MOLECULAR EVOLUTION, ADAPTIVE RADIATION, and GEOGRAPHIC DIVERSIFICATION in the AMPHIATLANTIC FAMILY RAPATEACEAE: EVIDENCE from Ndhf SEQUENCES and MORPHOLOGY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

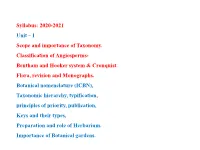

I Scope and Importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker System & Cronquist

Syllabus: 2020-2021 Unit – I Scope and importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker system & Cronquist. Flora, revision and Monographs. Botanical nomenclature (ICBN), Taxonomic hierarchy, typification, principles of priority, publication, Keys and their types, Preparation and role of Herbarium. Importance of Botanical gardens. PLANT KINGDOM Amongst plants nearly 15,000 species belong to Mosses and Liverworts, 12,700 Ferns and their allies, 1,079 Gymnosperms and 295,383 Angiosperms (belonging to about 485 families and 13,372 genera), considered to be the most recent and vigorous group of plants that have occurred on earth. Angiosperms occupy the majority of the terrestrial space on earth, and are the major components of the world‘s vegetation. Brazil (First) and Colombia (second), both located in the tropics considered to be countries with the most diverse angiosperms floras China (Third) even though the main part of her land is not located in the tropics, the number of angiosperms still occupies the third place in the world. In INDIA there are about 18042 species of flowering plants approximately 320 families, 40 genera and 30,000 species. IUCN Red list Categories: EX –Extinct; EW- Extinct in the Wild-Threatened; CR -Critically Endangered; VU- Vulnerable Angiosperm (Flowering Plants) SPECIES RICHNESS AROUND THE WORLD PLANT CLASSIFICATION Historia Plantarum - the earliest surviving treatise on plants in which Theophrastus listed the names of over 500 plant species. Artificial system of Classification Theophrastus attempted common groupings of folklore combined with growth form such as ( Tree Shrub; Undershrub); or Herb. Or (Annual and Biennials plants) or (Cyme and Raceme inflorescences) or (Archichlamydeae and Meta chlamydeae) or (Upper or Lower ovarian ). -

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

Arthur Monrad Johnson Colletion of Botanical Drawings

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7489r5rb No online items Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings 1914-1941 Processed by Pat L. Walter. Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division History and Special Collections Division UCLA 12-077 Center for Health Sciences Box 951798 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1798 Phone: 310/825-6940 Fax: 310/825-0465 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/biomed/his/ ©2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion 48 1 of botanical drawings 1914-1941 Descriptive Summary Title: Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings, Date (inclusive): 1914-1941 Collection number: 48 Creator: Johnson, Arthur Monrad 1878-1943 Extent: 3 boxes (2.5 linear feet) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division Los Angeles, California 90095-1490 Abstract: Approximately 1000 botanical drawings, most in pen and black ink on paper, of the structural parts of angiosperms and some gymnosperms, by Arthur Monrad Johnson. Many of the illustrations have been published in the author's scientific publications, such as his "Taxonomy of the Flowering Plants" and articles on the genus Saxifraga. Dr. Johnson was both a respected botanist and an accomplished artist beyond his botanical subjects. Physical location: Collection stored off-site (Southern Regional Library Facility): Advance notice required for access. Language of Material: Collection materials in English Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings (Manuscript collection 48). Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division, University of California, Los Angeles. -

Gondwanan Origin of Major Monocot Groups Inferred from Dispersal-Vicariance Analysis Kåre Bremer Uppsala University

