World War I, the Committee on Public Information, and the Effectiveness of Good Poster Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missouri Historical Review

Historiostl ZR,evie*w BOYS and GIRLS! Tlbu can helpyour Uncle Sam Win the War Save jyour Quarters Buy War Savings Stamps The State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI HgisiSllill^ The front cover illustration is one of artist-author M James Montgomery Flagg's World War I patriotic posters, g] Flagg, born in 1877, studied at the Art Students League M in New York and at Herkomer's Art School in Bushey, M England; he later studied with Victor Marec of Paris. An illustrator for various magazines including St. Nicholas Magazine, Judge and Life, Flagg's portrait paintings were exhibited at the Paris Salon and the National Academy of Design. He prepared patriotic posters during both World Wars. His writings include the books: Yankee Girls Abroad, Why They Married, City People and the autobiographical H Roses and Buckshot. Flagg died on May 27, 1960. || Flagg's poster is one of many varied items in the So- M ciety's latest gallery and corridor exhibition entitled, "Con- [§] flict: Men, Events and Artists." Among the artists and || lithographers included in the exhibition are: George Caleb jS Bingham, Thomas Hart Benton, Daniel R. Fitzpatrick, S. J. H Ray, George Wilhelm Fasel, Louis Kurz, Alexander Allison, g| Gladys Wheat and William Knox. Paintings, lithographs, B posters and drawings are some of the items constituting SI the exhibit. "Conflict: Men, Events and Artists" can be n viewed Monday through Friday, 8:00 a.m.-4:30 p.m. M m MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW Published Quarterly by THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI COLUMBIA, MISSOURI RICHARD S. -

New Exhibition the American Muse Debuts at the Nmai

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 2, 2013 Contact: Eric Brocklehurst Tel: (401) 851-8949 ext. 18 Email: [email protected] Website: www.americanillustration.org NEW EXHIBITION ‘THE AMERICAN MUSE’ DEBUTS AT THE NMAI NEWPORT, RI- Friday, May 24, the NMAI officially debuts its new exhibition, The American Muse. The exhibition is in homage to American women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and the illustrators who accurately portrayed the quintessential yet distinctly American feminine beauty that these women embodied. The American illustrators highlighted include Charles Dana Gibson, Harrison Fisher, and others of the greatest illustrators of the period, such as: Philip Boileau, MacClelland Barclay, Howard Chandler Christy, James Montgomery Flagg, Henry Hutt, Walter Granville Smith, Paul Stahr, and Albert Beck Wenzell. Each of these illustrators created their own prototypical image of ‘The American Woman.’ The public gave these illustrators’ artworks generic names as part of their respective oeuvre; The Gibson Girl and The Fisher Girl stand out as the most popular of all. These renditions of the illustrators’ ideal woman captured the increasingly independent spirit of American women. The illustrations both shaped and reflected American society and its notions of female beauty. Compared to women of previous eras, these women relished more freedoms, enjoyed greater opportunities in sports and education, and were at the vanguard of a time when women effected change through social and political movements on an unprecedented scale in Western culture. Also showing at the NMAI are Maxfield Parrish: The Retrospective, which has been extended due to popular demand through Fall 2013, and Howard Pyle & His Brandywine Students, showcasing the works of Howard Pyle, N.C. -

The Art of Staying Neutral the Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918

