The Colors and Shadows of My Word(S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

Vida Cotidiana Durante La Revolución Mexicana Alejandro Rodriguez-Mayoral University of Texas at El Paso, Alejandro [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2015-01-01 Zapatistas: Vida cotidiana durante la Revolución Mexicana Alejandro Rodriguez-Mayoral University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Rodriguez-Mayoral, Alejandro, "Zapatistas: Vida cotidiana durante la Revolución Mexicana" (2015). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1138. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1138 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ZAPATISTAS: VIDA COTIDIANA DURANTE LA REVOLUCIÓN MEXICANA ALEJANDRO RODRIGUEZ-MAYORAL Departamento de Historia APROBADO: Samuel Brunk, Ph.D., Chair Yolanda Chávez Leyva, Ph.D. Sandra McGee Deutsch, Ph.D. Howard Campbell, Ph.D. Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © por Alejandro Rodriguez-Mayoral 2015 Dedicatoria Dedico esta disertación a Dios. ZAPATISTAS: VIDA COTIDIANA DURANTE LA REVOLUCIÓN MEXICANA por ALEJANDRO RODRIGUEZ-MAYORAL, Máster DISERTACIÓN Presentada a la facultad de la Escuela de Graduados de la Universidad de Texas en El Paso en cumplimiento parcial de los requerimientos para el Grado de DOCTOR Departamento de Historia UNIVERSIDAD DE TEXAS EN EL PASO Mayo 2015 AGRADECIMIENTOS Esta tesis doctoral fue escrita con el apoyo incondicional de amigos, familiares y profesores durante mi preparación académica, proceso de investigación y escritura de la misma. Deseo hacer presente mi gratitud a Servando Ortoll, Avital Bloch, Charles Ambler, Cheryl E. -

Performing the Mexican Revolution in Neoliberal Times

ABSTRACT Since the time of the Mexican Revolution of 1910, images associated with this nation-defining event have been presented in an array of media and cultural productions. Within the past two decades these images have been re-imagined, re-coded and re/de- constructed in reaction to social and cultural changes associated with a crisis of political legitimation and the demise of hegemonic revolutionary ideology, as espoused by the long-ruling Party of the Institionalized Revolution (PRI), amid the generalized implementation of neoliberal policies in the county. My dissertation argues that the ascendance of neoliberalism, with the opening of Mexican economic and political systems, has resulted in changes in the socio-cultural work performed by the Revolution- Nation-Gender triad. This trinity, solidified in the post-Revolutionary national imaginary, weaves the three notions together such that as hegemonic discourses of Revolutionary nationalism enter in crisis, discourses of gender are also destabilized. The dissertation consists of three main sub-arguments. First, I argue that the discourse(s) surrounding Revolutionary heroes has been integral to the (re)definition of the Mexican nation and that analyzing recodings of this discourse through the example of Emiliano Zapata reveals a destabilization of hegemonic nationalism. These changes have allowed alternatives to surface both in Mexico and across the border as part of a recoded ii transnational Revolutionary nationalism. As cracks opened in the Revolutionary edifice allowing alternatives to emerge, they have also opened space for alternative gender discourses. I next argue that a close analysis of representations of masculine gender roles as manifested in a variety of cultural texts, specifically through Revolutionary icons Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, reveals a crisis of the macho archetype in the contemporary Mexican nation. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Elements of an Altar Ancient Ofrenda 9Th Annual Día De Los Muer Tos Festival Exhibi T Gallery Guide

Ancient Ofrenda Elements of an Altar 9th Annual Día de los Muer tos Festival Exhibit Gallery Guide Additional Information on Artworks and Artists and some Spanish Translations ASU Museum of Anthropology Fall 2008 Susan Elizalde-Holler Transformation Ceramic All that is of this earth will undergo transformation. Vessels made of earth and transformed may be viewed as symbols or metaphors, yet to some they are merely utilitarian instruments. If vessels could speak, the stories they could tell of those who passed along the very earth they are made from. Time, tradition, and transformation are our experiences during this time on earth. At this particular moment in time, this small clay vessel becomes an offer- ing, a special offering - one of more transformations yet to come. Mary-Beth Buesgen Balancing the Elements Ceramic, raku Raku is a low-fi re technique where clay work is quickly heated to red hot temperature and then taken out of the kiln and reduced in combustible ma- terial. The main material I used was the thoughts, prayers, and tributes left on paper at the altars from last year’s Day of the Dead. I wanted to use the paper to assist in the representation of the four elements earth, air, fi re and water in a Raku context. Everyone’s wishes and words left behind for loved ones is now transformed in a beautiful work of art. Guillermo Valenzuela Santa Muerte (Clay) Santa Muerte Luna (Oil on Canvas) The cult to death has existed in Mexico for more than 3,000 years. The fi rst residents of what is now Mexico conceived death as something necessary and that happens to all beings in nature. -