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 22 | Issue 1 Article 3 2006 Gondwanan Origin of Major Monocot Groups Inferred from Dispersal-Vicariance Analysis Kåre Bremer Uppsala University Thomas Janssen Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Bremer, Kåre and Janssen, Thomas (2006) "Gondwanan Origin of Major Monocot Groups Inferred from Dispersal-Vicariance Analysis," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 22: Iss. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol22/iss1/3 Aliso 22, pp. 22-27 © 2006, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden GONDWANAN ORIGIN OF MAJOR MONO COT GROUPS INFERRED FROM DISPERSAL-VICARIANCE ANALYSIS KARE BREMERl.3 AND THOMAS JANSSEN2 lDepartment of Systematic Botany, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Norbyvagen l8D, SE-752 36 Uppsala, Sweden; 2Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Departement de Systematique et Evolution, USM 0602: Taxonomie et collections, 16 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France 3Corresponding author ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Historical biogeography of major monocot groups was investigated by biogeographical analysis of a dated phylogeny including 79 of the 81 monocot families using the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group II (APG II) classification. Five major areas were used to describe the family distributions: Eurasia, North America, South America, Africa including Madagascar, and Australasia including New Guinea, New Caledonia, and New Zealand. In order to investigate the possible correspondence with continental breakup, the tree with its terminal distributions was fitted to the geological area cladogram «Eurasia, North America), (Africa, (South America, Australasia») and to alternative area cladograms using the TreeFitter program. -

Diversity and Evolution of Monocots

Commelinids 4 main groups: Diversity and Evolution • Acorales - sister to all monocots • Alismatids of Monocots – inc. Aroids - jack in the pulpit • Lilioids (lilies, orchids, yams) – non-monophyletic . spiderworts, bananas, pineapples . – petaloid • Commelinids – Arecales – palms – Commelinales – spiderwort – Zingiberales –banana – Poales – pineapple – grasses & sedges Commelinids Commelinales + Zingiberales • theme: reduction of flower, loss of nectar, loss of zoophily, evolution of • 2 closely related tropical orders bracts • primarily nectar bearing but with losses • bracted inflorescences grass pickeral weed pickeral weed spiderwort heliconia nectar pollen only bracts rapatead bromeliad Commelinaceae - spiderwort Commelinaceae - spiderwort Family of small herbs with succulent stems, stems jointed; leaves sheathing. Family does not produce Inflorescence often bracted nectar, but showy flowers for insect pollen gathering. Rhoeo - Moses in a cradle Commelina erecta - Erect dayflower Tradescantia ohiensis - spiderwort Tradescantia ohiensis - spiderwort Commelinaceae - spiderwort Commelinaceae - spiderwort Flowers actinomorphic or • species rich in pantropics, CA 3 CO 3 A 6 G (3) zygomorphic especially Africa • floral diversity is enormous Commelina communis - day flower Tradescantia ohiensis - spiderwort Pontederiaceae - pickerel weed Pontederiaceae - pickerel weed Aquatic family of emergents or floaters. Pickerel weed has glossy heart-shaped leaves, Water hyacinth (Eichhornia) from superficially like Sagittaria but without net venation. -

Evolutionary History of Floral Key Innovations in Angiosperms Elisabeth Reyes

Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms Elisabeth Reyes To cite this version: Elisabeth Reyes. Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms. Botanics. Université Paris Saclay (COmUE), 2016. English. NNT : 2016SACLS489. tel-01443353 HAL Id: tel-01443353 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01443353 Submitted on 23 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. NNT : 2016SACLS489 THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PARIS-SACLAY, préparée à l’Université Paris-Sud ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 567 Sciences du Végétal : du Gène à l’Ecosystème Spécialité de Doctorat : Biologie Par Mme Elisabeth Reyes Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms Thèse présentée et soutenue à Orsay, le 13 décembre 2016 : Composition du Jury : M. Ronse de Craene, Louis Directeur de recherche aux Jardins Rapporteur Botaniques Royaux d’Édimbourg M. Forest, Félix Directeur de recherche aux Jardins Rapporteur Botaniques Royaux de Kew Mme. Damerval, Catherine Directrice de recherche au Moulon Président du jury M. Lowry, Porter Curateur en chef aux Jardins Examinateur Botaniques du Missouri M. Haevermans, Thomas Maître de conférences au MNHN Examinateur Mme. Nadot, Sophie Professeur à l’Université Paris-Sud Directeur de thèse M. -

