Henry Swanzy, the BBC, and the Development of Caribbean Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KYK-OVER-AL Volume 2 Issues 8-10

KYK-OVER-AL Volume 2 Issues 8-10 June 1949 - April 1950 1 KYK-OVER-AL, VOLUME 2, ISSUES 8-10 June 1949-April 1950. First published 1949-1950 This Edition © The Caribbean Press 2013 Series Preface © Bharrat Jagdeo 2010 Introduction © Dr. Michael Niblett 2013 Cover design by Cristiano Coppola Cover image: © Cecil E. Barker All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission. Published by the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports, Guyana at the Caribbean Press. ISBN 978-1-907493-54-6 2 THE GUYANA CLASSICS LIBRARY Series Preface by the President of Guyana, H. E. Bharrat Jagdeo General Editors: David Dabydeen & Lynne Macedo Consulting Editor: Ian McDonald 3 4 SERIES PREFACE Modern Guyana came into being, in the Western imagination, through the travelogue of Sir Walter Raleigh, The Discoverie of Guiana (1595). Raleigh was as beguiled by Guiana’s landscape (“I never saw a more beautiful country...”) as he was by the prospect of plunder (“every stone we stooped to take up promised either gold or silver by his complexion”). Raleigh’s contemporaries, too, were doubly inspired, writing, as Thoreau says, of Guiana’s “majestic forests”, but also of its earth, “resplendent with gold.” By the eighteenth century, when the trade in Africans was in full swing, writers cared less for Guiana’s beauty than for its mineral wealth. Sugar was the poet’s muse, hence the epic work by James Grainger The Sugar Cane (1764), a poem which deals with subjects such as how best to manure the sugar cane plant, the most effective diet for the African slaves, worming techniques, etc. -

The Challenges of Cultural Relations Between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean

The challenges of cultural relations between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean Lluís Bonet and Héctor Schargorodsky (Eds.) The challenges of cultural relations between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean Lluís Bonet and Héctor Schargorodsky (Eds.) Title: The Challenges of Cultural Relations between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean Editors: Lluís Bonet and Héctor Schargorodsky Publisher: Quaderns Gescènic. Col·lecció Quaderns de Cultura n. 5 1st Edition: August 2019 ISBN: 978-84-938519-4-1 Editorial coordination: Giada Calvano and Anna Villarroya Design and editing: Sistemes d’Edició Printing: Rey center Translations: María Fernanda Rosales, Alba Sala Bellfort, Debbie Smirthwaite Pictures by Lluís Bonet (pages 12, 22, 50, 132, 258, 282, 320 and 338), by Shutterstock.com, acquired by OEI, original photos by A. Horulko, Delpixel, V. Cvorovic, Ch. Wollertz, G. C. Tognoni, LucVi and J. Lund (pages 84, 114, 134, 162, 196, 208, 232 and 364) and by www.pixnio.com, original photo by pics_pd (page 386). Front cover: Watercolor by Lluís Bonet EULAC Focus has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 693781. Giving focus to the Cultural, Scientific and Social Dimension of EU - CELAC relations (EULAC Focus) is a research project, funded under the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme, coordinated by the University of Barcelona and integrated by 18 research centers from Europe and Latin America and the Caribbean. Its main objective is that of «giving focus» to the Cultural, Scientific and Social dimension of EU- CELAC relations, with a view to determining synergies and cross-fertilization, as well as identifying asymmetries in bi-lateral and bi-regional relations. -

A Review of International English Literature

ARIEL A Review of International English Literature TRIBUTE TO SAM SELVON (1923-94) SAM SELVON Extracts from Unfinished Novel and Autobiography HAROLD BARRATT Selvon's An Island Is a World FRANK BIRBALSINGH, AUSTIN CLARKE, JAN CAREW, RAMABAI ESPINET and ISMITH KHAN Selvon: A Celebration WAYNE BROWN Search for God in Selvon's Fiction KEN MCGOOGAN Saying Goodbye to Selvon KENNETH RAMCHAND Selvon's Love Songs KEVIN ROBERTS and ANDRA THAKUR Conversation with Selvon ROYDON SALICK Selvon's I Hear Thunder CLEMENT H. WYKE Selvon's Late Short Fiction EDWARD BAUGH, CYRIL DABYDEEN, KWAME DAWES, SASENARINE PERSAUD and MICHAEL THORPE Commemorative Poems SARA STAMBAUGH Review of Selvon's An Island Is a World KAREN MCINTYRE Literary Decolonization in David Dabydeen's The Intended REVIEWS BY Stella Algoo-Baksh, Matthew M. Goldstein, Marilyn Iwama, Neil Querengesser, Harry Vandervlist, Louise Yelin Volume Twenty Seven April 1996 Number Two ARIEL A REVIEW OF INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH LITERATURE ARIEL is published quarterly, in January, April, July, and October. ARIEL is a journal devoted to the critical and scholarly study of the new and the established literatures in English around the world. It welcomes particularly articles on the relationships among the new literatures and between the new and the established literatures. It publishes a limited number of original poems in each issue. Articles should not exceed 6,000 words and should follow the second edition of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers or 7¾« AÍLA Style Manual. All articles are refereed blind (authorship unattributed) by at least two readers; consequently, names of contributors should appear only on the title page of manuscripts and not as a running head on each page. -

