Copyright by Médar De La Cruz Serrata 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Three the Genesis of the Black Legend

1 Chapter Three The Genesis of the Black Legend "Todo esto yo lo vide con mis ojos corporates mortales." Bartolomé de las Casas, 1504. "I saw all this with my very own eyes." “ I watched as the Lamb opened the first of the seven seals. Then I heard one of the four living creatures say in a voice like thunder, “Come!” I looked, and there before me was a white horse! Its rider held a bow, and he was given a crown, and he rode out as a conqueror bent on conquest.” [Revelation 6:1,2] Or, in Latin as Las Casas may have been accustomed to reading it “Et vidi quod aperuisset agnus unum de septem signaculis et audivi unum de quattuor animalibus dicentem tamquam vocem tonitrui veni. Et vidi et ecce equus albus et qui sedebat super illum habebat arcum et data est ei corona et exivit vincens ut vinceret.” 1Perhaps he also read it in Spanish: “Vi cuando el Cordero abrió uno de los sellos, y oí a uno de los cuatro seres vivientes decir como con voz un trueno: Ven y mira. Y miré, y he aquí un caballo banco; y el que lo montaba tenía un arco; le fue dada una corona, y salió venciendo, y para vencer.” "Like a partridge that hatches eggs it did not lay is the man who gains riches by unjust means." Jeremiah 17:11 Next to climbing aboard a ship for a long journey, there is probably nothing more exciting than getting off that same ship! Especially if after a long voyage, sometimes made terrifying by the perils of the sea. -

ISSUE 20 La Ciudad En La Literatura Hispánica De Los Siglos XIX, XX Y XXI (December 2008) ISSN: 1523-1720

ISSUE 20 La ciudad en la literatura hispánica de los siglos XIX, XX y XXI December, 2008 Dedicamos este número a todos los autores que han participado en CIBERLETRAS con sus ensayos y también a los lectores que han seguido su trayectoria durante estos diez años. Muchas gracias a todos. ISSUE 20 La ciudad en la literatura hispánica de los siglos XIX, XX y XXI (December 2008) ISSN: 1523-1720 Sección especial: la ciudad en la literatura hispánica de los siglos XIX, XX y XXI • Pilar Bellver Saez Tijuana en los cuentos de Luis Humberto Crosthwaite: el reto a la utopía de las culturas híbridas en la frontera • Enric Bou Construcción literaria: el caso de Eduardo Mendoza • Luis Hernán Castañeda Simulacro y Mimesis en La ciudad ausente de Ricardo Piglia • Bridget V. Franco La ciudad caótica de Carlos Monsiváis • Cécile François Méndez de Francisco González Ledesma o la escritura de una Barcelona en trance de desaparición • Oscar Montero La prosa neoyorquina de Julia de Burgos: "la cosa latina" en "mi segunda casa" • María Gabriela Muniz Villas de emergencia: lugares generadores de utopías urbanas • Vilma Navarro-Daniels Los misterios de Madrid de Antonio Muñoz Molina: retrato callejero y urbano de la capital española a finales de la transición a la democracia • Rebbecca M. Pittenger Mapping the Non-places of Memory: A Reading of Space in Alberto Fuguet's Las películas de mi vida • Damaris Puñales-Alpízar La Habana (im) posible de Ponte o las ruinas de una ciudad atravesada por una guerra que nunca tuvo lugar • Belkis Suárez La ciudad y la violencia en dos obras de Fernando Vallejo 2 ISSUE 20 La ciudad en la literatura hispánica de los siglos XIX, XX y XXI (December 2008) ISSN: 1523-1720 Ensayos/Essays • Valeria Añón "El polvo del deseo": sujeto imaginario y experiencia sensible en la poesía de Gonzalo Rojas • Rubén Fernández Asensio "No somos antillanos": La identidad puertorriqueña en Insularismo • Roberto González Echevarría Lezama's Fiestas • Pablo Hernández Hernández La fotografía de Luis González Palma. -