GENOME EVOLUTION in MONOCOTS a Dissertation

GENOME EVOLUTION IN MONOCOTS A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Kate L. Hertweck Dr. J. Chris Pires, Dissertation Advisor JULY 2011 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled GENOME EVOLUTION IN MONOCOTS Presented by Kate L. Hertweck A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. J. Chris Pires Dr. Lori Eggert Dr. Candace Galen Dr. Rose‐Marie Muzika ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for their assistance during the course of my graduate education. I would not have derived such a keen understanding of the learning process without the tutelage of Dr. Sandi Abell. Members of the Pires lab provided prolific support in improving lab techniques, computational analysis, greenhouse maintenance, and writing support. Team Monocot, including Dr. Mike Kinney, Dr. Roxi Steele, and Erica Wheeler were particularly helpful, but other lab members working on Brassicaceae (Dr. Zhiyong Xiong, Dr. Maqsood Rehman, Pat Edger, Tatiana Arias, Dustin Mayfield) all provided vital support as well. I am also grateful for the support of a high school student, Cady Anderson, and an undergraduate, Tori Docktor, for their assistance in laboratory procedures. Many people, scientist and otherwise, helped with field collections: Dr. Travis Columbus, Hester Bell, Doug and Judy McGoon, Julie Ketner, Katy Klymus, and William Alexander. Many thanks to Barb Sonderman for taking care of my greenhouse collection of many odd plants brought back from the field. -

Pollen Morphology of Rapateaceae Sherwin Carlquist Claremont Graduate School

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 5 | Issue 1 Article 7 1961 Pollen Morphology of Rapateaceae Sherwin Carlquist Claremont Graduate School Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Carlquist, Sherwin (1961) "Pollen Morphology of Rapateaceae," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 5: Iss. 1, Article 7. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol5/iss1/7 ALISO VoL. 5, No. 1, pp. 39-66 MAY 15, 1961 POLLEN MORPHOLOGY OF RAPATEACEAE SHERWIN CARLQUIST1 Claremont Graduate School, Claremont, California INTRODUCTION Several circumstances prompt the presentation of studies on pollen morphology of Rapa teaceae at this time. First, recent explorations in the Guayana Highland region of northern South America have amassed excellent collections in this interesting monocotyledonous family. The family is restricted to South America with the exception of a monotypic genus in western tropical Africa (Maguire et al., 1958). Although there is no reason to believe that all new species in the family have been described, the remarkable collections of material certainly do furnish an extensive basis for pollen study which has not been available previ ously. Of great significance in this regard are the collections of Maguire and his associates at the New York Botanical Garden. Many of these collections included liquid-preserved portions. A second reason for presentation of pollen studies is the excellent condition in which pollen-bearing material of many species was preserved. Because the delicate nature of pollen grains of Rapateaceae, as described below, makes preparation of pollen-grain slides from dried material often unsatisfactory, liquid-preserved material is especially im portant. -

Floral Anatomy and Development of Saxofridericia Aculeata (Rapateaceae) and Its Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Significance Author(S): Renata C

Floral anatomy and development of Saxofridericia aculeata (Rapateaceae) and its taxonomic and phylogenetic significance Author(s): Renata C. Ferrari and Aline Oriani Source: Plant Systematics and Evolution, Vol. 303, No. 2 (February 2017), pp. 187-201 Published by: Springer Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44854166 Accessed: 21-06-2021 11:49 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Plant Systematics and Evolution This content downloaded from 86.59.13.237 on Mon, 21 Jun 2021 11:49:29 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Plant Syst Evol (2017) 303:187-201 f CrossMark DOI 10.1 007/s00606-0 1 6- 1 36 1 -z ORIGINAL ARTICLE Floral anatomy and development of Saxofridericia aculeata (Rapateaceae) and its taxonomie and phylogenetic significance Renata C. Ferrari1©* Aline Oriani1 Received: 9 May 201 6 /Accepted: 13 October 2016 /Published online: 28 October 2016 © Springer- Verlag Wien 2016 Abstract Floral anatomy and development Keywordsof Saxofrid- Cluster analysis • Colleter • Monotremoideae • ericia aculeata Körn was studied in a comparative Postgenital intercarpellary fusion • Rapateoideae • approach to contribute to the understanding of the family. -

