Elements of an Altar Ancient Ofrenda 9Th Annual Día De Los Muer Tos Festival Exhibi T Gallery Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. P.O

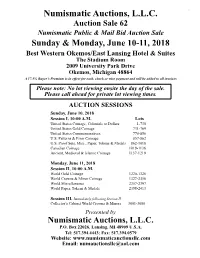

NumismaticNumismatic Auctions, LLC Auctions, Auction Sale 62 - June 10-11, 2018 L.L.C. Auction Sale 62 Numismatic Public & Mail Bid Auction Sale Sunday & Monday, June 10-11, 2018 Best Western Okemos/East Lansing Hotel & Suites The Stadium Room 2009 University Park Drive Okemos, Michigan 48864 A 17.5% Buyer’s Premium is in effect for cash, check or wire payment and will be added to all invoices Please note: No lot viewing onsite the day of the sale. Please call ahead for private lot viewing times. AUCTION SESSIONS Sunday, June 10, 2018 Session I, 10:00 A.M. Lots United States Coinage , Colonials to Dollars 1-730 United States Gold Coinage 731-769 United States Commemoratives 770-856 U.S. Patterns & Error Coinage 857-862 U.S. Proof Sets, Misc., Paper, Tokens & Medals 862-1018 Canadian Coinage 1019-1136 Ancient, Medieval & Islamic Coinage 1137-1219 Monday, June 11, 2018 Session II, 10:00 A.M. World Gold Coinage 1220-1326 World Crowns & Minor Coinage 1327-2356 World Miscellaneous 2357-2397 World Paper, Tokens & Medals 2398-2413 Session III, Immediately following Session II Collector’s Cabinet World Crowns & Minors 3001-3080 Presented by Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. P.O. Box 22026, Lansing, MI 48909 U.S.A. Tel: 517.394.4443; Fax: 517.394.0579 Website: www.numismaticauctionsllc.com Email: [email protected] Numismatic Auctions, LLC Auction Sale 62 - June 10-11, 2018 Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. Mailing Address: Tel: 517.394.4443; Fax: 517.394.0579 P.O. Box 22026 Email: [email protected] Lansing, MI 48909 U.S.A. -

How to Collect Coins a Fun, Useful, and Educational Guide to the Hobby

$4.95 Valuable Tips & Information! LITTLETON’S HOW TO CCOLLECTOLLECT CCOINSOINS ✓ Find the answers to the top 8 questions about coins! ✓ Are there any U.S. coin types you’ve never heard of? ✓ Learn about grading coins! ✓ Expand your coin collecting knowledge! ✓ Keep your coins in the best condition! ✓ Learn all about the different U.S. Mints and mint marks! WELCOME… Dear Collector, Coins reflect the culture and the times in which they were produced, and U.S. coins tell the story of America in a way that no other artifact can. Why? Because they have been used since the nation’s beginnings. Pathfinders and trendsetters – Benjamin Franklin, Robert E. Lee, Teddy Roosevelt, Marilyn Monroe – you, your parents and grandparents have all used coins. When you hold one in your hand, you’re holding a tangible link to the past. David M. Sundman, You can travel back to colonial America LCC President with a large cent, the Civil War with a two-cent piece, or to the beginning of America’s involvement in WWI with a Mercury dime. Every U.S. coin is an enduring legacy from our nation’s past! Have a plan for your collection When many collectors begin, they may want to collect everything, because all different coin types fascinate them. But, after gaining more knowledge and experience, they usually find that it’s good to have a plan and a focus for what they want to collect. Although there are various ways (pages 8 & 9 list a few), building a complete date and mint mark collection (such as Lincoln cents) is considered by many to be the ultimate achievement. -

PRECIOUS METALS LIST the Following Is a List of Precious Metals That Madison Trust Will Accept

