Book Review Interpreting Cinema: Adaptations, Intertextualities, Art Movements by Jasbir Jain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Depiction of Real Life Misery Through the Lens of Hindi Film “ Dastak( (1970)”: an Analysis Neema Negi DSVV Uttrakahnd [email protected]

Everant.in/index.php/sshj Survey Report Social Science and Humanities Journal Depiction of Real life misery through the lens of Hindi Film “ Dastak( (1970)”: An Analysis Neema Negi DSVV Uttrakahnd [email protected] ABSTRACT ABSTRACT: Cinema is considered as the tool of social transformation, changing Corresponding Author: agent and the reflection of society. The different eras of Hindi Cinema Neema Negi illustrate the different concern of a common man and their struggle. The various themes represent the image of India with a different approach. Social issues in the earlier eras were the dominant one theme on poverty , unemployment, problem of urban spaces, exploitation of peasants ,corruption, nation and nationalism were the main subject and each storytellers represent those emotions and problems in an ideal way .The present paper analyse the social issues and struggle of a common man and moreover how the director execute the human drama the agony faced by an ordinary people who live in the metropolis and their aspirations of life with the use of metaphors.. Keywords: social issues, metaphors, urban space I- Thematic trends of Hindi Cinema Hindi Cinema deals with diverse themes from last magnificent 100 years . Variety of socially relevant issues cultural issues are addressed by combining them with a fantasies, tradition and myths. Hindi film can be used to know the history of society and culture of India . Indian Cinema has been reflecting social, political and economic dynamics of the national community in it’s narrative since the beginning of the 20th century. The themes such as globalization nation and nationalism, caste, class, gender, terrorism and social issues themes but also suggest cinematic interpretation to solve the problems. -

A . LTHE F'xl.R-1 XNDTJSTFIYXNXNOXA . Auivro

Pix STOR-X 0-A.L E=>E:RS F'EOTX'VAE: OP** THE F'XL.r-1 XNDTJSTFIY X N XNOXA. AuIvrO ABF^OJOILD 3.1 Evolution of Film Industry in the Western Countries: Decline of feudal society that accompanied the Industrial Revolution had created a vacuum in the social and cultural life of man in the Western society. However, the parallel revolution in the field of communications could fill this vacuum by introducing the mass media like films. "• Unlike the telephone, telegraph or even wireless, the invention of film can not be attributed to any single inventor. It depended upon a whole series of small inventions by different inventors. In the U.S.A, Thomas Edison invented what he called 'Kinetoscope'.= In England, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson was the chief experimenter who demonstrated a crude system of projection as early as in 1889. The Kinetoscope inspired a number of European and American inventors to apply their talents to further improve the technique of making and projecting a film. The solution to the important problem of projecting a film for a large audience was not saught by Edison. To him, his Kinetoscope was a Peep-Show box for individual viewing. However, Lumiere Brothers in France introduced their cinematographic machine and arranged the first public show of a film on a cold 34 December night in 1895. •= This show held at the Grand Cafe m Pans was followed by similar shows all over the world including India. Economically, the Cinematographe of Lumiere which could make projection possible for large audience had far reaching implications. -

The Hindu, the Muslim, and the Border In

THE HINDU, THE MUSLIM, AND THE BORDER IN NATIONALIST SOUTH ASIAN CINEMA Vinay Lal University of California, Los Angeles Abstract There is but no question that we can speak about the emergence of the (usually Pakistani or Muslim) ‘terrorist’ figure in many Bollywood films, and likewise there is the indisputable fact of the rise of Hindu nationalism in the political and public sphere. Indian cinema, however, may also be viewed in the backdrop of political developments in Pakistan, where the project of Islamicization can be dated to least the late 1970s and where the turn to a Wahhabi-inspired version of Islam is unmistakable. I argue that the recent history of Pa- kistan must be seen as instigated by a disavowal of the country’s Indic self, and similarly I suggest that scholarly and popular studies of the ‘representation’ of the Muslim in “Bol- lywood” rather too easily assume that such a figure is always the product of caricature and stereotyping. But the border between Pakistan and India, between the self and the other, and the Hindu and the Muslim is rather more porous than we have imagined, and I close with hints at what it means to both retain and subvert the border. Keywords: Border, Communalism, Indian cinema, Nationalism, Pakistan, Partition, Veer-Zaara Resumen 103 Así como el personaje del ‘terrorista’ (generalmente musulmán o paquistaní) está presente en muchos filmes de Bollywood, el nacionalismo hindú está tomando la iniciativa en la esfera política del país. Sin embargo el cine indio también puede hacerse eco de acontecimientos ocurridos en Paquistán, donde desde los años Setenta se ha manifestado un proceso de islamización de la sociedad, con una indudable impronta wahabí. -