The Fossil Record of Angiosperm Families in Relation to Baraminology

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 7 Article 31 2013 The Fossil Record of Angiosperm Families in Relation to Baraminology Roger W. Sanders Bryan College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Sanders, Roger W. (2013) "The Fossil Record of Angiosperm Families in Relation to Baraminology," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 7 , Article 31. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol7/iss1/31 Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Creationism. Pittsburgh, PA: Creation Science Fellowship THE FOSSIL RECORD OF ANGIOSPERM FAMILIES IN RELATION TO BARAMINOLOGY Roger W. Sanders, Ph.D., Bryan College #7802, 721 Bryan Drive, Dayton, TN 37321 USA KEYWORDS: Angiosperms, flowering plants, fossils, baramins, Flood, post-Flood continuity criterion, continuous fossil record ABSTRACT To help estimate the number and boundaries of created kinds (i.e., baramins) of flowering plants, the fossil record has been analyzed. To designate the status of baramin, a criterion is applied that tests whether some but not all of a group’s hierarchically immediate subgroups have a fossil record back to the Flood (accepted here as near the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary). -

Novelties in Rapatea (Rapateaceae) from Colombia Gerardo A

Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. Ex. Fis. Nat. 40(157):644-652, octubre-diciembre de 2016 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.18257/raccefyn.403 Artículo original Ciencias Naturales Novelties in Rapatea (Rapateaceae) from Colombia Gerardo A. Aymard C.1,2,*, Henry Arellano-Peña1,3 1Compensation International Progress S. A. –Ciprogress Greenlife– , Bogotá, Colombia 2UNELLEZ-Guanare, Programa de Ciencias del Agro y el Mar, Herbario Universitario (PORT), Mesa de Cavacas, Estado Portuguesa, Venezuela 3Grupo de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Conservación, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales,Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia Abstract Rapatea isanae, from the upper Isana [Içana] river, Guianía Department, Colombia, is described and illustrated, and its morphological relationships with allied species are discussed. This taxon is remarkable for Rapatea in its small stature (15–30 cm tall) and leaves, and it is only the second species with white petals in a genus that otherwise has only yellow petals. It is most closely R. spruceana, with the base of the leaf blade gradually tapering from the intergrading into the petiole, and the bractlet of the spikelet and sepal shape. However, this new species differs from R. spruceana in its shorter size, sparse verrucose on the lower surface, the length of the attenuate portion of the involucral bracts, and the shape and color of the petals. It also has similarities to R. longipes and R. modesta in its ventricose sheath-leaf, inflorescence shape, and bractlets equal in length. A previously described species from Colombia is restablished (i.e., R. modesta), and one variety is elevated to the rank of species (i.e., R. -

A Critique of "Bromeliales, Related Monocots, and Resolution of Relationships Among Bromeliaceae Subfamilies" Source: Systematic Botany, Vol

A Critique of "Bromeliales, Related Monocots, and Resolution of Relationships among Bromeliaceae Subfamilies" Source: Systematic Botany, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 1988), pp. 610-619 Published by: American Society of Plant Taxonomists Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2419205 Accessed: 06-04-2016 16:20 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Society of Plant Taxonomists is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Systematic Botany This content downloaded from 130.191.17.38 on Wed, 06 Apr 2016 16:20:32 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Systematic Botany (1988), 13(4): pp. 610-619 ? Copyright 1988 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists Commentaries A Critique of "Bromeliales, Related Monocots, and (length = 23) and has the highest consistency index Resolution of Relationships among Bromeliaceae (C.I. = 0.957) is that seen in figure lb, in which out- Subfamilies." In a recent article by Gilmartin and group X is analyzed alone with the ingroup. In con- Brown (1987), the interrelationships of the three de- trast, the trees of figure lc and ld are both longer and fined subfamilies of the Bromeliaceae were studied have lower consistency indices.