Quantifying Arbovirus Disease and Transmission Risk at the Municipality

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.20143248; this version posted July 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 1 Title: Quantifying arbovirus disease and transmission risk at the municipality 2 level in the Dominican Republic: the inception of Rm 3 Short title: Epidemic Metrics for Municipalities 4 Rhys Kingston1, Isobel Routledge1, Samir Bhatt1, Leigh R Bowman1* 5 1. Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Imperial College London, UK 6 *Corresponding author 7 [email protected] 8 9 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. 1 medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.20143248; this version posted July 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 2 10 Abstract 11 Arboviruses remain a significant cause of morbidity, mortality and economic cost 12 across the global human population. Epidemics of arboviral disease, such as Zika 13 and dengue, also cause significant disruption to health services at local and national 14 levels. This study examined 2014-16 Zika and dengue epidemic data at the sub- 15 national level to characterise transmission across the Dominican Republic. -

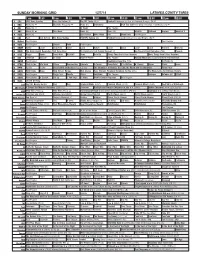

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

2714 Surcharge Supp Eng.V.1

Worldwide Worldwide International Extended Area Delivery Surcharge ➜ Locate the destination country. ➜ Locate the Postal Code or city. ➜ If the Postal Code or city is not listed, the entry All other points will apply. ➜ A surcharge will apply only when a “Yes” is shown in the Extended Area Surcharge column. If a surcharge applies, add $30.00 per shipment or $0.30 per pound ($0.67 per kilogram), whichever is greater, to the charges for your shipment. COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE ARGENTINA BOLIVIA (CONT.) BRAZIL (CONT.) CHILE (CONT.) COLOMBIA (CONT.) COLOMBIA (CONT.) DOMINICAN REPUBLIC (CONT.) DOMINICAN REPUBLIC (CONT.) 1891 – 1899 Yes Machacamarca Yes 29100 – 29999 Yes El Bosque No Barrancabermeja No Valledupar No Duarte Yes Monte Plata Yes 1901 – 1999 Yes Mizque Yes 32000 – 39999 Yes Estación Central No Barrancas No Villa de Leiva No Duverge Yes Nagua Yes 2001 – 4999 Yes Oruro Yes 44471 – 59999 Yes Huachipato No Barranquilla No Villavicencio No El Cacao Yes Neiba Yes 5001 – 5499 Yes Pantaleón Dalence Yes 68000 – 68999 Yes Huechuraba No Bogotá No Yopal No El Cercado Yes Neyba Yes 5501 – 9999 Yes Portachuelo Yes 70640 – 70699 Yes Independencia No Bucaramanga -

El Encuentro Con Anacaona: Frederick Caribe Albion Über Y La Historia Del

EL ENCUENTRO CON ANACAONA: FREDERICK ALBION ÜBER Y LA HISTORIA DEL CARIBE AUTÓCTONO* Peter Hu/me acia el final de la novela de Frederick Albion Ober titulada The Last of the Arawaks: A Story of Adventure on the /stand of San Domingo (1901 ), situada en 1899, uno de los héroes, Arthur Strong, joven proveniente de la Nueva Inglaterra, es llevado a presencia de la Reina Anacaona, descendiente directa de la cacica taína del mismo nombre a quien Nicolás de Ovando ejecutó en 1503: • Debo expresar mi reconocimiento a Arcadio Díaz Quiñones y a Léon-Fran~ois Hoffmann, por su invitación a participar en la conferencia en la que se basa el presente volumen, así como por todo el aliento que me han dado; y también a los demás participantes en el coloquio final : Amy Kaplan, Rolena Adorno, Ken Milis y Bill Gleason. El Profesor lrving Leonard (por intermediación de Rolena Adorno) aportó algunas referencias muy valiosas. La investigación correspondiente a este trabajo la inicié cuando era yo becario de la Fundación Rockefeller por Humanidades en la Uni versidad de Maryland, y quisiera expresar mi agradecimiento a los miembros del Departamento de Español y Portugués, de College Park, por la hospitalidad y el apoyo que me brindaron. Facilitó mi investigación sobre Frederick Ober la ayuda experta que me ofrecieron los encargados de los archivos de la Smithsonian lnstitution, de la Sociedad Histórica de Beverly y de las Bibliotecas de la Universidad de Washington, en Seattle. 76 Peter Hulme Puesto que allí, ante él, a unos tres metros de distancia, se encontraba la más bella mujer que jamás hubiera contemplado. -

