, Activist or TV Star? POETRY EDITOR 8 Making Connections A review of David Suzuki: The Autobiography Molly -

The Engagement Between Past and Present in African American And

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy The Engagement between Past and Present in African American and Caribbean Literature: Orality in the Fiction of Toni Morrison, Gayl Jones, Edwidge Danticat, and Olive Senior by Jacoba Bruneel Paper submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- Prof. Ilka Saal en Letterkunde: Engels” May, 2010 The Engagement between Past and Present in African American and Caribbean Literature: Orality in the Fiction of Toni Morrison, Gayl Jones, Edwidge Danticat, and Olive Senior by Jacoba Bruneel Prof. Ilka Saal Ghent University Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Ilka Saal, for her advice and guidance which helped me to gain new insights into my topic, and for her enthusiasm which encouraged me to delve deeper. Special thanks to Dr. James Procter of the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, whose fascinating lectures on the Caribbean short story sparked my interest in the literature of the Caribbean, and to Prof. Susan Griffin who stimulated my interest in scholarly research in her “Scenes of Reading” seminars. I would also like to thank my family for their warm support and encouragements, and my friends for standing by me during these stressful times and for being there when I most needed them. Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 1. Similarities in the Use of Orality in African American and Caribbean Fiction ............. 10 1.1. Vernacular in Dialogue and Narrative .................................................................... 11 1.2. Written Performance ............................................................................................... 16 1.3. Call-and-Response: Seeking Engagement .............................................................. 20 1.4. Orality and the Written Text: a Fertile Hybridity .................................................. -

Book Reviews -Gesa Mackenthun, Stephen Greenblatt, Marvelous Possessions: the Wonder of the New World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991

Book Reviews -Gesa Mackenthun, Stephen Greenblatt, Marvelous Possessions: The wonder of the New World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991. ix + 202 pp. -Peter Redfield, Peter Hulme ,Wild majesty: Encounters with Caribs from Columbus to the present day. An Anthology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. x + 369 pp., Neil L. Whitehead (eds) -Michel R. Doortmont, Philip D. Curtin, The rise and fall of the plantation complex: Essays in Atlantic history. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990. xi + 222 pp. -Roderick A. McDonald, Hilary McD.Beckles, A history of Barbados: From Amerindian settlement to nation-state. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. xv + 224 pp. -Gertrude J. Fraser, Hilary McD.Beckles, Natural rebels; A social history of enslaved black women in Barbados. New Brunswick NJ and London: Rutgers University Press and Zed Books, 1990 and 1989. ix + 197 pp. -Bridget Brereton, Thomas C. Holt, The problem of freedom: Race, labor, and politics in Jamaica and Britain, 1832-1938. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1991. xxxi + 517 pp. -Peter C. Emmer, A. Meredith John, The plantation slaves of Trinidad, 1783-1816: A mathematical and demographic inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. xvi + 259 pp. -Richard Price, Robert Cohen, Jews in another environment: Surinam in the second half of the eighteenth century. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1991. xv + 350 pp. -Russell R. Menard, Nigel Tattersfield, The forgotten trade: comprising the log of the Daniel and Henry of 1700 and accounts of the slave trade from the minor ports of England, 1698-1725. London: Jonathan Cape, 1991. ixx + 460 pp. -John D. Garrigus, James E. -

Unstable Identities: Michelle Cliff and Olive Senior “Shortstorytelling” Jamaica

FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍA INGLESA TESIS DOCTORAL UNSTABLE IDENTITIES: MICHELLE CLIFF AND OLIVE SENIOR “SHORTSTORYTELLING” JAMAICA EVA MARÍA MÉNDEZ BLÁZQUEZ DIRIGIDA POR: DRA. JULIA SALMERÓN CABAÑAS Conclusión La primera vez que leí las historias cortas de Olive Senior and Michelle Cliff fue durante mi beca Erasmus en Louvain-la–Neuve, Bélgica. Formaban parte de la lectura obligatoria de una asignatura llamada Modernism/Postmodernism. Todo era nuevo para mí y me enamoré de sus historias ya que eran muy diferentes de todo aquello que había leído con anterioridad. En seguida, me transportaron a un mundo exótico en una remota isla caribeña de la que solo había oído a través de agencias turísticas como un lugar donde descansar y comer sin límite en hoteles de todo incluido. Ambas autoras me mostraron un paraíso muy diferente en el cual la gente luchaba por su derecho a ser independientes y donde las mujeres trataban de evitar el estigma que el postcolonialismo y el patriarcado les había impuesto. Mi viaje a través de su literature fue también muy diferente; me sentí una parte de la isla, empaticé con sus protagonistas y sus preocupaciones raciales y con respecto a las tradiciones de la isla. En su ensayo “Hacia un criticismo feminista negro” (“Towards a Black Feminist Criticism”), Barbara Smith (1986) explica como las cuestiones raciales y de género han sido consideradas de forma separada. Ella reclama que ni los hombres negros ni las mujeres feministas blancas comprenden la doble presión impuesta sobre las mujeres negras. Por tanto, hablar de cuestiones sociales y de género conjuntamente siendo una mujer blanca occidental debería ser imposible ya que no se puede sentir esa doble presión que sienten las mujeres negras. -