SAM SELVON TALKING a Conversation with Kenneth Ramchand

SAM SELVON TALKING A Conversation with Kenneth Ramchand Samuel Selvon K.R. Samuel Selvon, you are the first writer-in-residence that we have had at St. Augustine and this is an important breakthrough for us, but I'm sure that many people will wonder why you are here for one month only, and why you have come in June* when our students are preoccupied with examinations. s.s. I had hoped to come for the full student term, from October to December 1982, but I'm working on a new book which I have started and I have found that some research that I'd hoped to put off till a later period has to be done right now. I can't really move with the book until the research is done. K.R. Are you doing a non-fiction work? s.s. No, but in a way it is a departure for me. I hope to do a work of fiction, but it will be based loosely — very loosely — on historical material. Although it will be in the main a fiction and invention, and will related more to human and social relationships than to events, I would like to adhere to the history of the period — roughly the 1920's and 1930's — as closely as possible. At the same time if I find that the fiction and the creativity are working to my satisfaction, I might forsake historical authenticity. In other words, if I feel the need to shift an historical event or circumstance out by a few years I might very well do so. -

Caribbean Voices Broadcasts

APPENDIX © The Author(s) 2016 171 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE BBC CARIBBEAN VOICES BROADCASTS March 11th 1943 to September 7th 1958 © The Author(s) 2016 173 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE BBC CARIBBEAN VOICES EDITORS Una Marson April 1940 to December 1945 Mary Treadgold December 1945 to July 1946 Henry Swanzy July 1946 to November 1954 Vidia Naipaul December 1954 to September 1956 Edgar Mittelholzer October 1956 to September 1958 © The Author(s) 2016 175 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE WEST INDIES FEDERATION AND THE TERRITORIES INCLUDED January 3 1958 to 31 May 31 1962 Antigua & Barbuda Barbados Dominica Grenada Jamaica Montserrat St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla St. Lucia St. Vincent and the Grenadines Trinidad and Tobago © The Author(s) 2016 177 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 CARIBBEAN VOICES : INDEX OF AUTHORS AND SEQUENCE OF BROADCASTS Author Title Broadcast sequence Aarons, A.L.C. The Cow That Laughed 1369 The Dancer 43 Hurricane 14 Madam 67 Mrs. Arroway’s Joe 1 Policeman Tying His Laces 156 Rain 364 Santander Avenue 245 Ablack, Kenneth The Last Two Months 1029 Adams, Clem The Seeker 320 Adams, Robert Harold Arundel Moody 111 Albert, Nelly My World 496 Alleyne, Albert The Last Mule 1089 The Rock Blaster 1275 The Sign of God 1025 Alleyne, Cynthia Travelogue 1329 Allfrey, Phyllis Shand Andersen’s Mermaid 1134 Anderson, Vernon F. -

The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Poetry Edited by Jahan Ramazani Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09071-2 — The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Poetry Edited by Jahan Ramazani Frontmatter More Information the cambridge companion to postcolonial poetry The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Poetry is the first collection of essays to explore postcolonial poetry through regional, historical, political, formal, textual, gender, and comparative approaches. The essays encompass a broad range of English-speakers from the Caribbean, Africa, South Asia, and the Pacific Islands; the former settler colonies, such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, especially non-Europeans; Ireland, Britain’s oldest colony; and post- colonial Britain itself, particularly black and Asian immigrants and their descen- dants. The comparative essays analyze poetry from across the postcolonial anglophone world in relation to postcolonialism and modernism, fixed and free forms, experimentation, oral performance and creole languages, protest poetry, the poetic mapping of urban and rural spaces, poetic embodiments of sexuality and gender, poetry and publishing history, and poetry’s response to, and reimagining of, globalization. Strengthening the place of poetry in postco- lonial studies, this Companion also contributes to the globalization of poetry studies. jahan ramazani is University Professor and Edgar F. Shannon Professor of English at the University of Virginia. He is the author of five books: Poetry and its Others: News, Prayer, Song, and the Dialogue of Genres (2013); A Transnational Poetics (2009), winner of the 2011 Harry Levin Prize of the American Comparative Literature Association, awarded for the best book in comparative literary history published in the years 2008 to 2010; The Hybrid Muse: Postcolonial Poetry in English (2001); Poetry of Mourning: The Modern Elegy from Hardy to Heaney (1994), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award; and Yeats and the Poetry of Death: Elegy, Self-Elegy, and the Sublime (1990). -