2Security Lockdown 7Surviving Semester

THE OUR grotto LADY OF LOURDES ACADEMY MIAMI, FLORIDA VOLUME 50/ISSUE 6 May 2013 www.olla.org/grotto/may C SHOO L’S OUT SECURITY LOCKDOWN SURVIVING SEMESTER SPORTS SUCCESSES Check out the effects of Boston Reminisce over the hIghlights of inside For a HOW TO guide to surviving 2 bombing on the government’s 7the last few months of the school year, 16 each superb sports teams’ victories security policies. check out this month’s issue. from the entire year. peek 2 news | the grotto |may 2013 The State of Our Nation(al Security) KATHRYN MELLINGER These acts of terror have been influenced organizations. by the extremist teachings of an American As far as Dzhokhar goes, he has been A sense of closure has overcome the cleric named Anwar al-Awlaki. assigned multiple public defenders who - nation with the capturing of one of the The fanatic teachings clearly influenced will plead his case in federal court in hopes Boston bombers, Dzhorkhar Tsarnaev. 53% the actions of the terrorists who decided of avoiding the death penalty. Though the suspect has been stabilized, to attack the Boston marathon on Patriot’s According to U.S. News, it is very feel that the govern he is not capable of speaking due to a self Day, after finishing the homemade bombs likely that the attorneys will bargain with inflicted gunshot wound to the neck. early. The bombs were created using prosecutors on the idea that Dzhokhar was ment has not taken In order to gain information regarding pressure cookers in the apartment of not fully aware of his actions and did not enough measures the recent terror attacks, the FBI denied Tamerlan, the older suspect. -

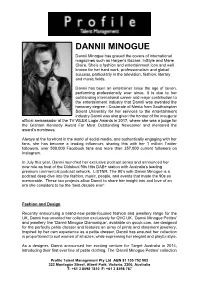

Dannii Minogue

DANNII MINOGUE Dannii Minogue has graced the covers of international magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, InStyle and Marie Claire. She’s a fashion and entertainment icon and well known for her hard work, professionalism and global success, particularly in the television, fashion, literary and music fields. Dannii has been an entertainer since the age of seven, performing professionally ever since. It is due to her outstanding international career and major contribution to the entertainment industry that Dannii was awarded the honorary degree - Doctorate of Media from Southampton Solent University for her services to the entertainment industry Dannii was also given the honour of the inaugural official ambassador at the TV WEEK Logie Awards in 2017, where she was a judge for the Graham Kennedy Award For Most Outstanding Newcomer and mentored the award’s nominees. Always at the forefront in the world of social media, and authentically engaging with her fans, she has become a leading influencer, sharing this with her 1 million Twitter followers, over 500,000 Facebook fans and more than 357,000 current followers on Instagram. In July this year, Dannii launched her exclusive podcast series and announced her new role as host of the Oldskool 90s Hits DAB+ station with Australia’s leading premium commercial podcast network, LiSTNR. The 90’s with Dannii Minogue is a podcast deep dive into the fashion, music, people, and events that made the 90s so memorable. These two projects allow Dannii to share her insight into and love of an era she considers to be the ‘best decade ever’. -

Laudato-Si-Earth-Charter-Carta-De-La-Tierra-1-4

“Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.” Voices of the Earth Charter Initiative Responding to Encyclical Laudato Si’ Voces de la Iniciativa de la Carta de la Tierra Respondiendo a la Encíclica Laudato Si’ “Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.” Voices of the Earth Charter Initiative Responding to Encyclical Laudato Si’ Essays by : Leonardo Boff, Fritjof Capra, Joe Holland, José Matarrita, Elizabeth May, Steven C. Rockefeller, Awraham Soetendorp, Mary Evelyn Tucker, John Grim Compilers: Alicia Jiménez, Mirian Vilela editorial Universidad Técnica Nacional Primera edición / First edition: 2017 Diseño de portada / Cover design: Federico Arce Jiménez Diagramación / Layout: Federico Arce Jiménez y Emily Paniagua López Revisión de estilo / Copy editing: Lorna Battista y Fiona Jane Stitfold Traductores / Translators: Amandine Pieux, Mª José Gavito Milano, Alicia Jiménez y José Matarrita Coordinación editorial / Publisher: Consejo Editorial UTN / National Technical University of Costa Rica Press La EUTN es miembro del Sistema de Editorales Universitarias de Centroamérica SEDUCA, perteneciente al Consejo Superior Universitario Centroamericano CSUCA. -

Teaching an Indigenous Sociology: a Response to Current Debate Within Australian Sociology

TEACHING AN INDIGENOUS SOCIOLOGY: A RESPONSE TO CURRENT DEBATE WITHIN AUSTRALIAN SOCIOLOGY KATHLEEN JULIE BUTLER B.SOC.SC, M.SOC.SC THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY FACULTY OF EDUCATION & ARTS THE UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE MARCH, 2009. This work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this Thesis is the result of original research, the greater part of which was completed subsequent to admission to candidature for the degree. Signature: …………………… Date: …….. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Finding the Sociology of Indigenous Issues 1 Chapter 1. Disciplinary and Methodological Adventures 12 Readers beware: This is not orthodox! 12 Autoethnography, Tribalography and Story 27 Chapter 2. Sociological Literature: Reviewing the Silence 36 Chapter 3. (De)Constructing Aboriginal Perspectives 52 Which form of identity? 52 “Visual Aboriginality” and the trauma of stereotypical judgement 59 Chapter 4. Why my family don’t “dress like Aborigines” 73 My Tribalography: An Alternative Conception of Urban Indigenous Identity 80 Chapter 5. From Film to Blogs: Other Resources for a Sociology of Indigenous Issues 95 Voting, Aboriginality and the Media in the classroom 107 Chapter 6. -

