Wittenberg History Journal Spring 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danske Studier

DANSKE STUDIER GENERALREGISTER 1904-1965 AKADEMISK FORLAG KØBENHAVN Indhold Indledning 5 Forkortelser 7 I. Alfabetisk indholdsfortegnelse A. Afhandlinger og artikler 9 B. Anmeldelser 37 C. Meddelelser 53 II. Litteraturforskning A. Genrer, perioder, begreber 54 B. Stilistik 57 C. Verslære, foredragslære 58 D. Forfatter- og værkregister 60 Anonymregister 98 III. Sprogforskning A. Sprogforskning i alm., dansk og fremmed sproghistorie, blandede sproglige emner 103 B. Fonetik, lydhistorie, lydsystem 107 C. Grammatik: morfologi, syntaks 109 D. Runologi 111 E. Dialekter 113 F. Navneforskning 1. Stednavne 114 2. Personnavne 121 3. Mytologiske og sagnhistoriske navne 123 G. Behandlede tekster og håndskrifter 124 H. Behandlede ord 126 IV. Folkeminder og folkemindeforskning A. Historie, metode, indsamling 136 B. Skik og brug, fester 136 C. Folketro, folkemedicin, religionshistorie, mytologi 1. Folketro 138 2. Folkemedicin 141 3. Religionshistorie 141 4. Mytologi 142 D. Episk digtning, folkedigtning 1. Heltedigtning, heltesagn, sagnhistorie 144 2. Folkeeventyr, fabler 145 AT-nummorfortegnelse 146 3. Sagn, folkesagn 147 4. Historier, anekdoter 148 5. Ordsprog, gåder, naturlyd 148 6. Formler, bønner, signelser, rim, remser 148 7. Viser Folkeviser 149 Alfabetisk titelfortegnelse 150 DgF-nummerfortegnelse 152 Folkelige viser 155 Varia 156 E. Sang, musik, dans, fremførelse 157 F. Leg, idræt, sport 157 V. Folkelivsforskning og etnologi 159 A. Etnologi i alm., teori, begreber, indsamling. - B. Bygnings kultur. - C. Dragt. - D. Husholdning, mad, drikke, nydelses midler. - E. Jordbrug, havebrug og skovbrug. - F. Røgt. - G. Fiskeri. - H. Håndværk og industri. Husflid. - I. Samfærdsel, transport, handel, markeder. - J. Samfund, organisation, rets pleje. - K. Lokalbeskrivelser, særlige erhvervs- og befolknings grupper. VI. Blandede historiske og kulturhistoriske emner 162 VII. Personregister 165 VIII. -

Elever Ved Kristiania Katedralskole Som Begynte På Skolen I Årene (Hefte 7)

1 Elever ved Kristiania katedralskole som begynte på skolen i årene (hefte 7). 1881 – 1890 Anders Langangen Oslo 2020 2 © Anders Langangen Hallagerbakken 82 b, 1256 Oslo (dette er hefte nr. 7 med registrering av elever ved Schola Osloensis). 1. Studenter fra Christiania katedralskole og noen elever som ikke fullførte skolen- 1611-1690. I samarbeid med Einar Aas og Gunnar Birkeland. Oslo 2018 2. Elever ved Christiania katedralskole og privat dimitterte elever fra Christiania 1691-1799. I samarbeid med Einar Aas & Gunnar Birkeland. Oslo 2017. 3. Studenter og elever ved Christiania katedralskole som har begynt på skolen i årene 1800 – 1822. Oslo 2018. 4. Studenter og elever ved Christiania katedralskole som begynte på skolen i årene 1823-1847. Oslo 2019. 5. Studenter og elever ved Christiania katedralskole som begynte på skolen i årene 1847-1870. Oslo 2019 6. Elever ved Kristiania katedralskole som begynte på skolen i årene 1871 – 1880. Oslo 2019. I dette syvende heftet følger rekkefølgen av elvene elevprotokollene. Det vi si at de er ordnet etter året de begynte på skolen på samme måte som i hefte 6. For hver elev er det opplysninger om fødselsår og fødselssted, foreldre og tidspunkt for start på skolen (disse opplysningene er i elevprotokollene). Dåpsopplysninger er ikke registrert her, hvis ikke spesielle omstendigheter har gjort det ønskelig (f.eks. hvis foreldre ikke er kjent eller uklart). I tillegg har jeg med videre utdannelse der hvor det vites. Også kort om karriere (bare hovedtrekk) etter skolen og når de døde. Både skolestipendiene og de private stipendiene er registrert, dessuten den delen av skolestipendiet som ble opplagt til senere utbetaling og om de ble utbetalt eller ikke. -