Año 86 • Enero-Junio De 2017 • No. 193 El Contenido De Este Número De Clío, Año 86, No

Año 86 • Enero-junio de 2017 • No. 193 El contenido de este número de Clío, año 86, no. 193, fue aprobado por la Comisión Editorial el día 19 de mayo de 2017, integrada por los Miembros de Número Dr. José Luis Sáez Ramo; Dr. Amadeo Julián; Lic. Raymundo M. González de Peña; y el Miembro Correspondiente Nacional Dr. Santiago Castro Ventura, y refrendado por la Junta Directiva en su sesión del día 24 de mayo de 2017, conforme a las disposiciones del Artículo 24, apartado 1) de los Estatutos de la Academia Dominicana de la Historia. Junta Directiva (agosto de 2016- agosto de 2019): Da. Mu-Kien Adriana Sang Ben, presidenta; Lic. Adriano Miguel Tejada, vicepresidente; Dr. Amadeo Julián, secretario; Lic. Manuel A. García Arévalo, tesorero; y Lic. José del Castillo Picharlo, vocal. © De la presente edición Academia Dominicana de la Historia, 2017 Calle Mercedes No. 204, Zona Colonial Santo Domingo, República Dominicana E-mail:[email protected] La Academia Dominicana de la Historia no se hace solidaria de las opiniones emitidas en los trabajos insertos en Clío, de los cuales son únicamente Responsables los autores. (Sesión del 10 de junio de 1952) La Academia Dominicana de la Historia no está obligada a dar explicaciones por los trabajos enviados que no han sido publicados. Editor: Dr. Emilio Cordero Michel Diagramación: Licda. Guillermina Cruz Impresión: Editora Búho Calle Elvira de Mendoza No. 156 Santo Domingo, República Dominicana Impreso en la República Dominicana Printed in the Dominican Republic Índice CLÍO Órgano de la Academia Dominicana de la Historia Año 86 • Enero-junio de 2017 • No. -

Santo Domingo, Nuestra Ciudad Capital Y Primada De América

Mensaje del Ministro de Turismo ¡Bienvenidos a República Dominicana! En nombre del Ministerio de Turismo de República Dominicana, es un placer darles la bienvenida a Santo Domingo, nuestra ciudad capital y primada de América. La exploración del Nuevo Mundo se origina en la Ciudad Colonial, localizada dentro del moderno y sofisticado Santo Domingo que conocemos hoy. Santo Domingo de Guzmán fue fundada por el Gobernador Bartolomé Colón en Agosto de 1496. Con más de 500 años de cultura, sus atributos le ofrecen al mundo un vivo testimonio del pasado que nos formó como nación. En la Ciudad Colonial los visitantes pueden conocer el Alcázar de Colón, así como también visitar la primera universidad y la Catedral Primada de América. Aquí yacen edificios históricos sobre auténticas calles adoquinadas que una vez fueron visitadas por los conquistadores españoles. Esta legendaria ciudad es rica en museos, monumentos y restaurantes, y cuenta además con terminales para cruceros, gran variedad de tiendas, interesante arquitectura y mucho más. Reposando sobre el Mar Caribe, Santo Domingo es ahora un importante y sofisticado centro comercial, con docenas de museos, teatros y sitios históricos como el Faro a Colón. Con dos aeropuertos internacionales, excelente infraestructura y puertos marítimos, Santo Domingo se convierte en la puerta de entrada a miles de kilómetros de costas dominicanas, deslumbrantes montañas llenas de cascadas, exótica cocina e innumerables opciones de arte y entretenimiento. República Dominicana lo tiene todo: playas vírgenes, -