Vol 25 / No. 2 / November 2017 Volume 24 Number 2 November 2017

1 Vol 25 / No. 2 / November 2017 Volume 24 Number 2 November 2017 Published by the discipline of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Self-portrait with projection, October 2017, img_9723 by Rodell Warner Anu Lakhan (copy editor) Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] OR Ms. Angela Trotman Department of Language, Linguistics and Literature Faculty of Humanities, UWI Cave Hill Campus P.O. Box 64, Bridgetown, BARBADOS, W.I. e-mail: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTION RATE US$20 per annum (two issues) or US$10 per issue Copyright © 2017 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Lisa Outar Ian Strachan BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. Edited by full time academics and with minimal funding or institutional support, the Journal originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. -

Emancipation in St. Croix; Its Antecedents and Immediate Aftermath

N. Hall The victor vanquished: emancipation in St. Croix; its antecedents and immediate aftermath In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 58 (1984), no: 1/2, Leiden, 3-36 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl N. A. T. HALL THE VICTOR VANQUISHED EMANCIPATION IN ST. CROIXJ ITS ANTECEDENTS AND IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH INTRODUCTION The slave uprising of 2-3 July 1848 in St. Croix, Danish West Indies, belongs to that splendidly isolated category of Caribbean slave revolts which succeeded if, that is, one defines success in the narrow sense of the legal termination of servitude. The sequence of events can be briefly rehearsed. On the night of Sunday 2 July, signal fires were lit on the estates of western St. Croix, estate bells began to ring and conch shells blown, and by Monday morning, 3 July, some 8000 slaves had converged in front of Frederiksted fort demanding their freedom. In the early hours of Monday morning, the governor general Peter von Scholten, who had only hours before returned from a visit to neighbouring St. Thomas, sum- moned a meeting of his senior advisers in Christiansted (Bass End), the island's capital. Among them was Lt. Capt. Irminger, commander of the Danish West Indian naval station, who urged the use of force, including bombardment from the sea to disperse the insurgents, and the deployment of a detachment of soldiers and marines from his frigate (f)rnen. Von Scholten kept his own counsels. No troops were despatched along the arterial Centreline road and, although he gave Irminger permission to sail around the coast to beleaguered Frederiksted (West End), he went overland himself and arrived in town sometime around 4 p.m. -

Conference Schedule

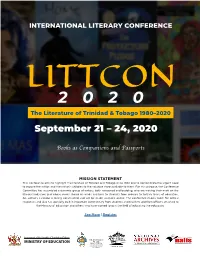

INTERNATIONAL LITERARY CONFERENCE LITTCON2020 The Literature of Trinidad & Tobago 1980–2020 September 21 – 24, 2020 Books as Companions and Passports MISSION STATEMENT This Conference aims to highlight the literature of Trinidad and Tobago since 1980 and to demonstrate the urgent need to expose the nation and the nation’s children to the valuable store available to them. For this purpose, the Conference Committee has assembled a dynamic group of writers, both renowned and budding, who are making their mark on the literary landscape and whose works should be made available to students from primary to tertiary levels of education. An author’s calendar is being constructed and will be made available online. The conference makes room for critical responses and also has specially built in important commentary from students and teachers and from officers attached to the Ministry of Education and others who have worked long in the field of educating the educators. See More | Register THE UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES ST. AUGUSTINE CAMPUS TRINIDAD & TOBAGO WEST INDIES International Literary Conference CALENDAR OF EVENTS: MONDAY 21ST SEPTEMBER, 2020 INTRODUCTION TO THE LITERARY LANDSCAPE OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Day Chair: Dr. J. Vijay Maharaj 8:00am - 8:45 am OPENING THE FRONTIERS Moderator: Dr. J. Vijay Maharaj Welcome, HOD DLCCS: Professor Paula Morgan Greetings by the Principal UWI STA: The Humanities in the 21st Century- Professor Brian Copeland Remarks from the Chairman, Friends of Mr Biswas The Conference: Structure and Purpose – Professor Kenneth Ramchand Feature Address by the Minister of Education: Dr the Honourable Nyan Gadsby-Dolly 8:45am – 9:45am THE HEART OF THE MATTER Moderator: Professor Kenneth Ramchand Presentation of the Annotated Bibliography: Ms. -