Hunnic Warfare in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries C.E.: Archery and the Collapse of the Western Roman Empire

HUNNIC WARFARE IN THE FOURTH AND FIFTH CENTURIES C.E.: ARCHERY AND THE COLLAPSE OF THE WESTERN ROMAN EMPIRE A Thesis Submitted to the Committee of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science. TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Laura E. Fyfe 2016 Anthropology M.A. Graduate Program January 2017 ABSTRACT Hunnic Warfare in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries C.E.: Archery and the Collapse of the Western Roman Empire Laura E. Fyfe The Huns are one of the most misunderstood and mythologized barbarian invaders encountered by the Roman Empire. They were described by their contemporaries as savage nomadic warriors with superior archery skills, and it is this image that has been written into the history of the fall of the Western Roman Empire and influenced studies of Late Antiquity through countless generations of scholarship. This study examines evidence of Hunnic archery, questions the acceptance and significance of the “Hunnic archer” image, and situates Hunnic archery within the context of the fall of the Western Roman Empire. To achieve a more accurate picture of the importance of archery in Hunnic warfare and society, this study undertakes a mortuary analysis of burial sites associated with the Huns in Europe, a tactical and logistical study of mounted archery and Late Roman and Hunnic military engagements, and an analysis of the primary and secondary literature. Keywords: Archer, Archery, Army, Arrow, Barbarian, Bow, Burial Assemblages, Byzantine, Collapse, Composite Bow, Frontier, Hun, Logistics, Migration Period, Roman, Roman Empire, Tactics, Weapons Graves ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. -

The Art of Staying Neutral the Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918

9 789053 568187 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 1 THE ART OF STAYING NEUTRAL abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 2 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 3 The Art of Staying Neutral The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918 Maartje M. Abbenhuis abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 4 Cover illustration: Dutch Border Patrols, © Spaarnestad Fotoarchief Cover design: Mesika Design, Hilversum Layout: PROgrafici, Goes isbn-10 90 5356 818 2 isbn-13 978 90 5356 8187 nur 689 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2006 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 5 Table of Contents List of Tables, Maps and Illustrations / 9 Acknowledgements / 11 Preface by Piet de Rooij / 13 Introduction: The War Knocked on Our Door, It Did Not Step Inside: / 17 The Netherlands and the Great War Chapter 1: A Nation Too Small to Commit Great Stupidities: / 23 The Netherlands and Neutrality The Allure of Neutrality / 26 The Cornerstone of Northwest Europe / 30 Dutch Neutrality During the Great War / 35 Chapter 2: A Pack of Lions: The Dutch Armed Forces / 39 Strategies for Defending of the Indefensible / 39 Having to Do One’s Duty: Conscription / 41 Not True Reserves? Landweer and Landstorm Troops / 43 Few -