PRECIOUS METALS LIST The following is a list of precious metals that Madison Trust will accept. TRUST COMPANY GOLD • American Eagle bullion and/or proof coins (except for “slabbed” coins) • American Buffalo bullion coins • Australian Kangaroo/Nugget bullion coins • Austrian Philharmonic bullion coins • British Britannia (.9999+ fineness) bullion coins • Canadian Maple Leaf bullion coins • Mexican Libertad bullion coins (.999+ fineness) • Bars, rounds and coins produced by a refiner/assayer/manufacturer accredited/certified by NYMEX/COMEX, NYSE/Liffe, LME, LBMA, LPPM, TOCOM, ISO 9000, or national government mint and meeting minimum fineness requirements(2)(3) SILVER • American Eagle bullion and/or proof coins (except for “slabbed” coins) • American America the Beautiful bullion coins • Australian Kookaburra and Koala bullion coins • Austrian Philharmonic bullion coins • British Britannia bullion coins • Canadian Maple Leaf bullion coins • Mexican Libertad bullion coins • Bars, rounds and coins produced by a refiner/assayer/manufacturer accredited/certified by NYMEX/COMEX, NYSE/Liffe, LME, LBMA, LPPM, TOCOM, ISO 9000, or national government mint and meeting minimum fineness requirements(2)(3) PLATINUM • American Eagle bullion and/or proof coins (except for “slabbed” coins) • Australian Koala bullion coins • Canadian Maple Leaf bullion coins • Bars, rounds and coins produced by a refiner/assayer/manufacturer accredited/certified by NYMEX/COMEX, NYSE/Liffe, LME, LBMA, LPPM, TOCOM, ISO 9000, or national government mint and meeting minimum -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

Modern Issues May 2021

MODERN ISSUES - MAY 2021 This Modern Issues list includes 3 Different lists People, Places, Maps & Travel - Plants & Animals - Sports PEOPLE, PLACES, MAPS & TRAVEL! GOLD, ETC. BELIZE 100 Dollars 1976 “Mayan Symbols” Matte - 239.00 FRANCE 5 Euro 2002 “Seed Sower” KM-1347 Silver Proof w/ Gold Insert – 290.00 GUYANA *100 Dollars 1976 “El Dorado” Proof – 187.00 ISRAEL Bar Mitzvah Medal ND 13mm 1.7 grams, 0.900 Fine Proof - 104.00 5 New Sheqalim 1988 "Caesarea" Proof - 554.00 SILVER, ETC. ANDORRA *Diner 1983 “D’Urgell I” Brass ChUnc – 11.00 ARAUCANIA-PATAGONIA 100 Pesos 1988 “Felipe” X#-21 C-N-Z Proof – 14.00 ARMENIA 25 Dram 1996 “Jesus” X#2c.1 Tri-Metal Reeded Edge Proof, Mtg: 100 – 60.00 100 Dram 1997 “Charents” C-N ChBU(2) – 2.00 ARUBA Casino Arusino 50 Guilder ND(1978)-FM "Dice Logo" 32mm Octagon Sterling Silver Proof - 11.00 AUSTRALIA 50 Cents 1970 “Cook-Map” C-N BU+(2) - 0.75 50 Cents 1970 "Cook-Map" C-N ChAU - 0.50 50 Cents 2000 “Milennium” C-N EF – 0.75 50 Cents 2008 “Year of the Scout” C-N ChBU in PNC – 3.00 *Dollar 1993 S “Landcare” A-B ChBU in Royal Easter Show folder – 3.25 *Dollar 1993-C “Landcare” A-B ChBU in Canberra Mint folder – 3.25 *Dollar 1993-M “Landcare” A-B ChBU in Royal Melbourne Show folder – 4.50 *Dollar 1996-C “Parkes” A-B ChBU – 3.25 *Dollar 1997 "Old Parliament House" Ounce Proof - 33.00 *Dollar 1999-C “Last Anzacs” A-B GemBU – 5.00 *Dollar 1999 “QEII-3 Portraits” KM-476 Ounce Proof, Mtg:16,829 – 54.00 *Dollar 2000 “Victoria Cross” A-B GemBU in RAM Wallet – 52.00 Dollar 2001-S “Army” N-A-C ChBU – 6.50 *Dollar 2002 -