Ever Faithful

Ever Faithful Ever Faithful Race, Loyalty, and the Ends of Empire in Spanish Cuba David Sartorius Duke University Press • Durham and London • 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Tyeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sartorius, David A. Ever faithful : race, loyalty, and the ends of empire in Spanish Cuba / David Sartorius. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5579- 3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5593- 9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Blacks— Race identity— Cuba—History—19th century. 2. Cuba— Race relations— History—19th century. 3. Spain— Colonies—America— Administration—History—19th century. I. Title. F1789.N3S27 2013 305.80097291—dc23 2013025534 contents Preface • vii A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s • xv Introduction A Faithful Account of Colonial Racial Politics • 1 one Belonging to an Empire • 21 Race and Rights two Suspicious Affi nities • 52 Loyal Subjectivity and the Paternalist Public three Th e Will to Freedom • 94 Spanish Allegiances in the Ten Years’ War four Publicizing Loyalty • 128 Race and the Post- Zanjón Public Sphere five “Long Live Spain! Death to Autonomy!” • 158 Liberalism and Slave Emancipation six Th e Price of Integrity • 187 Limited Loyalties in Revolution Conclusion Subject Citizens and the Tragedy of Loyalty • 217 Notes • 227 Bibliography • 271 Index • 305 preface To visit the Palace of the Captain General on Havana’s Plaza de Armas today is to witness the most prominent stone- and mortar monument to the endur- ing history of Spanish colonial rule in Cuba. -

La Poesía Sorprendida: Estudio Métrico Y Poético De Varios De Sus Autores

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA TESIS DOCTORAL La poesía sorprendida: estudio métrico y poético de varios de sus autores MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Pablo Reyes Pérez Directora Almudena Mejías Alonso Madrid © Pablo Reyes Pérez, 2019 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOLOGIA DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGIA ESPAÑOLA IV (BIBLIOGRAFIA ESPAÑOLA Y LITERATURA HISPANOAMERICANA) TESIS DOCTORAL LA POESÍA SORPRENDIDA: ESTUDIO MÉTRICO Y POÉTICO DE VARIOS DE SUS AUTORES Presentada por PABLO REYES PEREZ Directora ALMUDENA MEJÍAS ALONSO Madrid, 2019 PABLO REYES PEREZ LA POESÍA SORPRENDIDA: ESTUDIO MÉTRICO Y POÉTICO DE VARIOS DE SUS AUTORES ALMUDENA MEJÍAS ALONSO TESIS DOCTORAL DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGIA ESPAÑOLA IV FACULTAD DE FILOLOGIA (BIBLIOGRAFIA ESPAÑOLA Y LITERATURA HISPANOAMERICANA) UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Madrid, 2019 A Darlyn y a Arturo A Rafael y a Isidora A mis hermanos y hermanas Agradecimientos En primer lugar quiero agradecer a Darlyn, por el vínculo que nos une, el mismo que también nos separa, a veces. Y a Arturo, por esa paloma que aún durmiendo vuela en sus ojos. Ellos: coautores y víctimas de todo este proceso. Vayan mis más sinceros agradecimientos a mi asesora, la doctora Almudena Mejías Alonso, por todo lo que me ha facilitado en la preparación de este trabajo, y por todo lo que me ha soportado. Al profesor Miguel Ibarra, sin cuyo apoyo y consejos hubiera sido imposible la realización de este proyecto; agradecimiento que deseo hacer extensivo a todos los estudiantes amigos, ayudantes y colaboradores del Departamento de Letras de la Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo, junto a los que han transcurrido estos años de trabajo doctoral y que, de una u otra manera, han apoyado mi labor investigadora y mi aislamiento para tales fines. -

Manuel Ruano: “Rilke Suena En Mis Oídos Como Un Violín Desvelado”