Contrasting Portrayals of Women in WW1 British Propaganda

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2015 Vol. 13 of history, propaganda has been aimed at patriarchal Victims or Vital: Contrasting societies and thus, has primarily targeted men. This Portrayals of Women in WWI remained true throughout WWI, where propaganda came into its own as a form of public information and British Propaganda manipulation. However, women were always part of Stacey Reed those societies, and were an increasingly active part History 385 of the conversations about the war. They began to be Fall 2014 targeted by propagandists as well. In war, propaganda served a variety of More than any other war before it, World War I purposes: recruitment of soldiers, encouraging social invaded the every day life of citizens at home. It was the responsibility, advertising government agendas and first large-scale war that employed popular mass media programs, vilifying the enemy and arousing patriotism.5 in the transmission and distribution of information from Various governments throughout WWI found that the the front lines to the Home Front. It was also the first image of someone pointing out of a poster was a very to merit an organized propaganda effort targeted at the effective recruiting tool for soldiers. Posters presented general public by the government.1 The vast majority of British men with both the glory of war and the shame this propaganda was directed at an assumed masculine of shirkers. Women were often placed in the role of audience, but the female population engaged with the encouraging their men to go to war. Many propaganda messages as well. -

Raemaekers-EN-Cont-Intro.Pdf

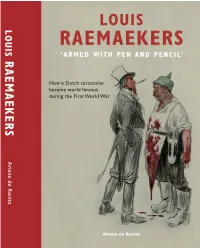

LOUIS RAEMAEKERS ‘ARMED WITH PEN AND PENCIL’ How a Dutch cartoonist became world famous during the First World War Ariane de Ranitz followed by the article ‘The Kaiser in Exile: Wilhelm II in Doorn’ Liesbeth Ruitenberg Louis Raemaekers Foundation 0.Voorwerk 1-21 Engels.indd 3 17-09-14 15:57 Table of Contents Preface and Acknowledgments 9 4 The war: anti-neutrality 75 Introduction 13 (1914–1915) Sources 16 The first weeks of the war 75 Rumours 75 1 Youth in Roermond 23 Belgian refugees 77 (1869–1886) War reporting 79 The Raemaekers family 23 Raemaekers’ response to the German invasion 82 Conflict between liberals and clericals 24 The attitude of the Dutch press 86 Roermond newspapers 26 Raemaekers and De Telegraaf 88 Joseph Raemaekers enters the fray 28 Violation of neutrality 88 De Volksvriend closes down 30 The attitude of De Telegraaf 90 Louis learns to draw 31 First album and exhibitions 93 Cultural life dominated by the firm of Cuypers 33 More publications 98 Neutrality in danger 100 2 Training and work as drawing teacher 35 A price on Raemaekers’ head? 103 (1887–1905) Schröder goes to jail 107 Drawing training in Nijmegen, Roermond More frequent cartoons; subjects and fame 108 and Amsterdam 35 First appointment as a drawing teacher 37 5 Raemaekers becomes famous abroad 115 Departure for Brussels 38 (1915–1916) Appointment in Wageningen 38 Distribution outside the Netherlands 115 Work as illustrator and portrait painter 44 International fame 121 Marriage and children 47 London 121 Children’s books 50 Exhibition at the Fine Art Society -

1 the Political Philosophy of Niccolò Machiavelli Filippo Del Lucchese Table of Contents Preface Part I

The Political Philosophy of Niccolò Machiavelli Filippo Del Lucchese Table of Contents Preface Part I: The Red Dawn of Modernity 1: The Storm Part II: A Political Philosophy 2: The philosopher 3: The Discourses on Livy 4: The Prince 5: History as Politics 6: War as an art Part III: Legacy, Reception, and Influence 7: Authority, conflict, and the origin of the State (sixteenth-eighteenth centuries) 1 8: Nationalism and class conflict (nineteenth-twentieth centuries) Chronology Notes References Index 2 Preface Novel 84 of the Novellino, the most important collection of short stories before Boccaccio’s Decameron, narrates the encounter between the condottiere Ezzelino III da Romano and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II: It is recorded how one day being with the Emperor on horseback with all their followers, the two of them made a challenge which had the finer sword. The Emperor drew his sword from its sheath, and it was magnificently ornamented with gold and precious stones. Then said Messer Azzolino: it is very fine, but mine is finer by far. And he drew it forth. Then six hundred knights who were with him all drew forth theirs. When the Emperor saw the swords, he said that Azzolino’s was the finer.1 In the harsh conflict opposing the Guelphs and Ghibellines – a conflict of utter importance for the late medieval and early modern history of Italy and Europe – the feudal lord Ezzelino sends the Emperor a clear message: honours, reputation, nobility, beauty, ultimately rest on force. Gold is not important, good soldiers are, because good soldiers will find gold, not the contrary. -

