Beyond Nuts and Bolts: How Organisational Factors Influence the Implementation of Environmental Technology Projects in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRONDHEIMSREGIONEN – En Arena for Samarbeid

TRONDHEIMSREGIONEN – en arena for samarbeid Bård Eidet, daglig leder Trondheimsregionen Hvorfor regionalt samarbeid? • For å løse oppgaver bedre og mer effektivt enn den enkelte kommune kan gjøre? • For å gi større kraft til felles interesser? • Fordi det er oppgaver som finner sine beste løsninger mellom en kommune og et fylkesnivå? Grunnleggende: Det må finnes en vilje til å samarbeide, og en felles forståelse av at fellesskapet tjener på det samlet sett …men hvorfor Trondheimsregionen? • Ole Eirik Almlid (adm.dir. i NHO) ved lanseringen av kommunebarometeret: • “Almlid mener målingen viser hvilke kommuner som kan oppleves som de mest attraktive for næringslivet. Han mener målingen viser at kommuner som ligger i randsonen til de store kommunene, og som definerer seg inn i storbyregionen framfor å vende blikket mot distriktskommuner i stedet, har en tendens til å score bra.” • Hva gjør Trondheimsregionen? Et samarbeid mellom 10 – nei 9 – nei 8 kommuner – politisk styrt Indre 4 programområder: Fosen Strategisk næringsutvikling Nye Interkommunal arealplan Profilering/kommunikasjon/attraktiv region Ledelse/samarbeid/interessepolitikk Ikke fokus på tjenesteproduksjon Det politiske organet . Åtte kommuner, fylkeskommunen som observatør Stjørdal, Malvik, Trondheim, Melhus, Midtre Gauldal, Orkdal, Skaun, Indre Fosen Styrke Trondheimsregionens utvikling i en nasjonal og internasjonal • konkurransesituasjon. Politiske hovedmål Strategisk næringsplan (SNP): * Øke BNP slik at den tilsvarer vår andel av befolkningen i 2020 * Doble antall teknologibedrifter og -arbeidsplasser innen 2025 Interkommunal arealplan (IKAP): * Klimavennlig arealbruk og transport * Boligbygging nær sentra og kollektivtilbud * Jordvern * Fordele veksten . Politisk idé * Vi oppnår mer sammen enn hver for oss Organisasjon Trondheimsregionen – regionrådet RR Trondheim kommune (ordfører, opposisjon, rådmann) vertskommune Arbeidsutvalget – AU Daglig leder (leder, nestleder + 2 ordførere) Prosjektleder Næringsrådet - NF med sekretariat for (2 FoU, 3 næringsliv, 3 næringsplanen. -

Nye Fylkes- Og Kommunenummer - Trøndelag Fylke Stortinget Vedtok 8

Ifølge liste Deres ref Vår ref Dato 15/782-50 30.09.2016 Nye fylkes- og kommunenummer - Trøndelag fylke Stortinget vedtok 8. juni 2016 sammenslåing av Nord-Trøndelag fylke og Sør-Trøndelag fylke til Trøndelag fylke fra 1. januar 2018. Vedtaket ble fattet ved behandling av Prop. 130 LS (2015-2016) om sammenslåing av Nord-Trøndelag og Sør-Trøndelag fylker til Trøndelag fylke og endring i lov om forandring av rikets inddelingsnavn, jf. Innst. 360 S (2015-2016). Sammenslåing av fylker gjør det nødvendig å endre kommunenummer i det nye fylket, da de to første sifrene i et kommunenummer viser til fylke. Statistisk sentralbyrå (SSB) har foreslått nytt fylkesnummer for Trøndelag og nye kommunenummer for kommunene i Trøndelag som følge av fylkessammenslåingen. SSB ble bedt om å legge opp til en trygg og fremtidsrettet organisering av fylkesnummer og kommunenummer, samt å se hen til det pågående arbeidet med å legge til rette for om lag ti regioner. I dag ble det i statsråd fastsatt forskrift om nærmere regler ved sammenslåing av Nord- Trøndelag fylke og Sør-Trøndelag fylke til Trøndelag fylke. Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet fastsetter samtidig at Trøndelag fylke får fylkesnummer 50. Det er tidligere vedtatt sammenslåing av Rissa og Leksvik kommuner til Indre Fosen fra 1. januar 2018. Departementet fastsetter i tråd med forslag fra SSB at Indre Fosen får kommunenummer 5054. For de øvrige kommunene i nye Trøndelag fastslår departementet, i tråd med forslaget fra SSB, følgende nye kommunenummer: Postadresse Kontoradresse Telefon* Kommunalavdelingen Saksbehandler Postboks 8112 Dep Akersg. 59 22 24 90 90 Stein Ove Pettersen NO-0032 Oslo Org no. -