Vida Cotidiana Durante La Revolución Mexicana Alejandro Rodriguez-Mayoral University of Texas at El Paso, Alejandro [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2015-01-01 Zapatistas: Vida cotidiana durante la Revolución Mexicana Alejandro Rodriguez-Mayoral University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Rodriguez-Mayoral, Alejandro, "Zapatistas: Vida cotidiana durante la Revolución Mexicana" (2015). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1138. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1138 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ZAPATISTAS: VIDA COTIDIANA DURANTE LA REVOLUCIÓN MEXICANA ALEJANDRO RODRIGUEZ-MAYORAL Departamento de Historia APROBADO: Samuel Brunk, Ph.D., Chair Yolanda Chávez Leyva, Ph.D. Sandra McGee Deutsch, Ph.D. Howard Campbell, Ph.D. Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © por Alejandro Rodriguez-Mayoral 2015 Dedicatoria Dedico esta disertación a Dios. ZAPATISTAS: VIDA COTIDIANA DURANTE LA REVOLUCIÓN MEXICANA por ALEJANDRO RODRIGUEZ-MAYORAL, Máster DISERTACIÓN Presentada a la facultad de la Escuela de Graduados de la Universidad de Texas en El Paso en cumplimiento parcial de los requerimientos para el Grado de DOCTOR Departamento de Historia UNIVERSIDAD DE TEXAS EN EL PASO Mayo 2015 AGRADECIMIENTOS Esta tesis doctoral fue escrita con el apoyo incondicional de amigos, familiares y profesores durante mi preparación académica, proceso de investigación y escritura de la misma. Deseo hacer presente mi gratitud a Servando Ortoll, Avital Bloch, Charles Ambler, Cheryl E. -

Precious Metals Investment Authorization

Toll Free: 800-962-4238 PacificPremierTrust.com Precious Metals Investment / Transfer Authorization IMPORTANT INFORMATION Sending incomplete documents will delay the funding/transfer process. Please make sure the Pacific Premier Trust Account (“Account”) contains sufficient cash to cover the investment, minimum cash requirement and all applicable transaction fees. Before closing: Depository Trust Company of Delaware, LLC provides precious metals safekeeping and shipping services as an independent contractor of Pacific Premier Trust. Depository Trust Company of Delaware, LLC is not affiliated with Pacific Premier Trust. PURCHASING/LIQUIDATING PRECIOUS METALS: Pacific Premier Trust is not a precious metals dealer. If you are interested in investing in precious metals within your IRA, you must utilize one from the list of precious metals’ dealer’s. If the metals dealer is not on the list, your request may be delayed or rejected. Once you have identified the dealer you would like to work with and you have negotiated a purchase with the dealer (metal type, weight, etc.) please submit this form to Pacific Premier rustT so we can forward the appropriate funds to complete the transaction. Please accompany this Pacific Premier Trust form with the selected metals dealer invoice for the purchase. At the time funds are transferred, Pacific Premier Trust will also forward shipping instructions to the dealer so the metals will be shipped and deposited into your newly established Depository Trust Company of Delaware account. Please be sure the amount listed on this form is inclusive of any dealer commission, shipping, handling and insurance costs. Pacific Premier Trust will pass through any costs associated with precious metals storage to your Account. -