Dannii Minogue

DANNII MINOGUE Dannii Minogue has graced the covers of international magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, InStyle and Marie Claire. She’s a fashion and entertainment icon and well known for her hard work, professionalism and global success, particularly in the television, fashion, literary and music fields. Dannii has been an entertainer since the age of seven, performing professionally ever since. It is due to her outstanding international career and major contribution to the entertainment industry that Dannii was awarded the honorary degree - Doctorate of Media from Southampton Solent University for her services to the entertainment industry Dannii was also given the honour of the inaugural official ambassador at the TV WEEK Logie Awards in 2017, where she was a judge for the Graham Kennedy Award For Most Outstanding Newcomer and mentored the award’s nominees. Always at the forefront in the world of social media, and authentically engaging with her fans, she has become a leading influencer, sharing this with her 1.13 million Twitter followers, over 440,000 Facebook fans and more than 300,000 current followers on Instagram. Television and Theatre 2019 saw Dannii return to Australian screens as one of four superstar panellists in the worldwide phenomenon and mystery singing show, The Masked Singer Australia. The show features 12 celebrity contestants who perform behind bizarre disguises, with the panel and audience trying to determine, from clues provided to them, who is behind the mask. A 'bonkers' entertainment show, The Masked Singer Australia premiered on Network Ten reaching a national audience of more than 3 million viewers over its first two nights on air. -

En El Jardín De Los Vientos Obra Poética

EN EL JARDÍN DE LOS VIENTOS OBRA POÉTICA (1974-2014) ACADEMIA NORTEAMERICANA DE LA LENGUA ESPAÑOLA (ANLE) D. Gerardo Piña-Rosales Director D. Jorge I. Covarrubias Secretario D. Daniel R. Fernández Coordinador de Información (i) D. Joaquín Segura Censor D. Emilio Bernal Labrada Tesorero D. Eugenio Chang-Rodríguez Director del Boletín D. Carlos E. Paldao Bibliotecario (i) * Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española (ANLE) P.O. Box 349 New York, NY, 10106 U.S.A. Correo electrónico: [email protected] Sitio Institucional: www.anle.us Copyright © por ANLE. Todos los derechos reservados. Esta publicación no puede ser reproducida, ni en un todo ni en parte, ni registrada en o transmi- tida por un sistema de recuperación de información, en ninguna forma ni por ningún medio, sea fotoquímico, electrónico, magnético, mecánico, electroóptico, o cualquier otro, sin el permiso por escrito de la Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española. Luis Alberto Ambroggio EN EL JARDÍN DE LOS VIENTOS OBRA POÉTICA (1974-2014) Carlos E. Paldao y Rosa Tezanos-Pinto Editores Colección Pulso Herido Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española 2014 En el jardín de los vientos. Obra poética (1974-2014) Luis Alberto Ambroggio Colección Pulso Herido, 2 Nueva York: Editorial Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española (ANLE) © Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española (ANLE) © Luis Alberto Ambroggio © Carlos E. Paldao y Rosa Tezanos-Pinto © Fotografías Gerardo Piña-Rosales Primera Edición. 2014 ISBN: 978-0-9903455-1-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2014940499 Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española (ANLE) P. O .Box 349 New York, NY, 10106 U. S. A. Correo electrónico: [email protected] Sitio Institucional: www.anle.us Ilustración de portada y fotografías: Gerardo Piña-Rosales Edición y supervisión: Carlos E. -

By Maxwell Clark

Poesies by Maxwell Clark ―[...]to kill and destroy all the wicked, id est, all that differ from them, that they, to wit, the saints, may rule, and who therefore seek to make all things common […] evidently appears to proceed from pride and covetousness, and not from purity or conscience[…]‖ —Barclay‘s Apology EPC Digital Edition, 2014 ©Maxwell Clark I Write You Poesy Now, Seeing? I write you poesy now, seeing? It is poesy and about the things and you. Do you like? I am gladness of it too. I Hear Birds Outside Drear cardboard sensuousness, Is this universal now too? Sparkle for me, drear birdies then, Go a sparkling in your remoteness-dens, Sparkle, sparkle, sing and warble, Make me a'glow---as though remade of marble, And so now I am, I am, I am, And so verily, verily am I then. Song Song this is a song, it's about how i'm singing you a song, i love it so much, i've been singing it all along; it is my song i sing to you, just me to you, yes, you, so to you it belongs, unless i am untrue; love this song, i've been singing it so wrongly so longly long. Panda Peace The pandas are making the peace happen. They are doing their best ever. Nobody else knows the signal patterns. Please let them win; please, win. Poesy is Madness This delicate little essay will explore you, as you are for me, Or as I hear your voice whisper from a measureless proximity.