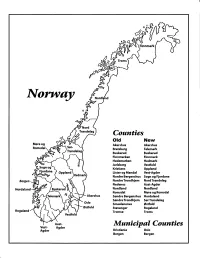

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Faglig Og Økonomisk Evaluering Av Helse Og Velferd

Faglig og økonomisk evaluering av Helse og velferd Levanger kommune www.pwc.com 9.12.2020 PwC | Faglig og økonomisk evaluering av Helse og velferd | Levanger kommune 1 Innhold 1 Sammendrag 2 Kapittel 1 - Bakgrunn, mandat og metode 3 Kapittel 2 - Status og trender for Helse og velferd i Levanger kommune 4 Kapittel 3 - Årsaker til økonomiske utfordringer i helse og velferd 5 Kapittel 4 - Innsparingstiltak 6 Kapittel 5 - Anbefalinger 7 Vedlegg PwC | Faglig og økonomisk evaluering av Helse og velferd | Levanger kommune 2 2 Ansvarsbegrensning Denne rapporten er utarbeidet for Levanger kommunes interne bruk i samsvar med engasjementsbrevet datert 11.08.2020. Våre vurderinger bygger på faktainformasjon som har fremkommet i møter med Levanger kommunes ledere og i dokumentasjon som Levanger kommune har gjort tilgjengelig for oss. PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) har ikke foretatt noen selvstendig verifisering av informasjonen som har fremkommet, og vi innestår ikke for at den er fullstendig, korrekt og presis. PwC har ikke utført noen form for revisjon eller kontrollhandlinger av Levanger kommunes virksomhet. Levanger kommune har rett til å benytte informasjonen i denne rapporten i sin virksomhet, i samsvar med forretningsvilkårene som er vedlagt vårt engasjementsbrev. Rapporten og/eller informasjon fra rapporten skal ikke benyttes for andre formål eller distribueres til andre uten skriftlig samtykke fra PwC. PwC påtar seg ikke noe ansvar for tap som er lidt av Levanger kommune eller andre som følge av at vår rapport eller utkast til rapport er distribuert, gjengitt eller på annen måte benyttet i strid med disse bestemmelsene eller engasjementsbrevet. PwC beholder opphavsrett og alle andre immaterielle rettigheter til rapporten samt ideer, konsepter, modeller, informasjon og know-how som er utviklet i forbindelse med vårt arbeid. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Tydal, Selbu, Meråker, Frosta, Malvik Og Stjørdal

Forslag, 18. mars 2016 Intensjonsavtale for etablering av Værnes kommune for kommunene Tydal, Selbu, Meråker, Frosta, Malvik og Stjørdal Intensjonsavtalen bygger på «Grunnlagsdokumentet for en intensjonsavtale for etablering av VÆRNES kommune, 24. februar 2016» 1 1 Kommunene i Værnesregionen Stjørdal er vekstsenteret i regionen med sin sentrale beliggenhet i forhold til Trondheim, Værnes flyplass og kommunikasjonslinjene E-6, E-14 og jernbanen. Stjørdal vil være det naturlige sentrum i en ny Værnes kommune. Behovet for å sikre bærekraftig vekst er viktig for hele regionen og tilsier at det må fokuseres på vekst i tettstedene og i omlandet, i tillegg til i byen og kommunesenteret Stjørdal. Samlet befolkning i en ny kommune bestående av alle kommunene(6) i dagens Værnesregion var pr 31.12.15 på 47 165 innbyggere. Forslag til intensjonsavtale – Værnes kommune 2 2 Mål, avklaringer og hovedoppgaver for den nye kommunen 2.1 Generell målsetting Sammenslåingen skal gi en verdiskapende kommune som skal utnytte styrkene i de ulike tettstedene der alle jobber sammen for å utvikle attraktive og gode lokalsamfunn, med fremtidsrettede tjenester til det beste for den enkelte innbygger, hyttefolk, besøkende og næringsliv. 2.2 Avklaringer 2.2.1 Navnet på den nye kommunen Ettersom kommunene har jobbet meget godt sammen i Værnesregionen og lyktes med dette, er det naturlig å forslå at navnet Værnes videreføres i kommunenavnet. Værnesregionen er blitt kjent for sin evne til samarbeid og har høstet gode tilbakemeldinger både lokalt, regionalt og nasjonalt. Navnet Værnes, i kommunesammenheng, har allerede et godt omdømme som det bør bygges videre på. Av disse grunner er det naturlig å velge Værnes som navn på den nye kommunen. -