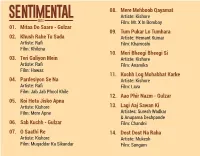

Sentimental Booklet for Web Copy

08. Mere Mehboob Qayamat Artiste: Kishore Film: Mr. X In Bombay 01. Mitaa Do Saare - Gulzar 09. Tum Pukar Lo Tumhara 02. Khush Rahe Tu Sada Artiste: Hemant Kumar Artiste: Rafi Film: Khamoshi Film: Khilona 10. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si 03. Teri Galiyon Mein Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Rafi Film: Anamika Film: Hawas 11. Kuchh Log Mohabbat Karke 04. Pardesiyon Se Na Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Rafi Film: Lava Film: Jab Jab Phool Khile 12. Aao Phir Nazm - Gulzar 05. Koi Hota Jisko Apna Artiste: Kishore 13. Lagi Aaj Sawan Ki Film: Mere Apne Artistes: Suresh Wadkar & Anupama Deshpande 06. Sab Kuchh - Gulzar Film: Chandni 07. O Saathi Re 14. Dost Dost Na Raha Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Mukesh Film: Muqaddar Ka Sikandar Film: Sangam 2 3 15. Hui Sham Unka Khayal 22. Din Dhal Jaye Haye Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Mere Hamdam Mere Dost Film: Guide 01. Mitaa Do Saare - Gulzar 16. Kuchh To Log Kahenge 23. Mere Toote Huye Dil Se 02. Khush Rahe Tu Sada Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Rafi Film: Amar Prem Film: Chhalia Film: Khilona 17. Waqt Karta Jo Wafa 24. Hue Hum Jinke Liye 03. Teri Galiyon Mein Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Dil Ne Pukara Film: Deedar Film: Hawas 18. Patthar Ke Sanam 25. Koi Sagar Dil Ko Bahlata 04. Pardesiyon Se Na Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Patthar Ke Sanam Film: Dil Diya Dard Liya Film: Jab Jab Phool Khile 19. Khilona Jan Kar Tum To 26. Chandi Ki Deewar 05. Koi Hota Jisko Apna Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Kishore Film: Khilona Film: Vishwas Film: Mere Apne 20. -

Smita Patil: Fiercely Feminine

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Smita Patil: Fiercely Feminine Lakshmi Ramanathan The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2227 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE BY LAKSHMI RAMANATHAN A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 i © 2017 LAKSHMI RAMANATHAN All Rights Reserved ii SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE by Lakshmi Ramanathan This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts. _________________ ____________________________ Date Giancarlo Lombardi Thesis Advisor __________________ _____________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Acting Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE by Lakshmi Ramanathan Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi Smita Patil is an Indian actress who worked in films for a twelve year period between 1974 and 1986, during which time she established herself as one of the powerhouses of the Parallel Cinema movement in the country. She was discovered by none other than Shyam Benegal, a pioneering film-maker himself. She started with a supporting role in Nishant, and never looked back, growing into her own from one remarkable performance to the next. -

![India of My Dreams [Towards Sustainability] © 2020 IJSR Received: 28-03-2020 Shivangi Sharma](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7106/india-of-my-dreams-towards-sustainability-%C2%A9-2020-ijsr-received-28-03-2020-shivangi-sharma-1247106.webp)

