Multi-Layered Safety in Marken: a Policy Arrangement Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Holland Weekend Break

Explore North Holland Weekend Break Welcome to this weekend break full of Dutch classics! Windmills, tulips, cheese and clogs: they all pass by on this journey. Along the way you will come across the picturesque windmills of Zaanse Schans, the characteristic fishing village of Volendam, the cheese market of Edam, and historic towns such as Hoorn, Medemblik and Enkhuizen. The last day is spent in cheese ville Alkmaar, where you cycle by e-bike through an amazing sand dune landscape. In springtime the agricultural fields in this area change into a colorful patchwork quilt: full of blooming tulips! You travel by private car and driver, by train, by ferry, by bicycle and even by steam train and historic boat, all in just one weekend: a very diverse trip indeed! The best travel period to see the flowers in full bloom are the months of March, April, and May. In these months flower bulb fields burst into rows of vivid colors: a delight for the eye. Chances to see the most tulips are best in mid-April. Trip Itinerary FRIDAY - DAY 1: ZAANSE SCHANS, VOLENDAM, MARKEN, EDAM & HOORN Today you will explore the beauty of the countryside north of Amsterdam, which boasts many Dutch icons: wooden shoes, fishing, cheese and windmills! Travel to Amsterdam railway station on your own. Your private guide/driver will be waiting there for you and will firstly take you to Zaanse Schans. During the 17th century, over 600 windmills were constructed in the area around the Zaanse Schans, creating the first industrial zone. The windmills were used, among others, to grind spices, produce paint, saw wood, and produce oil. -

Walkin G Ro U

Walking route: Biking route: route: Biking 1. Sijtje Boes: In the second half of the nineteenth century, Marken was discovered by so called “Vreemden” (strangers). Just like in Volendam artists were drown to the sight of the colourful traditional clothing and the little town with its beautiful harbour, the small alleys and the many bridges. When the ‘Vreemden’ came, it meant a growing source of income from the poor Markers. There was one woman who was as first! She had a business instict and made Marken into a tourism attraction! For sixty years she shown visitors her modest typical house. The souvenir shop she also had, is still standing at Havenbuurt 21, where you can still buy your souvenirs! In 1983 Sijtje Boes died. 2. Hof van Marken: In 1903 there was a fire in Hotel de Jong, in Marken. The fire had severe consequences. The houses were all made of wood and stood so close to each other that in a short time, all nearby houses were burning. The fire department in Marken could not handle this fire alone and needed help of the department in Monnickendam. At that time, Marken was still an island, so the fire truck was loaded on a motorboat. That night it was so foggy that the boat could not find Marken, so they had to turn back. The fire destroyed many houses. After 1903 hotel de Jong was rebuild, nowadays know as Hof van Marken. This was also the place where the painters stayed to paint the pittoresk island. The Hotel was the first to receive a phone connection on Marken, everyone loved to use this! 3. -

'Locating' Holland in Two Early German Films in Early Films,' Pp

a German one in 1882, and an English one in 1885. His book gave the starting signal for 'Locating' Holland in Two Early German making the cities around the Zuiderzee a complex symbol of the Zeitgeist, combining nos- Films talgia for obsolete crafts and places that time forgot with a taste for the exotic, colourful and unknown, as signalled by the reference to oriental ism. In the beginning this discovery was one made by artists. As early as 1875 the Englishman George Clausen visited Yolendam and Marken with Havard's travel book in his In the Desmet collection of the Nederlands Filmmuseum, two remarkable German fiction hand, and a little later, partly due to exhibitions of work by Dutch and foreign artists, the films can be found, DES MEERES UND DER LIEBE WELLEN (1912) and AUF EINSAMER INSEL upcoming tourist industry seized on such places. Yolendam in particular became an obliga- (1913). Each was shot in a well-known Dutch tourist attraction: Yolendam, where Christoph tory excursion for each foreign tourist visiting the Netherlands. At the same time, in Yolen- MUlleneisen filmed DES MEERES UND DER LIEBE WELLEN for Dekage, and the Island of dam, as in other Dutch locations like Laren, Domburg and Bergen, a true artists' colony 2 Marken, where Joseph Delmont did location work for AUF EINSAMER INSEL, an Eiko pro- sprang up and stayed there until the outbreak of World War 1. duction. These two German' adventures' in the Netherlands are no isolated cases, for they are part of larger trends: the emergence of artists' colonies at sites of outstanding beauty, and Spaander the simultaneous expansion of cross-border tourism at the turn of the century. -