9 789053 568187 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 1 THE ART OF STAYING NEUTRAL abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 2 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 3 The Art of Staying Neutral The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918 Maartje M. Abbenhuis abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 4 Cover illustration: Dutch Border Patrols, © Spaarnestad Fotoarchief Cover design: Mesika Design, Hilversum Layout: PROgrafici, Goes isbn-10 90 5356 818 2 isbn-13 978 90 5356 8187 nur 689 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2006 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 5 Table of Contents List of Tables, Maps and Illustrations / 9 Acknowledgements / 11 Preface by Piet de Rooij / 13 Introduction: The War Knocked on Our Door, It Did Not Step Inside: / 17 The Netherlands and the Great War Chapter 1: A Nation Too Small to Commit Great Stupidities: / 23 The Netherlands and Neutrality The Allure of Neutrality / 26 The Cornerstone of Northwest Europe / 30 Dutch Neutrality During the Great War / 35 Chapter 2: A Pack of Lions: The Dutch Armed Forces / 39 Strategies for Defending of the Indefensible / 39 Having to Do One’s Duty: Conscription / 41 Not True Reserves? Landweer and Landstorm Troops / 43 Few -

View / Open Thesis Final-Bisson.Pdf

NO LAUGHING MATTER: XENOPHOBIA AND ANTI-RADICALISM IN EARLY AMERICAN POLITICAL CARTOONS by BIANCA RENEE BISSON A THESIS Presented to the Department of Political Science and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2014 An Abstract of the Thesis of Bianca Renee Bisson for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Political Science to be taken June 2014 Title: No Laughing Matter: Xenophobia and Anti-Radicalism in Early American Political Cartoons Approved: __d_---l ~--~--------- Anita Chari While political cartoons have a reputation for upholding the tenants of democracy and freedom, the editorial images of the late 19th century and early 20th century show quite the contrary. In fact, they promote elements of early American life such as racism, misogyny and anti-radicalism, and make negative statements about the aspects of society that did not conform to conservative White Anglo-Saxon Protestantism. [j Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank my thesis advisors, Professors Anita Chari, Alison Gash, and Casey Shoop. Professor Chari is a wonderful instructor, whose class on radical political theory motivated me to continually think critically about the world. Professor Gash teaches in a captivating way that drove me to question the status quo from a legal perspective. Professor Shoop, though I have not had the chance to take a class from him, made me feel at ease and comfortable despite the often high demands of the Clark Honors College. I would also like to thank my parents for supporting my education from afar and my friends for creating a safe and warm environment to come home to at the end of a long day of studying. -

World War I Posters from the Newark Public Library

World War I Posters from the Newark Public Library 1 For Home and Country: World War I Posters from the Newark Public Library September 11 – December 13, 2017 University Galleries William Paterson University Inside front cover Clockwise from top left Exhibition checklist 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 10 2 polished publication. He was patient and diligent while Introduction offering fresh perspectives on these historical prints. Special thanks go to William Paterson University Kristen Evangelista Director, University Galleries President Dr. Kathleen Waldron, Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs Dr. Warren Sandmann, Associate Provost for Academic Affairs Dr. Sandra Hill, former Associate Provost for Academic Affairs Dr. Stephen Hahn, Dean of the College of the Arts and Communication Daryl J. Moore, Associate Dean of the College of the Arts ome of our nation’s most iconic First and foremost, I would like to thank WP Professor of and Communication Loretta McLaughlin Vignier, and Chair images were created as propaganda History George Robb for his unwavering cooperation, vision, of the Art Department Professor Lauren Razzore. during World War I. From 1917-1918, and dedication to realizing this exhibition and publication. I would like to especially thank the entire gallery staff S several hundred artists worked This significant undertaking reflects his astute judgment, for their hard work and commitment to all that we do. diligently in concert with government focused scholarship, and curatorial expertise. Emily Johnsen adeptly coordinated numerous aspects agencies to design posters that supported the nation, We received indispensable guidance from Professor of the exhibition and publication with a constant eye for upheld values of liberty, and promoted participation in Alejandro Anreus and Professor Thomas Uhlein in the re- detail. -