Catálogo De Productos Numismáticos NUMISMATIC PRODUCTS CATALOGUE

catálogo de productos numismáticos NUMISMATIC PRODUCTS CATALOGUE METALES FINOS / PRECIOUS METALS 3 catálogo de productos numismáticos NUMISMATIC PRODUCTS CATALOGUE metales finos PRECIOUS METALS NUMISMÁTICA NUMISMATICS otros productos (AGOTADOS) OTHER PRODUCTS (SOLD OUT) FAMILIA DEL CENTENARIO METALES FINOS / PRECIOUS METALS 5 CENTENARIO FAMILY Centenario Azteca Hidalgo (50 pesos oro) (20 pesos oro) (10 pesos oro) M: Au A: BU M: Au A: BU M: Au A: BU P: 1.2057 Oz. L: 0.900 P: 0.4823 Oz. L: 0.900 P: 0.2411 Oz. L: 0.900 Ø: 37 mm Ø: 27.5 mm Ø: 22.5 mm 1/2 Hidalgo 1/4 Hidalgo 1/5 Hidalgo (5 pesos oro) (2.5 pesos oro) (2 pesos oro) M: Au A: BU M: Au A: BU M: Au A: BU P: 0.1206 Oz. L: 0.900 P: 0.0603 Oz. L: 0.900 P: 0.0482 Oz. L: 0.900 Ø: 19 mm Ø: 15.5 mm Ø: 13 mm serie libertad* LIBERTAD SERIES PLATA / SILVER Acabado espejo / Proof quality Acabado satín / Brilliant uncirculated quality Acabado mate-brillo / Proof-like quality LIBERTAD 2 Oz. Reverso común Anverso / Obverse M: Ag P: 5, 2, 1 Oz. 1998 Common reverse 5, 2, 1 Oz. L: 0.999 XX Conferencia Mundial de Directores M: Ag A: BU, PF de Casas de Moneda P: 5, 2, 1, 1/2, 1/4, 1/10, 1/20 Oz. XX Mint Directors Conference L: 0.999 Sudáfrica / South Africa Diámetros disponibles / Available Sizes Anverso / Obverse 1/2, 1/4, 1/10, 1/20 Oz. P: 5 Oz. -

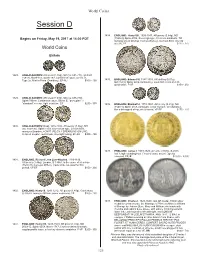

Auction 26 | September 15-17, 2016 | Session D

World Coins Session D Begins on Friday, September 16, 2016 at 14:00 PDT World Coins Europe (continued) 1232. GREAT BRITAIN: Commonwealth and Protectorate, 1649-1660, AR crown, 1658/7, KM-D207, Dav-3773, ESC-240, Spink-3226, Oliver Cromwell Protector issue, original Thomas Simon strike, a couple small reverse rim bumps, one-year type, VF, S $2,000 - 2,200 1227. GIBRALTAR: AE 2 quarts (9.08g), 1802, KM-Tn2.2, payable at R. Keeling, EF-AU $120 - 160 1233. GREAT BRITAIN: Commonwealth and Protectorate, 1649-1660, AE medal, 1658, Eimer-203, 38mm, death medal of Oliver Cromwell in silvered bronze, draped bust left with OLIVARIUS CROMWELL. around and I.DASSIER.F. at bottom / 1228. GIBRALTAR: AE quarto (4.41g), 1813, KM-Tn5, four genii tending monument with ANGLIAE. SCOL ET HIB. payable at Richard Cattons, Goldsmith, EF $120 - 160 PROTECTOR inscribed and NAT. 3. APRIL. 1603. MORT. 3. SEPT. 1658. in exergue, struck on cast planchet, part of Dassier’s Kings and Queens of England series, F-VF $75 - 100 1229. GIBRALTAR: AE 2 quartos (8.34g), 1820, KM-Tn9, payable at James Spittle’s, choice EF-AU $150 - 200 1234. GREAT BRITAIN: Charles II, 1660-1685, AR crown, 1662, KM-417.2, Dav-3774var, ESC-340, Spink-3350B, scarcer variety with striped cloak, central obverse a bit softly struck, old-time toning, VF $500 - 600 1230. GREAT BRITAIN: Elizabeth I, 1558-1603, AR shilling, S-2555, 2nd series, mintmark cross-crosslet (1560-61), VF $80 - 100 1235. GREAT BRITAIN: Anne, 1702-1714, AR ½ crown, 1745/3, KM-584.3, Spink-3695, LIMA under bust, F-VF $125 - 175 1231. -