CT4460 Polders 2015.Pdf

Course CT4460 Polders April 2015 Dr. O.A.C. Hoes Professor N.C. van de Giesen Delft University of Technology Artikelnummer 06917300084 These lecture notes are part of the course entitled ‘Polders’ given in the academic year 2014-2015 by the Water Resources Section of the faculty of Civil Engineering, Delft University of Technology. These lecture notes may contain some mistakes. If you have any comments or suggestions that would improve a reprinted version, please send an email to [email protected]. When writing these notes, reference was made to the lecture notes ‘Polders’ by Prof. ir. J.L. Klein (1966) and ‘Polders and flood control’ by Prof. ir. R. Brouwer (1998), and to the books ‘Polders en Dijken’ by J. van de Kley and H.J. Zuidweg (1969), ‘Water management in Dutch polder areas’ by Prof. dr. ir. B. Schulz (1992), and ‘Man-made Lowlands’ by G.P. van der Ven (2003). Moreover, many figures, photos and tables collected over the years from different reports by various water boards have been included. For several of these it was impossible to track down the original sources. Therefore, the references for these figures are missing and we apologise for this. We hope that with these lecture notes we have succeeded in producing an orderly and accessible overview about the genesis and management of polders. These notes will not be discussed page by page during the lectures, but will form part of the examination. March 2015 Olivier Hoes i Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Geology and soils of the Netherlands 3 2.1 Geological sequence of soils -

Marken, Dreven, Kanten En Pieren April 2008

Colofon Uitgave Marken, dreven, kanten en pieren April 2008 Tekst Brenda Scholten 40 JAAR NAAMGEVING IN ALMERE Vormgeving gemeente Almere SBZ, Communicatie/Vormgeving Foto’s Bun Projectontwikkeling Lionel Goyet Jos Jongerius Ton Kastermans Stadsarchief Geert van der Wijk Witho Worms Arne Zwart Drukwerk Koninklijke Broese & Peereboom ISBN nummer 978-90-813003-1-5 Oplage 4.500 Almere of Almère? Sticht? Waar is dat? Waar ligt toch dat Buitenland in Almere Buiten? Wat voor dans is een Karoen? Weet Marlene Dietrich van ‘haar’ straat? En moeten we het Aan de teksten van dit boekje kunnen echt weer over de Brommy en Tommystraat hebben? Wie bedenkt zoiets eigenlijk?! geen rechten worden ontleend. Marken, dreven, kanten en pieren 40 JAAR NAAMGEVING IN ALMERE Brenda Scholten in opdracht van de gemeente Almere (Stadsarchief en Stadsbeheer) [inhoud] Hoofdstuk 1 Prille polder (1968 – 1970) 8 [thema] Kijkje in de keuken Hoofdstuk 2 Van RIJP naar ZIJP (1970 – 1978) 14 [thema] Marken, dreven, kanten en pieren Hoofdstuk 3 Veilige namen, geen nummers (1978 – 1984) 19 [thema] Ieder pad, iedere brug [thema] What’s in a name? Hoofdstuk 4 Muziek, film, dans 31 [thema] Brainstormen op open zee Hoofdstuk 5 Verhalen uit de grote stad (1996 – 2004) 41 [thema] Rockers, filmsterren en striphelden?! Hoofdstuk 6 De veelbesproken Stripheldenbuurt (2004 – 2007) 47 [thema] Dilemma’s en discussies [thema] Nummers, naamborden en kaarten Hoofdstuk 7 Bruisend centrum en Almere Poort 57 [thema] Het streepje legt het loodje [thema] Naamgeving in beweging Met dank aan 68 Marken, dreven, kanten en pieren 3 4 40 jaar naamgeving in Almere [voorwoord] Almere schrijft geschiedenis, iedere dag. -