Contrasting Portrayals of Women in WW1 British Propaganda

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2015 Vol. 13 of history, propaganda has been aimed at patriarchal Victims or Vital: Contrasting societies and thus, has primarily targeted men. This Portrayals of Women in WWI remained true throughout WWI, where propaganda came into its own as a form of public information and British Propaganda manipulation. However, women were always part of Stacey Reed those societies, and were an increasingly active part History 385 of the conversations about the war. They began to be Fall 2014 targeted by propagandists as well. In war, propaganda served a variety of More than any other war before it, World War I purposes: recruitment of soldiers, encouraging social invaded the every day life of citizens at home. It was the responsibility, advertising government agendas and first large-scale war that employed popular mass media programs, vilifying the enemy and arousing patriotism.5 in the transmission and distribution of information from Various governments throughout WWI found that the the front lines to the Home Front. It was also the first image of someone pointing out of a poster was a very to merit an organized propaganda effort targeted at the effective recruiting tool for soldiers. Posters presented general public by the government.1 The vast majority of British men with both the glory of war and the shame this propaganda was directed at an assumed masculine of shirkers. Women were often placed in the role of audience, but the female population engaged with the encouraging their men to go to war. Many propaganda messages as well. -

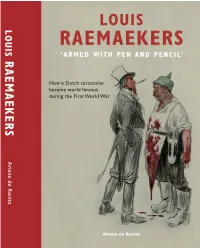

Raemaekers-EN-Cont-Intro.Pdf

LOUIS RAEMAEKERS ‘ARMED WITH PEN AND PENCIL’ How a Dutch cartoonist became world famous during the First World War Ariane de Ranitz followed by the article ‘The Kaiser in Exile: Wilhelm II in Doorn’ Liesbeth Ruitenberg Louis Raemaekers Foundation 0.Voorwerk 1-21 Engels.indd 3 17-09-14 15:57 Table of Contents Preface and Acknowledgments 9 4 The war: anti-neutrality 75 Introduction 13 (1914–1915) Sources 16 The first weeks of the war 75 Rumours 75 1 Youth in Roermond 23 Belgian refugees 77 (1869–1886) War reporting 79 The Raemaekers family 23 Raemaekers’ response to the German invasion 82 Conflict between liberals and clericals 24 The attitude of the Dutch press 86 Roermond newspapers 26 Raemaekers and De Telegraaf 88 Joseph Raemaekers enters the fray 28 Violation of neutrality 88 De Volksvriend closes down 30 The attitude of De Telegraaf 90 Louis learns to draw 31 First album and exhibitions 93 Cultural life dominated by the firm of Cuypers 33 More publications 98 Neutrality in danger 100 2 Training and work as drawing teacher 35 A price on Raemaekers’ head? 103 (1887–1905) Schröder goes to jail 107 Drawing training in Nijmegen, Roermond More frequent cartoons; subjects and fame 108 and Amsterdam 35 First appointment as a drawing teacher 37 5 Raemaekers becomes famous abroad 115 Departure for Brussels 38 (1915–1916) Appointment in Wageningen 38 Distribution outside the Netherlands 115 Work as illustrator and portrait painter 44 International fame 121 Marriage and children 47 London 121 Children’s books 50 Exhibition at the Fine Art Society -

Our Lady of Antwerp

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons Faculty Publications LSU Libraries 2018 Sacred vs. Profane in The Great War: A Neutral’s Indictment Marty Miller Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/libraries_pubs Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Marty, "Sacred vs. Profane in The Great War: A Neutral’s Indictment" (2018). Faculty Publications. 79. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/libraries_pubs/79 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the LSU Libraries at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sacred vs. Profane in The Great War: A Neutral’s Indictment Louis Raemaekers’s Use of Religious Imagery in Adoration of the Magi and Our Lady of Antwerp by Marty Miller Art and Design Librarian Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, Louisiana t the onset of the First World War in August 1914, Germany invaded France and Belgium, resulting in almost immediate British intervention and provoking a firestorm of protest throughout Western Europe. Belgium’s Asmall military was overmatched and reduced to fighting skirmishes as the Kaiser’s war machine headed toward France. Belgian civilians, as they had during the Franco- Prussian War, resisted by taking up arms. Snipers and ambushes slowed the Germans’ advance. In retaliation, German troops massacred Belgian men, women, and children. Cities, villages, and farms were burned and plundered.1 Belgian neutrality meant nothing to the German master plan to invade and defeat France before the Russian army could effectively mobilize in the east. -