India of My Dreams [Towards Sustainability] © 2020 IJSR Received: 28-03-2020 Shivangi Sharma

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2020; 6(3): 105-107 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2020; 6(3): 105-107 India of my dreams [Towards sustainability] © 2020 IJSR www.anantaajournal.com Received: 28-03-2020 Shivangi Sharma Accepted: 30-04-2020 Shivangi Sharma Abstract Research Scholar From Delhi The present study entitled “India of My Dreams, Towards Sustainability” is based upon a picture of a University, New Delhi, India Vedic sustainable life. My main objective is to take India towards the same Vedic essence where we treated the earth, cow and the ganga as our mother, where AUM is the root cause of all the meditations, where the sustenance is based upon agriculture, where yagya performed to purify the air and where there is no technology but still they were prosperous and happy. Vedic life is full of sustainability, by the praises of the earth, sun, moon, varuna, Indra, vanaspati they are giving the inspiration to worship and protect them- यथा सूययश्च चन्द्रश्च न विभीतो न विभीतो न रिष्यतः एिा मे प्राण मा विभे।1 That is May we all do our work just like the sun and the moon without any fear. Also we follow the path of welfare similarly as the sun and the moon2 For them nature was the only key to success. And this kind of sustainability is India’s biggest need today. If we are trying to reduce the pollution, beat climate change and dealing other environment problems we should keep this in our mind that vedic lifestyle is the only solution. -

Rajinder Singh Bedi (Bio for Centennial Celebrations)

© Nischint Bhatnagar Rajinder Singh Bedi (Bio for Centennial celebrations) Born September 01, 1915 at Lahore Cantonment, Sadar Bazaar; Died November 11, 1984 in Bombay. His father, S. Hira Singh Bedi was a Postmaster. He was very fond of Urdu and Farsi. His Mother Smt. Sewa Dei was from a Hindu family and very knowledgeable of Sikh and Hindu religion, the stories of the Puranas and also of Muslim lore. She was a wonderful painter and had covered the walls of the house with scenes from the Mahabharata. The house had a mixed culture of Sikhism and Hinduism and father took part in Muslim festivals enthusiastically. Rajinder’s imaginative skills were developed under their fond care, storytelling and father’s witticisms. He matriculated from the S.B.B.S. Khalsa High School, Lahore and joined the DAV College, Lahore. He passed his Intermediate but could not go for BA studies. Mother had died March 28, 1933 of tuberculosis and father wanted him to marry so that there may be a caregiver in the family. He left his studies and joined the postal service as a clerk in 1933. He got married in 1934. His wife’s maiden name was Soman and married name Satwant Kaur. His first son, Prem, was born in 1935. Father who was then working as Postmaster in Toba Tek Singh came to Lahore to celebrate the arrival of a grandson but died there on August 31, 1935. The whole burden for fending for his family, his two brothers and sister fell on him and Satwant. The son Prem also passed away in 1936. -

Gurpurab Greetings

www.punjabadvanceonline.com Gurpurab Greetings Sri Guru Nanak Dev's 550th birth anniversary (Nov 23) 2 Punjab Advance August 2016 Editorial The Boy Who Cried Wolf is one of my favourite Aesop's Fables, I don’t know why but it appears to fit into the current Delhi smog tale. For the third year running Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal repeated his ‘stubble burning’ cries. His hat-trick of alarm calls remind me of the shepherd boy who cried wolf, with no wolf around. Initially the people came to his aid, but when he repeated the cries no one turned up and ultimately he fell vic - tim to his own follies. The Punjab Chief Minister Capt Amarinder Singh has been quick in ridi - culing the nonsensical claim of his Delhi counterpart asking him to stop in - dulging in political theatrics and to check the facts before shooting from the mouth. He has trashed as yet another attempt by the Delhi Chief Min - ister to divert public attention for his own government’s abysmal failure on all counts. As per data provided by private and government agencies stubble burn - ing accounts for a bare 4 per cent of the total smog enveloping the National Capital Region. More than 80 per cent of the deadly cocktail of soot, smoke, metals, nitratres, sulphates is the result of the local activities like vehicu - lar traffic, industrial pollution, construction activity, garbage burning etc. Vehicular pollution alone contributes 40 per cent of the total pollution level. According to the latest data released by the Ministry of Earth Sciences and the Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) crop burning, which lasts for about 15-20 days during this period, contributes just 4 per cent of the total pollution in Delhi-NCR on an average. -