Manuel Ruano: “Rilke suena en mis oídos como un violín desvelado” Entrevista realizada por Rolando Revagliatti Manuel Ruano nació el 15 de enero de 1943 en el barrio Saavedra, de Buenos Aires (ciudad en la que reside), la Argentina. Habiendo realizado estudios sobre literatura española, se especializó en Siglo de Oro Español. Es profesor honorario en la Universidad Nacional de San Marcos y en la Universidad Nacional San Martín de Porres, de Lima, Perú, donde en 1992 fundó la revista de poesía latinoamericana “Quevedo”. Entre 1969 y 2007 fueron publicados en su país, así como en Venezuela, Ecuador, México y Perú, sus poemarios “Los gestos interiores” (Primer Gran Premio Internacional de Poesía de Habla Hispana “Tomás Stegagnini”), “Según las reglas”, “Son esas piedras vivientes” (Edición Premio Nacional de Poesía de la Asociación de Escritores de Venezuela, Caracas, 1982), “Yo creía en el Adivinador orfebre”, “Mirada de Brueghel” (Fondo de Cultura Económica, México, 1990), “Hipnos”, “Los cantos del gran ensalmador” (Monte Ávila Editores, Caracas, 2005), “Concertina de los rústicos y los esplendorosos”. En 2010 da a conocer su libro de cuentos “No son ángeles del amanecer”. Y en Caracas el volumen “Lautréamont y otros ensayos” (Celarg —Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos “Rómulo Gallegos”—, 2010), donde también se editó el CD “Manuel Ruano en su tinta”(poemas). En su condición de antólogo, citamos “Poesía nueva latinoamericana” (1981), “Y la espiga será por fin espiga” (1987), “Cantos australes” (1995), “Poesía amorosa de América Latina” (1995),“Crónicas de poeta” (sobre artículos de César Vallejo, 1996), “Obra poética de Olga Orozco” (con estudio preliminar, 2000), “Cartas del destierro y otras orfandades” (correspondencia de César Vallejo, 2006),“Olga Orozco – Territorios de fuego para una poética” (Sevilla, España, 2010), “Vivir en el poema – Homenaje a Carlos Germán Belli” (Sevilla, España, 2013). -

Revista Clío No

L Color L L etras ennegro omo: omo : P 21milímetr antone 221c os Año 82 • Julio-diciembre de 2013 • No. 186 sesquicentenario yalDr Homenaje alaGuerradeRestauraciónen su Año 82•Julio-diciembre de2013• No.186 en elcincuentenariodesuasesinato . Manuel Aurelio T avárez Justo Año 82 • Julio-diciembre de 2013 • No. 186 Homenaje a la Guerra de la Restauración en su sesquicentenario y al Dr. Manuel Aurelio Tavárez Justo en el cincuentenario de su asesinato El contenido de este Clío, año 82, No 186, fue aprobado por la Comisión Editorial en las sesiones celebradas los días 4 de septiembre, 2 de octubre y 6 de noviembre de 2013, integrada por los Académicos de Número: Lic. José Felipe Chez Checo; Dr. Amadeo Julián; y Dr. José Luis Sáez Ramo. Junta Directiva (agosto 2013-2016): Lic. Bernardo Vega Boyrie, presidente; Dra. Mu-Kien Adriana Sang Ben, vicepresidenta; Lic. Adriano Miguel Tejada, secretario; Lic. José Felipe Chez Checo, tesorero; y Dr. José Luis Sáez, vocal. © De la presente edición Academia Dominicana de la Historia, 2013 La Academia Dominicana de la Historia no se hace solidaria de las opiniones emitidas en los trabajos insertos en Clío, de los cuales son únicamente Responsables los autores. (Sesión del 10 de junio de 1952) La Academia Dominicana de la Historia no está obligada a dar explicaciones por los trabajos enviados que no han sido publicados. Editor: Dr. Emilio Cordero Michel Diagramación: Licda. Guillermina Cruz Impresión: Editora Búho Calle Elvira de Mendoza No. 156 Santo Domingo, República Dominicana Impreso en la República Dominicana Printed in the Dominican Republic Sumario Órgano de la AcademiaCLÍO Dominicana de la Historia Año 82 • Julio-diciembre de 2013 • No.