Papers/Records /Collection

A Guide to the Papers/Records /Collection Collection Summary Collection Title: World War I Poster and Graphic Collection Call Number: HW 81-20 Creator: Cuyler Reynolds (1866-1934) Inclusive Dates: 1914-1918 Bulk Dates: Abstract: Quantity: 774 Administrative Information Custodial History: Preferred Citation: Gift of Cuyler Reynolds, Albany Institute of History & Art, HW 81-20. Acquisition Information: Accession #: Accession Date: Processing Information: Processed by Vicary Thomas and Linda Simkin, January 2016 Restrictions Restrictions on Access: 1 Restrictions on Use: Permission to publish material must be obtained in writing prior to publication from the Chief Librarian & Archivist, Albany Institute of History & Art, 125 Washington Avenue, Albany, NY 12210. Index Term Artists and illustrators Anderson, Karl Forkum, R.L. & E. D. Anderson, Victor C. Funk, Wilhelm Armstrong, Rolf Gaul, Gilbert Aylward, W. J. Giles, Howard Baldridge, C. LeRoy Gotsdanker, Cozzy Baldridge, C. LeRoy Grant, Gordon Baldwin, Pvt. E.E. Greenleaf, Ray Beckman, Rienecke Gribble, Bernard Benda, W.T. Halsted, Frances Adams Beneker, Gerritt A. Harris, Laurence Blushfield, E.H. Harrison, Lloyd Bracker, M. Leone Hazleton, I.B. Brett, Harold Hedrick, L.H. Brown, Clinton Henry, E.L. Brunner, F.S. Herter, Albert Buck, G.V. Hoskin, Gayle Porter Bull, Charles Livingston Hukari, Pvt. George Buyck, Ed Hull, Arthur Cady, Harrison Irving, Rea Chapin, Hubert Jack. Richard Chapman, Charles Jaynes, W. Christy, Howard Chandler Keller, Arthur I. Coffin, Haskell Kidder Copplestone, Bennett King, W.B. Cushing, Capt. Otho Kline, Hibberd V.B Daughterty, James Leftwich-Dodge, William DeLand, Clyde O. Lewis, M. Dick, Albert Lipscombe, Guy Dickey, Robert L. Low, Will H. Dodoe, William de L. -

Gra2151c: Fall 2013 Syllabus

Syllabus GRA2151c: Illustration Tuesday & Thursday, 2:30 pm – 5:15 pm, VAB 213B Instructor: Matthew Dunn | Office: CAH 190N | E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: W, 4:00 pm - 5:30 pm. Contact me for appointment. Course Overview: This course is an introduction to various traditional mediums and techniques of illustration. Each assignment will focus on understanding the medium as well as tackling basic illustration concerns such as composition, staging, layout, fundamentals of drawing, anatomy, perspective, color, and conceptual thinking. Required Book: 5.5” x 8.5” spiral sketchbook, 100 pages (such as Strathmore or Canson) Grade Breakdown: Grades will be based on mastery of the medium, composition, drawing fundamentals, and overall structure of the illustrations. Projects 1-6 600 Grade Scale (6 @ 100 points each) 900-933: A- 934-1000: A Final Project 200 800-833: B- 837-866: B 867-899: B+ Sketchbook 100 700-733: C- 737-766: C 767-799: C+ Pop Assignments 100 600-633: D- 637-666: D 667-699: D+ Below 600 points: F Maximum 1000 Points Sketchbook: Your sketchbook will be used throughout the semester to develop concepts (thumbnails, drafts, etc.) for your projects as well as for in-class assignments. It will be turned in during the final exam period. You may paste related drawings into sketchbook, but it should be done in a neat manner. Loose drawings, folders, and portfolios or other oversized pieces will not be accepted. In-Class Assignments: You will be given a series of in-class “pop”-assignments throughout the semester. The goal of these assignments is to help you hone your conceptual skills and come up with quick ideas and solutions to problems. -