Archiving Memories

Orality in the Body of the Archive: Memorialising Representations of Creole Language and Culture in the Technologised Word A thesis submitted by Marl’ene Edwin in the fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English and Comparative Literature, Goldsmiths, University of London, 2016 I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work. Marl’ene Edwin 2 Dedicated to the memory of my beloved mother and father Linnette (1933-1996) and George (1925-1998) 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Too many people to mention here, Who have helped me along the way. However, there are a few things I find I must say. Overwhelming thanks to Professor Joan Anim-Addo, Supervisor, mentor and critical friend Without your pushing and pulling, This project would never have made it to the end. My colleagues in CELAW you know who you are. Natasha and fellow students in the Centre for Caribbean and Diaspora Studies, This is not the end by far! To my upgrade examiners, Clea Bourne and Geri Popova, Much food for thought And time to work my thesis over. For her quick reading and mock exam I extend my warmest regards To Maria Helena Lima and Our network of women in Europe and afar. For conducting the final examination, Viv Golding and Pia Pichler, I’ve run out of words and my face Must have been a picture! To my friends and family who have been with me to the end, Special thanks to Karol and Deirdre, two very good friends, Brothers and Sisters how could I miss you out Estola, Jasper, Marcia, Sandra, Yvette and Dave, there is no doubt This thesis is for us all, whether from a big island or small!! Jo and Steve, what can I say, Our weekend jaunts certainly saved the day. -

The Strangers

Why do I write? Patricia Cumper Although I wrote my first play at 23, my writing life began years earlier. I always got good marks at school. I was clever and I came from a clever family, said my teachers. The truth was a little more complex. I have always read copiously: from the Bobbsey Twins and Nancy Drew stories of my childhood to holiday reading by Agatha Christie, Georgette Heyer and Ellis Peters. I read Jamaican writers like Erna Brodber, Jean D’Costa, Olive Senior and Lorna Goodison; I learnt something of the Jewish experience from Anne Frank and Leon Uris; about the wider Caribbean from Andrew Salkey, Kamau Brathwaite and Derek Walcott; the lives of Black Americans through the words of Alice Walker, Toni Cade Bambara and Toni Morrison. Indeed, when I eventually came to university in England, I wanted to be sure that I was not at a disadvantage so I set myself the task of reading the classics. I got as far as all of Shakespeare’s plays and most of his son- nets, the Brontë sisters’ books, and D. H. Lawrence’s short stories Love Among the Haystacks but sadly stalled a hundred or so pages into Crime and Punishment. I also grew up in a household where debate was the most popular occupation. Not arguing. I only ever heard my parents argue once in my whole childhood and it shook me to the core, it was that aberrant. We – my brother, sister and I – debated. Over dinner. In the back of the old family Volkswagen. -