Best Performing Arts in Barbados"

"Best Performing Arts in Barbados" Created by: Cityseeker 6 Locations Bookmarked Valley Resource Centre "Community Spirit Abounds" The Valley Resource Centre is one of twelve community centers established throughout the island to provide training opportunities and other educational and vocational programs. Many of these programs are offered free of cost to members of the community in order to assist them in the development of skills such as computer training, small business by Postdlf development, arts and crafts, and some academic studies. The centers also facilitate seminars and other presentations by government departments and community-based groups. The Valley Resource Centre is located in St. George in a municipal complex which includes a police station, post office and library. -Marsilyn Browne +1 246 437 0621 The Glebe, St. George, Barbados Prince Cave Hall "And the Band Plays On" The Royal Barbados Police Force Band is one of the oldest police bands in the world, having been formed in 1889. It has a fantastic record of excellence in music and has performed throughout the world. The band has its headquarters at District A Police Station in St. Michael, which is where Prince Cave Hall is located. The hall is named for the former by Unhindered by Talent Director of Music of the Royal Barbados Police Force Band, Mr. Prince Cave. The band has a wide repertoire of music, from classical and jazz to dinner music and the latest in calypso and reggae tunes. The band also hosts several concerts each year at the Prince Cave Hall. -Marsilyn Browne +1 246 430 7603 Station Hill, St. -

George Lamming's “The Occasion for Speaking” – a Postcolonial Discourse

International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences Vol-6, Issue-2; Mar-Apr, 2021 Journal Home Page Available: https://ijels.com/ Journal DOI: 10.22161/ijels George Lamming’s “The Occasion for Speaking” – A Postcolonial discourse Smiruthi A. Assistant Professor of English, Thiagarajar College, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India Received: 17 Jan 2021; Received in revised form: 09 Mar 2021; Accepted: 19 Mar 2021; Available online: 21 Apr 2021 ©2021 The Author(s). Published by Infogain Publication. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Abstract— George Lamming is an ardent West Indian writer who has authored about six novels and numerous texts of non-fiction. His debut novel, In the Castle of My Skin (1953) became a highly popular critically acclaimed novel in the post-colonial literature. Lamming plays a crucial role in the positioning of the West-Indian writers in English literature. His astoundingly brilliant and widely controversial collection of essays, The Pleasures of Exile (1960) features the post-colonial issues faced by the West-Indians including migration, exile, identity crisis, hunger for recognition and the mixed cultural affiliations exhibited by the post-colonies. This paper tries to trace the postcolonial traits in Lamming’s essay, The Occasion for Speaking and thus, acquire a refined understanding of the thoughts and ideals of the colonized West-Indian who is in exile. Keywords—Post-colonial, migration, exile, identity, recognition. INTRODUCTION country of origin (colonies) or the country to which they “The pleasure and paradox of my own exile is have migrated (colonizers). -

Art of Wilson Harris

THE ART OF WILSON HARRIS BY MMilON C. GILLILMD A DI.^SERTATIOi:! PRESENTED TO ItlE G.R.\DUATE COUNCII OE TEE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFI1.LMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGR.ee OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY LT^TIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1982 Copyright 19B2 by Marion Charlotte Gilliland TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iv Introduction The Visionary Art of \vilson Harris 1 N otes 14 Part I Contexts of Vision Chapter 1 An Overview of the Fiction 17 Notes 35 Chapter 2 Wilson Harris in the West Indian Context 37 Notes 60 Chapter 3 The Role of Imaginaticn in Creativity 63 Notes 78 Chapter 4 Three Structuring Ideas in Wilson Harris's Fiction 81 Notes 115 Part II Visionary Texts Chapter 5 Companioas of the Day and Night 119 Note s ' 133 Chapter 6 Da Silva da Silva's Cultivated Wilderness , . 134 Notes 154 Chapter 7 Genesis of the Clowns 155 Notes c . 170 Chapter 8 The Tree of the Sun 171 Note 184 Appendix Three Interviews with Wilson Harris Synchrcnlcity 186 Shamanisiu 205 The Eye of the Scarecrow 227 Bibliography 244 Biographical Sketch 260 Xll Abstract of Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy THE ART OF WILSON HARRIS By Marion C. Gilliland December 1982 Chairman: Alistair M. Duckworth Major Department: English Wilson Harris, the Guyanese novelist, critic and poet, seeks to create new forms in the novel which will reflect his vision of the basic unity of man. This unity is free of cultural and racial ties, embodies a new state of consciousness, healed rather than divided, and is open to greater possibilities of human fulfillment for all men.