Leonardo Bruni, the Medici, and the Florentine Histories1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Queensland eSpace /HRQDUGR%UXQLWKH0HGLFLDQGWKH)ORUHQWLQH+LVWRULHV *DU\,DQ]LWL Journal of the History of Ideas, Volume 69, Number 1, January 2008, pp. 1-22 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI3HQQV\OYDQLD3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/jhi.2008.0009 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jhi/summary/v069/69.1ianziti.html Access provided by University of Queensland (30 Oct 2015 04:56 GMT) Leonardo Bruni, the Medici, and the Florentine Histories1 Gary Ianziti Leonardo Bruni’s relationship to the Medici regime raises some intriguing questions. Born in 1370, Bruni was Chancellor of Florence in 1434, when Cosimo de’ Medici and his adherents returned from exile, banished their opponents, and seized control of government.2 Bruni never made known his personal feelings about this sudden regime change. His memoirs and private correspondence are curiously silent on the issue.3 Yet it must have been a painful time for him. Among those banished by the Medici were many of his long-time friends and supporters: men like Palla di Nofri Strozzi, or Rinaldo degli Albizzi. Others, like the prominent humanist and anti-Medicean agita- tor Francesco Filelfo, would soon join the first wave of exiles.4 1 This study was completed in late 2006/early 2007, prior to the appearance of volume three of the Hankins edition and translation of Bruni’s History of the Florentine People (see footnote 19). References to books nine to twelve of the History are consequently based on the Santini edition, cited in footnote 52. -

Poetry and Society: Aspects of Shona, Old English and Old Norse Literature

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Poetry and Society: Aspects of Shona, Old English and Old Norse Literature Hazel Carter School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 4 One of the most interesting and stimulating the themes, and especially in the use made of developments of recent years in African studies certain poetic techniques common to both. has been the discovery and rescue of the tradi- Compare, for instance, the following extracts, tional poetry of the Shona peoples, as reported the first from the clan praises of the Zebra 1 in a previous issue of this journal. In particular, (Tembo), the second from Beowulf, the great to anyone acquainted with Old English (Anglo- Old English epic, composed probably in the Saxon) poetry, the reading of the Shona poetry seventh century. The Zebra praises are com- strikes familiar chords, notably in the case of plimentary and the description of the dragon the nheternbo and madetembedzo praise poetry. from Beowulf quite the reverse, but the expres- The resemblances are not so much in the sion and handling of the imagery is strikingly content of the poetry as in the treatment of similar: Zvaitwa, Chivara, It has been done, Striped One, Njunta yerenje. Hornless beast of the desert. Heko.ni vaTemho, Thanks, honoured Tembo, Mashongera, Adorned One, Chinakira-matondo, Bush-beautifier, yakashonga mikonde Savakadzu decked with bead-girdles like women, Mhuka inoti, kana yomhanya Beast which, when it runs amid the mumalombo, rocks, Kuatsika, unoona mwoto kuti cheru And steps on them, you see fire drawn cfreru.2 forth. -