Peter Abrahams. Mine Boy (Southern Africa – South Africa) Chinua Achebe

WORLD LITERATURE: EMPHASIS IN WORLD LITERATURE IN ENGLISH (POSTCOLONIAL) GRADUATE COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION READING LIST SELECTED BY THE GRADUATE FACULTY THE CANDIDATE IS RESPONSIBLE FOR AT LEAST TWENTY-ONE MAJOR WORKS OR AUTHORS FROM AT LEAST THREE GEOGRAPHICAL REGIONS, DISTRIBUTED AS FOLLOWS: FICTION FROM AMONG THE FOLLOWING, SELECT AT LEAST EIGHT NOVELS OR STORY COLLECTIONS FROM AT LEAST THREE DIFFERENT GEOGRAPHICAL REGIONS: Peter Abrahams. Mine Boy (Southern Africa – South Africa) Chinua Achebe. Things Fall Apart, A Man of the People or Anthills of the Savannah (West Africa - Nigeria) Ama Ata Aidoo. Our Sister Killjoy or No Sweetness Here (West Africa – Ghana) Monica Ali. Brick Lane (Pakistan/England) Mulk Raj Anand. The Village, Untouchable, or Coolie (India) Ayi Kwei Armah. The Beautyful Ones are Not Yet Born (West Africa – Ghana) Erna Brodber. Jane and Louisa Will Soon Come Home (West Indies – Jamaica) Peter Carey. Any Novel (Australia) Michelle Cliff. Abeng or No Telephone to Heaven (West Indies – Jamaica) J.M. Coetzee. Waiting for the Barbarians; Life and Times of Michael K., Age of Iron, or Disgrace (Southern Africa – South Africa) Merle Collins. Angel or The Colour of Forgetting (Grenada) Tsitsi Dangarembga. Nervous Conditions (Southern Africa – Zimbabwe) Edwidge Danticat. Breath Eyes Memory, Krik? Krak! or The Farming of Bones (West Indies – Haiti) Anita Desai. Clear Light of Day (India) Alan Duff. Once Were Warriors (New Zealand) Buchi Emecheta. The Joys of Motherhood (West Africa – Nigeria) Nuruddin Farah. Maps (East Africa – Somalia) Sia Figiel. Where We Once Belonged (Western Samoa) Amitav Ghosh. The Shadow Lines or The Glass Palace (India) Nadine Gordimer. July’s People or Burger’s Daughter (Southern Africa – South Africa) Patricia Grace. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Secrets of the Bush: Abortion in Caribbean Women’s Literary Imagination A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Leah Meagan Fry Committee in charge: Professor Maurizia Boscagli, Chair Associate Professor Teresa Shewry Associate Professor Stephanie Batiste September 2016 The dissertation of Leah Meagan Fry is approved. _____________________________________________ Stephanie L. Batiste _____________________________________________ Teresa Shewry _____________________________________________ Maurizia Boscagli, Committee Chair May 2016 Secrets of the Bush: Abortion in Caribbean Women’s Literary Imagination Copyright © 2016 by Leah Meagan Fry iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to all those who made me believe that this work was possible. From my undergraduate years, this includes Liz Barnes, my honors thesis director, Deborah Morse, and Melanie Dawson. You continue to serve as my ideal feminist academics, and you guided me to a great PhD program. To Tina Gianquitto, thank you for supporting another a literary scholar writing about women and plants. I won’t forget your kindness. Thanks to the UCSB English department and UCSB Grad Division for helping to fund my research trip to Jamaica in 2015. This research was invaluable as I framed my critical methods. Thanks to my committee: Maurizia, for your enthusiasm and encouragement; Tess, for your unwaveringly excellent notes; and Stephanie, for your incisive questions about my position as a scholar. My parents, Jake, Aunt Beth-Eireann, Karen, MR—thanks for your unwaivering support! Thank you UAW 2865-Local, without whom I would never have had the necessary time each week to do my own research. -

Poems at the Edge of Differences Universitätsverlag Göttingen Poems at the Edge of Differences New English Poetry Renatepapke Mothering in by Women

his study consists of two parts. The first part offers an overview of feminism’s the- Tory of differences. The second part deals with the textual analysis of poems about ‘mothering’ by women from India, the Caribbean and Africa. Literary criticism has dealt Renate Papke with the representation of ‘mothering’ in prose texts. The exploration of lyrical texts has not yet come. Poems at the Edge of Differences Since the late 1970s, the acknowledgement of and the commitment to difference has been fundamental for feminist theory and activism. This investigation promotes a diffe- rentiated, ‘locational’ feminism (Friedman). The comprehensive theoretical discussion of Mothering in feminism’s different concepts of ‘gender’, ‘race’, ‘ethnicity’ and ‘mothering’ builds the New English Poetry foundation for the main part: the presentation and analysis of the poems. The issue of ‘mothering’ foregrounds the communicative aspect of women’s experience and wants by Women to bridge the gap between theory and practice. This study, however, does not intend to specify ‘mothering’ as a universal and unique feminine characteristic. It underlines a metaphorical use and discusses the concepts of ‘nurturing’, ‘maternal practice’ and ‘social parenthood’. This metaphorical application supports a practice that could lead to solidarity among women and men in social and political fields. In spite of its ethical – po- litical background, this study does not intend to read the selected poems didactically. The analyses of the poems always draw the attention to the aesthetic level of the texts. Regarding the extensive material, this study understands itself as an explorative not concluding investigation placed at the intersections of gender studies, postcolonial and classical literary studies.