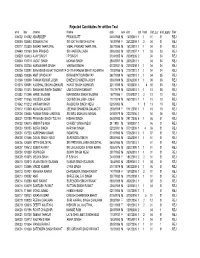

Rejected List for Written Examination for Assistant Accountant

Rejected Candidates for written Test slno bar cname fname dob sex dor cat hcat dist_p_r dist_apply filler 000002 101382 AMARDEEP PRANI DUTT 04061988 M 13092010 1 1 01 01 REJ 000039 102683 SONIA KUTHI SRI SATYA SINGH KUTHI 16031989 F 26122009 1 2 04 01 REJ 000117 103320 SAGAR THAPLIYAL VIMAL PRASAD THAPLIYAL 26071985 M 16122010 1 1 04 01 REJ 000440 102160 SHIV PRASAD SRI HARI BALLABH 30061983 M 03122007 1 1 03 03 REJ 000539 103433 AJAY SINGH I P SINGH 01041985 M 20092008 2 04 04 REJ 000540 103710 JAGAT SINGH MOHAN SINGH 28061987 M 25052010 1 04 04 REJ 000576 103255 KARMAVEER SINGH VIKRAM SINGH 01031981 M 23102009 1 1 04 04 REJ 000706 103291 SHIVASHISH BHATTACHARYA CHITTARANJAN BHATTACHARYA 10031985 M 27072010 1 1 04 04 REJ 000865 103086 AMIT UPADHYAY BRIHASPATI UPADHYAY 06071989 M 16022010 1 1 04 05 REJ 001168 108598 PAWAN KUMAR JOSHI DINESH CHANDRA JOSHI 30061989 M 20062008 1 1 08 08 REJ 001215 108591 KAUSHAL SINGH ADHIKARI HAYAT SINGH ADHIKARI 22111989 M 15032008 1 6 08 08 REJ 001235 110474 SHANKAR SINGH SAMANT UMED SINGH SAMANT 11011979 M 03052010 1 1 10 08 REJ 001352 110298 HANSI SAJWAN MAHENDRA SINGH SAJWAN 16071986 F 01092007 1 2 10 10 REJ 001427 110065 YOGESH JOSHI GOVIND BALLABH JOSHI 11011979 M 06072010 1 1 10 10 REJ 001542 110212 VIKRAM SINGH RAJENDRA SINGH NEGI 02051983 M 1 3 13 10 REJ 001612 110360 ALKA DALAKOTI JEEWAN CHANDRA DALAKOTI 25061989 F 01112008 1 1 10 10 REJ 002006 105655 PAWAN SINGH LINGWAL SRI BRIJ MOHAN LINGWAL 04061979 M 23022005 1 04 05 REJ 050001 102159 PRAKASH SINGH TOLIYA KISHAN SINGH 04051980 M 29112005 -