Bakgrunnsstatistikk

Bakgrunnsstatistikk Vedlegg til tilrådning kommunestruktur i Sør-Trøndelag 30.09.2016 Folk og samfunn Barnehage og Barn og foreldre Helse og omsorg Miljø og klima Landbruk, mat og Kommunal styring Plan og bygg Samfunnssikkerhet og opplæring reindrift beredskap Befolkningsutvikling 1992-2040 Osen 60 4 Roan 50 Åfjord 3 Befolkningsutvikling Bjugn i prosent 2016-2040 40 Frøya Ørland -9 - 0 % 2 Rissa 1 - 15 % Hitra 30 16 - 25 % Agdenes 1 26 - 50 % Snillfjord Trondheim 20 Malvik Hemne Orkdal Skaun 0 Klæbu 10 Melhus Selbu PROSENT (LINJE) PROSENT PROSENT (STOLPE) PROSENT -1 Meldal 0 Tydal Midtre Gauldal -2 Rennebu Holtålen -10 -3 -20 Oppdal Røros -30 -4 Befolkningsendring i prosent 1992-2016 Befolkningsframskriving i prosent 2016-2040 (MMMM-alternativet 2016) Befolkningsendring i prosent 2015-2016 BEFOLKNING Innbyggere Befolkningsfordeling < - 3.200 5 - 265 3.200 - 9.000 266 - 956 9.000 - 20.000 957 - 2340 20.000 - < 2341 - 5130 Kilde: SSB Dagens bo- og arbeidsmarked Kilde: NIBR 2013:1 Utvikling eldre fram til 2040 2016 2020 2040 2016-2040 Osen Prognose Personer 80 Personer 80 Personer 80 utvikling Roan Kommune år og eldre år og eldre år og eldre 2014 til 2040 Klæbu 137 168 448 227 % Malvik 379 453 1113 194 % Åfjord Prognose utvikling Skaun 264 273 639 142 % 2014 til 2040 Holtålen 107 135 240 124 % Bjugn Frøya 24 - 50 Trondheim 6552 6718 14635 123 % Ørland Orkdal 558 567 1213 117 % Rissa 51 - 80 Bjugn 247 272 521 111 % 81 - 100 Hitra Melhus 650 678 1360 109 % Agdenes 101 - 227 Oppdal 361 376 735 104 % Snillfjord Hitra 228 246 462 103 % Trondheim -

Vedlegg 3: Forslag Til Strategi for Anbud Buss Trøndelag Region 2021

Vedlegg 3: Forslag til strategi for Anbud buss Trøndelag region 2021 (Regionanbud 2021) Vedlegg 3 – Utvikling i Trøndelags kommuner Endelig leveranse AtB AS Forslag til strategi for Anbud buss Trøndelag region 2021 Vedlegg 3 – Utvikling i Trøndelags kommuner Dato: 2018-07-02 1 DOKUMENTINFORMASJON Oppdragsgiver: Trøndelag fylkeskommune Grunnlag Mandat for anbud på kollektivtrafikk i Trøndelag utenom Stor-Trondheim fra 2021. Vedtatt i Fylkestinget den 28.2.2018. Rapportnavn: Forslag til strategi for Anbud buss Trøndelag region 2021 (Regionanbud 2021) Vedlegg 3 – Utvikling i Trøndelags kommuner Arkivreferanse: Klikk her for å skrive inn tekst. Oppdrag: Prosjektbeskrivelse: Prosjekteier: Janne Sollie Fag: Kollektivtrafikk Tema Anbudsstrategi Leveranse: Rapport til Trøndelag fylkeskommune den xx. oktober 2018 Skrevet av: AtB AS Kvalitetskontroll: AtB AS 2 FORORD Astrid 3 SAMMENDRAG … 4 Innholdsfortegnelse 1 Regioner i Trøndelag ____________________________________________________________ 7 2 Befolkning og utvikling i Trøndelag _________________________________________________ 9 Befolkningsutvikling _________________________________________________________ 9 Arbeids- og studieplasser ____________________________________________________ 11 Arbeidspendling ___________________________________________________________ 11 3 Befolkning og utvikling Namdalsregionen ___________________________________________ 14 Befolkningsutvikling ________________________________________________________ 14 Aldersutvikling ____________________________________________________________ -