Images in Tourism and Consumer Culture

CHAPTER 6 Selling a “Dutch Experience”: Images in Tourism and Consumer Culture Dellmann, Sarah, Images of Dutchness. Popular Visual Culture, Early | 265 Cinema, and the Emergence of a National Cliché, 1800-1914. Amsterdam University Press, 2018 doi: 10.5117/9789462983007_ch06 ABSTRACT This chapter investigates early tourist discourse (1875-1914) on the Nether- lands through material of mostly British, German, and Dutch origin – travel brochures from Thomas Cook, the Vereeniging voor Vreemdelingenverkeer (VVV), and the Centraal Bureau voor Vreemdelingenverkeer, as well as guide- books and travel writings. It traces the emergence of commercial tourism to the Netherlands by bringing together earlier forms of leisure travel to the Netherlands and the discovery of the Netherlands as a place worthwhile visit- ing by painters and writers of the Romanticist movement. In tourist discourse, information is linked to the advertising or purchase of a service or commod- ity – a travel arrangement, a postcard, or a souvenir. These commodities serve as mediators for experiencing the visited country; hence other visual media of consumer culture are investigated as well (advertising trade cards, picture post- cards). Images in tourist discourse and consumer culture mostly use the form of the cliché, regardless if these images were produced by Dutch or foreign peo- ple. The chapter concludes with a discussion of Dutch reactions to the cliché, which calls for rethinking the divide between self-image and outsiders’ image. KEYWORDS visual culture; consumer culture; tourism; visual media; nineteenth century; twentieth century; cliché; self-image and outsider’s image; landscape paint- ing; Romanticism; Picturesque 6.1 INTRODUCTION: DISCOVERING THE AUTHENTIC Information from promotional material in tourist discourse is often met with suspicion. -

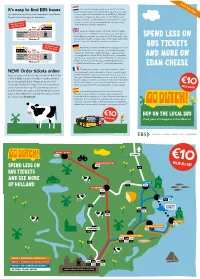

Spend Less on Bus Tickets and More on Edam Cheese

Take for free Het echte Holland ligt letterlijk om de hoek! Een Holland It’s easy to find EBS buses zonder hordes toeristen en met vriendelijke locals. Wees een echte You can find them at the rear of Amsterdam Central Station. local en ontdek het Hollandse Holland met de EBS bus. En binnen Buy your tickets directly at the bus station. enkele minuten krijgt u een persoonlijke tour door Marken, eet u een pannenkoek in een authentiek pannenkoekenhuis in Volendam of vaart u in een bootje tussen de indrukwekkende huizen uit de Situation until zeventiende eeuw in Broek in Waterland. July 13th 2014 Exit Bus stop Water side Escape the tourists and go local! Head out into the Dutch Amsterdam Central countryside on one of Holland’s loveliest bus routes, taken by local Station Amsterdammers every day. In just minutes, you’ll find yourself riding spend less on City side Entrance along century-old dikes, eating pancakes in tiny villages and boating past the homes of Holland’s 17th century rich and famous. Situation from bus tickets S t July 13th 2014 Entfliehen Sie dem Touristen-Rummel und machen Sie es wie a i Bus stop r s Exit die Einheimischen! Fahren Sie auf einer der schönsten Busrouten Water side Hollands, die Amsterdamer täglich zurücklegen, aufs Land. Nach Amsterdam nur weniger Minuten können Sie mit dem Fahrrad an Jahrhunderte and more on Central Station alten Deichen entlang fahren, köstliche Pfannkuchen in malerischen Dörfern genießen und vom Boot aus die Wohnsitze der Reichen Entrance City side und Berühmten Hollands aus dem 17. -