World War I Posters and the Female Form

WORLD WAR I POSTERS AND THE FEMALE FORM: ASSERTING OWNERSHIP OF THE AMERICAN WOMAN LAURA M. ROTHER Bachelor of Arts in English John Carroll University January, 2003 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTERS OF ARTS IN HISTORY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2008 This thesis has been approved for the Department of ART HISTORY and the College of Graduate Studies by ___________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Samantha Baskind _________________________ Department & Date ____________________________________________ Dr. Marian Bleeke ________________________ Department & Date _____________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Lehfeldt ___________________________ Department & Date WORLD WAR I POSTERS AND THE FEMALE FORM: ASSERTING OWNERSHIP OF THE AMERICAN WOMAN LAURA M. ROTHER ABSTRACT Like Britain and continental Europe, the United States would utilize the poster to garner both funding and public support during World War I. While war has historically been considered a masculine endeavor, a relatively large number of these posters depict the female form. Although the use of women in American World War I visual propaganda may not initially seem problematic, upon further inspection it becomes clear that her presence often served to promote racial and national pretentiousness. Based on the works of popular pre-war illustrators like Howard Chandler Christy and Charles Dana Gibson, the American woman was the most attractive woman in the in the world. Her outstanding wit, beauty and intelligence made her the only suitable mate for the supposed racially superior American man. With the onset of war, however, the once entertaining romantic scenarios in popular monthlies and weeklies now represented what America stood to lose, and the “American Girl” would make the transition from magazine illustrations to war poster with minimal alterations. -

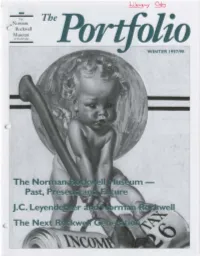

The No Past, J.C

T-he The e Nonnan " Rockwell Museum at Stockbridge to WINTER 1997/98 The No Past, J.C. Leye 2 Far right, Marge Ceder, museum employee for 22 years, shares a laugh with director Laurie Norton Moffatt and board president David Klausmeyer. Right, former board member Stockbridge Police Chi ef Richard Wilcox and his wife Dr. Joyce Butler chat witll trustee emeritus Norma Ogden. The Norman Rockwell Museum Celebrations! Board of Trustees David L. KJausmeyer President In September, the Norman Rockwell Museum held a wonderful party to Bobbie Crosby First Vice-President celebrate the accreditation by the American Association of Museums and at Steven Spielberg Second Vice-President Perri Petricca Treasurer the same time honored fifteen staff members who have been with the mu Rosell e Kline Chartock Clerk seum from 10 to 22 years. William M. Bulger Timothy R. McLevish James A. CUlUlingham Thomas Patti Daniel DuBois LincoLl Russell Joan SerVaas Durham Joseph M. Sa lvadore Michell e Gillett Mark Selkowitz Neil and Jane Golub Brian J. Quinn Elaine S. Gunn Aso Tavitian James W. Ireland Laughran S.vaber Harvey C het Krentzman Lee W ill iams ( Robert F. McDermott Jamie Williamson Trustees Emeriti Lila Wilde Berl e Jane P. Fitzpatrick John M. Deely, J r. Norm a G. Ogden H enry 1-1. Wilhams, Jr. Former board member Jack Batty enjoyed llie evening along willi his Laurie Norton Moffatt, Director momer Margaret, who was one of me museum's early directors. The Norman Rockwe ll Museum is funded in part by the M assachusetts Cultural Cowlcil, a state Below, new trustee Will iam Bulger agency that supports public programs in the arts, willi his wife Mary attended tlle humanities, and sciences.