Informasjonsbrosjyre Om Hjortevilt I Malvik Kommune Side 2

1 Organisering i Malvik - hjorteviltjakt I Malvik kommune er det i 2018 5 vald for jakt på elg. To områder forvaltes etter en godkjent bestandsplan. I disse områdene blir det også gitt fellingstillatelser for hjort. Tre mindre vald får tildelt dyr ut fra tellende areal. Jaktfeltene Midtre og Nedre indre for Malvik grunneierlag er slått sammen til et jaktfelt (jaktfelt 2), Øvre indre (jaktfelt 1), ytre (jaktfelt 3) og statsallmenningen (jaktfelt 4). Det er i 2018 registrert 8 vald for rådyrjakt i kommunen. Årlig felles det ca. 80-90 elg og ca. 30-40 rådyr. Det ble ikke felt hjort i 2017. 2 Skrantesjuke (CWD)-undersøkelser i 2018 Det vil også i 2018 bli samlet inn prøver fra hjortevilt på grunn av skrantesjuke. Miljødirektoratet har gitt pålegg om prøvetaking. Prøver tas fra elg og hjort som er 2 år og eldre. Det skal tas hjerneprøve og lymfeprøve. Kjever skal leveres fra alle dyr (også kalv). Dyr som er 2 år og eldre vil bli nøyaktig aldersbestemt av NINA. Første innsamling av kjever er mandag 29.10. Det er ikke pålegg om å ta prøver av rådyr. Valdene har fått «jegerpakker» med utstyr. Jegerne tar prøvene selv og sender inn. Informasjonsbrosjyre om hjortevilt i Malvik kommune side 2 I tillegg samles det prøver fra alt fallvilt av hjortevilt som er 1 år og eldre. 1. Registrer fortløpende felte og sette dyr i www.settogskutt.no 2. Hold oversikt over merkelapper og innsenders nummer 3. Legg inn slaktevekter og cwd-prøver 4. Lever cwd-prøve selv (jegerpakker) 5. Vent med levering av prøven til mandag hvis dyr skytes fredag-søndag 6. -

Kjøp Av Landbaserte Pasientreiser I Sør-Trøndelag Fylke Utenom Trondheim, Malvik, Rissa, Selbu Og Tydal

Kjøp av landbaserte pasientreiser i Sør-Trøndelag fylke utenom Trondheim, Malvik, Rissa, Selbu og Tydal Kjøp av landbaserte pasientreiser i Sør- Trøndelag fylke utenom Trondheim, Malvik, Rissa, Selbu og Tydal Revised 8/22/2017 10:02:56 PM Kjøp av landbaserte pasientreiser i Sør-Trøndelag fylke utenom Trondheim, Malvik, Rissa, Selbu og Tydal Table of contents 1 Innledning 1.1 Oppdragsgiver 1.2 Helse Midt-Norge RHF 2 Anskaffelsen 2.1 Formål - Omfang av oppdraget 2.2 Anbudsområder omfattet av konkurransen 2.3 Estimert økonomisk omfang 2.4 Kontraktsperiode 3 Konkurransebestemmelser 3.1 Generelt 3.2 Kommunikasjon 3.3 Tilbud 3.4 Minste tilbud 3.5 Tilbud som omfatter flere anbudsområder 3.6 Pris 3.7 Maksimalpris 3.8 Tilbudskonferanse 3.9 Kostnader 3.10 Offentlighet 4 Kvalifikasjonskrav/ESPD skjema 4.1 Kvalifikasjonskrav 4.2 ESPD skjema 5 Tilbudet 6 Evaluering og tildeling 6.1 Tildelingskriterie Revised 8/22/2017 10:02:56 PM Kjøp av landbaserte pasientreiser i Sør-Trøndelag fylke utenom Trondheim, Malvik, Rissa, Selbu og Tydal 1 Innledning 1.1 Oppdragsgiver Helse Midt-Norge RHF (Org. NO 983 658 776) er oppdragsgiver og vil være kontraktspart. Avtalen skal i kontraktsperioden benyttes av: St. Olavs Hospital HF Org. NO 883 974 832 Hvis det i kontraktsperioden skjer omstrukturering av helseforetakene eller endring i organiseringen av spesialisthelsetjenesten, vil det angitte helseforetaks rettsetterfølgere kunne benytte kontrakten. 1.2 Helse Midt-Norge RHF Helse Midt-Norge RHF er ett av fire regionale helseforetak i landet og har overordnet ansvar for alle offentlige sykehus og annen spesialisthelsetjeneste for over 697 000 innbyggere i Møre og Romsdal, Sør-Trøndelag og Nord-Trøndelag. -