Punjab Medical Council Electoral Rolls Upto 31-01-2018

Punjab Medical Council Electoral Rolls upto 31-01-2018 S.No. Name/ Father Name Qualification Address Date of Registration Validity Registration Number 1. Dr. Yash Pal Bhandari S/o L.M.S.F. 1948 81, Vijay Nagar, Jalandhar 12.04.1948 45 22.10.2018 Sh. Ram Krishan M.B.B.S. 1961 M.D. 1965 2. Dr. Balwant Singh S/o LSMF 1952 1814, Maharaj nagar, Near Gate No.3, 28.10.1952 3266 17.03.2021 Sh. Suhawa Singh M.B.B.S. 1964 of P.A.U., Ludhiana 3. Dr. Kanwal Kishore Arora S/o M.B.B.S. 1952 392, Adarsh Nagar Jalandhar 15.12.1952 3312 09.03.2019 Sh. Lal Chand Pasricha 4. Dr. Gurbax Singh S/o LSMF 1952 B-5/442, Kulam Road, Tehsil 11.03.1953 3396 23.04.2019 Sh. Mangal Singh M.B.B.S. 1956 Nawanshahr Distt. SBS Nagar D.O. 1957 5. Dr. Jawahar Lal Luthra L.S.M.F. 1953 H.No.44, Sector 11-A, Chandigarh 27.10.1953 3555 07.10.2018 M.B.B.S. 1956 M.S. (Ophth.) 1970 6. Dr. Kirpal Kaur M.B.B.S. 1953 490, Basant Avenue, Amritsar 09.12.1953 3599 31.03.2019 M.D. 1959 7. Dr. Harbans Kaur Saini L.S.M.F. 1954 Railway Road, Nawan Shahr Doaba 31.05.55 4092 29.01.2019 8. Dr. Baldev Raj Bhateja L.S.M.F. 1955 Raj Poly Clinic and Nursing Home, Pt. 08-06-1955 4106 09.10.2018 Jai Dayal St., Muktsar. -

Été Indien 10E Édition 100 Ans De Cinéma Indien

Été indien 10e édition 100 ans de cinéma indien Été indien 10e édition 100 ans de cinéma indien 9 Les films 49 Les réalisateurs 10 Harishchandrachi Factory de Paresh Mokashi 50 K. Asif 11 Raja Harishchandra de D.G. Phalke 51 Shyam Benegal 12 Saint Tukaram de V. Damle et S. Fathelal 56 Sanjay Leela Bhansali 14 Mother India de Mehboob Khan 57 Vishnupant Govind Damle 16 D.G. Phalke, le premier cinéaste indien de Satish Bahadur 58 Kalipada Das 17 Kaliya Mardan de D.G. Phalke 58 Satish Bahadur 18 Jamai Babu de Kalipada Das 59 Guru Dutt 19 Le vagabond (Awaara) de Raj Kapoor 60 Ritwik Ghatak 20 Mughal-e-Azam de K. Asif 61 Adoor Gopalakrishnan 21 Aar ar paar (D’un côté et de l’autre) de Guru Dutt 62 Ashutosh Gowariker 22 Chaudhvin ka chand de Mohammed Sadiq 63 Rajkumar Hirani 23 La Trilogie d’Apu de Satyajit Ray 64 Raj Kapoor 24 La complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) de Satyajit Ray 65 Aamir Khan 25 L’invaincu (Aparajito) de Satyajit Ray 66 Mehboob Khan 26 Le monde d’Apu (Apur sansar) de Satyajit Ray 67 Paresh Mokashi 28 La rivière Titash de Ritwik Ghatak 68 D.G. Phalke 29 The making of the Mahatma de Shyam Benegal 69 Mani Ratnam 30 Mi-bémol de Ritwik Ghatak 70 Satyajit Ray 31 Un jour comme les autres (Ek din pratidin) de Mrinal Sen 71 Aparna Sen 32 Sholay de Ramesh Sippy 72 Mrinal Sen 33 Des étoiles sur la terre (Taare zameen par) d’Aamir Khan 73 Ramesh Sippy 34 Lagaan d’Ashutosh Gowariker 36 Sati d’Aparna Sen 75 Les éditions précédentes 38 Face-à-face (Mukhamukham) d’Adoor Gopalakrishnan 39 3 idiots de Rajkumar Hirani 40 Symphonie silencieuse (Mouna ragam) de Mani Ratnam 41 Devdas de Sanjay Leela Bhansali 42 Mammo de Shyam Benegal 43 Zubeidaa de Shyam Benegal 44 Well Done Abba! de Shyam Benegal 45 Le rôle (Bhumika) de Shyam Benegal 1 ] Je suis ravi d’apprendre que l’Auditorium du musée Guimet organise pour la dixième année consécutive le festival de films Été indien, consacré exclusivement au cinéma de l’Inde.