The Struggle for the Markerwaard

The Struggle for the Markerwaard An analysis of changing socio-technical imaginaries on land reclamation during the late 20th century in the Netherlands 1 Final research master thesis Author: Siebren Teule Supervisor: dr. Liesbeth van de Grift Research-master History Utrecht University Word-count: 36749, excluding footnotes and bibliography) Date: July 17th, 2020 Front-page images: Figure above: The monument on the Enclosure Dam, commemorating the Zuiderzee construction process. It depicts the labourers who worked on the Dam, and a now-famous phrase: A living people build their own future (‘Een volk dat leeft bouwt aan zijn toekomst’).1 Figure below: While airplanes fly across carrying banners with slogans against the reclamation, the last gap in the Houtribdijk between Enkhuizen and Lelystad is closed in the presence of minister Westerterp (TWM) on September 4th, 1975.2 1 Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Afsluitdijk_monument.jpg. 2 Photo: Dick Coersen (ANP), Nationaal Archief/Collectie Spaarnestad. 2 Acknowledgements This thesis is the final product of six months of research, and two years of exploring my own interests as part of Utrecht University’s research-master History. During the past months, I have found the particular niches of historical research that really suit my research interests. This thesis is neatly located in one of these niches. The courses, and particularly my internship at Rijkswaterstaat in the second half of 2019, aided me greatly in this process of academic self-exploration, and made this thesis possible. There are many people who aided me in this process, either by supervising me or through discussions. -

Jo Spier, Dutch National Identity, and the Marshall Plan in the Netherlands

Educating the Nation: Jo Spier, Dutch National Identity, and the Marshall Plan in the Netherlands Mathilde Roza Introduction In the visual history of the Marshall Plan, the image of a Dutchman climbing the U.S. Dollar sign to a more prosperous future is well-known and holds a prominent place in the history of the Marshall Plan to the Netherlands. The iconic image (see figure 1) appeared on the cover of a small booklet, Het Marshall-Plan en U (The Marshall Plan and You) which had been designed and illustrated by Dutch artist Jo Spier, a well- known and highly popular illustrator in the Netherlands in the period before WWII, and regarded by many as one of the best, if not the best, illustrator of his time (Van der Heyden 13). Published in November 1949, the booklet saw a second edition in March 1950, a third one in May of the same year, and reached an estimated 2,5 mil- lion Dutch people (one- fourth of the Dutch population at that time).1 Also, after its successful appearance in the Netherlands, the booklet was trans- lated into English2 and was used in the United States to a very similar pur- pose: while the Dutch were being educated about the benefits of accepting American aid and the necessity for European cooperation, the American people, many of whom were opposed to the project, likewise needed to be educated on the goals and practices of the Marshall Plan and persuaded 1 The booklet’s success is also illustrated by the fact that an exhibition on the Marshall Plan in the Netherlands, which opened in Amsterdam in early 1951, was entitled “Het Marshall- Plan en U” (See for instance IJmuider Courant, 5 maart 1951, 2. -

Dutch Towns to Visit During Coronacation

Dutch Towns to Visit During Coronacation By Ellerbe Mendez 1. Giethoorn Giethoorn Overview Province: overijssel Known for: It is mostly car-free village filled with waterways and bike paths and traditional, centuries old, thatched roof houses. It is known as “Dutch Venice. It is nearby the Weerribben-Wieden National Park that has beautiful marshes we can also visit. Giethoorn Location Giethoorn is about an hour and 33 minute drive from Haarlem, and is 141 km away. 2. Volendam Volendam Overview Province: North Holland Known For: Volendam is a fishing town northeast of here located on a Markermeer Lake. It is known for beautiful colorful houses and it’s harbour. Volendam location Volendam is about a 40 minute drive from Haarlem and about 45 km away. 3. Marken Marken Overview Province: North Holland Known for: Marken is a village that was an island but now turned into a peninsula. It is on the same Lake Markermeer as Volendam. It’s wooden houses have been a tourist attraction. Marken Location Marken is a 41 minute drive from Haarlem and 47 km away 4. Kinderdijk Kinderdijk Overview Province: South Holland Known For: It has 19 iconic 18th century windmills! It has several trails for walking and biking and waterways. Kinderdijk Location Kinderdijk is a 1 hour and 13 minute drive from Haarlem and 104 km away. 5. Broek in Waterland Broek in Waterland Overview Province: North Holland Known For: Broek in Waterland is a small village with colorful homes and flowers and waterways. Broek in Waterland Location Broek in Waterland is a 30 minute drive from Haarlem and it is 35 km away. -