Velkommen Til Frøya Og Hitra

Velkommen til Frøya og Hitra Fakta – Frøya og Hitra • Frøya – den fremste øya • Hitra • 76 meter over havet • Befolkning: 5 088 (1.kv 2020) • 5400 små og store øyer, holmer og skjær • 231 km2 landareal • Pendling – ut: 429, inn: 516 • 2255 km kystlinje (2,7 % av Norges • 2 260 eneboliger kystlinje) • 1 927 fritidsboliger • Befolkning: 5 166 (1.kv 2020) • Pendling – ut: 390, inn: 660 • 1 990 eneboliger • 1 070 fritidsboliger Befolkningsutvikling Sysselsetting Prosentvis endring i antall sysselsatte 4.kvartal 2008 til 4. kvartal 2018 Utvikling i befolkning og sysselsetting i kommunene i Trøndelag 40,0 % Vekst befolkning Vekst befolkning Nedgang arbeidsplasser Vekst arbeidsplasser 30,0 % Skaun Frøya 20,0 % Stjørdal Trondheim Malvik Melhus Hitra Vikna Levanger Orkdal 2019 (prosent) 2019(prosent) 10,0 % Klæbu Bjugn - Steinkjer Overhalla Verdal Ørland Frosta Midtre Gauldal Oppdal Namsos Åfjord Selbu Nærøy Inderøy Røros Grong Hemne Snillfjord Meldal 0,0 % Indre Fosen Agdenes Holtålen Høylandet Meråker Leka Rindal Flatanger Røyrvik Snåsa Roan Lierne Rennebu Namsskogan Osen Tydal Namdalseid -10,0 % Fosnes Endring Endring befolkning 2009 Verran -20,0 % Nedgang befolkning Nedgang befolkning Nedgang arbeidsplasser Vekst arbeidsplasser -30,0 % -20,0 % -10,0 % 0,0 % 10,0 % 20,0 % 30,0 % Endring sysselsetting 4.kvartal 2008-4. kvartal 2018 (prosent) Næringsliv • Hitra og Frøya står for: • ca. 51 % av eksporten av fisk fra Trøndelag • ca. 33 % av vareeksporten fra Trøndelag • ca. 18 % av den totale eksporten fra Trøndelag Helhetlig ROS • Risikokatalysatorer En risikokatalysator er en hendelse som kan påvirke en annen hendelse (som inntreffer samtidig) slik at konsekvensene av denne forsterkes. (..) Parallelle hendelser vil derfor kunne påvirke beredskapsevnen til kommunen opp mot kapasitet på ressursene. -

Fylkesveg 6708 I Malvik Kommune - Tilbakemelding På Varsel Om Igangsetting Av Detaljregulering for Vikhammer Nedre

Agraff Arkitektur AS Mellomila 56 7018 TRONDHEIM Behandlende enhet: Saksbehandler/telefon: Vår referanse: Deres referanse: Vår dato: Region midt Jan-Kristian Janson / 90412554 19/11753-2 17.01.2019 Fylkesveg 6708 i Malvik kommune - Tilbakemelding på varsel om igangsetting av detaljregulering for Vikhammer Nedre Viser til deres brev av 14.01.2019. Statens vegvesen har ansvar for å se etter at føringene i Nasjonal Transportplan (NTP), statlige planretningslinjer for samordnet bolig-, areal- og transportplanlegging, vegnormalene og andre nasjonale og regionale arealpolitiske føringer blir ivaretatt i planleggingen. Vi uttaler oss som forvalter av riks- og fylkesveg, henholdsvis på vegne av staten og fylkeskommunen, og som statlig fagstyresmakt med sektoransvar på transportområdet. Arealpolitiske føringer for planarbeidet NTP (2018-2029) har følgende overordnet mål: Et transportsystem som er sikkert, fremmer verdiskaping og bidrar til omstilling til lavutslippssamfunnet. ‘Nasjonale forventninger til kommunal og regional planlegging’ skisserer noen av ut- fordringene. En aktiv regional og kommunal planlegging som samordner bolig-, areal- og transportpolitikken og som reduserer transportbehovet er nødvendig for blant annet å nå målene for miljøpolitikken. Dette er en sentral forventning. Denne forventningen understrekes gjennom ‘Statlige planretningslinjer for samordnet bolig-, areal- og transportplanlegging’. Disse sier bl.a. at planlegging av utbyggingsmønsteret og transportsystemet må samordnes for å oppnå effektive løsninger slik at transportbehovet