Our Lady of Antwerp

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons Faculty Publications LSU Libraries 2018 Sacred vs. Profane in The Great War: A Neutral’s Indictment Marty Miller Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/libraries_pubs Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Marty, "Sacred vs. Profane in The Great War: A Neutral’s Indictment" (2018). Faculty Publications. 79. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/libraries_pubs/79 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the LSU Libraries at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sacred vs. Profane in The Great War: A Neutral’s Indictment Louis Raemaekers’s Use of Religious Imagery in Adoration of the Magi and Our Lady of Antwerp by Marty Miller Art and Design Librarian Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, Louisiana t the onset of the First World War in August 1914, Germany invaded France and Belgium, resulting in almost immediate British intervention and provoking a firestorm of protest throughout Western Europe. Belgium’s Asmall military was overmatched and reduced to fighting skirmishes as the Kaiser’s war machine headed toward France. Belgian civilians, as they had during the Franco- Prussian War, resisted by taking up arms. Snipers and ambushes slowed the Germans’ advance. In retaliation, German troops massacred Belgian men, women, and children. Cities, villages, and farms were burned and plundered.1 Belgian neutrality meant nothing to the German master plan to invade and defeat France before the Russian army could effectively mobilize in the east. -

GIANTS and GIANTESSES a Study in Norse Mythology and Belief by Lotte Motz - Hunter College, N.Y

GIANTS AND GIANTESSES A study in Norse mythology and belief by Lotte Motz - Hunter College, N.Y. The family of giants plays apart of great importance in North Germanic mythology, as this is presented in the 'Eddas'. The phy sical environment as weIl as the race of gods and men owe their existence ultimately to the giants, for the world was shaped from a giant's body and the gods, who in turn created men, had de scended from the mighty creatures. The energy and efforts of the ruling gods center on their battles with trolls and giants; yet even so the world will ultimately perish through the giants' kindling of a deadly blaze. In the narratives which are concerned with human heroes trolls and giants enter, shape, and direct, more than other superhuman forces, the life of the protagonist. The mountains, rivers, or valleys of Iceland and Scandinavia are often designated with a giant's name, and royal houses, famous heroes, as weIl as leading families among the Icelandic settlers trace their origin to a giant or a giantess. The significance of the race of giants further is affirmed by the recor ding and the presence of several hundred giant-names in the Ice landic texts. It is not surprising that students of Germanic mythology and religion have probed the nature of the superhuman family. Thus giants were considered to be the representatives of untamed na ture1, the forces of sterility and death, the destructive powers of 1. Wolfgang Golther, Handbuch der germanischen Mythologie, Leipzig 1895, quoted by R.Broderius, The Giant in Germanic Tradition, Diss. -

British Family Names

cs 25o/ £22, Cornrll IBniwwitg |fta*g BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrti W~ Sage 1891 A.+.xas.Q7- B^llll^_ DATE DUE ,•-? AUG 1 5 1944 !Hak 1 3 1^46 Dec? '47T Jan 5' 48 ft e Univeral, CS2501 .B23 " v Llb«"y Brit mii!Sm?nS,£& ori8'" and m 3 1924 olin 029 805 771 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029805771 BRITISH FAMILY NAMES. : BRITISH FAMILY NAMES ftbetr ©riain ano fIDeaning, Lists of Scandinavian, Frisian, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman Names. HENRY BARBER, M.D. (Clerk), "*• AUTHOR OF : ' FURNESS AND CARTMEL NOTES,' THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY OF MAULBRONN,' ( SOME QUEER NAMES,' ' THE SHRINE OF ST. BONIFACE AT FULDA,' 'POPULAR AMUSEMENTS IN GERMANY,' ETC. ' "What's in a name ? —Romeo and yuliet. ' I believe now, there is some secret power and virtue in a name.' Burton's Anatomy ofMelancholy. LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1894. 4136 CONTENTS. Preface - vii Books Consulted - ix Introduction i British Surnames - 3 nicknames 7 clan or tribal names 8 place-names - ii official names 12 trade names 12 christian names 1 foreign names 1 foundling names 1 Lists of Ancient Patronymics : old norse personal names 1 frisian personal and family names 3 names of persons entered in domesday book as HOLDING LANDS temp. KING ED. CONFR. 37 names of tenants in chief in domesday book 5 names of under-tenants of lands at the time of the domesday survey 56 Norman Names 66 Alphabetical List of British Surnames 78 Appendix 233 PREFACE.