Northern Route – Top of Amsterdam Holland - Bike and Barge Tour

Northern Route – Top of Amsterdam Holland - Bike and Barge Tour This tour begins and ends in Amsterdam but will take you north to the distinctly rural Island of Texel after visits to the architectural jewels of Edam, Hoorn, Enkhuizen and Alkmaar, as well as the fascinating outdoor museum, Zaanse Schans. In the 17th century this extensive area was recovered from the sea with the use of hundreds of windmills - many still in working order today. You will get a strong sense of the 17th century Dutch prosperity in Enkhuizen, Hoorn and Volendam. Later, you’ll sail to Texel, an island with thousands of sheep and a magnificent nature preserve that makes it a bird lover’s paradise. Back on the mainland, the route will take you over small dikes and quiet country roads through vast polders and along beautiful sand dunes stretching from Schoorl to Bergen. Alkmaar is the capital of cheese making and has its own cheese market and historic Waag (weigh house). In the tulip months of April and May, you will also cycle through miles of colorful fields. Included in the Tour Price • 7 nights on board the ship (sheets, blankets, and two towels) • 7 breakfasts, 6 packed lunches, and 7 dinners • Coffee and tea on board • 24-speed bicycle, incl. helmet, pannier bags, lock, water bottle, and bike insurance • Tour guide (multilingual) • Route information and road book • Ferry fares on the route • Reservation costs Daily Itinerary Saturday: Amsterdam – 9 miles (15 km) On Saturday afternoon you will be expected by 4 p.m. on your boat located close to the Amsterdam Central Station. -

How to Get to Zaanse Schans

Enkhuizen Heerhugowaard Bus Station Hoorn Centrum Bus stop OLD Public Transport Map G 314 Alkmaar Railway HOLLAND Bicycle route 6 0 1 2 3 4 5 km Amsterdam Area map & day trips 314 9 Visitor Centres & Highlights a I amsterdam Visitor Centre Only e 30 mins from S Central Station or Amsterdam Airport Schiphol Amsterdam Beemster iamsterdam.com/area h t A VVV I-point Wormer (zaans.nl) r De Rijp Graft-De Rijp o B VVV Edam (vvv-edam.nl) N 305 C VVV Volendam (vvv-volendam.nl) Alkmaarder- Middenbeemster D VVV Monnickendam (vvvwaterland.nl) VVV Middenbeemster meer 305 E De Buurt M E (laagholland.com) F VVV Purmerend (laagholland.com) 314 a G VVV Alkmaar (vvvalkmaar.nl) 305 The Zaanstore F rk H (zaans.nl) *only during summer e Highlights 817* Uitgeest Busstation Edam r Industrial Wall, Wormer Purmerend Overwhere m Zaandam City Centre 110 314 316 817* Purmerend *only during summer e Czar Peter House 110 e Zaanse Schans Tramplein Korenstraat 817* B r www.iamsterdam.com/area 110 110 316 Zaans Museum 307 817* 110 305 Station 314 De Kraai Pancake Restaurant A 817* Inntel Hotels Amsterdam Zaandam Volendam Centrum Wormer C MonetAtelier Wormer, Nieuweweg 316 Alida Hoeve Cheese Farm 67 Purmerend Weidevenne 307 817* Wormerveer Volendam Jacobs Hoeve Cheese Farm 110 316 817* 817* *only during summer Alkmaar Cheese Market 15 *only during summer min Marinapark Zuiderzee Museum Museum Steamtram Hoorn-Medemblik Zaanse Schans 13 314 Station Zaandijk Zaanse Schans 305 Fort Resort Beemster 316 D 67 391 817* 891* 307 Zaanferry (ferry service) *only during summer 15 Marken Oud Zaandijk 391 12 Monnickendam Broek in Waterland Zaandam 55 Marken Centrum Zaanstreek Kogerveld Monnickendam Het 315 Overleek Tea Garden 17 Twiske Swaensborch 16 Zaandam H 315 Broek in Waterland 392 Landsmeer Station Zaandam 394 1 Amsterdam & Region Travel Ticket (ARTT) Spaarnwoude 391 20 EXPLORE 67 392 394 392 *only during summer 314 Get out of Amsterdam with the ARTT, which grants you 394 891* 37 315 41 316 unlimited travel on the city’s public transportation and beyond.