Performing the Mexican Revolution in Neoliberal Times

ABSTRACT Since the time of the Mexican Revolution of 1910, images associated with this nation-defining event have been presented in an array of media and cultural productions. Within the past two decades these images have been re-imagined, re-coded and re/de- constructed in reaction to social and cultural changes associated with a crisis of political legitimation and the demise of hegemonic revolutionary ideology, as espoused by the long-ruling Party of the Institionalized Revolution (PRI), amid the generalized implementation of neoliberal policies in the county. My dissertation argues that the ascendance of neoliberalism, with the opening of Mexican economic and political systems, has resulted in changes in the socio-cultural work performed by the Revolution- Nation-Gender triad. This trinity, solidified in the post-Revolutionary national imaginary, weaves the three notions together such that as hegemonic discourses of Revolutionary nationalism enter in crisis, discourses of gender are also destabilized. The dissertation consists of three main sub-arguments. First, I argue that the discourse(s) surrounding Revolutionary heroes has been integral to the (re)definition of the Mexican nation and that analyzing recodings of this discourse through the example of Emiliano Zapata reveals a destabilization of hegemonic nationalism. These changes have allowed alternatives to surface both in Mexico and across the border as part of a recoded ii transnational Revolutionary nationalism. As cracks opened in the Revolutionary edifice allowing alternatives to emerge, they have also opened space for alternative gender discourses. I next argue that a close analysis of representations of masculine gender roles as manifested in a variety of cultural texts, specifically through Revolutionary icons Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, reveals a crisis of the macho archetype in the contemporary Mexican nation. -

The Colors and Shadows of My Word(S)

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Master's Theses 2000 The Colors and Shadows of My Word(s) Lydia A. Saravia University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses Recommended Citation Saravia, Lydia A., "The Colors and Shadows of My Word(s)" (2000). Open Access Master's Theses. Paper 1812. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses/1812 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. c,275 5325 At-\ 2000 THE COLORS AND SHADOWS OF MY WORD(S) BY LYDIA A. SARA VIA A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2000 1F L/5 t-19L-/05L/ Abstract If I find my voice, I will find my identity. Voice gives identity meaning. The acquisition of language (voice) means an acquisition of subjectivity (identity). A search for an identity is a search for voice. But formation of identity is difficult when multiple layers of subjectivity are to be considered: the layer of dual culture, in this case Guatemala and the United States, the layer of an urban environment, the layer of a working-class status, the layer of being female, which are all major players in the development of voice. To make sense of, and find a voice for, a fragmented identity is difficult. -

Auc28sesdweb.Pdf

World Coins Session D 1434. ENGLAND: Henry VIII, 1509-1547, AR penny (0.64g), ND Begins on Friday, May 19, 2017 at 14:00 PDT [1526-9], Spink-2352, Sovereign type, Crescent mintmark, TW flanking shield (Bishop Thomas Wolsey), Durham Mint, tiny clip at 7:00, VF $125 - 175 World Coins Britain 1428. ANGLO-SAXONS: AR sceat (1.16g), ND (ca. 695-715), Metcalf 158-70, North-163, Spink-792, Continental issue, Series D, Type 2c, Mint in Frisia (Domberg), EF-AU $100 - 150 1435. ENGLAND: Edward VI, 1547-1553, AR shilling (6.01g), ND [1551], Spink-2482, mintmark y, small flan crack at 2:30, good strike, F-VF $350 - 450 1429. ANGLO-SAXONS: AR sceat (1.04g), ND (ca. 695-740), Spink-790var, Continental issue, Series E, “porcupine” // “standard” reverse, light oxidation, EF $250 - 350 1436. ENGLAND: Elizabeth I, 1558-1603, AR penny (0.41g), ND [1560-1], Spink-2558, mintmark: cross-crosslet, second issue, flan a bit ragged at top, nicely toned, VF-EF $175 - 225 1430. ANGLO-SAXONS: Cnut, 1016-1035, AR penny (1.06g), ND (ca. 1029-36), Spink-1159, short cross type, Lincoln Mint, moneyer Swartinc, +CNVT .RE:CX // SPEARLINC ON LINC, lis tip on scepter, well struck, nice light toning, EF-AU $300 - 400 1437. ENGLAND: James I, 1603-1625, AV unite (9.63g), S-2618, half-length standing bust // coat of arms, mount expertly removed, EF, R $2,600 - 3,000 1431. ENGLAND: Richard I, the Lion-Hearted, 1189-1199, AR penny (1.44g), London, S-1348A, in the name of Henricus (Henry II), moneyer Willem, crude strike as usual for this period, VF-EF $150 - 200 1432.